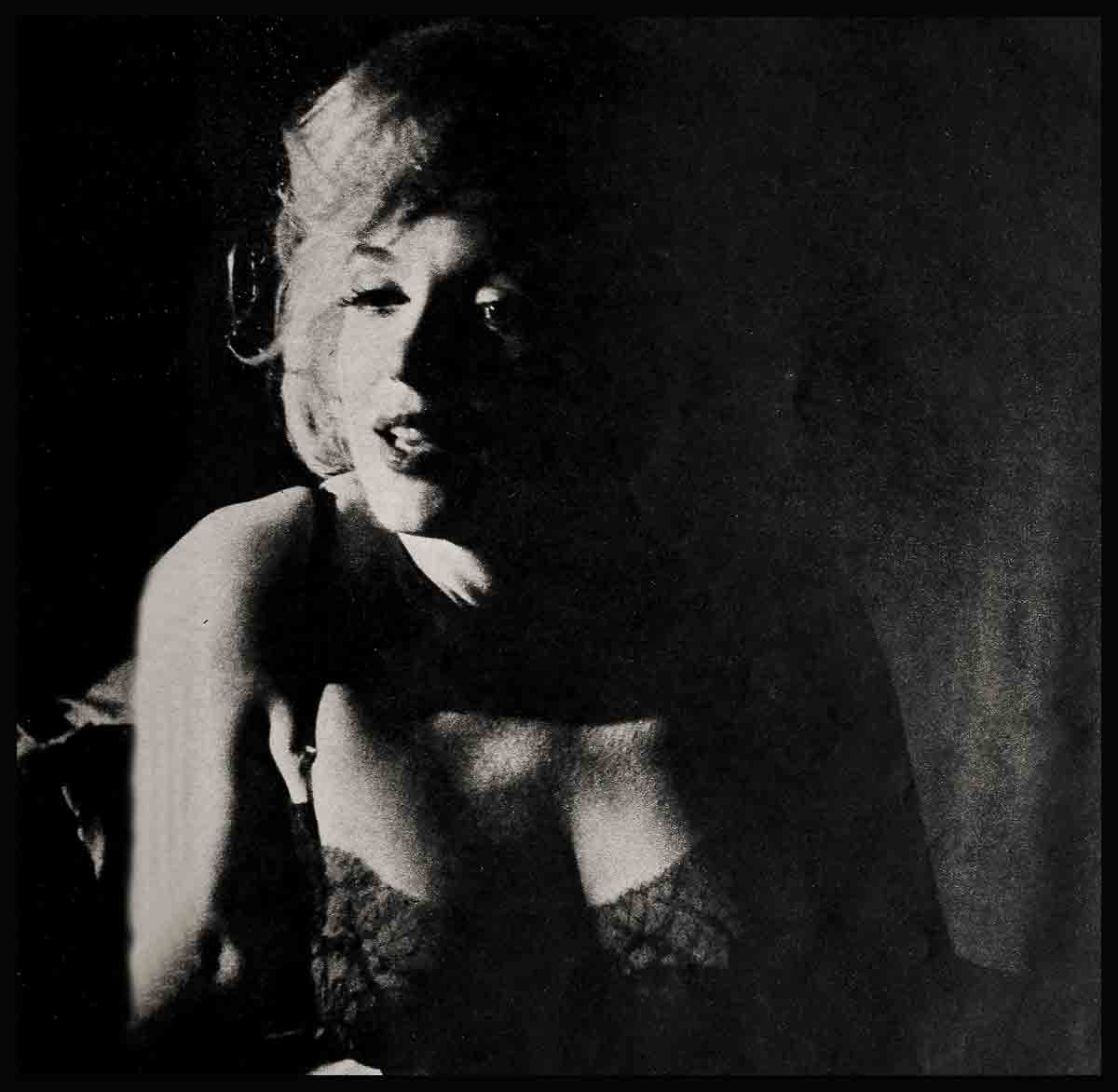

Marilyn Monroe: “. . . Don’t Worry About Me . . . Please Don’t Worry . . .”

“Please,” Marilyn Monroe said to the doctor, “would you say that once more, what you said about the tests?”

The doctor smiled.

His patient looked so eager, so hopeful.

“They show that you’re going to have a baby,” he told her again, gently.

Marilyn’s face flushed. She had come into the office a few minutes earlier, tired-looking, very tired. But now she was suddenly radiant. And nearly speechless.

“A baby?” she asked.

“Oh,” she whispered then, still not quite believing it. But when, a moment later, the simple, beautiful message had sunk in, she rose from her chair. And this time she cried it out:

“Oh . . . Oh, thank God. And thank you, Doctor . . . I’ve got o get back to the hotel, right away, Doctor and phone Arthur and tell him the good news!”

The doctor rose now, too.

“Your husband went back to New York?” he asked, as he walked toward her.

