Edmund Purdom: From Pauper To Prince

Edmund Purdom is the man I was prepared to hate. When this English actor was given Mario Lanza’s part in The Student Prince and Mario’s God-given voice along with it, I rebelled. I had heard those Lanza recordings for the picture and thought they were the finest he’d ever done. To me it was unthinkable that Metro would hand the part over to an unknown Britisher. I said so in my column and, among other things, predicted the picture would be laughed off the screen.

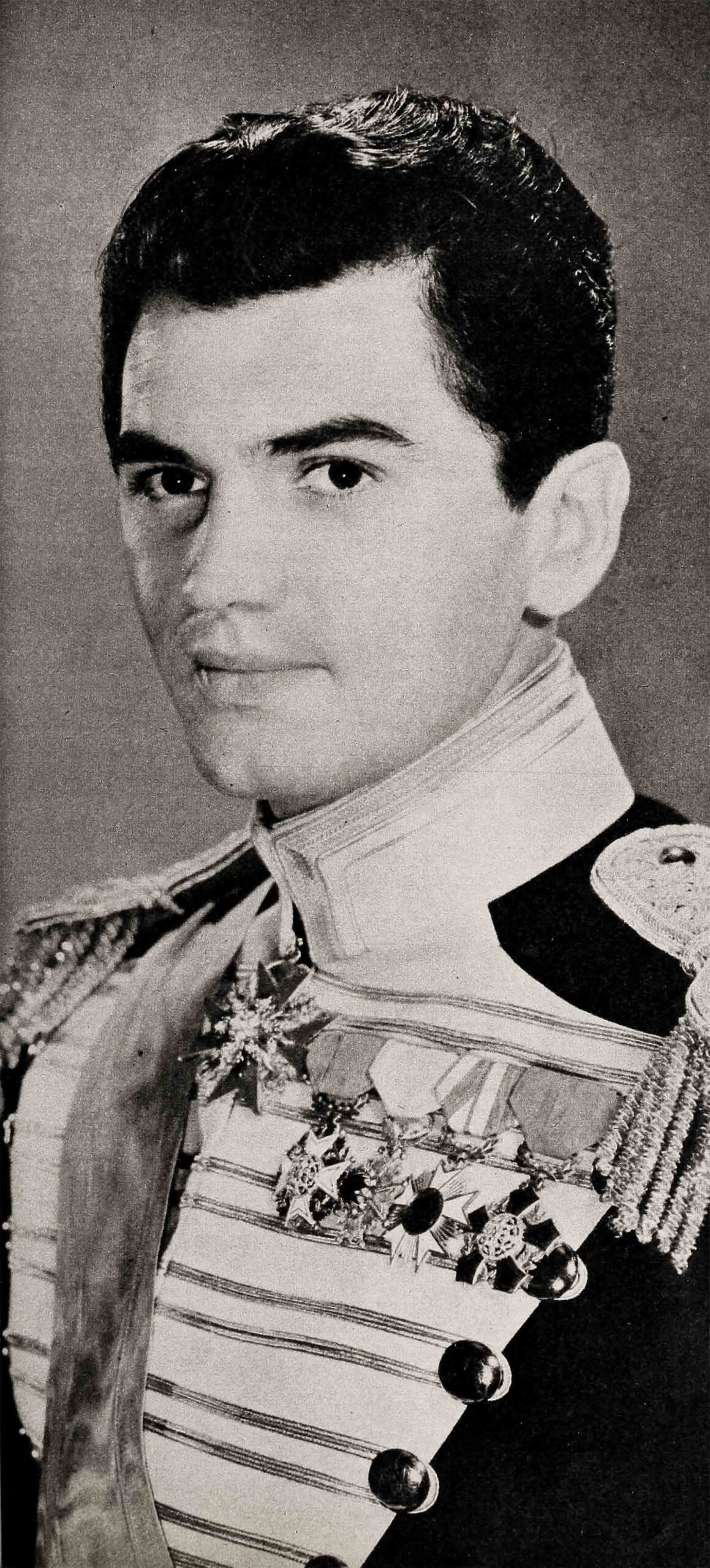

Words don’t taste bad. I know. I’ve just finished eating some of my own. I went to the preview of The Student Prince as a Lanza rooter—I still am. But when I left the theatre I was predicting that Edmund Purdom would be one of the biggest stars in Hollywood. He was terrific in the part—he really was a prince.

