Millie Perkins Reveals: “Why I Keep My True Love A Secret?”

To find the truth, we talked with many young girls in Hollywood . . . On the next eight pages are the revealing cases of four of these girls: one who is forced to keep her love a secret; one who frankly admits her romance was a fake; one whose engagement is becoming a Hollywood hassle; one whose romance was ruined by publicity. . . .

“Flowers!” the messenger boy called out. “Flowers for Miss Perkins—” On the busy set, noise came to a sudden stop. George Stevens, the director, looked up from the script he was studying. Shelley Winters dropped her comb and ran over. Nina Foch, Millie Perkins’ dramatic coach, stopped talking—with her mouth still open.

Every head turned to watch Millie Perkins dash across the floor.

Because after all, who would be sending Millie flowers? Little Millie Perkins who never went out, who didn’t know a soul in Hollywood, who looked so young that strangers talked to her as if she were a child—who on earth would be sending her flowers?

Breathless, Millie snatched the long green box out of the boy’s hands. Shelley Winters, standing over her, noticed that Millie’s hands were trembling. The next instant she wasn’t looking at Millie’s hands—she was gasping with surprise and staring down at the flowers.

For they were the loveliest she had ever seen. Long-stemmed roses, snowy white, nestled among green leaves with dew still trembling on them.

“Why, honey,” Shelley breathed, “who sent you those?”

