“Wouldn’t You Like To Help Debbie Smile Again?”

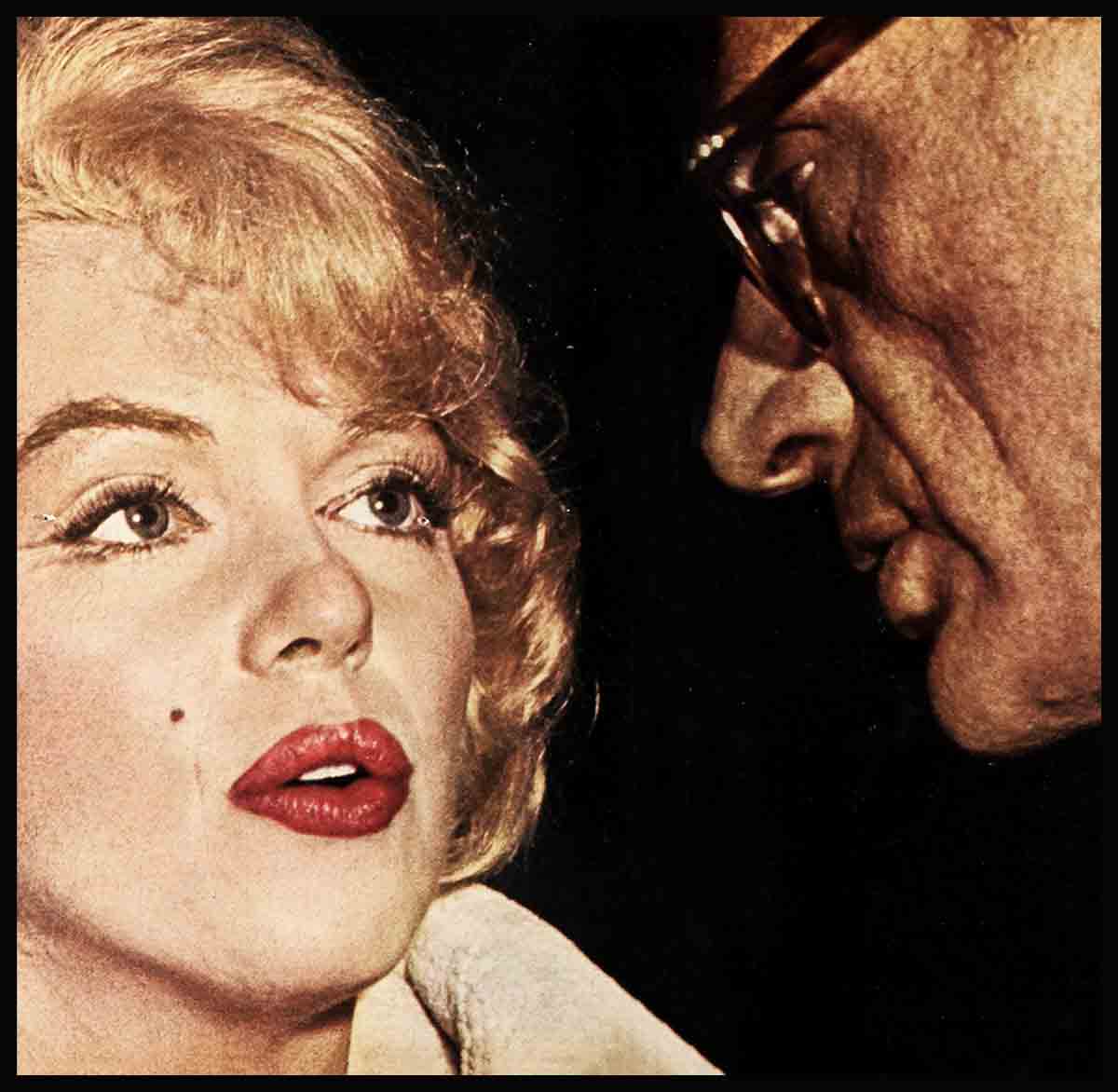

Susie saw the pretty lady sitting there, so golden and smiling.

She stopped and said, “Would you like to come and see how I can draw?” That’s how it began.

“I’m Susie,” she says. “Who are you?” I’m Debbie, Susie.” The child asks her gravely, “Do you want to see my clinic?”

