Lovely Young Lady Diana

PART II

In her mid-teens, Lady Diana Spencer, youngest of the three daughters of Edward John “Johnnie” Spencer, Viscount Althorp and 8th Earl Spencer, and Frances Ruth Burke Roche, was enrolled, as older sisters Sarah and Jane had been before her, at West Heath, a boarding school for girls in Sevenoaks in the county of Kent.

West Heath was of a breed of institution that still, as late as the 1970s, was more concerned with educating young girls of the upper classes in the social graces—preparing them for suitable marriages—than in turning out scholars. This was well understood by the Spencers and it was fine with Diana. She was in no way a memorable student, even by West Heath’s amiable standards; she would fail her O-levels twice while enrolled. In fact, though pretty, tall and friendly enough, she didn’t stand out much at all. The overall impression among classmates and teachers was of a girl who was fun but already possessed of that somewhat drifty aspect the world would come to know so well.

There was, however, one thing about Diana that was indeed special then and would remain so to the tragic end of her too-few days. It is the main reason why, on the 20th anniversary of her death, we choose to pay attention once again, and remember her lovingly.

Twice weekly, West Heath girls would be bused to Darenth Park, a large old hospital in Dartford serving the mentally and physically handicapped. The trips were made in the spirit of volunteerism, but truth be told, many of the students dreaded them. In Rosalind Coward’s biography Diana: The Portrait, Sarah Spencer, Diana’s oldest sister (six years her senior), recalled the unpleasantness: “I remember them opening enormous wooden doors like in a medieval castle—you know, the ones you’d have to take a battering ram to. It smelt of disinfectant and pee . . . you saw this sea of ill people just coming toward you . . . [T]hey were all people with mental problems, serious mental problems. We had never seen places like this. We were sheltered little girlies.”

The hospital manager, Muriel Stevens, knew of the girls’ disquiet. “It was intimidating to walk into that huge place with the level of noise and to see some of the very severely handicapped people,” she said in Tim Clayton and Phil Craig’s book Diana: Story of a Princess. “Some of them would be in wheelchairs. Some of them would be sitting on chairs and needed encouragement to move to get off them.” Others needed no such encouragement, and for the girls this was scarier still: [T]hey were just so delighted to see these young people they would rush up and of course they would touch their hair, grab their hands. And if you’re actually not used to it that can be very frightening.”

Into this situation walked Diana, and she was instantly in her element. “Diana was never frightened,” said Stevens. “She was extremely relaxed in that setting, which for a young person of her age was incredible.”

Stevens continued her reminiscence: “That tremendous laugh! That joyous sound! And it was wonderful because you wouldn’t actually know what she was laughing at, or have any idea at all what had amused her, but at the sound alone you would find yourself smiling, and as you got closer and you heard it more, you’d find yourself laughing.”

Other times, you might cry. The girls were asked to move the wheelchair patients about in a little dance as music played. Many of the West Heath students did so haltingly if not grudgingly, of course holding the chair from behind. Diana would stand in front of the chair, grab hold and dance backwards, smiling at her partner, who would be transported.

Empathy.

The writer and editor Tina Brown was talking to the English journalist and historian Paul Johnson, who had known the late princess, about this quality for her book The Diana Chronicles. Johnson, famously a Roman Catholic who often writes with a moralist’s stance, said, “She thought she knew nothing and was very stupid. She made it impossible to criticize her, because she’d say ‘I am thick and uneducated,’ and I’d say, ‘I don’t think you’re thick at all,’ because although she didn’t know much, she had something that very few people possess. She had extraordinary intuition and could see people who were nice, and warm to them and sympathize with them . . . Very few people compare to what she had.”

Empathy.

It was empathy, compassion and a very rare and unquestionably genuine common touch— “I’m much closer to the people at the bottom than the people at the top,” she told the French newspaper Le Monde in the last interview she gave before she died—that made her, as Tony Blair declared, “the People’s Princess.”

How she came by this special ability to not only make a connection but inspire true affection is very hard to say.