“He left last night, for some business conferences,” Marilyn said. “Just last night . . .”

“I see,” the doctor said. Then he took her arm and led her back to her chair. “Well, there’s no reason you can’t call him from here—in just a few minutes But,” he went on, satisfied that she was seated again, “there’s a little matter I’d like to discuss with you first. The matter of taking care of yourself.”

“Of course,” Marilyn said, nodding.

“In order,” the doctor continued, “to avoid a repetition of what happened last time.”

He minced no words.

“A miscarriage is an awful thing, as you well know,” he said. “It can be caused by a number of things. That too, you know. In your case the cause seems to be a hormone deficiency. Now, that we can help along. But where you must help yourself is in the very simple area of taking-it-easy. Especially for the first three months.”

Again, Marilyn nodded.

“Arthur and I live very quietly—” she started to say.

“A good start,” the doctor said, interrupting her. “But how about your work? You’re busy on a picture right now, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” Marilyn said.

“Can you get out of it?” the doctor asked.

“Not at this stage,” Marilyn told him. Smilingly, she added, “The picture’s two-thirds finished, though—only another month to go. And all the hard work, the strenuous work—I’ve already finished with that.”

The doctor stared at her for a moment.

“How,” he asked, slowly, “would you define strenuous work?”

‘Well yesterday, for instance,” Marilyn said, describing the scene, quickly, gayly, energetically, “I had to run up stairs. The picture’s called Some Like It Hot and I play a flapper back in the Twenties who leads an all-girl band. And so there I am, in this one part, wearing this tight-tight dress, running away from somebody—running up these stairs. And yesterday—oh, I’ll never forget it—yesterday was the day the scene had to be shot. And what should have been very simple to do became very hard, for some reason—this funny feeling in my stomach, I guess, that kind of held me back. And so I did it once, and I did it again and before I was through I’d done it fourteen, fourteen times.”

The joke wasn’t funny . . .

She laughed when she was finished.

But the doctor didn’t.

“A funny feeling in your stomach, you say?” he asked.

Marilyn nodded.

“Fourteen times up those stairs?” the doctor asked.

Marilyn nodded.

And then, suddenly, she saw the worried look on his face.

And her own voice became worried.

“You’re thinking,” she said, “that I was as pregnant yesterday as I am today—isn’t that right, Doctor?”

She watched him as he closed his eyes for a moment and thought.

“Isn’t that right, Doctor?” she asked.

“Mrs. Miller,” the doctor said. “What’s done is done. What you know today you didn’t know yesterday. Now only tomorrow is important. And from tomorrow right up until next June you must take it easy, easy, very easy.”

“Yes.” Marilyn said, studying the look on his face, watching it as it turned from deep-seated worry into what appeared to be a very uncomfortably forced smile.

“So,” the doctor said, tossing up his hands, “I’d say that’s it for this meeting. And now, if you’d like, I’ll step out so you can phone your husband and tell him the good news, All right?”

“Yes,” Marilyn said, still studying his look as he walked across the office, toward the door.

When he was gone Marilyn sat alone now and she thought, and the doctor’s words of a few minutes earlier came back to her mind.

A miscarriage is an awful thing, as you well know. . . .

“I know,” she found herself saying, aloud.

“I know.”

She remembered the day—nearly fifteen months ago—when she had first known.

It was a Thursday, in August, in the little house on Long Island she and Arthur had rented for the summer. It was a day of pain, intense, unbearable, a day that began with a child inside her and that ended with the child suddenly gone.

And then, she remembered, it was night, in the big white quiet hospital room in nearby New York, with her husband standing by her bed, watching her come slowly out of her shock, listening to her as she wept about what might have been, as she moaned, “I’ve failed you, Arthur, I’ve failed you, Arthur, I’m only half a woman . . . because I’ve failed you and I’ve failed our baby.”

She brought her hand up to her forehead now.

It was hot, and covered with perspiration.

She rose from her chair and walked over to the doctor’s desk and picked up his phone.

“I’d like to place a call to New York,” she said, her voice uneven, breaking as she spoke.

She gave the operator the rest of the information and then she waited.

The day before

Once more, Marilyn, she heard the voice cry out suddenly.

She remembered yesterday, on the set, the whole crew standing around laughing along with her as she did the scene.

“Up those stairs, again?” she remembered herself asking the director.

Once more, Marilyn, she remembered the voice cry out.

And then again:

Once more, Marilyn!

And then again:

Once more, Marilyn!

But now, suddenly, thankfully, another voice cut in, this one coming from the phone receiver she gripped.

“Marilyn?” it asked. “Is that you, darling?”

“Arthur?” Marilyn asked back.

“Yes,” she heard him say. “Is everything all right?”

Marilyn was sobbing this time and the words came hard.