It’s an uncomfortable experience watching such a replacement as this, but I can’t blame MGM. They had lots of money tied up in the picture and when Lanza refused to work, they had to finish it somehow. The same thing happened after Marlon Brando walked out on The Egyptian. Purdom inherited that part also and after I watched him do some scenes on the set I came to the conclusion he was better in the part than Brando would have been.

Purdom didn’t want to meet me until I’d seen The Student Prince. He has a justifiable ego and he was angry at what I had written before seeing him on the screen. But my enthusiasm was so great when I did see him that the atmosphere was cleared, and we were buddies when he and his wife Tita sat down to tell me the story of their Hollywood struggles. I’m a sucker for a sob story.

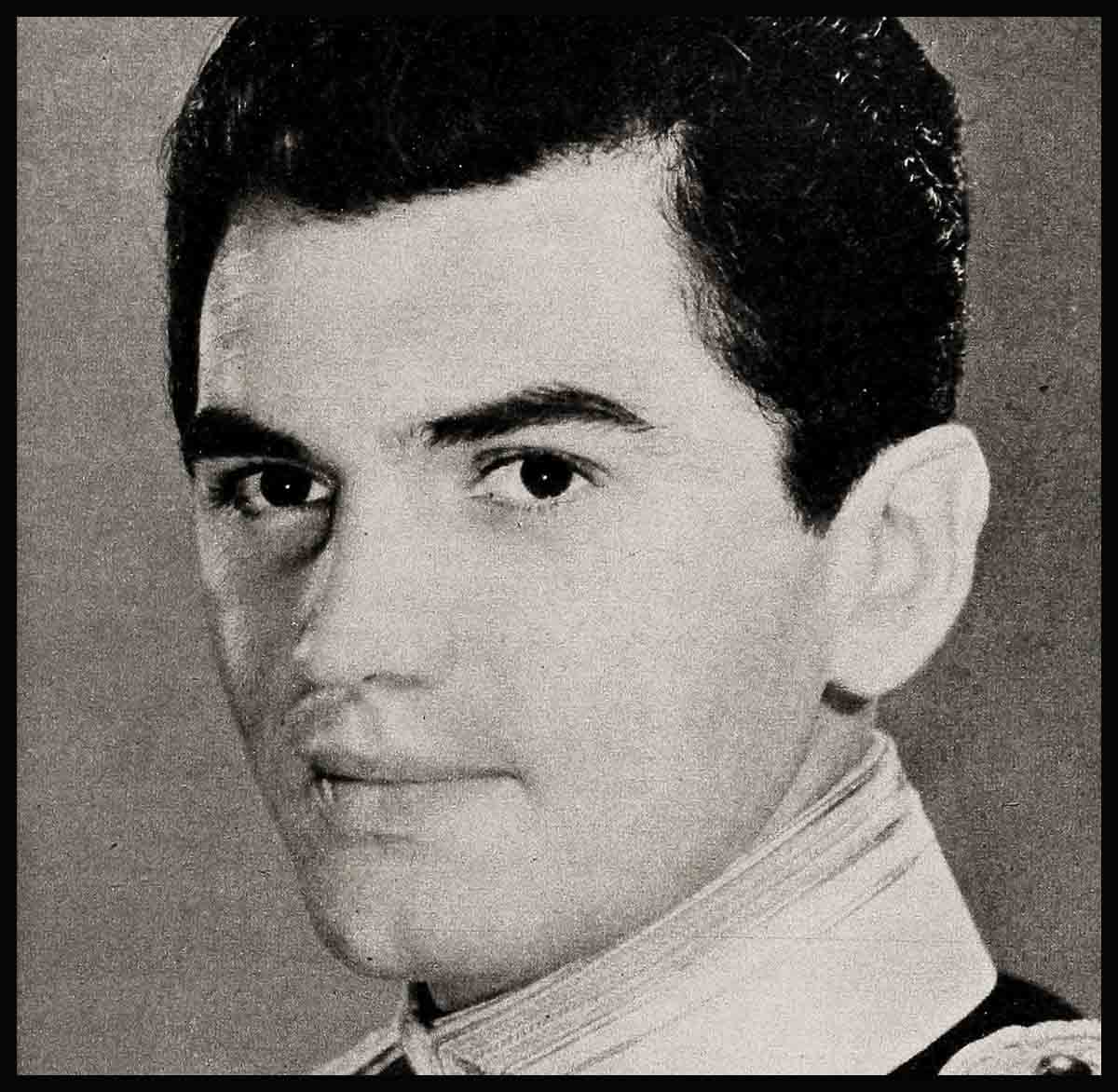

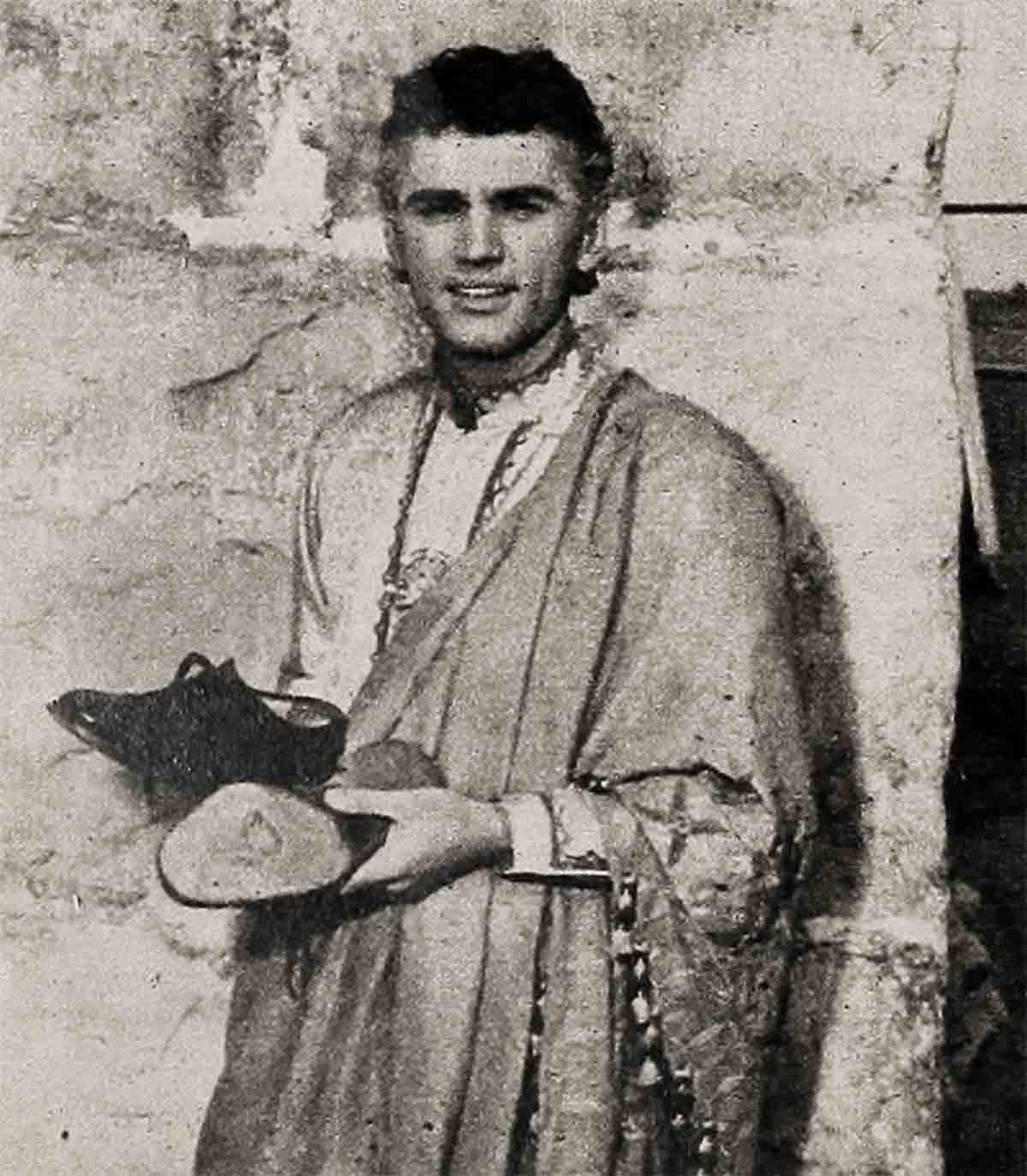

They’re a stunning couple. He has had $15,000,000 invested in him by two studios before the public has even had a chance to see him, Purdom is handsome in the romantic tradition—wavy black hair, dark eyes and classic features. Hollywood has tied the “glamour boy” tag on him but he’s a lot more than that. He has a fiery temperament, a cultural education, musical knowledge, talent and a world of charm. And his bubbling blonde wife Tita is as frank and communicative as a child; gay, pretty, talented (she’s a ballet dancer) with a rare zest for life.