The Honourable Diana Frances Spencer was born on July 1,1961, at home in Park House, Sandringham, Norfolk. We understand such an address conveys little to an American audience, but those in the know in England would immediately ask, “Sandringham? Sandringham?” And the answer would be, “Yes, Sandringham.” Park House was not on the quaint main street of the coastal Norfolk village but on the edges of the famous 20,000-acre estate—the thing that gives “Sandringham” a name—an estate that was (and is) owned by the British royal family. Johnnie Spencer and his family lived there at the time of Diana’s birth. The Spencers, as it happened and as might be assumed considering this circumstance of proximity, went way, way back with the royal family. It is lovely to note that, today, Park House is the Park House Hotel, still on the royal grounds but no longer a private residence, rather dedicated to housing the disabled and their caregivers. Diana would love that.

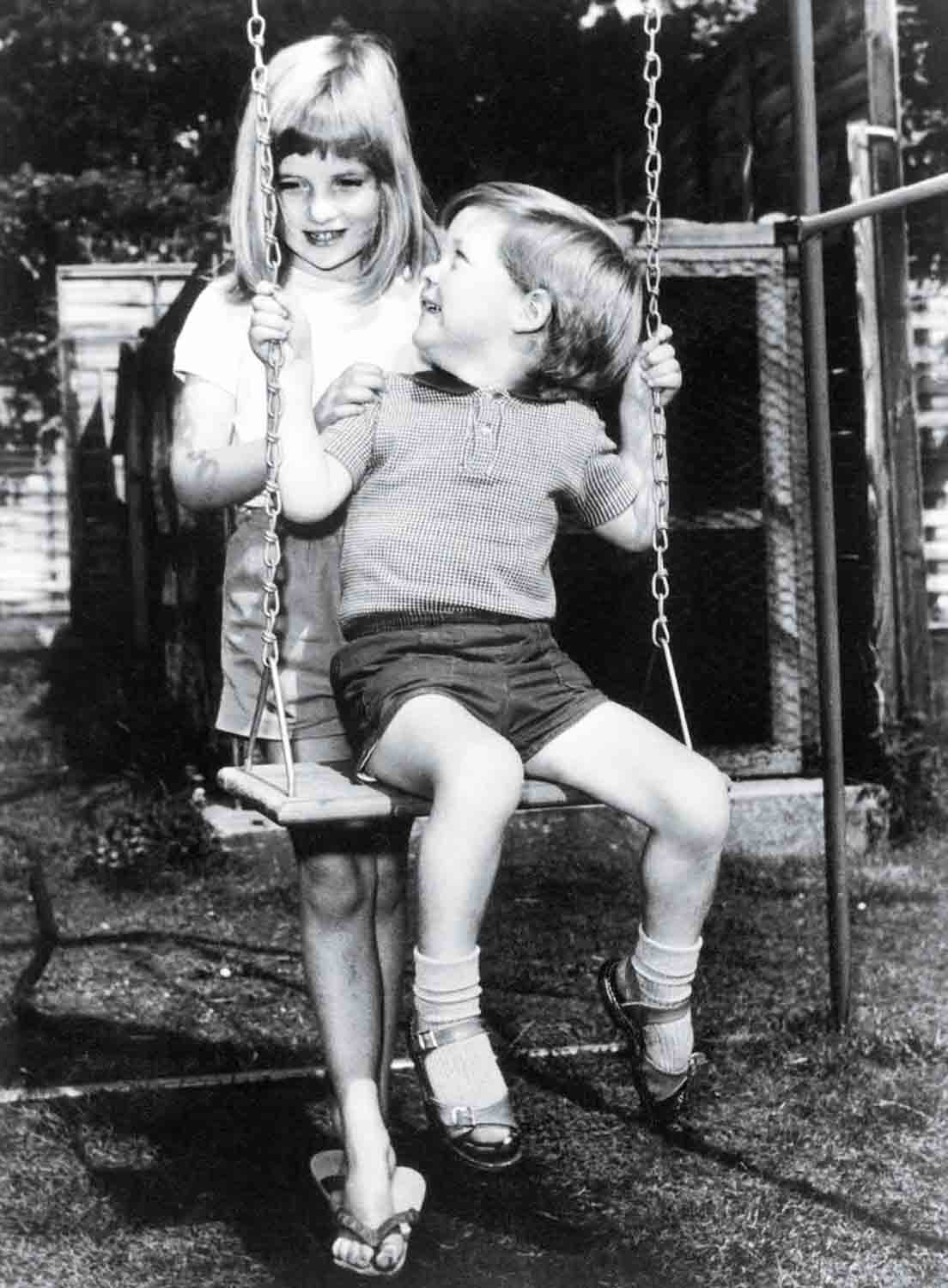

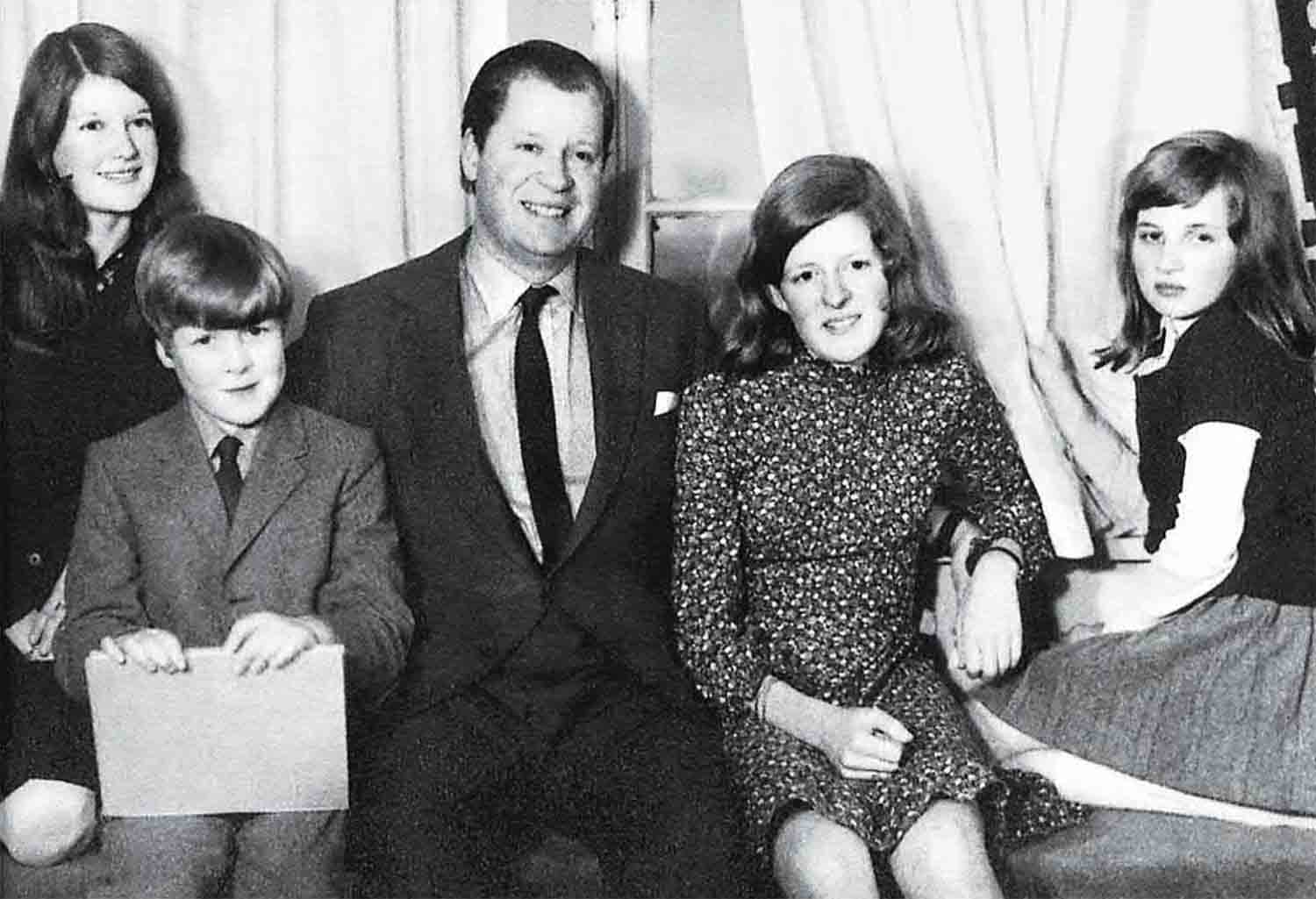

But in 1961, Johnnie and his wife, Frances, were raising their family there, and adding to it with their third daughter. They already had Sarah and Jane, and there is no doubt that the advent of Diana was a disappointment to her father at least: He was anxious for a male heir to whom he could hand down his title and possessions, a boy who would eventually become Earl Spencer, holder of the imposing Northamptonshire estate Althorp. Johnnie’s dismay was never manifested toward Diana, whom he