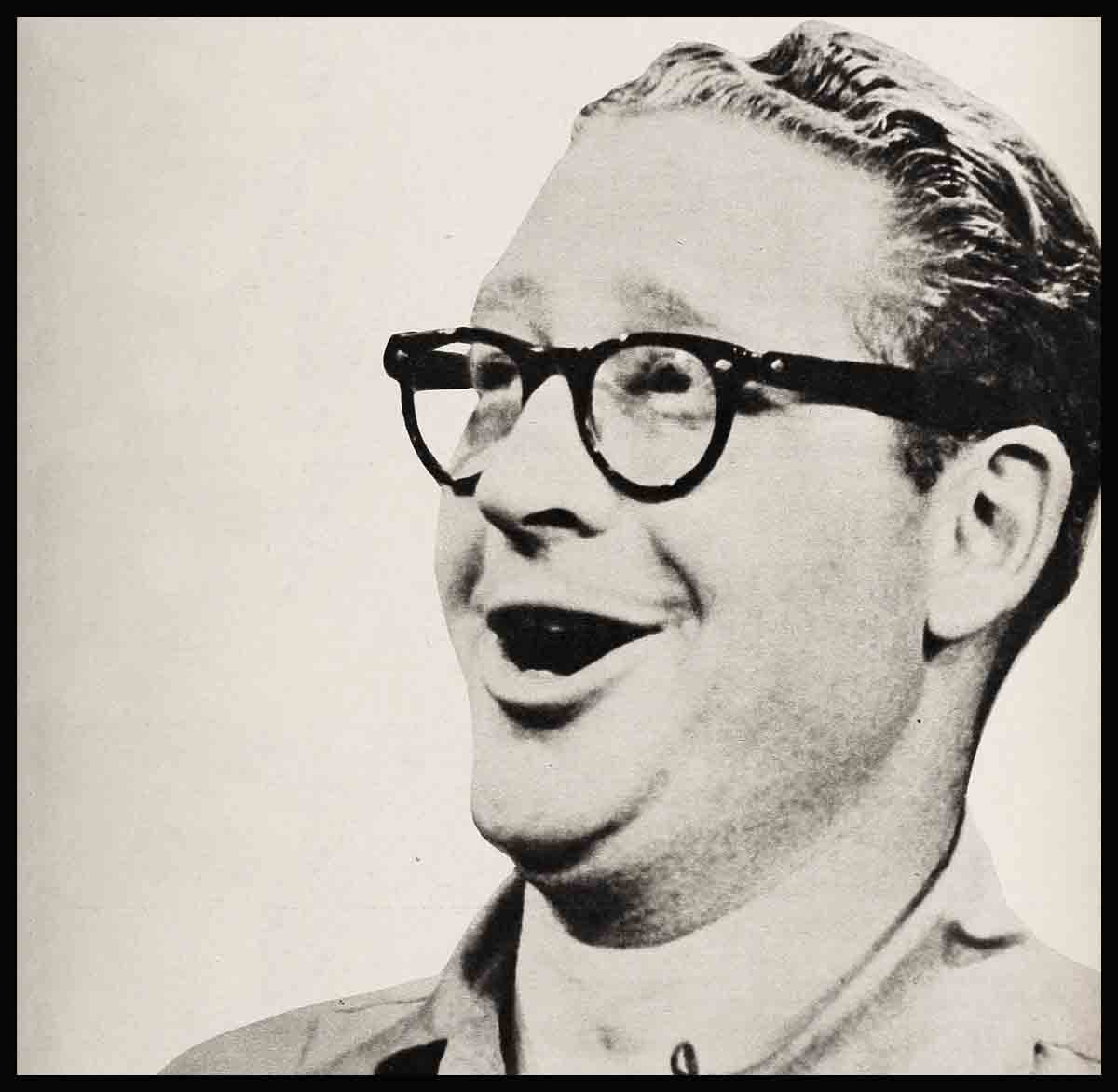

“Really all yours?” “Mostly.” The visitor smiles. She knows about this six-year-old Susie from Dr. Louis Wise, who directs the Thalians Clinic here at Mount Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles. She knows that Susie’s mother is probably inside with her caseworker. Susie should be playing in the therapy room. She asks her, ’ Are you supposed to be playing in the therapy room, Susie?”