Flowers from no one

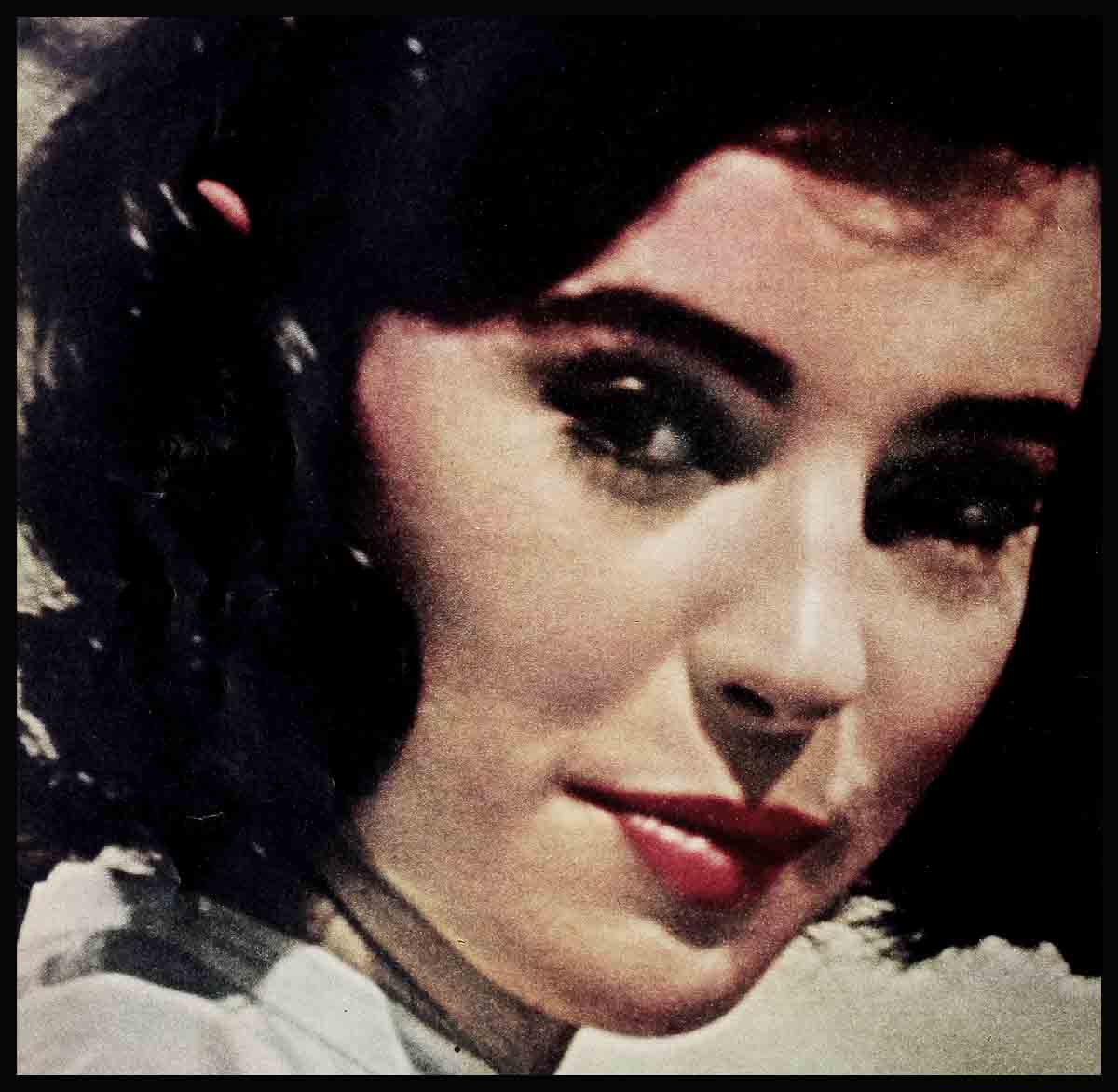

Millie Perkins looked up, her incredible thick black eyelashes making shadows on her cheeks. Her face was flushed, her lips smiled, her eyes shone.

“They—why, they’re from—” Suddenly her voice faded away. She took a quick look around the set. George Stevens was smiling at her. Across the room a carpenter caught her eye and self-consciously turned back to his work. The glow faded from Millie’s face. The smile disappeared.

“I don’t know,” she said faintly, in the voice she used when reporters’ questions shocked her into shyness.

Shelley stared at her. “You don’t know?”

Millie’s lashes dropped. Now her face turned red. Her voice was fainter than ever. “That’s right. See—there’s no card.”

Shelley peered into the box. “But Millie, no one gets flowers from someone she doesn’t know, not flowers like that. They can’t be from a fan; they must have cost a fortune. Why, they’re the sort of thing a guy sends to a girl he—he adores, or something. I mean, they’re a love gift, you know? A—”

This time it was Shelley Winters who stopped talking suddenly.

Millie Perkins was crying.

Just for an instant. The next second she brushed the tear away angrily. She clutched the box to her, the flowers making wet marks on her blouse. And then she was running to her dressing room, the box in her arms.

For anyone who cared to listen, there was the sound of sobs coming from behind the door. But no one listened. The people left on the set were staring at each other in amazement.

They talked about nothing else for weeks.

But Millie Perkins, when she finally returned, dry-eyed, with her face set stiffly, never said a word.

Now it will be told

This then, will be for most of the people who stood bewildered on that set, the answer to the questions they asked so often—the eagerly awaited story never before told. The story of Millie Perkins, the little model making her movie debut in The Diary of Anne Frank. And most of all the story of the love she was forced to keep a secret.

It begins eleven years ago, when Millie was nine. It begins in a two-story brick house in Fair Lawn, New Jersey, on a Sunday afternoon. . . .

They had been up since 6:00 a.m., the whole family. At that ungodly hour they had been routed out of bed, blinking, sleepy, tousled—fourteen-year-old Janet, twelve-year-old Lulu, six-year-old Jimmy, baby Katherine, only three—and Millie, the in-betweener.

In the grey dawn Millie had pulled away from Janet’s hands shaking her awake. “Go ’way . . . too early. . . .”

“It’s six o’clock,” Janet hissed. “Come on, Millie, you’ve got to get up and get ready. . . .”

“Ready . . . fo’ . . . wha . . . ?”

“Why, you dope, don’t you remember? Daddy’s coming home today!”

Instantly Millie sat bolt upright in bed, her eyes wide open. “Oh! Of course! Oh, Jan—today!”

She threw back the covers. Janet was closing the window, turning on the radiator. “Listen, Mama’s washing Jimmy up. Hear him holler?”

