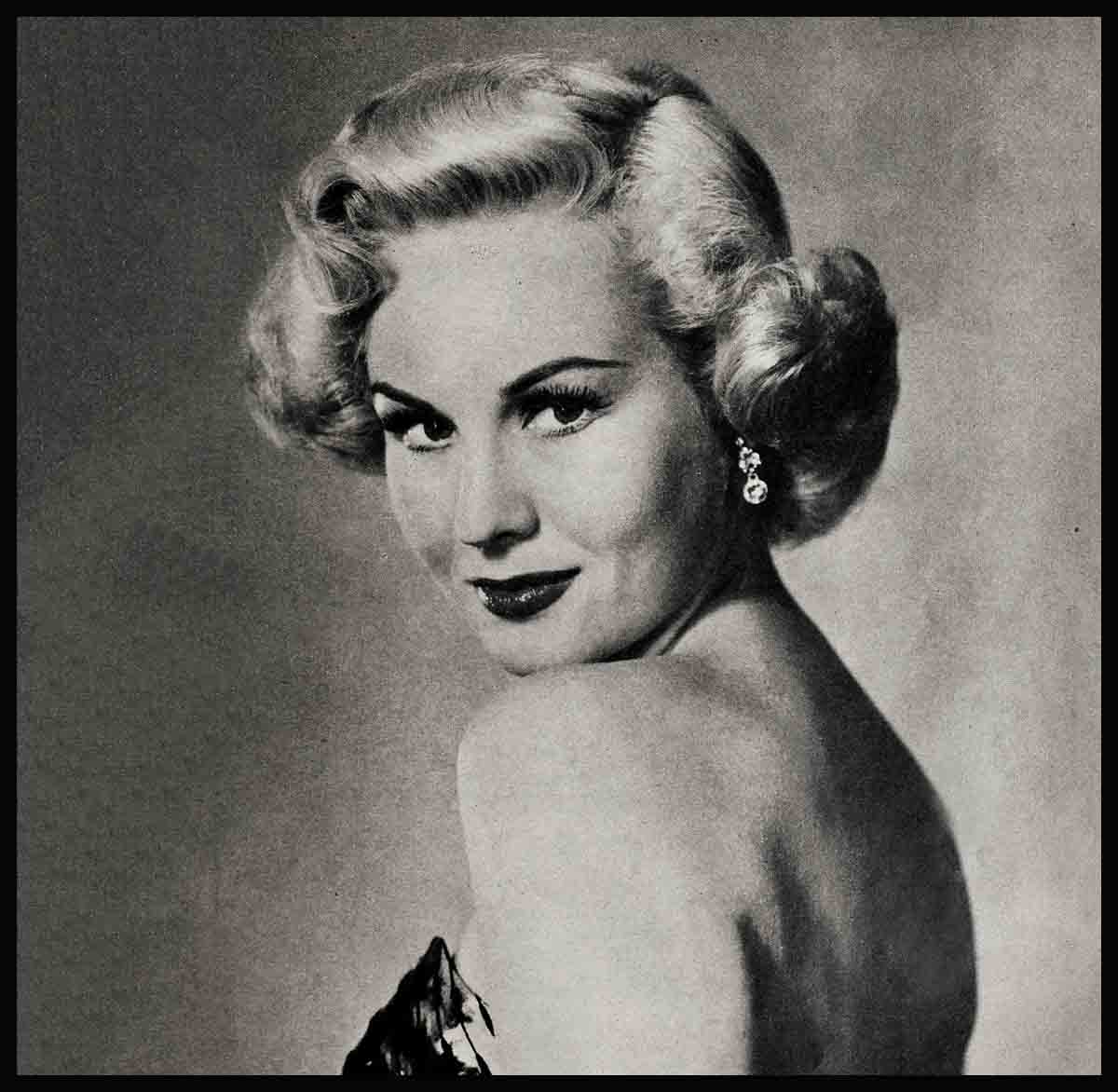

Mama Mayo—Virginia Mayo

There’s a new baby out at the O’Shea place, name of Mary Catherine. There is also a new house, or practically a new one. For a creature who weighed in at seven pounds and three ounces, Miss O’Shea has displaced more than her share of plaster, roofing, bricks, paint and wallpaper.

It all began quite sensibly, in what Virginia and Mike prefer to think of as an orderly routine. When they got married back in 1947, they agreed that they wanted children but would prefer to postpone them until such time as their careers were on an imperturbable beam. This decision is wise in Hollywood, where careers are easier to build if they are not interrupted by maternity and the consequential inactivity. Said Mike, whose own place in show business had been established with the years, “We—meaning myself and any children we might have—will make way for Virginia’s career. It has begun to go, and if anything interrupts it, her success might get sidetracked.” In tune with this decision, he turned down a handful of movies in order to stick by Virginia while she was on her way up. When she went to Europe to make Captain Horatio Hornblower, Mike planned to go with her. “But—” his agent spluttered, “but we have pictures for you.”

