North To ’Frisco—Gregory Peck

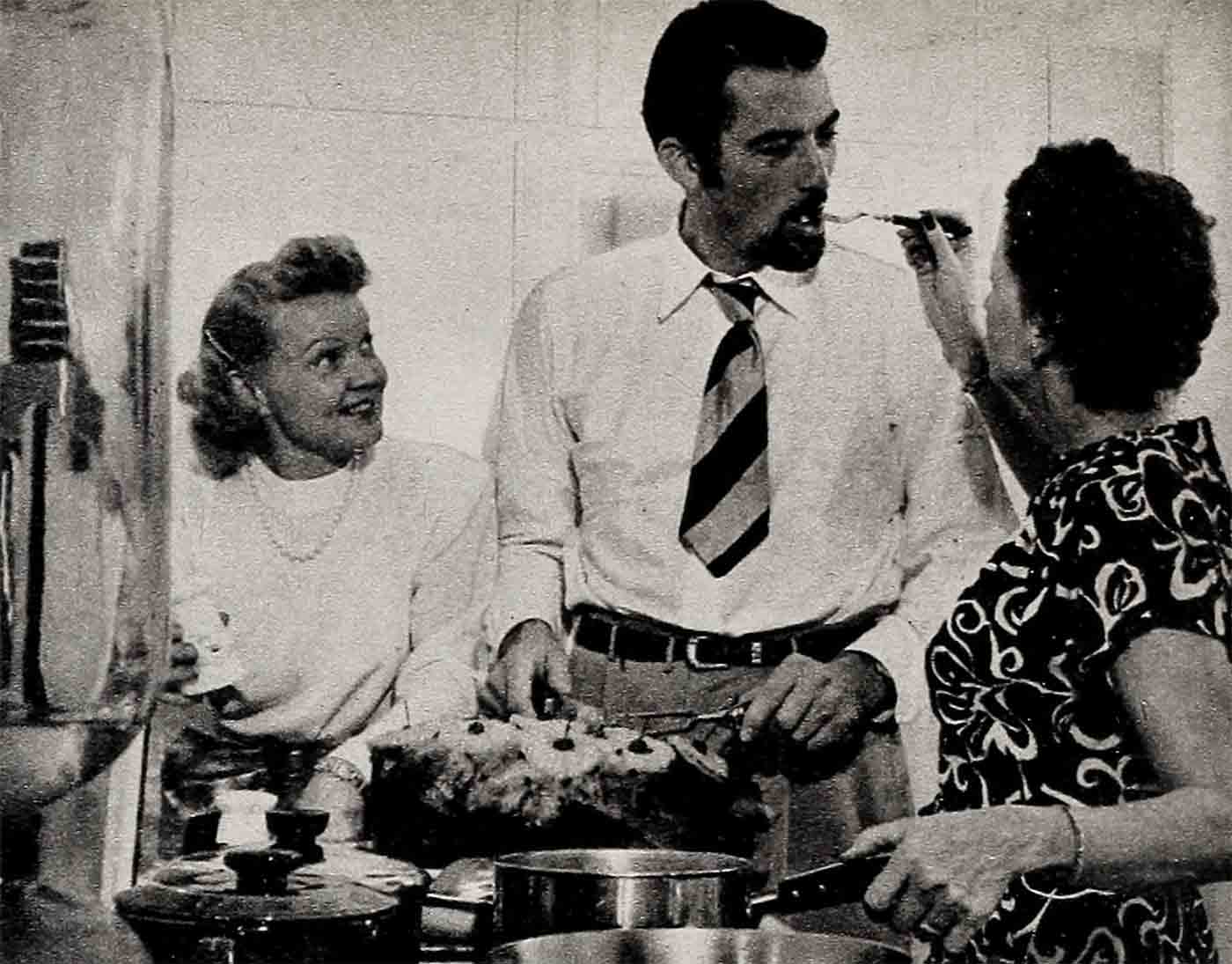

As 1947 drew to a close, Gregory Peck grew a black beard, donned the frock coat Clark Gable wore in Gone With The Wind, and set about driving Laraine Day crazy in San Francisco, Oakland, Sacramento, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

Greg was good at it, and Laraine went out of her mind prettily, to the applause of packed houses.

“Got to keep acting. Got to learn my business,” said Peck, who had just completed a spate of handsome pictures in Hollywood including Gentleman’s Agreement. “This is the kind of chance a motion picture actor doesn’t get often enough.”

The play was Angel Street, as you suspected. The same that Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman did on the screen under the name of Gaslight.

Western audiences were somewhat startled to see Gregory Peck playing a middle-aged villain on the stage, but they liked it, and Peck was getting precisely what he wanted—experience in a different, difficult kind of part. He took it so seriously he grew his own beard.