When Purdom was thrown out of a Shakespearean acting bit at Stratford-on-Avon after what he describes as a “disagreement with the management,” famous director Tyrone Guthrie commented: “It won’t hurt him. He’ll either starve or be a star in five years.”

That was four years ago and both predictions were correct. It’s hard to think of these two as hungry, cold and so broke they didn’t even have bus fare. They were many times without a roof over their heads during a grisly year in which they fought for a foothold in movies. It’s harder to understand how some of their compatriots gave them nothing but such advice as: “Go home. There are too many Britishers here already.” Nor is it easy to conceive that agents told Edmund: “Your accent is hopeless. We can’t get parts for any more British actors.” But it’s heartwarming to learn that helping hands with folding money were held out by sympathetic strangers the Purdoms had met casually in their search for work—new friends who fed them.

Purdom’s salary jumped overnight from $350 a week to $2000 per. We met for dinner because he was working day and night and mealtime was his only chance to talk. The Purdoms arrived in a sleek Alvis.

“This is a celebration,” he told me. “We got our things out of hock this afternoon. Tita’s wedding and engagement rings and her father’s watch—they’ve been in and out of pawnshops a dozen times this past year. We paid interest so they wouldn’t be sold—two dollars a month—and sometimes we went without dinner to scrape the money together.”

“But how,” I asked, “did you ever get into such a jam?”