Susie nods yes. Then says, “Come,” and confidingly puts her hand in Debbie’s as they walk down the spanking-clean corridor. She opens a door and leads Debbie through it.

“This is my therapy room,” Susie tells the pretty visitor. “I have a blackboard Look what I drew.” And Debbie is thrilled at the big drawings, because when Susie first came to the clinic all her drawings were tiny and tight and all jammed onto the edge of the board.

“Tell me about the drawing, Susie. What a nice house,” Debbie says.

“Well, that’s this girl’s house and the smoke is coming out in loops and loops because the wind blows it.”

AUDIO BOOK

“Susie, that’s good. I can see the wind.”

“And here is the girl, big, a very big girl like me.”

But Susie has had enough of the blackboard for now.

“Come,” she pleads, “come in this room with me.” Debbie follows and finds herself face to face with Dr. Wise and Bob Anderson, the phychiatric caseworker. Debbie knows them both very well, but she lets Susie introduce her to them.

“This is my friend Debbie,” Susie tells them, and each of the men answers politely, “How do you do, Debbie.” They all sit down at an enormous conference table—so big that Susie looks quite tiny leaning against the very edge of it. Tiny and big-eyed and serious.

“They talk a lot,” she tells Debbie.

“They have a lot to talk about, and so have we,” Debbie says. “Because some day we want a building six-stories tall, so many, many children can come here.”

“I’m in first grade, A-1, and today we read a story about a monkey.” Suddenly Susie confides, “I used to dream a monkey and a gorilla chased me.”

“My little girl and boy saw some monkeys at the circus,” Debbie confides right back.

“What’s her name?”

“Carrie.”

“Mine’s Susie.”

“Mine’s Debbie.”

“I know, you told me.”

“Well then you tell me something, Susie Tell me the name of this beautiful big place.”

“I’ll show you,” Susie says and promptly takes Debbie’s hand and with a goodbye wave to the doctor she leads Debbie out and down the long corridor, out to the entranceway. She points to a plaque set into one wall. “I can’t read big words,” she says, “but you may read them to me if you like.”

Debbie reads out loud, “The Thalians Clinic For Children, Mount Sinai Hospital.” But she does not tell Susie that she is the president of the Thalians, which is a group of young people in Hollywood who dedicate themselves to helping emotionally disturbed children. And she doesn’t tell Susie that last year, alone, the Thalians raised more than $85,000 for these little children, like Susie, who have problems too big for their mommies and daddies to tackle all by themselves. She just takes the trustful hand offered her, and they go back to the therapy room to play some more.

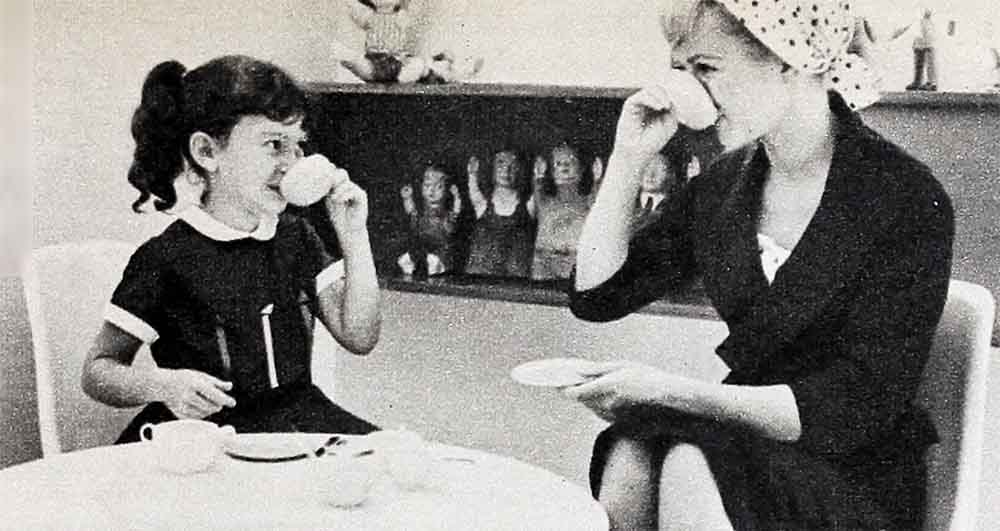

“Let’s play tea party,” Susie says. She gets the plastic dishes off the shelf and arranges them, handing a cup to Debbie.