“Arthur,” she said, “can you come out here, right away? . . . I need you, Arthur . . . I need you so much.”

She listened as he asked her where she was calling from, what the matter was.

“It’s our baby, Arthur,” Marilyn told him. “We’re going to have a baby . . . and I don’t want it to be like last time. Oh God, I want it to be born alive and healthy and I don’t want it to be like last time. . . .”

The next four weeks were strange and troubled.

Arthur had flown to Hollywood immediately after hearing from Marilyn and his presence helped make up for almost everything else that was going to happen.

For what would happen during those thirty-odd remaining days was not to be good.

Marilyn began to feel sick soon after her visit with the doctor. Mornings, especially, she would wake up with the alarm at 5:30 and a few minutes later, invariably, the nausea would fall heavily on her.

“Please, just today, stay in bed and forget the picture,” Arthur would say.

“How can I?” Marilyn would ask. “If I don’t go—all that money they’re spending—all those people who don’t work—”

“But you, Marilyn,” Arthur would say. “How about you and the way you feel?”

Most mornings, Marilyn would try to fight off her sickness, go to the studio and put in a nine and sometimes ten-hour day.

But, finally, it became too much for her. And, finally, the morning came when she could not move from her bed.

The secret they shared

Arthur phoned the studio. He said that he was sorry, but that his wife would have to be excused from work that day.

“Why?” he was asked.

Arthur wanted to tell them. “She’s pregnant,” he wanted to say, proudly and angrily, at the same time, “is that a good enough reason for you?”

But Marilyn had made him promise that he would tell no one, not yet.

“It was an important thing with her at the beginning,” someone close to the Millers has since said, “that word about the baby should be kept from everyone for as long as possible. I think what caused it was the fear in Marilyn’s mind that to spread the good news might somehow spoil things, and her mind went back to the endless commotion that had been made over her first pregnancy and she felt that this time no one should know—at least, not until the first big danger period was over.”

And so Arthur, now, keeping his promise, phoned the studio and said simply that his wife needed the day off.

“But why?” he was asked, again and again, frantically.

“She’s not too well,” he said, minimizing the matter as best he could. Then, looking over at the bed for a moment, seeing Marilyn lie there—moaning, her hands pressed hard to her head—he said, “I think a day in bed would do her good.”

And with that, he hung up.

And the reverberations to that clink of receiver to hook were tremendous.

Within hours, the word had through Hollywood.

A few people guessed at what might be wrong.

But quite a few other stopped only long enough to make jokes and snide asides.

“The queen is weary,” they said.

“Poor Marilyn—after three years of resting in New York she comes back to work and then she decides she needs a little more rest,” they said.

“La Monroe,” they said, trying to pull a Garbo. But lest she forget, Garbo disappeared only after her pictures were finished.”

In time, the remarks—these and more, many more—reached Marilyn.

At first, she laughed.

“Gee,” she said, amused, the way you would be if suddenly your next-door neighbor passed the word that you were going around telling people you were a close relative of the Queen of England.

But, after a while, Marilyn found she couldn’t laugh anymore.

The stories, the remarks, the cold looks she received on the set when she was finally able to return to it—all of this combined to build a terrific pressure within her.

And, though she took it quietly, bravely, smiling back at those who laughed at her, she realized she couldn’t keep taking it forever.

The camouflage

And on the mid-November afternoon the last scene of the picture had been shot, she got into her car and raced to her husband and she begged him to take her away, back to New York, as quickly as possible.

She lay on the bed and wondered if it would be all right to get up for just a little while and go out and take a walk. She’d been in bed these past few days—almost a week now; ever since she and Arthur had come back to New York from Hollywood. And because she knew how important it was to rest now, she’d lain in bed this past week, obediently, happily, never once complaining.

And yet on this day, at this moment, she felt strangely different.

She wanted to get up.

She wanted to go out.

She wanted, more than anything, to take a little walk around the block and—for just a few minutes—to breathe in, luxuriously, freely, the crisp, cold Eastern air she liked so much.

She turned in her bed.

“Should I?” she asked herself.

And then, slowly, realizing that her doctor hadn’t said anything about staying in bed every minute of every day, feeling the age-old privilege of pregnant women to indulge in their cravings—whether for fancy foods or for a simple walk—she got out of the bed, dressed in what she and Arthur always jokingly refer to as The Camouflage—a dark outfit, successfully designed to make Marilyn as inconspicuous as possible—and, stopping only long enough to tell a cleaning woman who was working in one of the other rooms that she would be out for a little while, she left the apartment. . . .

The toy store she came to while on her walk was neither big nor fancy.

But toy stores had always fascinated Marilyn, ever since those days of her childhood, when she was a little tawny-haired thing with no toys of her own—ever since the early days when the closest she came to being withdolls and games and little tin tea sets meant leaving whatever house she was living in for the time being and walking secretly to the local toy store and standing outside, her face pressed against the window, looking in.