“You do ’em,” said Mike. “I’m going to Europe with my old lady.”

He believes that marriage thrives when the man and his wife stay together, instead of wandering around the world separately. So when Virginia had chances in Hollywood. Mike turned thumbs down on a couple of Broadway plays (one was the smash hit Goodbye, My Fancy) knowing that if they were successful he would be away from home for at least a year.

So it went, and Miss Mayo eventually was contracted by Warner Brothers and became a fixed star. Five and a half years after their wedding, Mike and Virginia said, “Now is the time.”

It happened just like that, as though they had written the order on a sales slip. To this day Mike looks in wonder at anyone who suggests that the O’Sheas were lucky to have their order filled so promptly. This was the way they had planned it, you see. Why shouldn’t it happen?

So, things were going along just right. The baby would be born in November. That gave Virginia time to finish Devil’s Canyon and Mike the opportunity to clear up some TV chores and make It Should Happen To You. Then all they had to do was sit and wait.

“We ought to get the space problem settled, though,” said Virginia.

“Space problem?” said O’Shea. “A baby doesn’t take up much space.”

“Well, with your room and my room and the housekeeper’s room, where shall we put him? Her?”

“Build a room.”

“But where? The kitchen’s on one side, and our rooms are too close to the property line to put it on that side, and if we put it on the back—”

“We’ll build up,” announced Mike. “Put on a room upstairs. The foundation should be able to take it.”

From that moment, orderliness disappeared from the atmosphere, and a cloud of confusion rolled in. True, a baby doesn’t take up much room, but as anybody knows who has remodeled a house, every stone unturned means another $500 worth of work. It began with the foundation. Mike’s optimism about the strength of the existing one turned out to be a mistake, and a good deal of shoring up had to be done. This was followed by the problem of slicing off the roof. It had to be sliced low, or the second story would sit up so high that the whole house would look like a shoe box standing on end. So it was sliced so low that Mike and Virginia spent a week of evenings sitting in their livingroom and looking up at the stars. They lived in the diningroom, kitchen and bedrooms, skirting the hole in the middle, and thanking Providence that it doesn’t rain in the California summer.

The chimney had to be raised nine feet, so they decided they might as well have the whole thing rebuilt-with new brick. The new roof made the old roof look like a stray cat, so the entire thing was recovered. The entrance, in order to match the new facade of the house, was graced by a new porch, and Mike decided they might as well have new screens and new sashes all over the house. The addition had to be painted, spanking new, of course, so they repainted the whole house white.

They agreed that the room and bath upstairs wouldn’t be the best place for a baby, that. a baby should be downstairs. Mike relinquished his old room downstairs for the nursery and planned the new one upstairs for himself. Virginia’s bedroom, redecorated in yellow and shades of brown, adjoins the nursery. This leaves Mike free to continue his night owl habits, reading into the wee hours, while Virginia hits the hay at her customary early hour.

Midway through this Operation Upset, it occurred to them that insulation might be advisable. It would keep the neighborhood noises from the baby’s ears and the baby’s noises from the neighborhood ear. In addition to new roof, new ceiling, new foundation and new paint, they found themselves with new walls. And; naturally, new paint and new wallpaper.

It was a bumpy, busy months of construction, and before it was over Virginia announced that it was time for her appointment at St. John’s Hospital. That was on the morning of November 12. On hearing the news Mike made a motion as if to leap for the garage and the car.

“Sit down,” said Virginia. “Eat your breakfast.”

Mike insists he was not nervous, that in any situation of impending danger he grows gimlet-eyed, his nerves become steel, that the adrenalin surges through his system, making him icy calm. He cannot, however, claim that he was as nonchalant as Mrs. O’Shea. Fatso, as he lovingly called her in those days, ate a substantial breakfast and sat around a while before she deigned to begin the trip. On the way they made occasional stops, at Virginia’s request, to ogle the furniture in Wilshire store windows. She wanted a lamp for a table in the front window, and the lush. lamp displays could not be ignored. Mike put his foot down when Virginia showed a willingness to tour an open house.

“Oi-veh!” he said, taking his hands from the steering wheel and holding the sides of his head.

“Couldn’t we go in?” suggested Virginia. “There’s plenty of time.”

“No,” said Mr. O’Shea, who was silently calling on his system for a fresh supply of adrenalin.

At the hospital they found a substantial group of reporters who had been notified by Virginia’s studio that the event was about to take place. The collective press was one jump ahead of a fit. Virginia swirled calmly past, with Mike trailing.

Mike spent almost every minute with his wife before she went into the delivery room. He used the remaining few minutes to case the joint. There were signs here and there which read, “No Admittance,” but no one seemed to care, so Mr. O’Shea passed blithely by them and under them. The long row of labor rooms leading to the delivery room sheltered several women in the same boat with Virginia. In spite of their condition, some of these patients took time out to notice that Mike O’Shea was scooting around the corridor. Mike is a gregarious guy, and summoned by some of these damsels in distress, he trotted happily into their respective rooms and chatted briefly with them. As Mike says, “A maternity ward in a hospital is like a jail or the Army—everybody there is everybody else’s friend.” Nevertheless, he was shaking his head at the fact that he’d been asked for his autograph. Of all places!