They both listened for a minute. Then Millie, slipping into her robe and pattering barefoot into the hall, shook her head in wonder and disgust. “What a dope. Doesn’t he want to wash up for Daddy?”

But Jan was on her way back to her own room already, too busy to listen. There was so much to be done—so much. For Daddy was coming home—tall, blond, handsome Daddy who sailed the seas for the Merchant Marine and made it back to his family only once a month. And with him he brought into the house more than just himself, though that was enough. He brought excitement, romance, adventure. And he brought—authority.

For Daddy the house had to shine the way the glasses did on board his ship. For Daddy every dresser top, every table, must glow with polishing, every hairbrush must be lined up, neat, clean, orderly. The windows were washed, the house was swept, the bathroom and kitchen were scrubbed within an inch of destruction before Daddy came home. And that was not all.

On Daddy’s children, not a hair must be out of place, not a button undone, not a lace untied. For Daddy clothes had to be brushed, shoes shined, faces scrubbed. So that wonderful, long-gone Daddy, would smile approval and love upon his adoring clan.

Of them all, Millie was the one who worked hardest to please. Maybe because she was the middle one—neither the oldest, who got the most privileges nor the youngest who got the babying, nor the boy who could grow up to be a sailor, too. She was only Millie, who got her fair share of love, to be sure, but was still to herself, just the middle child, the quiet one.

The great moment came at last. For an hour the children had been lining themselves up behind the door with its brightly polished knocker. And then suddenly, just as they were dying with impatience, certain it would never happen—the key turned in the lock. The next instant their mother was clasped in Daddy’s arms and they were clutching him from all sides, laughing, half-crying, pulling at him, crowding closer to be kissed and hugged and smothered in his embrace.

“Now,” said her father, freeing himself from them all, “let me look at you, all of you. Not bad. No, not bad. But if you really want your shoes to shine, you’ve got to do better than that. Here children, take them off. I’ll show you how to polish shoes!”

And he did.

That was the homecoming. Today Millie laughs about it, reports cheerfully that they went through that sort of scene every month. But then—then it was just another case of being little Millie, who never quite managed to stand out from the crowd. In-between, nowhere-special Millie.

She might have felt that way forever if that particular miracle hadn’t happened.

When she was eleven she met The Boy, and he looked at her with special eyes.

If you’ve ever felt you were nobody and then suddenly you became somebody—then you know what Millie felt. You know a little something of the transformation that swept over her, of the joy that seemed about to lift her off her feet and carry her away, of the incredulous, shouting-out love that she could feel—even at eleven.

For this was not just any boy. This was a special, wonderful, brilliant, popular boy. This was the boy who led in everything—athletics and discussions, class plays and picnic plans.

It was magic. For she had been given by him the greatest gift of all, more precious than the envious eyes of the girls, the whistles the boys now bestowed upon her. She had been given herself!

And since that gift could never be revoked, that love could never die.

Busy improving

At home, she was still little Millie, still eager to please, quick to love. Her father liked to see the children busy with improving things, so whenever he was by, she would snatch up a book and pretend to be immersed in it. One day he walked past her chair and found her apparently intent upon a book on how-to-raise-chickens. This time she got the recognition she had longed for—her father was tremendously impressed with Millie’s practicality, her varied interests. A year earlier it might have cut her to the quick that when she finally got praise it was for a lie—but now she was not alone, now she could no longer believe that that was the only way she could be loved.

Didn’t the boy love her for herself? Didn’t he believe in her for what she really was?

When high school was over, the future seemed perilously near. Lots of the kids were getting married right after graduation, starting out in small jobs and smaller apartments.

“We could, too,” the boy said to Millie. “But we won’t.”

If she was disappointed, she said nothing, trusting him. “Tell me—”

“I’m going to college. Then to medical school. It takes a long time to be a doctor, eight or nine years. It wouldn’t be good for either of us to be trying to start out a marriage while I had to study and sweat over the books. We’ll wait.”

Panic hit her. “Where will you go?”

“Not far. You could go to college, too, you know. Your folks would send you.”