“I came here for a contract test at Warners,” Purdom said. “We had been in New York. I had a small part in Caesar And Cleopatra with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. The arrangements for the test had been made in London when a scout saw me there. At the close of the play Warners advanced me $600 and a ticket to Hollywood. By that time practically every studio here had offered me a test, but I was committed to Warners. I felt if that didn’t work out, I was pretty certain to land something else. Twentieth offered to test me for My Cousin Rachel, among other things. When I accepted the $600 advance I cut myself off from having my fare paid back to England by the Olivier company. So I made the Warners test with Mike Curtiz, but nothing came of it.

“It didn’t happen so quickly, however. There was a month of encouragements and delays before my option was dropped. Tita had joined me here. My chance at Rachel was gone as Richard Burton had been signed. Other things were cropping up and Mr. Curtiz advised me to stay on and Tita and I talked it over and agreed this was the time to gamble as both Universal-International and Twentieth were offering tests for a contract. I decided on Twentieth. The test was made by Sammy Fuller. It was a sort of a Scotland Yard thing, a fast-talking detective. It was without meaning and when studio heads saw it they lost interest. Then our finances were almost gone but I wasn’t afraid. I thought Id take a job at anything, any sort of work, to keep going. But when I tried to get work at a market I learned that my visitor’s permit allowed me to work in America only in a picture studio.”

