Pretty-Eyed Bébé—Leslie Caron

In the late spring of 1950, a blasé young man behind the soda fountain of New York’s La Guardia Airport found himself confronted by a wide-eyed young girl. “Eef you please,” she said, “I would like some of your ice creams.” She twirled the seat of the stool with an experimental finger, looked down the long expanse of shining counter and sighed, “I theenk a ba-nana spleet.”

To the soda jerk the French accent was no novelty—he was accustomed to dialects—but there was something about the girl that made it difficult to take his eyes off her. She was So intense, so earnest, and when she looked at him it wasn’t in an offhand manner, it was a direct gaze from chalk-blue eyes, tilted at the corners, that made him wonder if she wanted to start a conversation. But at the same time he had the feeling that if he did speak, she would bolt and run in fright.

Those who’ve seen An American In Paris, were left with the same impression of Leslie Caron. She is like a fawn, her eyes seem to listen as well as see, and her lithe young body is still and intent one moment, and then suddenly moving with swift grace.

That “ba-nana spleet” was Leslie’s first plunge into American ice cream. It was the way she chose to spend the 20 minutes allowed her in New York before changing planes for Hollywood, and the reason behind it was that her mother hails from Topeka, Kansas. Margaret Petit Caron had spent many a charmed hour describing America to her young daughter. Often Leslie would sit by her mother’s bedside in the early morning, talking for hours about the land of skyscrapers and Indians and mechanical things and the beautiful hair of the American girls. To Leslie it was like a fairy tale, but the thing that fascinated her most was the American soda fountain.

Leslie has been introduced, in the past year and a half, to a great deal more than our ice cream. She was uprooted from all the things dear and familiar to her in France and transported to Hollywood in an immense plane, then plummeted into the pink-and-white world of the movies. She improved her English, dated men for the first time, studied dramatics, visited her first nightclub, and starred opposite Gene Kelly in a film that turned out to be a masterpiece. She met and married George Hormel, heir to the Hormel meat fortune, and with the release of the movie became the toast of America as well as France. Yet Leslie feels she has not accomplished much since arriving in America. “I have no time for books, no time for attending the concerts,” she says, “and that is bad.”

Self-education is a driving force with Leslie, for although her schooling in a French convent. was probably superior to that given a great many of the world’s children, she feels that travel and music and books are the things that teach life, rather than geography and algebra. She is unaware that already, with only 20 years of life behind her, she is a cosmopolite who charms cynics right out of their boredom.

Margaret Petit, her mother, left Kansas to study dancing and eventually became the premiere danseuse of the Greenwich Follies on Broadway. Her health broke under the strain and in order to rest she went to Paris, intending to paint. It was there she met and married Claude Caron, a manufacturer’s chemist. Their first child was a son, Aimery. Leslie arrived little more than a year later. They grew up in the hilltop home of their grandparents in Neuilly, a suburb lying northwest of old Paris. Aimery, as big brother, was expected to watch over Leslie. He reacted to this responsibility by promptly introducing her to his friends, who accepted Leslie as one of the gang and expected her to do anything they could do. This included hanging on for dear life to a board set on roller skates which, laden with as many kids as it would hold, hurtled down from the top of a hill through the winding streets. Then there was the tree house, built by Aimery and Leslie, whose roof was formerly the lid of the family washing machine. The lid was sorely missed, but because the tree house was out of reach of everyone but the two children, no one ever found it. The attic of the family home yielded a small stove which the children hoisted into the tree and used to make pancakes. Later they found an old victrola, which was likewise stowed in the tree, and Leslie and her brother dreamed away many an afternoon listening to Chopin and Brahms.

Eventually, Aimery was sent away to boarding school, and his absence would have left a great void in Leslie’s life, if she hadn’t become interested in ballet. She was 11 at the time, and she accompanied a friend to a ballet class. Leslie sat quietly watching, wholly fascinated, then went home and announced, “I want to become a dancer.”

Margaret Caron pleaded with her. “I have always said you could choose your life. You can be anything you like—an actress, a painter, a nurse—but please, don’t be a dancer. It’s the most difficult work in the world. It will break your health. You don’t realize the hardship—”

“But I want to be a dancer,” said Leslie in a firm but faraway voice.