She shook her head dolefully. Much as she wanted to be with him, lost as she would be without him, she was no student by nature and she knew it. The thought of a college campus, filled with brilliant young people expounding difficult theories was too much. “No. . . .”

He nodded, understanding that his girl had come far, but would never be filled to bursting with self-confidence. “Very well, then. You come to New York and get a job. We could see each other every week end. You could live with your sister.”

“With Lulu? That would be great.”

Millie thought it over. Lulu had a darling apartment, was easy to get along with. “But what would I do? I haven’t got any training for anything.”

The boy took her hands and looked into her eyes. He had an idea; he’d been saving it for the right moment. Now this was it.

“Honey, you could be a model!”

Millie’s eyes positively bulged. For a moment she was utterly speechless.

“Me? A model? You’re crazy. I—I know you think I’m—pretty—but nobody else—I mean—”

The boy waited till she ran down. Then he led her, still holding her hands, to a mirror. “Look!” he commanded. “Look at your eyes, look at your mouth—Millie, I don’t know if you’re pretty, really. But I do know people look at you. I do know you take a great picture. And I know—I know you can do it!”

Slowly, Millie turned to face the mirror.

And a year later, she was one of the top models in New York City.

Life in the big city

All week, she carried her model’s hatbox, filled with make-up, clothing changes, skin lotions, from photographer to photographer, posing in glamorous clothes, collecting fabulous fees. Evenings she returned to Lulu’s pretty apartment to eat Lulu’s marvelous cooking along with Lulu’s fascinating guests. All sorts of interesting people came over—writers and musicians and artists—many of them eager to meet Lulu’s stunning little sister whose face peered so pertly from the pages of the fashion magazines. But to Millie they were a terrifying crew, full of confidence and grit and strong ideas. She admired them and envied them—but she was much too shy to talk to them. The life she herself was leading never struck her as really unusual and interesting.

As far as she was concerned, she lived for the week ends with her guy.

Life was good and easy and smooth. Until everything happened at once.

On the same day, she was asked to test for Anne Frank, and he received his draft notice.

All week end they argued it back and forth, over and over.

“But I can’t act. I’ve never acted.”

“If you can’t act, you won’t pass the test. Let them decide that! Millie, dear.”

“I’ll make a fool of myself.”

“Cary Grant flunked his first screen test. Clark Gable flunked his first screen test. Lana Turner—”

“She passed hers!”

“So will you!”

“That’ll be even worse! I don’t want to go so far away from you.”

“Honey, I’m going into the Army. They might send me to Japan—how do we know?”

“Oh, they couldn’t—”

“And just think—California’s a lot closer to Japan than New York is!”

As always, his confidence in her won the day. She took the test. But it was not his confidence that won the role—it was the serious dark eyes, the shy smile, the delicate face, the hidden talent that made her be the sensitive little Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis.

By the time the tests were analyzed, by the time the part was hers and she had gotten the—to her—unmitigated gall to sign a seven-year contract for doing something she’d never done before, her fellow was indeed in the Army. He hadn’t been sent to Japan but he had made sergeant and he was definitely—busy. So they were prepared, or almost prepared for separation.

When he put Millie on the plane for the coast, she was determinedly cheerful. “At least,” she said, “we’ll have plenty of money for your med school. We won’t have to wait any more to get married.”

The sergeant puts his foot down

Very seriously, he took her into his arms. “Millie, darling, maybe we won’t wait any longer once I get out. God knows I don’t want to. But we won’t use a penny of your money. Not a penny.”

Startled, she drew back. “But whatever is mine belongs to you. Just as yours does to me. It’s always been like that.”

“Not where it comes to that. I’ll save my Army pay, sweetheart. I’ll have a lot put away. I’m not going to live off you no matter how much you make. So buy yourself half a dozen assorted shades of mink, Millie. The money is all yours.”

In her first interview with the big brass of the studio, she heard the words: “and then your next picture. . . .”

She interrupted shyly. “Well, you’ll have to give me a little time off. For—for a honeymoon.”