loved, but resentments were growing between him and his wife, who had earlier given birth to a boy who, tragically, did not live—plus the two girls. Frances would eventually deliver Charles, who is today 9th Earl Spencer. He was the young man who movingly (and provocatively, even defiantly) eulogized his sister Diana in Westminster Abbey in 1997.

So Diana’s upbringing was top-loaded and frightfully fraught before she was old enough to know it. She was a babe in arms and her parents already had issues with each other. Her two older sisters, still girls, were being groomed to be eligible female catches for men of title, and her father was pushing for a boy. She grew up distraught. Who wouldn’t?

Johnnie Spencer liked to pull out his camera—perhaps he envied Lord Snowdon, the photographer married to Princess Margaret—and Diana was happy to pose. As said, she loved her father, and she loved her mother as well. And they loved her. But this was no becalmed Baby Boomer nuclear family. This was an upper-crust unit with certain members who aspired to even greater nobility than the Spencer name already conjured in the 1960s and ’70s.

To put it quickly, simply and dirtily (in a way that we Americans can understand), the prestige came from the paternal side—the Spencers—and the money came from the maternal side—the Fermoys. Johnnie’s ancestors had always been cozy with the throne: The first Duke of Marlborough was an ancestor, and in fact the Spencer children, Sarah, Jane, Diana and Charles, were related to King Charles II (reign: 