“Sheer laziness,” he explained. “Saves an hour or so a day makeup time.” It was a small beard, a Van Dyke, but few persons accepted it as real. They tugged at it. Greg Peck is probably by now the possessor of one of the most thoroughly inspected beards since the Smith Brothers. “I was considering having a sign made which would say, It’s real, but it’s all right. If people want to pull my beard, why let ’em.”

The stock company in which Laraine and Greg went on tour was. headed by Sheppard Traube, who directed the original Angel Street, on Broadway, and was inspired by Greg’s consuming passion to get on a stage and act. Had to get on a stage.

Weekends, Greg flew home to see Greta and the boys, and to supervise construction of a barn on his new estate. Late evenings and non-matinee days found him at Fisherman’s Wharf consuming shrimp, or looking up Chinese friends. Greg admires Chinese, holds that they are probably the most ethical and the most honest people in the world. In San Francisco, he ate late snacks sr prepared by his mother, who lives there, and raided her icebox. When Greta came up for visits, he introduced her to fans as Sonja Henie, which embarrassed her. All told, he had a pretty wonderful time acting on the stage. But the beginning wasn’t as easy as all that.

The beginning was rough. He (Greg) started his idea for a super stock company many months before, in Hollywood, by paying a visit to his business manager, the astute Roland Mader, who heard him through patiently. Mr. Mader admires Art, good acting, and youthful enthusiasm. But Mr. Mader is convinced that the best way to succeed in life is to see that your check stubs balance with your bank account.

He regarded Peck solemnly.

“My good man,” he said, “you are nuts.” Consider a plumber. A plumber positively never plumbs anything just for the hell of it. And a writer will cheerfully let his children grovel in the neighbor’s turnip patch, starving to death, rather than get at his writing.

But actors—Mr. Mader sighed. Actors insist upon acting. Even when they have more picture commitments than a Brownie No. 2 at a family reunion, they will insist on running off somewhere to act in a barn. Mr. Mader now regarded Gregory Peck with disappointment.

Greg left his business manager’s office and put in a telephone call to Dorothy McGuire in New York. He talked rapidly for one minute.

“Yeah man,” said Miss McGuire.

Greg then got Jennifer Jones, also in New York, on the telephone.

“Why, shore,” said Miss Jones.

The next New York call was to Joseph Cotten. Greg talked for a minute. Joe talked for three.

After that, Greg took a plane to New York and gathered the clan in a hotel bedroom. Mel Ferrer, who directed Jose Ferrer in Cyrano de Bergerac, joined them. They dedicated summer stock to the gods, cast their proposed plays with glittering names, and never once bothered their heads about money.

Joe Cotten composed an elegant telegram to Miss Ethel Barrymore.

miss barrymore declines . . .

“Organizing most distinguished summer stock company in history of American theater. Deeply honored if you would consent to appear.”

In Hollywood, Miss Barrymore barely dropped two and purled one before she sent a singing reply:

“Thank you very much, my dear children, but I would rather die.”

It takes considerably more than a brushoff from a Barrymore to discourage young actors and actresses who are determined to act on the stage. There was a slight pause for studio identification while Greg finished The Paradine Case for Selznick and Gentleman’s Agreement for Twentieth, and while Joe and Jennifer completedPortrait of Jenny, but theatrical conversation was brisker than ever when they all met again in Hollywood.

What they wanted, they decided, was no ordinary summer stock company, but a thorough-going professional troupe, putting on plays in California with the same care that plays are put on in New York.

The idea finally came up as something to talk about in the presence of David O. Selznick. Mr. Selznick asked a couple of quick questions and said, “What are you waiting for? I’ll put up the money.”

Mr. Peck, Mr. Cotten, Miss McGuire, Miss Jones and Mr. Ferrer registered identical expressions—bug-eyed. And then grinned broadly and happily. Ought to have known all the time that Papa would come through. Several years ago, Papa had dropped $33,000 on three plays at Laguna, without batting more than one eye.

“David is a dead game sport,” said Joe Cotten later. “He also knows which side his income tax deductions are buttered on.”

“Go ahead, put on six plays,” said David O. “Be good for you.”

The result of this promise was a telephone call by Greg to prominent California Kiwanian, Frank Tarmon, Buick agent at La Jolla, California. La Jolla is Greg Peck’s home town, where his uncle, a redoubtable Democrat named Rannells, has been postmaster for thirty years with the exception of an unfortunate lay-off during the Hoover Administration.