She began with one lesson a week, increased it to two, then three. When she was 14 she saw a professional ballet for the first time and came home with stars in her eyes. “I never dreamed it was so beautiful,” she said. “All the lights, the music, the costumes—”

“Well,” said her mother, sounding very much like Topeka, Kansas, “I suppose that’s that. We’ll take you out of the convent. If you’re to be a dancer, you must devote your life to it. You can study at the National Conservatory.”

Claude Caron’s parents were horrified. The French Catholic church frowns on dancers, and despite the popularity of ballet in France, to the Caron family it was comparable with the devil himself. Leslie’s mother flew to her aid. “We haven’t much money,” she pointed out. “We can’t give Leslie the advantages of high society. Nothing would be so dull for her as a routine education and a routine office job. If she wants to live life, she is better off in the ballet.” She smiled to herself and added, “In show business.”

With her -mother by her side, Leslie went on and upward like a balloon caught by the wind. The war was over and the liberation of France was complete. In the past years, the family had left Neuilly to go to the south of France for a year in 1939. They returned to live on the Left Bank during the war, sent the children to Cannes during the occupation, and now all were happily settled back in Paris near the Place d’Etoile. When Leslie was 15 she joined the Ballet des Champs Elysees and soon had a bit part all her own. Her first solo performance, a dance that left her alone on the stage for 30 seconds, was given on a night when the theater was crammed with celebrities and royalty. Leslie was dressed as a clown, her face covered by a mask, and during the first ten seconds she made what to a ballerina is a disastrous error. From a difficult step she landed in the wrong position—perhaps two degrees off. Says Leslie now, “I think to myself, I miss it. scream. I better walk out. But the music goes on and I think I better stay. Afterward people applaud like—how you say—like mad—and I think they are mad, perhaps. Or there is someone else on the stage. But no, it is for me. My mother, she comes backstage afterward and says ‘You were very good, darling’. I do not understand. I have made a most awful meestake.”

However unforgivable Leslie herself considered it, it didn’t seem to matter to anyone else, for soon she was on tour and doing the same solo bit part before the King and Queen of Egypt. Lebanon followed, then Greece, where the company danced for the Queen. Because Leslie was the youngest of the troupe, she was chosen to present flowers to the Queen. The very thought petrified her. “There I am so very nervous, and here comes the Queen with her pretty children. She is very gracious and presents me the children. I do not know quite what to do so I bow” (rhymes with low) “and then the little prince extends me his hand. I am so very stupid and I bow again before I am sensible enough to take the child’s hand.”

That faux pas didn’t seem to bother anyone but Leslie, either, and soon there was a special ballet written for her, “Oedipus and the Sphinx.” It was during the Paris season following the tour that Gene Kelly attended the Ballet des Champs Elysees and was struck with Leslie’s talent. He went backstage after the performance to congratulate her, but Leslie had gone home. She had knows he was in the audience that night—it was common knowledge via the backstage grapevine—but had no thought that he would want to see her. It is doubtful she would have stayed even if she had known, for at this point Leslie’s great success was the talk of all Paris and she was perpetually swamped with compliments, congratulations and the adoration of the public. She was only 16 and found the adulation too much to bear in comfort. Some people are so constructed that they can listen to praise from sunrise till sunset and lap it up with ease, but to Leslie if was as though she was being pushed and jostled with the unceasing acclaim. Even her family could talk of nothing else once she was home, and this included her father’s family who, once Leslie’s name appeared in the tiniest print on a pro-gramme, had turned completely human and considered the ballet the greatest thing that ever happened to France, and Leslie the greatest thing that ever happened to ballet. The plaudits kept pouring in, building up pressure, and Leslie wished desperately she could be just a plain human being once more, sitting in the tree house and listening to music.

Her negative reaction was possibly due to her health which, as her mother had prophesied, was breaking under the strain. There had been little to eat in France during the war, during those years when Leslie was growing so fast and needed nourishment. There had been little meat, milk or eggs and only squash had been fairly plentiful. But people can’t grow healthy, or particularly happy for that matter, on a diet of squash, and Leslie developed anemia, which became more serious as she pursued her strenuous career. Of necessity she stopped working for a whole year, but never once in all that time did she even think of leaving the ballet. Back with the company she went on tour through Holland, Belgium and England, where a command appearance was made before the Queen and Princess Margaret Rose. For the latter performance Leslie was honored by having her act included in the chosen four out of the possible 20. She was as excited as anyone else, for the French people feel a close alliance with English royalty, and before the performance began ie was flat on the floor of the stage along with 39 other girls in the cast, lifting the heavy fringe at the bottom of the curtain in order to see the Queen and Princess in their box. Excitement got the better of them and they soon became so obvious that the Queen noticed the line of faces, whereupon she smiled and waved to them.

It was the high spot in Leslie’s young life until the spring of 1950, when Gene Kelly again came to Paris to find a leading lady for An American In Paris. He a girl who could dance, act and speak a bit of English, and like a homing pigeon he went straight to the Ballet des Champs Elysees.

First he interviewed Leslie at his hotel and gave her a scene to study, then arranged a screen test which was flown back to Hollywood. “Don’t count on it,” he told her. “These things take time. There is only a chance you’ll be chosen.”

Leslie went home with mixed reactions. She didn’t want to leave the ballet. It was fun, traveling around the world with the troupe. But the doctor had said her health would not stand the strain of dancing year in and year out. Because of this she had given a thought to movies—French movies—and had even taken some tests, although, as yet, nothing had come of them. But there was America to consider, too. Ever since she’s been a little girl it was always, “when we go to America—”

Weeks passed and Leslie almost forgot about it. Then, the day before a new show opened, Gene Kelly telephoned her. It was all set, he said. His studio was so enthusiastic that a contract had already been drawn up. “You’ll have to pack right away,” he said. “You’ll leave in three days.”

“So then,” says Leslie, “I am so excited I jump on my head!” She went home to the family and they almost collapsed at the news. “But should I go?” Leslie wanted to know.

“Should you go!” they howled in unison. “Of course!”

There was frantic packing, and hurried farewells. Leslie said goodbye to her friends in the ballet, kissing them on the cheek three times as was the custom. It seemed no time at all before she and her mother boarded the plane, and they left France without even knowing if the French moviemakers had decided that Mademoiselle Caron was worthy of a contract. The plane’s sleeping accommodations were wasted on Leslie. She sat by the window and looked until her eyes felt they were being pulled from their sockets. England, Ireland, Newfoundland, the soda fountain in Manhattan, a stop at Chicago, and they were on their last hop to Hollywood.

The day after she arrived in Hollywood, she was invited to Gene Kelly’s home, where she met his family and many people with whom she would work. Leslie was terrified and stood in a corner as often as possible. It seemed people were staring at her “with beeg eyes” and momentarily she wanted to be back in France, where everyone was nota stranger. She had little time to be homesick, however, for the next day she was introduced to all the important men at MGM and, although her hands were clammy and her heart going like a pom-pom gun, she managed to read aloud from the English script they handed her.

Mrs. Caron returned to France, where she and Claude Caron sold their home and went back to the Virgin Islands to live. Aimery went on to Hollywood, to share an apartment with his sister. With Aimery near, plus the passage of time, Leslie learned there was nothing to fear in Hollywood, that its people were warm and friendly, and she began working with enthusiasm. For two months she rehearsed dances every day and studied English on the side. Today she has perfected the language to the point where she pronounces even Paris the way we do, rather than retain the French pronunciation. She explains this is necessary, for if she lets one French word or inflection slip into her conversation, she lapses entirely into her native tongue.

She turned 19 in July of 1950 and soon was dating men for the first time. She had had many admirers in France, but ballerinas are a very close group, seldom going with outsiders, so that at home she had had no opportunity for romance. And because it is not proper for young French girls to visit Paris night clubs or even sidewalk cafes, Hollywood’s night clubs were the first thing of their kind that Leslie had seen. Aimery watched his sister emerging from her cocoon and teased her about it in the evenings when she was cooking their dinner. In Paris, Aimery’s friends had formed a pool, with a case of wine going to the boy who would give Leslie her first kiss. The wine was never collected, and in America, George Hormel came along before Hollywood’s bachelors had much time for beginning the wine-winning project.

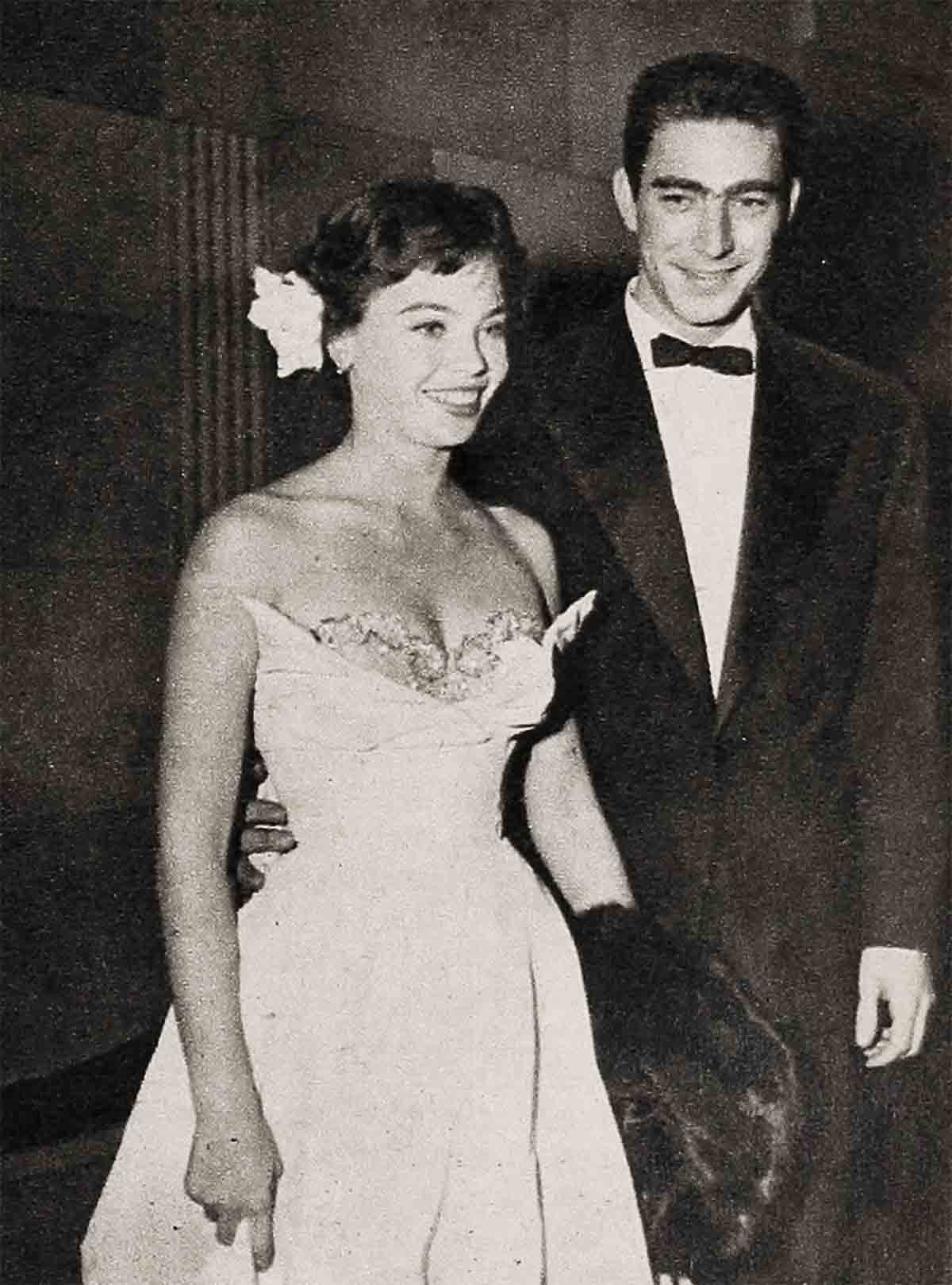

They met briefly at a cocktail party and young George was immediately attracted to Leslie. She noticed him for only one reason. “He has one eyebrow, you know,” she says. “Very funnee.” We understand this to mean that George Hormel has all the eyebrows necessary to a human being, but that there is not the usual absence above the bridge of the nose.

Not long after their first meeting, Leslie was planning to have dinner with two other girls, one of whom had a date with Jimmy Hormel, George’s brother. These two were going to see Ella Logan afterward at the Greek Theater, while Leslie and the other girl friend were to follow the dinner with a concert at the Hollywood Bowl. But that afternoon George happened to ask his brother about his plans and Jimmy told him he was meeting some friends for dinner. “Who’ll be there?” George wanted to know.

“Among others,” said Jimmy, “Leslie Caron. At least, for dinner.”

“Who’s she?” George wanted to know.

“What a memory! You almost melted over her the other night at the cocktail party.”

“That girl!” Yelled George. “Wait for me!”

He went to dinner with them and talked the girls into accompanying the rest of them to the Greek Theater. By adroit maneuvering he managed to sit next to Leslie, and Miss Logan’s talents that. night were wasted on George. After the show they went to Ella Logan’s home, where she was charmed by Leslie and asked for her phone number. And Leslie, throwing shyness to the winds, answered in clarion tones.

“Sure I say eet loud,” she says now. “I think this Geordie is pretty cute. Veree cute, in fact.”

George Hormel used his head as well as his ears and phoned Leslie for dinner the next day. He proposed to her, before the soup was served, in French.

“Geordie is veree funnee,” she explains. “He proposes in French because he knows he has such a cute English accent. Geordie,” she adds, “he is funnee all over.”

Leslie replied that evening that Mr. Hormel must be out of his mind—that he hardly knew her. He knew very little, in fact, other than that he loved her. A week went by, during which they dined together every night, before he learned he had been wrong in thinking she worked as an extra in movies. At the end of that week he asked if she would fly with him to his family’s home in Austin, Minnesota. The trip, the chance to see more of America, may have appealed in part to Leslie, but after-seven dinner dates she was more than willing to spend time with George. His parents (his mother is French-born) found her captivating and she was equally impressed with them, but Leslie returned to Hollywood without a decision. Her mind was made up for her on September 22 when the studio handed her a script and told her she would begin work almost immediately on MGM’s Glory Alley with Ralph Meeker. She was due to go to San Francisco on Monday for the opening of An American In Paris, then to Florida for a publicity matter, then to begin working on the new picture on her return to Hollywood. That afternoon she told George, realizing they couldn’t possibly be married for three months.

“That makes it simple,” said George. “Let’s get married tonight.”

They bought a wedding ring just before the stores closed and phoned an airline for reservations to Las Vegas. George phoned his two brothers, then Aimery. “What’re you doing tonight?”

“You have a party, yes?” asked Aimery.

“Well, sort of,” grinned George. His mother was visiting Hollywood at the time and when Leslie and George had rounded up Mrs. Hormel and the three brothers, everybody was hysterical. Particularly Aimery, who knew little about the romance and couldn’t believe his kid sister was actually altar-bound.

They arrived in Las Vegas at four o’clock on Sunday morning, and everyone headed for the hotel except Leslie and George, who took off to get their license. Finding the bureau closed, they took a taxi to get breakfast, inviting the driver to join them. The license acquired, they made an appointment with a minister for six-thirty A.M., then went to collect the family. The ceremony, replete with organ music (Bach, requested by Leslie, granted) sent both the older and newer Mesdames Hormel into tears. George wired his father in Minnesota, “YOU HAVE JUST BECOME THE FATHER OF A HUNDRED AND TEN POUND GIRL,” and Leslie wired her parents in the Virgin Islands that she had changed her name, and they all flew back to Hollywood, the newlyweds speechless with happiness.

After a harried honeymoon in San Francisco and Florida, and a visit to the Virgin Islands to see Leslie’s parents, they settled down in a rented house in Laurel Canyon, filled with furniture, including a piano, from George’s bachelor apartment. For George plays hot piano, and has temporarily resigned his job with the Hormel Company in order to study, and make jazz recordings.

Leslie appreciates his talent—she likes the rhythm and spontaneity of jazz—and often dances as he plays. Once in a while she’ll spin a record of her own, and when George makes a face at Bach, Leslie smiles in a very grown up way and tells him that one day he will learn to love it, because it is a part of her.

She wants to return to Paris only to show her city to George. In the beginning she missed France but now she loves it, here, loves the country and the people. And the American people love her. They are—how you say—enchanté.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1952