The silence fell like a lump of lead. “You’re—engaged?”

She nodded. She always felt better when she could talk about her fellow. “Oh yes. Since high school. He’s in the Army, but when he gets out we’re getting married. Then he’s going to med school.”

She looked around the room, her eyes shining. But the men weren’t looking at her. They were shaking their heads.

“What’s the matter?”

“Look, Miss Perkins—Millie. This is hard to explain. But you’re a newcomer, right? And actually, this picture rides on your shoulders. You’ll make it or break it. So—we have to sell you to the public. Get them to know your name, wonder about you, want to see you. See?”

“Yes—”

“Well, the best way to do that is—well, for them to see your name in the papers. In the gossip columns. Millie Perkins seen at the Mocambo with So-and-So. Millie Perkins, out dancing with Joe Doaks, says her favorite joke is. . . . You know.”

Millie’s face was white. “But I can’t. I can’t go dancing with anyone at all. I’m engaged. And I don’t want to. I haven’t gone out with another boy for—”

They nodded, soothingly. “But he would understand, wouldn’t he? That it was really just for business? Then after the picture Is over, you could announce your engagement. He’d understand, you know.”

“Maybe he would,” Millie cried out. “But I wouldn’t. I’m sorry. I can’t do it. Not for anyone. I’ll go home tomorrow, today. But I—”

They all talked at once then. In the end, they talked her down. Not on dating. She could no more do that than cut off her arm. But they persuaded her to let them pretend even if she wouldn’t.

“Yes,” poor Millie said miserably. “I guess. I mean—well—”

But she couldn’t hold out against them. For the first time since she was eleven, she was alone again—and she please them, had to have their approval, their praise. Alone, she just wasn’t strong enough to defend herself.

And so she set out to live a lie. Millie Perkins, whose face turned red at so much as an evasion, faced interviewers by the score with her lie in her mouth, burning with shame. Reporters found her shy, diffident, noted that as soon as they got onto personal topics, her voice seemed to fade away. If they pushed it further, she might stop talking altogether. Or, sometimes, an angry spark might finally flare in her cheeks and then they would go away wondering what Millie Perkins had to be so snooty about. The stories that went out to the papers contradicted each other over and over again.

Millie Perkins at the Mocambo with George Stevens, Jr., son of the director of The Diary Of Anne Frank.

Millie Perkins’ favorite Hollywood dates are Nick Adams, Barry Coe, Tommy Sands, Gary Crosby, Dick Sargent.

Millie Perkins, new find, never dates; she’s too busy studying her Anne Frank script.

Millie Perkins has never had a crush on a boy since a six-year-old intrigued her in grammar school. When that died out, she never found another.

Millie Perkins went steady with three boys at once in high school. . . .

And so on. Once and only once the reports were true: Dick Beymer, who plays opposite her, took her to a ballet.

“But that wasn’t a date,” violently to a reporter.

“Why not?”

“Because he didn’t ask me. I asked him. I wanted to go and so—”

Joseph Schildkraut, who plays her father, saw her tremendous embarrassment, came to her rescue. boomed to the reporter. “I love her!”

The reporter went away confused, but satisfied.

After that, because he played her father and because he was kind and she was too lonely to bear it, she told Schildkraut the truth. Later, as she grew closer to Shelley Winters and Nina Foch, losing her awe of them in the warmth of their kindness and affection, After that, things were a little better.

But not better enough. At night, after she has cooked, burnt, and eaten her dinner alone, after she has studied her lines and written her long, nightly letter to the Sergeant—after that, the tears still come. And because she is too bound by her love to date, too tied by her lie to seek friends, she remains alone and desolate.

Perhaps by telling this story for all the world to see, we have brought an end to loneliness for Millie Perkins. Perhaps it may even be seen that a love story is not duller than gossip, that truth is something more precious than a useful lie.

We hope so. We would like to see an end to the lie, an end to the loneliness. We would like to know more about Millie’s guy, their plans, their future.

We would like to share their love.

THE END

Millie will soon be seen in THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK for 20th-Fox.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958