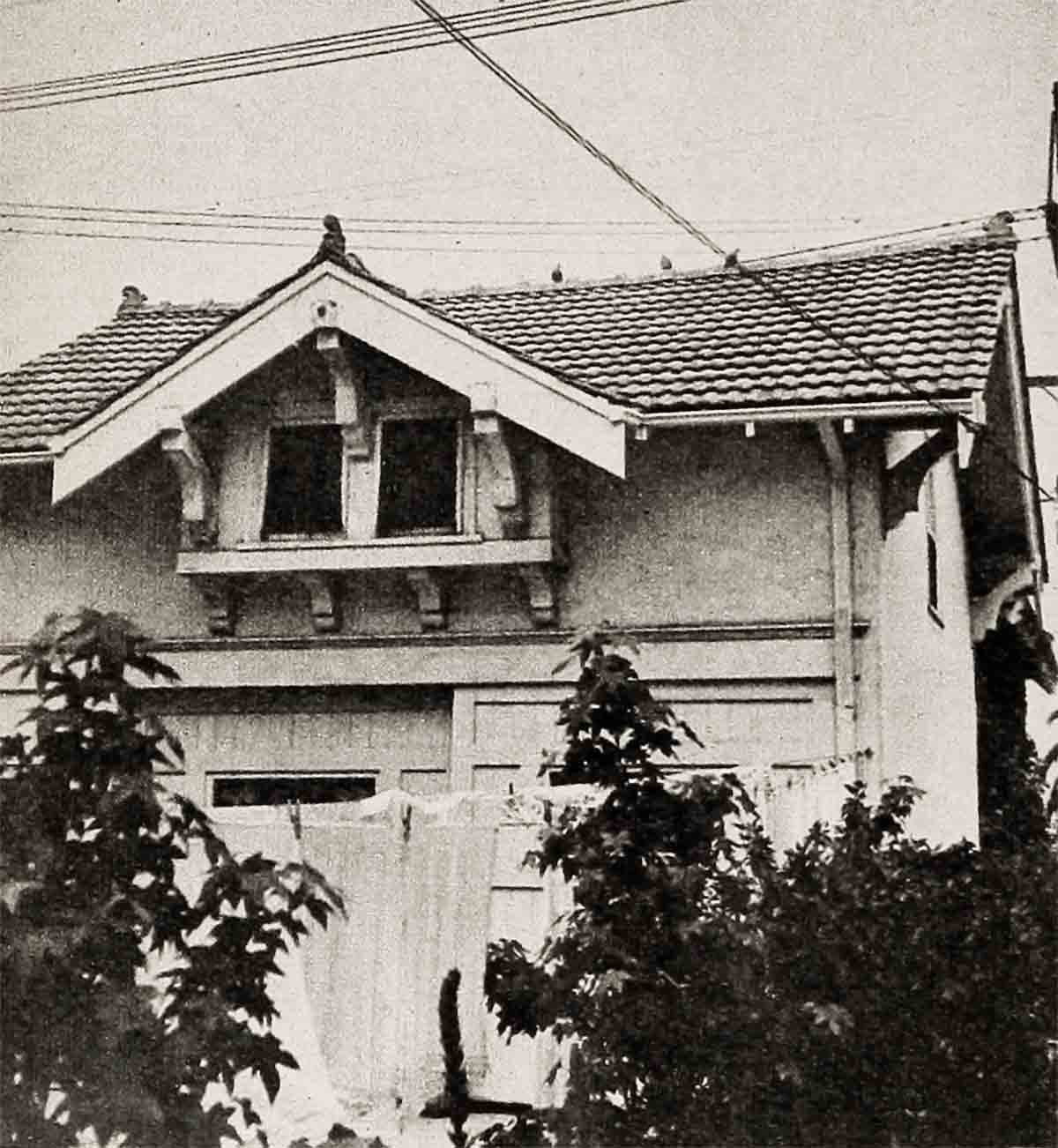

Tita took up the story: “We were in real trouble; we were entering on what we call our abject misery period. We were living in a garage on Berendo Street which cost thirty dollars a month, but that was an unreasonable amount considering our lack of cash. Sometimes we had ten dollars a week for food, but the time came when food became a matter of luck. We had a bed, two chairs, cold water only, no refrigerator. There was.no insulation and in August the heat was indescribable. I was expecting a baby—our first. I lived in one dress and Edmund had one good shirt which I washed out every night.”

“Americans we’d meet would ask us to dinner or slip a ten-dollar bill in my coat pocket along with words of encouragement,” Purdom said. “There was always something in view but the timing was bad. Timing is so important, not only in acting but in being available for opportunities when they are offered. You feel sure you can make good if you get the chance, but in my case so many things were contingent on opportunity timings. Our visa was running out and we were terrified of being deported. If you’re sent out of the country it’s almost impossible to get back in. We were conscious, too, of how our parents were worrying. Either Tita’s parents or mine would gladly have helped but they were not allowed to send money into a dollar country.”