As she had stopped to look now, years later, for just a moment or two.

And it was just before she was about to continue her walk when she saw it, the little stuffed kitten, sitting in a corner of the window.

A tiny gift

It was a strange little kitten, brown, fluffy, warm-looking—but with the largest and saddest eyes.

“Poor little thing,” Marilyn found herself thinking, as she stared at it, “I bet you’re so sad because nobody wants you. And I bet nobody wants you because you’re so sad.” She laughed to herself.

She shook her head.

“I bet, though, that there’s a baby somewhere who would love you, who—”

And then she stopped.

And she thought of a baby—not of the one she knew best, the one who though not yet born was already beautiful in her mind, the one who would be hers one day this summer, hers and Arthur’s, but, for now, of the tiny baby—a little boy—of a friend, whom she had seen once since his birth, whom she loved from that first moment and whom she could picture now lying in his crib and lifting his small chubby hand and hugging it against the side of this sad kitten’s face.

She hadn’t yet bought a gift for this baby, she thought to herself.

She’d planned, in the back of her mind, to go to one of the plush stores over on Fifth Avenue when she was feeling better and buy him something big and expensive, something to fit in with his beautiful nursery décor and with everybody else’s oohs-and-abhs.

But now, as Marilyn stood there, looking in the store window, at the sad-eyed little kitten, she thought to herself that this, this was the perfect gift for that baby.

So she walked inside the store and bought it.

And it was while she was on her way back to the apartment, carrying her package snug under her arm, that the tragedy began.

It began with a sharp, momentary pain in her stomach.

She stopped.

She waited.

“No,” she whispered to herself, remembering the feeling from another time, that other time. “No . . . Don’t come back again. Please don’t come back again.”

But, a second later, it did come again, sharper this time, longer.

Marilyn’s face began to pale.

“No more,” she begged, inwardly. “No more.”

But again her plea was in vain.

Because again the pain returned.

Marilyn clenched her teeth.

She took a few steps forward, down the street.

Somehow she managed a few more steps, and then a few more, and then a few more.

And, finally, she was back at the apartment.

“Arthur,” she called as she walked through the door.

She knew he was not home, but still—sensing what was beginning to happen—she wanted him now and she continued calling desperately for him. “Arthur!!!!”

She was sobbing and leaning against the wall, her blonde hair brushing wildly against a small gay delicately-lined painting, when the cleaning woman rushed in from the next room.

“What’s wrong, Mrs. Miller—”

But then, seeing that something was very wrong, she put her arm around Marilyn’s waist and very gently led her into the bedroom.

And then she rushed for the phone. . . .

The sad-eyed kitten

“Arthur?” Marilyn asked, looking up from the bed, at her husband.

It was nearly two hours later now and Marilyn had just opened her eyes. The doctor was standing on the other side of the bed, but she did not see him. He had administered drugs to her earlier, drugs which had at first sent her off to sleep and which now left her only groggy but, temporarily, without any pain.

“Arthur?” she asked again, her voice floating through the air like a lonely cloud, lightly, almost as if without direction.

Yes,” her husband whispered, nodding putting his hand into hers.

“I’m glad you’re here,” Marilyn said. “I knew you’d be here.”

She smiled at him and he smiled back.

And for the next few moments they looked into each other’s eyes, the man giving courage to his wife, the wife accepting that courage, though not alert nor awake enough at this point to know why.

“Arthur,” Marilyn said then, after a while, her eyes shifting from Arthur’s face to the bureau behind him, “—would you open my package . . . over there?”

Her husband turned and saw the package and, slowly, he opened it.

“Oh yes,” Marilyn said, remembering, when he’d completed the job, “it’s the kitten, the little stuffed kitten.”

Her husband held it up, so she could see it better. He did not ask where she had gotten it, nor why. But he could see at this moment that it was very important to her. And so he held it up, and he watched her now as, almost happily—it seemed, she began to talk to it.

“Don’t worry, don’t worry,” she said. “I’m not feeling too well now. But I’ll be fine tomorrow. And then I’ll take you to the boy I said would be your friend. Yes, tomorrow. . . .

“And then, then, someday there will be someone else you will play with—another little baby who will come to visit you and your friend and who will want to play with you, too. Then the three of you will play together . . . But, for now, you mustn’t worry about me. You mustn’t worry. . . .”

And thus did Marilyn, in her desperate grogginess, believe that everything was going to be all right.

For she had no way of knowing now, in her state, that in just a little while the drugs would wear off and the terrible pain would come back to her stomach, that the doctor standing on the other side of the bed would look over at her husband and shake his head, that the little sad-eyed kitten she spoke to now would never know the precious little baby, soon to die, inside her. . . .

THE END

Look for Marilyn in SOME LIKE IT HOT for United Artists.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1959