“Thank you,” Debbie says. “Mmm, mmm.”

“Mmm Mmm,” Susie says.

“May I have cream, please, Susie?”

Susie pours it.

“And sugar? Two lumps, please?”

“I take two lumps, too. I like to eat them without the tea,” Susie says. “Okay. Down the hatch.”

Debbie giggles and when Susie wants to know why, she explains that “down the hatch” is a comical thing for a little girl to say.

“I’m a big girl,” Susie insists. She runs and letches a ruler. “Measure me and see how big I am.”

You are a big girl, Susie. What are you going to be when you grow up?”

“An ice skater. Did you ever see ice skaters on TV?”

“Hold still, Susie.”

“How tall am I?”

“Forty-eight.”

“Pounds?”

“Inches, Susie.” Debbie explains carefully. “Pounds is how much you weigh.”

“I eat a lot. My daddy used to say, ‘Eat Susie, eat, Susie.’ But I didn’t. Now I eat. Spaghetti is what I like best. You know, the one that’s on TV.”

Suddenly she runs over to a shelf.

“These are my puppets,” she tells Debbie. “Mama and Daddy and baby puppet. You can hold the baby one.”

“Hi, Mommy,” Debbie says, making her voice sound like the baby puppet. “What does the mommy say?”

“She says ‘kiss.’ ” She kisses the baby.

“Good,” says Debbie, “that’s what babies like.” Then in her baby voice, “Hi, Daddy. Hold my hand, Daddy.”

“The daddy kisses the baby, too,” says Susie.

“Can we go to the park, Mommy?” says Debbie’s baby.

“Yes,” Susie says. “You’ve been a pretty good baby today. You didn’t mess all your diapers. I’ll take you to the park.”

After that, Susie decides she’d like to be read to.

Debbie takes out a book of Carrie’s she’s had in her big purse. “Carrie, my little girl, left this in the car. It’s called ‘The Happy Apple.’ And here is a little fur dog of my Todd’s.”

“Read,” says Susie, snuggling contentedly against her and cuddling the fur dog.

“Here’s an apple, red and round,” reads Debbie, “lying on the grassy ground. Two big tears fall from his eyes. I wonder why the apple cries?”

“He’s angry,” Susie says very definitely. “But he doesn’t have to be.”

Debbie keeps reading aloud.

“The whole day long on grass I lie, just staring at the bright blue sky. . . .’’

“I go to school. I don’t look at the sky in school, only at recess. I listen to the teacher and we read. I can read almost as good as Sara Jane and Timmy.”

This is very good news, but it’s time for Debbie to go now. At the last minute, Susie remembers one more thing—the animals. She takes Debbie to the room next to the office and shows her the big, fat bear, the lazy lion, the pup and the elephants. They’re all on display because the Thalians sell them to raise extra money for the clinic. They’re gay and comical animals, but Susie looks at them in her own sober, serious way.

“Oh, Susie, look at those funny elephants!” Debbie enthuses. “Let’s be elephants. Put up your trunk and be an elephant!” Debbie shows her how.

“Do elephants bark?” Susie says.

“Honk, honk,” Debbie says.

And Susie bursts out laughing!

Debbie laughs with her—for sheer pleasure. Because this was a little girl who, when asked to read in school, used to burst into tears. She was so shy, she wouldn’t go to a playmate’s birthday party unless her mother agreed to stay with her. When she was able to control her tears and answer a question in class, she stuttered pitifully. She looked stupid, but her teacher had a feeling she was not. The school nurse had the same feeling, and so did the principal. He talked to the child’s mother.

Susie’s mother certainly did not think hers was an emotionally disturbed child. But when the family physician went along with the principal, the mother went along with both of them. She was anxious to do anything that would help Susie become a happy, friendly, outgoing little girl.

Susie’s problems were brought to the attention of the Thalians Clinic. There’s a waiting list there, but after Susie had been interviewed by a psychiatrist and it was obvious that there was no brain damage, that her case was highly treatable and the need great, she was not made to wait.

For six months, now, Susie has spent an hour twice a week with her psychiatrist, a calm, strong man who neither pushes nor probes. She is free to play with the toys in the therapy room, and to talk with her therapist. Gradually he has explained many things to Susie. She has come to feel at home here, accepted; she’s begun to understand her problems and her parents’ problems. Where her drawings at first were vague attempts, small, tight, withdrawn little things at the corner of the page or blackboard, she is drawing quite normally and bravely now, right out in the middle—and using vivid colors rather than somber ones.