“We couldn’t go to a clinic when it was time for the baby to be born,” said Tita, “because we were here on temporary stay. I’ll never forget Millie Gusse’s face when I asked her where the charity hospital was located. Millie has been one of our most faithful friends from the day we met her. She was casting director at UniversalInternational. She was horrified at the idea of my having a baby under such circumstances, so she arranged to have her brother-in-law, Dr. James Winsberg, see me. He was wonderful and kept me supplied with pills and vitamins and things and told me he’d deliver the baby without fee since my father and brother both were doctors. Millie tried so hard to get Edmund into U-I and when that didn’t work out she introduced him to Paul Gregory and to some TV people who were casting. She gave us all the clothes for the baby—blankets and everything. She has the greatest heart in the world.”

“Then when Tita was due for the hospital I got a job in Julius Caesar,” Edmund told me. “A small part—two days’ work. I had to stab James Mason and say, ‘I am sorry, my lord.’ That’s as close as I ever got to him. That day I hitch-hiked a ride to Twentieth to check on a part in Titanic. Nothing was decided, so I started walking to Culver City. I was so nervous Id be late that I ran half the way. But I got the part and I immediately borrowed $150 advance from my agent Paul Small and went right over to the Culver City Hospital and arranged for Tita to enter. The night Lilan—we call her Mrs. Doody—was born, I walked over there to see her.

“Strange things happen when you’re in trouble. I remember once we were evicted for non-payment of rent. Liz Fielding appeared out of nowhere and took us to live with her. She was like the hand of God.

“Another time when I was up for the part of Mr. Lightoller in Titanic, I had little hope since they turned me down on a contract. But I held onto that one-in-a-million chance. I waited and waited, but no word. It seems everyone knew I had the part but they thought I had been told and through some oversight neglected to tell me. We were going around in circles. We couldn’t go home, we didn’t have any money. Our parents were worried—they were slowly going out of their minds. Then we heard the good news.

“In another desperate moment I put an advertisement in a local paper to sell my gramophone equipment so we could eat. Then in the mail came a check for $100 from another American who insists on not being named. He merely told us to use it and pay it back when we could. Those were the wonderful things.”

When Tita Purdom went into the hospital on that $150 advance, she could stay only three days.

“Then back to the garage,” she said. “I was up washing diapers and dishes and everything else the day after they brought me home. There was an old two-burner stove but only one burner and the oven worked. Fortunately I breast-fed the baby because, having no refrigerator—not even an old ice chest—we had no way to keep milk in summer weather. But my brother, who is a doctor, used to work in the East End of London and made a discovery that’s practically infallible. Children who have been breast-fed for at least three months seldom get infantile paralysis. It isn’t proven, but statistics indicate it.”

Right after Titanic, Edmund got his contract at Metro and they moved into a little apartment above the Sunset Strip. He was still getting $350 a week when he went to Twentieth as the star of The Egyptian.

Others who helped them were Sidonie Espero and John Steel. When the worst was over they ran into Linda Christian and Ty Power. “I went to school with Linda in Palestine,” Tita told me. “When Edmund was set in Titanic, they took us on a trip to Mexico and when we returned we stayed in the guest room at their house until we got a larger place. We were expecting another baby in July, our apartment lease was up and we had to have more room. The day we moved our things were carried over in the bureau drawers from Linda’s; we had no suitcases and no luggage left.”

Purdom was secure by the time they moved into the comfortable three-bedroom house in Beverly Hills they now occupy. “Ty Power’s business agent found the house for us,” Tita said, “and we had to move in on Sunday since I was unable to help and it was the only day Edmund had free. He had to be at the studio early Monday morning for make-up tests. We couldn’t get a moving van so Edmund and Alabam Davis, his stand-in, and John Bryant, another friend who had been splendid through it all, made the move themselves.”

This new star with the strange up-and-down history is a genius at electronics; he has assembled his own high fidelity equipment and built one for the Tyrone Powers. He is probably the one person who could pick up Mario Lanza’s sound track and complete a polished and inspired performance. His father is an authority on Shakespeare, and a well-known drama critic and author in England. Charles B. Purdom is now working on books about Bernard Shaw and Harley Granville Barker. His father objected to Edmund’s acting ambitions because he believed his talent for electronics could give him ‘a more substantial life. Edmund was born Edmund Anthony Cutlar Purdom and hung onto the first and last names in spite of our best efforts to call him Edmund York. He was born at Welwyn Garden City near London and raised in a Benedictine monastery where the rugged routine included ice cold showers even on winter mornings. He attributes much of his freedom from colds to this Spartan beginning. He earned his first money by delivering newspapers. At nineteen he went into the theatre. He was in England’s Bedfordshire and Hartfordshire Regiments in World War II but was later transferred to the entertainment division. He is not yet thirty and has a long movie future before him. Metro has a long list of big productions lined up for him including The Prodigal and Ben Hur after Athena.

His wife Tita was born Anita Mary Esther Phillips. She’s half English and half Swedish but was born in France. Her father, who died last year, was once a physician to the Sultan of Johore. She traveled extensively when he was in the English Colonial Service. She is a ballerina, having joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet during the war. She has done both legitimate stage work and cinema in England and has played one part in Hollywood, a Cockney maid.

Being bitterly poor is no fun anywhere. But in Hollywood where life is glossy and luxurious, where there are more long cars and swimming pools than people, where even the dogs have their own beauty parlors, it’s cruel indeed. Edmund Purdom walked from one casting office to another until the soles were out of his shoes and often had a full meal only when some thoughtful person invited him an his wife home for dinner.

“When I think back on how we literally clawed our way into a desperate survival,” he told me, “how we had to beg and borrow and go without—I wonder how we came through it. At the time we accepted it and made the best of it from day to day. Looking back, it seems as unreal as a nightmare and I hope it will fade from our minds as quickly as dreams do.”

But the sour side of stardom has already reared its ugly head. Among the fan letters have been many roundly abusing him foe daring to take over the Mario Lanza role.

After news of his increase in salary was printed, he had to have the gearshift of his English car repaired. He located the salesman, who told him the cost should come around $100 or $125 at the most and told him where to go. But the car came back with a $530 bill. “Worst of all,” he fumed in telling the story, “the thing worked only in one gear.”

I talked with Millie Gusse, their good angel. She had been to an auction with Tita Purdom the night before and tells me she sees a great deal of them. She tried hard to sell Purdom to U-I. It’s amazing how many studios missed the boat.

“You know the boy now, Hedda, and you know he would attract anybody who looked at him,” she said. But when I told her that the Purdoms had enumerated all the things she had done for them, she tossed it off with: “All I want in exchange is the baby, Mrs. Doody, but they won’t give her to me. When you meet her, you’ll want her, too.”

Tita fascinates everyone who meets her. “She was five months pregnant when I met her,” Millie told me, “and she still hadn’t been to a doctor. She has amazing courage and she asked me quite casually where the charity hospital was. I nearly fell down. You don’t permit this. So I sent her to my brother-in-law who is an obstetrician and she was in good hands. He delivered the second daughter on July 9—nice, isn’t it?” Millie Gusse thinks Tita is terrific as an actress. “She’s a young Gracie Fields,” was her summing up of Tita’s performance in Man In The Attic, which she did between babies.

Tita Purdom has a professional career of her own if she wants it after the little family is all straightened out. While she was living with Liz Fielding she had her nose bobbed. Liz drove her back and forth to Long Beach during the ordeal. It was her husband’s first present to Tita after he got his MGM contract.

Some of Edmund’s friends think his temperament may get in the way of his progress. He’s a nervous fellow; quick, highly intelligent, with strong likes and dislikes. He admits he is thoughtless. “I never remember birthdays or anniversaries, my own included. And I don’t like imposing my birthdays on other people.” Others hint at a tremendous ego. From what I have seen of his work I feel it’s justified. Those who know them both say they have never seen so much courage in any two people. They faced the facts with no gripes, and that’s what attracted so many people to them.

THE END

—BY HEDDA HOPPER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1954