Esther Williams and the Blind Children

“God bless you, Miss Williams,” the woman said softly. Her cheeks were wet with tears. “God bless you—”

Esther, tall in her high heels, tried to smile down at her and found herself blushing. “Please,” she said, “I haven’t really—” she reached out a hand to the woman.

And to her intense surprise, the woman seized it and raised it suddenly to her lips. Before Esther could move, she had kissed her hand—and turned and fled.

And Esther stood staring after her, with the tears beginning to well up in her own eyes.

She was still standing there, motionless, when she felt a hand tug at her skirt. She looked down, and a little girl was beside her—a chubby child with brown braids and a small, shy smile.

“Miss Willyum—now Mommy’s gone, will you take me back? I want to change into my swimsuit, all right?”

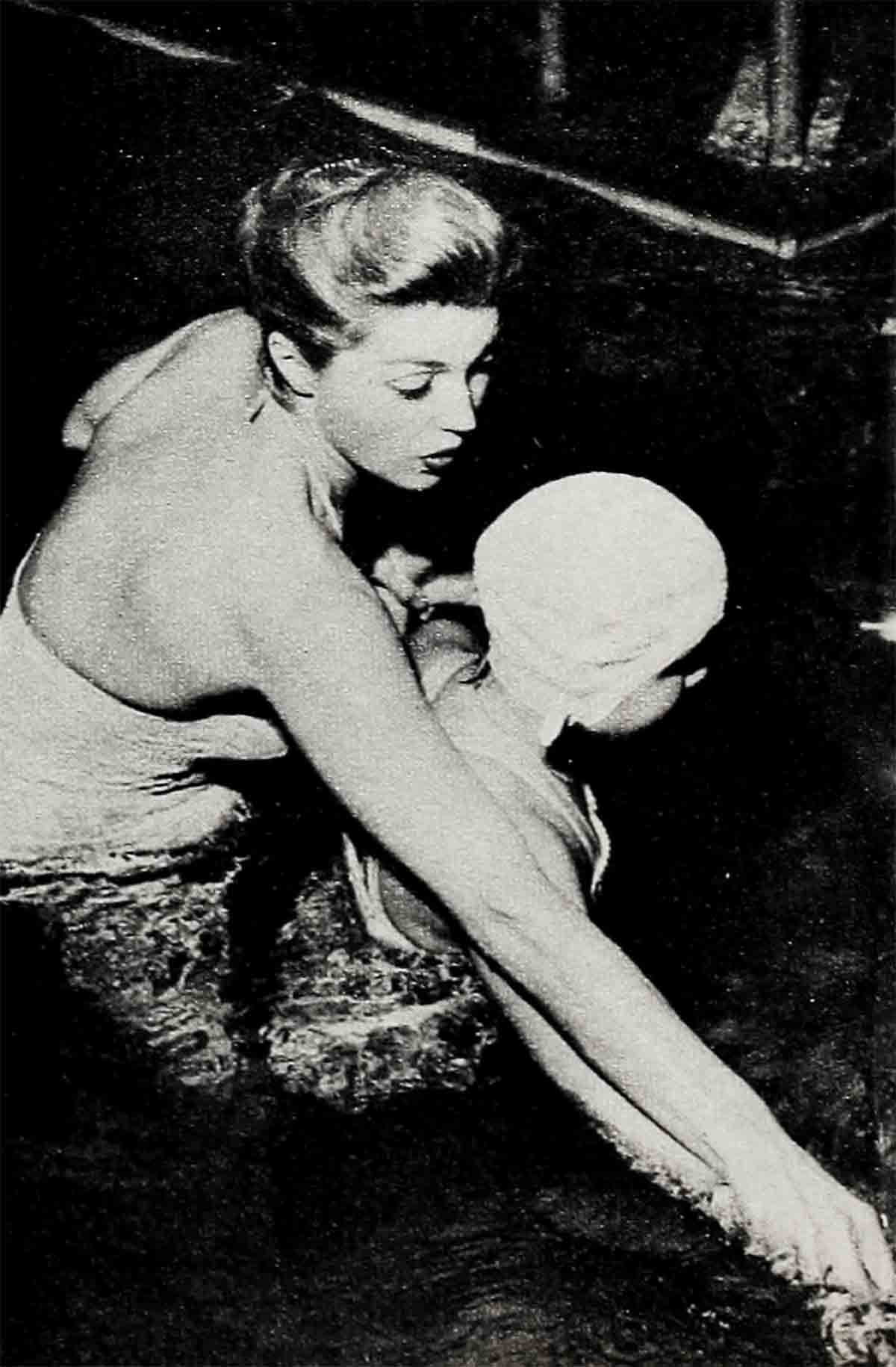

“Of course it’s all right,” Es said. The tears disappeared as rapidly as they had come. With one hand she brushed a loose lock of hair from her forehead. With the other she reached for the child’s fingers, took them firmly in her own.

“We’ll go across the grass,” Es said. “In about ten giant steps we’ll come to the curb—don’t forget it, now.”

“I won’t forget,” the child said. “I hardly ever fall over anything any more.”

She got no reply. For Esther Williams, walking hand in hand with the child across the sunlit lawn of the school, was repeating silently a prayer—a prayer she had said once, years ago, and never forgotten. A prayer she repeated now, a hundred times daily: Lord, guide this baby’s steps. Let her never fall, if that is Your Will—but if she does stumble, Lord give her the strength to pick herself up and start to walk again. . . .”

For the child who walked so confidently by Esther’s side—was blind.

And only months ago, only a few short months before, she had not walked this way, head up, lips smiling. She had tottered instead, staggering on unsure little feet, her arms stretched out before her, feeling for walls that she could not see, for people that she should not bump into. She had fallen then once for every few steps she took, and her voice was a whimper of pain, of confusion, of loneliness. Her life at seven years, was one long groping in the dark—a dark in which she could not begin to dress herself, to eat alone, to play.

She had never seen. She would never be able to see, And it had seemed then, when her mother brought her to the school, that in the deepest sense, she would never be able to live.

Esther, seeing her for the first time, had stood stock still in the room. She had whispered to her friend, Merle Loft, who stood beside her, “Do you remember? Do you remember when—”

And Merle had nodded.

They both remembered—remembered when so many children in the school had looked like this one. Had it been so long ago? It seemed, in the presence of this child, as if it were yesterday. And yet—it had been several years.

Calling for help

The school was asking for aid then, as it was so often forced to do. A national sorority, Delta Gamma, had begun it, had taken in three blind children who came every day to learn to exist in their black world. That was in 1938. By 1949 there were not only more day students, but six resident pupils, a Cradle Club of twelve blind babies—and a waiting list that seemed to stretch on and on forever with no money to support it. Harold Lloyd, the great star of silent movies, heard about their plight and threw his home open for a benefit for the school. Esther Williams was one of the stars who came to take her bow, to put her arm around one of the school’s children, to give her check—just as others did.

But there was something special about Esther then.

She was going to have a baby of her own.

A baby who might, if God willed it, be born blind.

Two months later, in a quiet hospital room, a nurse bent over Esther to say, “Mrs. Gage—you have a son.”

Esther opened her eyes.

And in that split second, there flashed across her mind a memory—a memory of a wan little face, a motionless body, a pair of unseeing childish eyes. . . .

“A beautiful, perfect, healthy little boy,” the nurse said now, to Esther Williams.

She smiled. She closed her eyes again. God had been good to her. God would go on being good. And she would repay him if she might, by ministering to the children of other mothers—who had not been so lucky.

A purpose

She had planned a long rest after Benjy’s birth, a time to play with her baby, laze around in the sun, swim to her heart’s content, think of nothing. Now her free time had another purpose. She owed it to God.

Three weeks later she walked across the lawn of the school for the first time. And came across five children, sitting op a grassy bit of ground, silent, motionless.

“It’s a play period,” Merle Loft, the school’s director of education explained softly. “Other children would be chasing butterflies, playing tag—but these children are new here. They’ve been protected so much at home—parents are afraid, quite naturally, that they will hurt themselves if they’re too active They come to us almost afraid to move. It takes time—sometimes a lot of time.”

Esther thought of Benjy at home, wriggling his plump healthy body, beginning already to smile, to turn his head for a noise, a new sight. Her heart turned over inside her.

“Why are these little ones so thin?” she whispered, “don’t they get enough to eat?”

Merle shook her head. “There’s plenty of food. But the children who are born blind don’t know how to eat it. Chewing isn’t instinctive, like sucking, Miss Williams. A baby learns it from watching its parents. These children—the children born blind—don’t even know how to eat. They have to learn everything—right from the beginning. laugh. To get along in the world.”

The gift

“I came to bring you money,” Es said softly. Her eyes traveled slowly across the solemn little faces. “Now I have something else to offer you as well. Please—would you let me teach them to swim?”

Merle stared at her for a long moment. Then she wet her lips. “Oh, Miss Williams,” she said, “if you only would.”

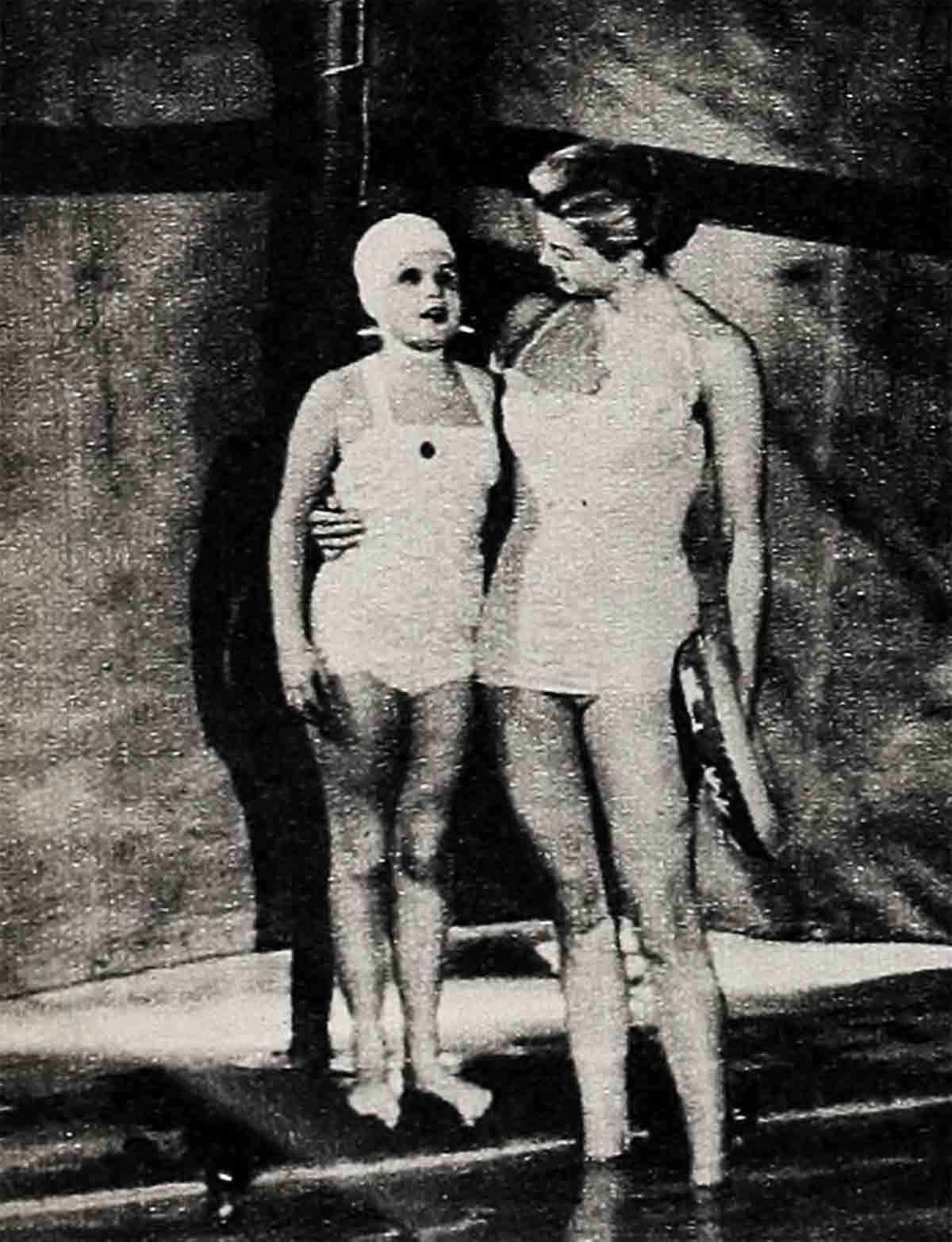

That same afternoon, they had bundled half a dozen youngsters into Esther’s car. Towels and bathing suits, hastily dug up, cluttered the back seat. An hour later, in the Chase Hotel swimming pool, the water carefully heated to just the right temperature to cradle a thin little body—Es held a blind child in her arms for the very first time.

And through sudden tears, she began her lesson.

For an hour, she introduced children who could scarcely walk to the water which would bear them up. She moved little arms, accustomed to hanging quiet for fear of breaking something, to the wide expanse of the swimming pool, where they could wave and reach and splash— and there was nothing to break. And she stretched her own strong arms out beneath them, to let them lie on the water for the first time in their lives, bury their faces in its depths.

And when the lesson was over, when the last child, rosy with unaccustomed exercise, had had his hair towled dry and combed into place, when the last suddenly excited, chattering baby had been helped back into her clothes, she turned to Merle and said, “I’ve taught children before. I’m going to teach my own. But I’ve never taught children like these—I don’t think I’ll ever find more like them. They take to water as if they were born to it. They’re not handicapped babies in this pool. They’re little gods.”

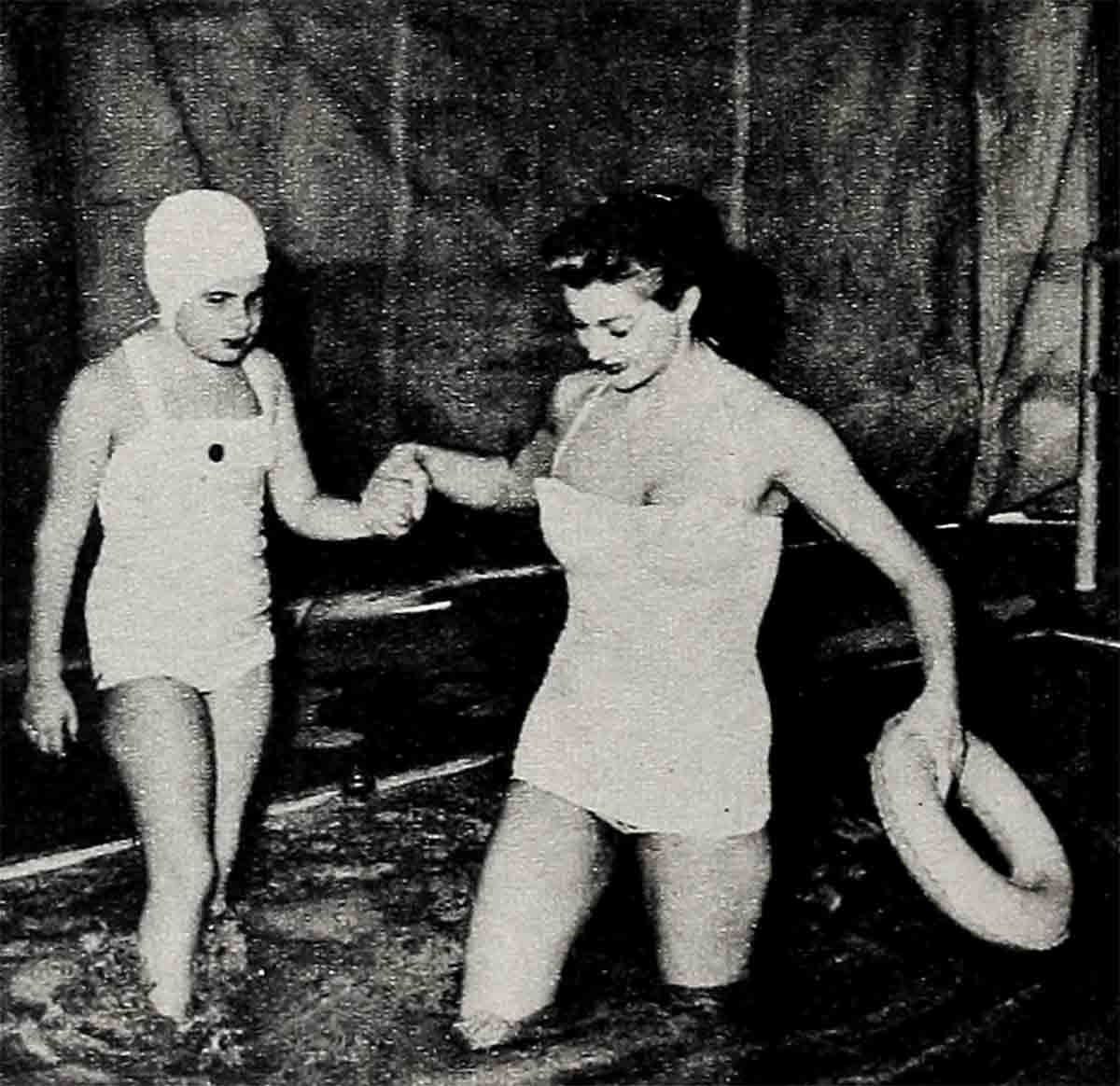

That was the beginning. Nine years ago. And for the children of the nursery school—it was also the end—the end of fear. What Esther had said in awe and wonder was true—they were born for the water. Their sensitive ears told them somehow how far or near the sides of the pool they were. Their high young voices, calling to each other in newfound pride, told them when other children were close. And their legs, grown strong with kicking the foam, learned more quickly to walk with strength and confidence on dry land.

Fun in the water

They learned to float, to dive, to do the back stroke and the dog paddle, the Australian crawl and the side stroke. They learned to bump into each other and ricochet off without tears. They learned to splash each other with mock fury and give back as good as they received.

They learned to laugh out loud.

And one afternoon, years later, when the children no longer swam at the hotel because Esther Williams had given them two pools on the school grounds a young father brought his four-year-old son to the school for the first time, and walked away from the swimming pool with fury on his face.

“I was told this was a school for blind children,” he snapped. “Those children in that pool aren’t blind!”

Merle Loft smiled at him. “Go back,” she advised. “Take a closer look at their faces.”

A minute later the man was back in her office, his son in his arms. “It’s a miracle,” he said, without any trace of joking in his voice. “Please—when can my son begin?”

A miracle, he had said. A miracle that these children were learning at last not only to swim but to eat, to dress themselves, to walk with firm steps in the world of sighted people. A miracle wrought with patience and love, with the help of educators and doctors and one tall movie star—a miracle of hope and of God.

A miracle that had reached out to the little girl who trotted so confidently beside Esther now, to her mother who had whispered, “God bless you—” and to another mother who had taken Esther’s hand as she stood beside the pool only a week before.

“Miss Williams,” that woman had said, “I want you to know, as far as I’m concerned—you’re a saint. A saint in the eyes of God. . . .”

THE END

You can soon see Esther in U-I’s RAW WIND IN EDEN.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1958