Virginia was wheeled into the delivery room shortly before seven o’clock that evening. The doctor, leaving Mike, shook hands and said cheerily, “Well, this is it.”

“Don’t be nervous,” grinned Mike, “whatever you do. Everything’s going to to be all right.”

It was, Mike says, the greatest performance of his life.

At the doctor’s suggestion, he went back to Virginia’s room to wait. It may have been an eternity to Mike, but by Greenwich mean time, it really wasn’t long before a nurse came in and told him his daughter had been born. Mike went down the hall to the waiting room where the press gang was sitting, minus fingernails. He wore a smug expression and rocked on his heels several minutes, building suspense. Finally somebody giggled nervously, “What’s new, Mike?”

“It’s a girl,” he announced, and when the reporters, half of whom were women, buckled into a mass of sentiment, Mike fled.

He scurried down the hall toward the nursery, and posted himself where he couldn’t be seen. By this time he knew the layout and he was sure that the next baby to be admitted to the nursery would be Mary Catherine O’Shea. It was a name chosen by Virginia and Mike as a salute to the grand old names. When they had discussed the problem they had concurred on the fact that people nowadays tend toward embroidery. Names like Snap, Clutch and Katch seem to be fashionable tor boys, and girls are being snowed under with tags like Dawn, Sundown and April. The O’Sheas wanted something simple, a name that was a name and not a cereal slogan. “Mary Catherine” seemed to fill the bill. Where did the choice come from? “From nowhere,” said Mike, “except from a couple of pretty good saints.” Besides, they figured that eventually their child will be called Kate O’Shea, a monicker that tickles Mike because it is the name of the only illustrious ancestor he could dig up—the colleen who was the sweetheart of Charles Parnell, Irish Nationalist leader of years gone by.

Standing near the door, he didn’t have long to wait before a nurse wheeled a newborn infant toward him. Mike stepped into her path. “Whose little demon is that?” he inquired.

The nurse stiffened. “This is no demon. This is a beautiful little girl—the O’Shea baby.”

Pop O’Shea grinned. “She’s mine. Let me have a little look at her.” He noted with pleasure that the baby had red hair. This would please Virginia. All these months she had said that, boy or girl, she hoped the baby would be a redhead. Once the nurse had taken the baby inside the warm nursery, she unwrapped her and held up a naked Kate O’Shea for her father’s inspection through a big window. Across the baby’s derriére was a strip of cloth labeled, “Girl O’Shea”. Mike smiled. “Okay,” he said. “We’ll keep her.”

He went back to Virginia’s room to wait for her, and when she was brought through the door he kissed her and she said, “Mike—she’s a redhead.” Mike told Virginia he had already seen their daughter and that her first performance had been a striptease.

He wandered around a bit after that, visiting various new acquaintances who had become mothers since his first meeting with them in the labor rooms. Being Mike O’Shea, he sat on the beds and shook hands and asked about their babies—and the husbands sat there and beamed. He went back and told Virginia about it—“What a place, a hospital!” When she laughed at him he suggested that if any strange men came into her room, she should throw them out.

The next morning. Mike mixed cement for the patio with the air of a man not quite in this world, and for the next few days kept himself so busy with mortar, brick and flagstone between hospital visits that he managed to talk himself out of noticing the emptiness of the house. Mrs. Young, the baby’s nurse, arrived before Homecoming Day, and he bragged a bit to her about having a daughter. “Girls are wonderful,” he said. “Boys—well, men want sons as sops to their own egos. Give me a girl any day.”

He didn’t give Virginia a gift. The O’Sheas are not gift-giving people, at least on holidays or occasions. They pick up assorted surprises for each other on odd days of the year, and dislike any custom that makes people obligated to buy presents. When a baby shower was suggested for Virginia, Mike had said, “No, please—she wouldn’t like that.” Nor did he give cigars after Mary Catherine’s arrival, or send out announcements. “That’s a corny bit,” he said. “It’s like saying ‘Look at me—Look at us.’ It’s nothing special to anybody but us.” And so, when asked if he gave Virginia a gift, he smiled and said, “I gave her the baby.” That is Mike’s way of saying that if a man gives his wife love and devotion all through his life, it is the best gift he can give.

One day, several weeks after Virginia and Mary Catherine were settled in the “new” house, Mother O’Shea had a thought.

“You want more, don’t you, Mike? More children, I mean?”

“Sure,” said O’Shea.

“There will be a space problem.”

“Oi-veh!” said Mike.

“What would we do?”

“This one,” said Mike, “this one room cost us as much as a complete five-room house. Next time we’ll build same, and make it all bedrooms to accommodate the influx.”

“Yes, dear,” said Virginia.

THE END

—BY SUSAN TRENT

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954