La Jolla is where Greg learned to swim. You learn to swim instantly when older boys toss you off Alligator Point into water 25 feet deep. La Jolla is where Peck can walk all over town, greeting cousins.

“Act in a quonset hut?” said Mr. Harmon. “Naw. In the high school. The Kiwanians will sponsor you.”

So last summer the actors took over the high school, turned school rooms into dressing rooms, and laboratories into prop shops.

Planeloads of Hollywood celebrities peeled down from the clouds nightly to see Dorothy, Joe, Laraine Day, Dame Mae Whitty, Robert Walker, Ruth Hussey, Guy Madison, Eve Arden, Diana Lynn and Richard Basehart acting on the stage. The La Jolla season closed with Peck and Laraine in Angel Street.

Then it was David O. Selznick’s eyes that bugged. The figures were: income, $70,000; outgo, $75,000.

“Lost only $5,000!” Mr. Selznick muttered. “Why, this theatrical venture is practically a gold mine!”

Peck lost $2,000. He spent that much on telephone calls, travel, and room and board.

It sums him up. He says: “I’m not one of those personality boys so handsome all I have to do is appear in a picture.

“I have to keep learning. I have to keep looking for parts that make you stretch.”

It was after La Jolla was finished and done that Greg and Laraine went on tour with Angel Street, and ended up in San Francisco.

But first, Greg lounged for a while and counted his blessings. He’s come a long way. He thought of 1939, the year he got the job as a sideshow barker at the World’s Fair. Then there were the years of batting around Broadway, winning theatrical scholarships, getting parts, acting them well, but never managing to be in a play that was itself a hit play.

Then Hollywood, and nine starring pictures in four years.

“A good life,” murmured Peck, who was loafing for the first time in twelve months.

Stephen, aged one, and some pumpkins were obviously the production events of the year. Two big pictures. The La Jolla playmaking. The San Francisco playmaking to come. And the new house—with a swimming pool.

Peck gazed lazily at his elder son, a dark-haired child named Jonathan, aged three.

Jonathan was padding about under a fig tree, stamping his feet carefully.

“What are you doing, my good man?” Greg inquired politely.

“Stepping on figs,” said Jonathan.

“Why are you stepping on figs?”

“I am stepping on figs so that flies and birds can eat them,” said Jonathan.

Greg thought that over.

“Fine,” he said. “I am glad to see you have a social conscience.”

After a week’s beach vacation with Greta, who is Mrs. Peck, and whose blonde Lead comes to the middle button of Mr. Peck’s vest, Gregory and family returned to their new house near Pacific Palisades.

The house sits on top of a small mountain and has four acres around it on which Greg is hopeful of seeing horses someday.

Greg speaks often and seriously these days about Gentleman’s Agreement. This film has been publicized as a love story. It is that. But readers of the novel will know that it is also a forthright attack on anti-Semitism. Greg plays the part of the reporter who pretends to be a Jew in order to write a magazine article on his findings. (Last month in M.S., producer Darryl F. Zanuck told why he felt no other actor could do justice to the role.)

they pulled no punches . . .

“We never pulled a punch on the set, no matter what kind of visitors we had,” Greg says. “There was a governor, once, from a state not noted for liberal feeling. He was shocked. We went right on.

“We learned this, among other things: it is hard to detect all prejudice. You think you haven’t got any. You suddenly discover that you have—and you want to do something about it. That picture taught us things while we made it. I hope it awakens people when they see it.”

During the making of this picture, Greg took his work so seriously he became absent-minded about everything else.

He misplaced his automobile several times and reported it stolen, to the chief of studio police. It was always exactly where he’d left it. He hasn’t yet managed to do anything about the seven thousand letters he received every week after the picture started—letters commending him for appearing in it.

Neither has he had time to consider the problem of two prize Hereford steers presented to him by admirers in Texas. The Herefords broke out of their pen and ate $500 worth of Greta’s fancy camellias.

He does find time to pay a great deal of attention to his sons. He not only plays with them at every free moment, but has worked out a unique way to build up a bank account for them: for every day he works in a picture, he deposits one dollar to each boy’s account. The kids made $720 on Gentleman’s Agreement.

He has found a way to keep in touch with his 23 relatives in Australia and with his wife’s 23 relatives in Finland. Once a week, Greg and Greta compose a general letter, reporting on this and that in the life of the Peck family, have it mimeographed, and send it around.

Greg was in the new house for two months, before he began to wonder seriously why nobody ever called him on the telephone. He expected no studio calls, since he worked every day, but why, he said to Greta, does nobody else ever call me up?

“Dear,” said Mrs. Peck patiently, “we haven’t got a telephone.”

It’s been a busy year all right.

THE END

—BY CAMERON SHIPP

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948