What psychiatrists and caseworkers have learned through examining the parents and child and comparing notes: Susie has been a confused little girl because of the attitudes of her parents. Her mother is an aggressive woman who wants Susie to become everything she herself wanted to be but also, unconsciously, links Susie with a younger sister who was her bitter rival in childhood. Susie sensed this hostility in her mother, tried desperately to please her but never reached the mark set for attainment and, therefore, had become afraid to even try. She turned for comfort to her daddy; but this man, who holds down a perfectly good job in electronics, sheds his masculinity when he walks in the door of his home. He hasn’t been able to stand up to his aggressive wife, or to be the man she demands him to be. Instead, he is inclined to lean on her.

He’s wanted to pet and comfort Susie but then the mother would turn on them both with her sharp critical tongue: “Don’t baby her, Luke. Let her learn to stand on her own two feet. It’s more than you’ve ever done!” The man restrains his temper and retreats into his own misery. Susie would step toward him, then step away befuddled. She never knew which one she ought to be like. Mother wanted her to be strong but slapped her if she acted like a tomboy. But when she went to the other extreme and became what Daddy wanted—the feminine correct little girl—her mother carped about being too soft, too vulnerable, too trusting! “Don’t trust people. Don’t trust men.”

“Don’t stutter, baby,” her father’d say. “You’re not a baby.”

Any wonder Susie stuttered? Any wonder Susie cried? Whatever she did, she was wrong. Debbie became fascinated with the case history and when she saw Susie this particular day, she found her still shy but certainly emerging. First of all, Susie’s mother has gradually become aware of how unfair she’s been to the child, aware that her hostility is a holdover from her own childhood when she felt her parents loved her younger sister more than they did her. She’s accepted suggestions on how to involve herself with Susie; of how, for example, to help fix her hair instead of, “Susie, you’re so dumb. I’ve told you ten times. . . .” She’s learned to give a word of encouragement—to her husband and to Susie. As the little girl feels her mother soften and letting go, as the harsh criticism drops off and she isn’t being pushed, she’s beginning to express herself. She can tell the therapist, “My mother and daddy are getting along better now.” And he can explain to her that the disagreements they used to have was the reason for the frightening nightmares she’d had when monkeys and gorillas chased and hurt her.

Susie likes the therapist. He’s very interested in everything she does and says. She feels important for the first time in her life. She’s not so afraid. With Debbie, she was at ease. Debbie’s gentle voice, her understanding of children, her warm smile and quiet manner drew Susie to her.

And when, at last, Debbie had to go home, Susie walked with her hand in hand all the way down the long, shiny corridor to the front door.

“Will you come and visit again?” Susie asked.

“I’ll come and visit,” Debbie promised. She knelt down, put both her arms around the little girl and gave her a close, warm hug. And Susie didn’t pull away the least bit—but she didn’t smile goodbye at Debbie, either.

“Won’t you give me a smile, Susie?” Debbie asked gently. But Susie just shook her head.

“I don’t feel like smiling,” she said.

“Oh, that’s all right,” Debbie said. And then, “Susie, I know what—just say ‘cheese.’ Like this, see?” Debbie said “cheese” and Susie said “cheese” exactly the same way—and they were both smiling.

“Oh that’s lovely, Susie,” Debbie cried. “That made the prettiest smile!”

The best part of it was, Susie smiled again without having to say “cheese” first. She didn’t know that movie stars like Debbie Reynolds can make “cheese” curve your lips up into a big, beautiful smile. She didn’t even know that her new friend, the very pretty lady, was Debbie Reynolds. And she certainly couldn’t know that when Debbie paid a visit to the clinic she might arrive somewhat saddened by her own personal problems, but always the sight of children getting better in “her clinic” made her proud and happy. She and the Thalians helped youngsters to smile, yes—but they did the same thing for her. Only Susie couldn’t know all this. At six and a half you can’t know everything.

—JANE ARDMORE

See Debbie in Paramount’s “Pleasure of His Company.” Watch for her in “Pepe” for Columbia and “Champagne Complex” for 20th Century-Fox. She sings on Dot.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1961

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments