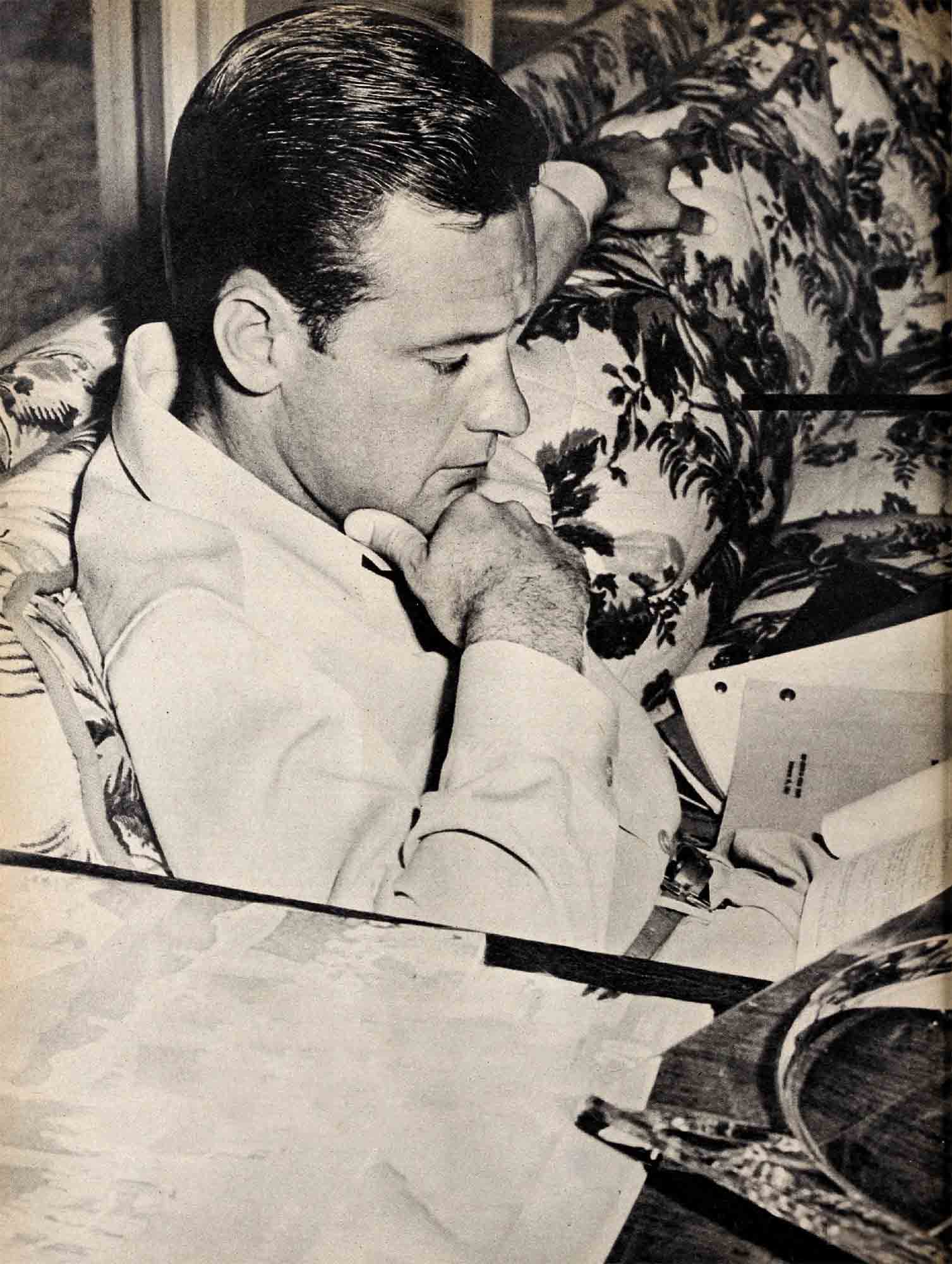

Mr. Dynamite—William Holden

Bill Holden is a nice unassuming guy. His family, his friends, his employers and his co-workers all vouch for this. They also vouch for the fact that he carries in his nature a high charge of emotional dynamite. Such a high charge that it is indeed fortunate this explosive element is under firm control.

In the beginning the control was imposed by Bill’s fond but strict parents. By the time he was old enough to make his own rules, it was as much a part of his nature as his talent and his rugged good looks.

Bill’s mother, Mrs. Mary Beedle, remembers the oldest of her three sons as an impulsive, enormously curious and eager little boy who, “Could think up more mischief in a minute than I could undo in a day.”

When the spirit of adventure was in him, he’d try anything—a parachute jump, for instance, with his mother’s umbrella from the roof of a fifteen-foot garage. Nothing but the umbrella was broken in this experiment, so experience could not be said to have taught him caution. Later he tried tight-rope walking on the telephone wires above the street.

Responsibility Bill learned the hard way by discovering very early in life that—in the Beedle family, at least—responsibility and self-discipline were the price of privilege.

When Bill was very young, the family shared the big, comfortable home in O’Fallon, Illinois, owned by his grandfather. And Grandfather’s rights to privacy and order had to be respected.

Bill’s mother was a schoolteacher. His father was a serious young chemist, driving himself at work to establish a business, needing a calm, quiet household when he came home from the office tired. Bill could invite all of his young friends to play at his house. They could pitch tents, build tree houses, or play cops and robbers to their hearts’ content—if they restricted their games to the play areas of the big, tree-shaded yard and stayed clear of Grandfather’s rose garden. Bill could make an unholy shambles of his room if he were willing to put it back in order.

By the time the family moved to Monrovia, California, when Bill was five, going on six, he knew enough of give and take to instruct his year-and-a-half-old brother, Bob, in the techniques of getting along in the big, new world they both were investigating.

AGE 12—his father’s illness turned him into the man of the house

AGE 21—in “Golden Boy” he was overnight sensation. But he wouldn’t play the social lion offstage

Not that, there weren’t occasional crises.

Mrs. Beedle remembers one eventful Sunday morning when Bill presented himself for breakfast in battered blue jeans and a beat-up shirt and announced that he was not going to Sunday School. He had a new bicycle, it was a beautiful day, and he could see no reason for cooping himself up indoors.

It was open rebellion, for Sunday School was a Beedle family “must.” But no battle ensued. All Mrs. Beedle did was to remind her son calmly of the inseparable link between privilege and responsibility. It would be okay to skip Sunday School if Bill were willing to give up the movies next Saturday.

He went to Sunday School.

Once, when he was ten, Bill nearly burst with excitement when Ray Schalk, the great catcher for the Chicago White Sox and a family friend, offered to take Bill out to the training field to watch a winter training session.

Bill was mad about baseball, and mad about Ray, and he wanted that day with the team more than he had ever wanted anything in his life.

And, in her heart, Mrs. Beedle wanted it for him. But she couldn’t weaken. For some time, Bill had been showing definite signs of being allergic to his school work. With his standing so questionable, a day’s absence would be a serious thing.

“But I may never get a chance like this again,” Bill stormed.

“I know,” said his mother, sympathetically. “It’s really too bad.”

“For a minute,” Mrs. Beedle recalls, “it looked as though he were going to cry. I don’t know what I would have done if he had. Given in, probably. But he just stood there looking at me, two big tears glistening in his eyes, then he walked over to the phone and called Ray Schalk.”

“Gee, Ray, I’m awful sorry,” she heard him say. “I’d give anything to go. But I’m in a jam at school and I can’t.”

The control already was operating. And he needed it soon enough. For in the early thirties the Beedles—along with the rest of the country—faced up to the problems of the depression. And Bill’s father, seriously ill of pneumo-silicosis, was bedridden for three years. Mrs. Beedle—with three small sons by this time, Richard having arrived two years after the family settled in California—had to go back to her teaching. Bill, as the oldest, actually stepped into his father’s shoes in the household.

Mrs. Beedle says she should have realized then that Bill was destined to be an actor. He played out his new role as though it were a part in a play. Many a night when his mother came wearily home from school, he would seat her at the table like a queen, and, appearing in white jacket, with a spotless linen towel over his I arm, proceed to serve her the dinner he had cooked, as though he were the majordomo at the Ritz.

To know these stories about Bill Holden as a boy makes it easier to understand the rare blend of temperament and talent, modesty and common sense which today sets him apart from most of his Hollywood contemporaries.

When Artie Jacobson, head of talent of Paramount studios, first set eyes on Bill, he was dumfounded by the earnest six- footer who sat across the desk from him.

Jacobson’s assistant had “covered” the performance at the Pasadena Community Playhouse to scout a young actress.

The assistant had come back raving, not about the girl, but about the “elderly character actor” who played her father.

The “elderly character actor” by virtue of wig, beard and grease paint, had been twenty-year-old Bill Beedle, a Pasadena Junior College student, making his very first appearance on any stage.

“Any green kid who can convince me that he is an old man is an actor,” the assistant had reported.

Jacobson offered Bill a chance any other twenty-year-old of his acquaintance would have jumped at—a screen test.

“We’ll shoot it Saturday,” Jacobson said, “provided you can get yourself over here every day between now and then for some coaching.”

Quite calmly Bill said that to get to the studio every day was out of the question. “You see, it’s finals week and I can’t skip classes.”

“You mean you’d pass up a chance like his rather than skip school for a week!”

“I can’t risk flunking out,” the boy said.

Artie threw his head back and laughed. “I think you’re crazy; I think I’m crazy, too. But I like you. Let’s do it your way.”

A series of coaching sessions for after-school hours were arranged, and the test was shot on schedule the following Saturday. (In the meantime, Bill passed his college exams with flying colors.)

However, a producer, who had final say about hiring new people, looked at Bill’s test, and yawned. Bill was nothing, he said. Dull, colorless.

Bill had everything, Jacobson insisted, he just didn’t throw it at you. It was a matter of restraint, rare in a kid so young.

At that moment, Mr. Biggest, Y. Frank Freeman, vice president and studio head of Paramount, walked into the projection room, and wondered out loud what the argument was about. Jacobson filled him in and re-ran the test.

Freeman lined up with Jacobson and gave the green light which put Bill Holden under stock contract—at a beginner’s quick $50 a week.

Not long after this William Perlberg, about to produce “Golden Boy” at Columbia, was looking for a girl to play the sister. He ran off a Paramount test of a starlet. It was Bill Holden’s test, as well.

When Perlberg looked at the test, however, he telephoned Artie in great excitement. “Who is that boy?” he yelled. Jacobson told him what he knew about his find.

“You’ve found our Golden Boy,” Perlberg told him.

Working gruelling hours daily in a strange new medium, dividing his nights between a violin teacher and a boxing coach who were teaching him the special skills the exacting part demanded, Bill was an overnight sensation in Hollywood. But he was too busy and too tired to know it. He did have time to make cne good and lasting friend. Hugh McMullan, a graduate of Williams and Oxford and a former teacher of music and art at Berkshire, was “Golden Boy’s” dialogue director.

McMullan chose books from his substantial library for Bill to read, helped him to an appreciation of music and art. “Made me,” says Bill, “appreciate many things I might otherwise have overlooked.”

One of those “things,” although it probably wouldn’t occur to Bill, was a beautiful young girl whom McMullan had known as Ardis Ankerson in New York, and who now—as Brenda Marshall, under contract to Warner Brothers, was starring in “The Sea Hawk.”

Bill and McMullan had taken a small house together in the Hollywood hills, and McMullan—seeing that Bill was singularly lacking in girl friends—undertook to fill that hole in his friend’s life, too.

One after another, pretty girls that McMullan knew were invited to the bachelor diggings for dinner. At some point during the evening Hugh would look questioningly at Bill, and more often than not be answered with a disinterested shrug of the shoulders.

It could have been, as McMullan thought, that Bill was too exhausted from his strenuous work at the studio to be interested in romance. But he wasn’t too exhausted to go to Artie Jacobson’s Saturday night badminton parties and play his heart out.

When McMullan first mentioned Ardis Ankerson, Bill was even more obstinate than usual.

“I don’t want to meet any married women with children,” he said. Ardis had separated from her husband, but, in Bill’s eyes, she was married.

However, soon after the release of “Golden Boy,” when Warner Brothers borrowed Bill to co-star with George Raft in “Invisible Stripes,” Hugh hinted again that Ardis was a mighty attractive gal and that Bill just might run into her on the lot.

“If you do,” he said, “invite her to dinner.”

They did meet. And Bill had found his “one woman” at last.

Bill and Brenda Marshall—he, and most of her intimate friends, still call her Ardis—met in September, 1939, and were married twenty-one months later, on July 13, 1941, in Las Vegas, Nevada.

It would have been much sooner except for the time involved in Ardis’ suit for divorce and custody of her young daughter, Virginia.

When they finally set a date, Bill was working. So they decided, since he was to be allowed no time off, to charter a plane for a Saturday night flight to Las Vegas. Bill arranged for the Congregational minister to meet them in his chapel at 10 p.m., and made reservations for the bridal suite and a midnight wedding supper at El Rancho Vegas.

To get things off to a hectic start. Bill—and his best man, Brian Donlevy—were held up for a couple of hours on the set. When their plane got off the ground, with the bridegroom still in full make-up, they ran into bad weather, landing finally, three hours late, in a muddy emergency field.

By the time they hiked into town it was three o’clock in the morning. The minister had gone to bed. And the hotel had given away the bridal suite.

At four, the pastor sleepily performed a ceremony at the foot of a big double bed in a hotel bedroom. After donning fresh clothes, the Holdens and the Donlevys felt gay enough for a champagne breakfast.

An hour later, their pilot suggested that they’d better head back to Los Angeles if they wanted to beat the fog to the Pass.

“That,” Bill sighs, “was only the beginning. On Monday I went back to work. Ardis moved our things into the new house we had bought for the honeymoon we didn’t have.”

On Wednesday, Ardis left for three weeks’ location in Canada. She returned on a Friday afternoon to find that Bill had left Friday morning for location in Carson City. Bill came back from Carson City ten days later in an ambulance, and was delivered to the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for an emergency appendectomy. His bride visited him there every day and told him how things were shaping up in the honeymoon house. On the day before Bill was to be released, Ardis complained of a pain in her side.

“Sympathetic pains,” Bill scoffed.

But the doctor didn’t think so, and trundled the bride off for her emergency appendectomy.

They had a few quiet weeks after that, convalescing. In January they left for Washington to attend the President’s Birthday Ball, planning to go on to New York—where Ardis was committed for personal appearances—figuring they could squeeze in a few evenings of seeing the city together. The United States was at war by this time, and Bill knew that the honeymoon must be now or never—for he had decided to enlist.

Meantime Paramount moved up the starting date of his final picture to the day after the Birthday Ball. Bill flew home to work, and Ardis went on to New York alone.

On April 15th, Bill finished his picture and on April 17th he enlisted in the Army.

Among the problems which Ardis and Bill had “settled” in advance during that year of waiting was the one all career girls face with the approach of a baby.

When that happened, they agreed Ardis would retire—devote all of her energies to her two most important jobs of wife and mother.

So Brenda Marshall stepped out of films, when she was at the peak of her career and became plain Mrs. Bill Holden, a decision she says she has never regretted.

When their son was born on November 17, 1943, Bill flew home from his station in Texas and chose the baby’s name—Peter Westfield Holden, after his brother, Bob Westfield Beedle, then flying dangerous combat missions over Europe.

Bob’s gay letter welcoming his new namesake was the last word Bill ever had from him. Only a few weeks later, the Beedles were notified that their son had been killed in action.

For the final nine months of his Army service, Bill was transferred to the Motion Picture Unit’s west coast post at Culver City, where he could live with his family.

Those who knew him in the Army say that he never beefed. He knew that some actors were faking their way back into civilian life. He wouldn’t, although he was going into debt for the first time in his life, and it was eating his soul.

He stuck it out to the end, and so returned to a movie business already recovered from its former leading-man shortage. And it was eleven months before Paramount found a suitable role for his re-introduction to the public.

The months of inactivity provided a welcome rest and a chance to get acquainted with his family, which had increased early in 1946 with the arrival of a second son, Scott Porter.

Inevitably, however, soon after Bill started working again, it became apparent that there was more gunpowder where that first blast came from. The “new” Bill Holden, the explosive Bill Holden, shook the screen in “Union Station.” And in “Born Yesterday,” there it was again—dynamite under control.

Moreover, Bill didn’t use his stored-up ammunition just in front of the camera. When—after the smash success of “Born Yesterday,” Columbia proposed to cast Bill in what he called “a trite old-fashioned conception of a motion picture,” he said, “No, thanks.”

The studio was aghast. Bill Holden didn’t rebel. Bill Holden was a “nice guy.” Nice and tractable.

But, with time, with Bill quietly going on suspension rather than make that movie, the Hollywood producers learned what the Beedle family had discovered when Bill was a little boy: not to be fooled by his pleasant, casual exterior—that he’s high voltage underneath—Mr. Dynamite.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1952