1660-1685) on their father’s side through four illegitimate sons. They were also kin to Charles’s successor, James II (1685-1688), through an illegitimate daughter. Members of Diana’s mother’s family, a predominantly Scottish and Irish clan whose considerable fortune was in large part the bequeathal of an American relation, the heiress Frances Work, had been employed by King George VI (that King’s Speech fellow), his wife, Elizabeth (best known as the cherry-cheeked “Queen Mum”), and his daughter (a.k.a. Queen Elizabeth II, the still presiding monarch). The Spencer girls, breeding and beauty taken into account, would be expected to marry high. The 2011 wedding of Diana’s son William to Kate Middleton shows how much English mores have changed in only a generation: These two intelligent young achievers met at one of the world’s great universities, fell in love and chose to wed. That’s a typical smart-young-people story, with the added fact that Kate was what is known as “a commoner”—i.e., one not from the British aristocracy. When Sarah, Jane and Diana Spencer were in their adolescence and young womanhood in the 1970s and ’80s, the rules were vastly different, and royals and otherwise grandly titled men were looking to wed societal peers. The Prince of Wales, who is traditionally first in line of succession to the throne and who happened to be Charles in this time frame, was required to seek a partner who was estimable, lovely and virginal. Believe it or not: This was not three thousand years ago, it was less than 50.

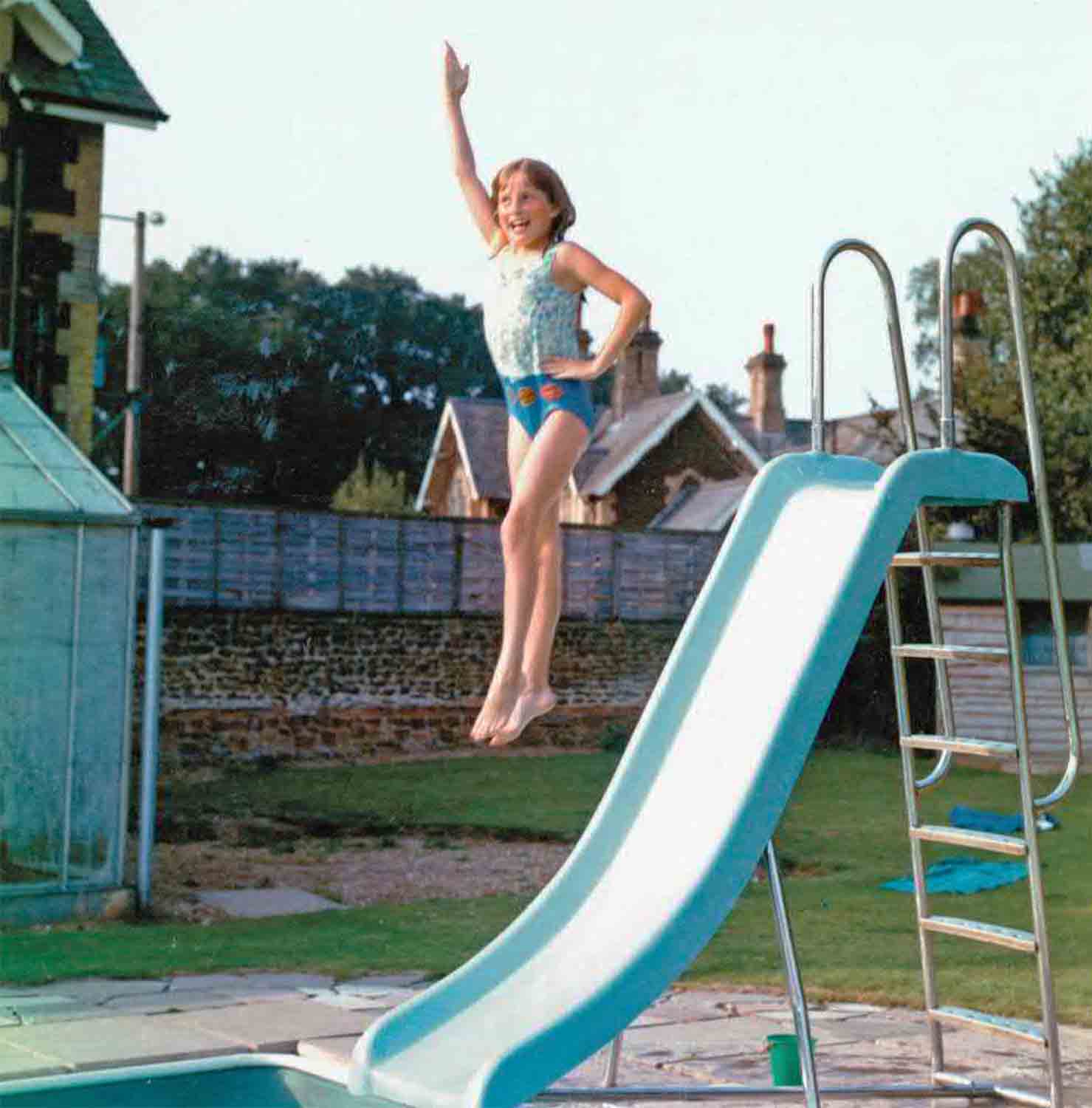

As it happened, Diana was preparing herself, and not always unwittingly, to be that woman. She was accomplished at swimming and piano, and she once won a school prize for being kindest to her pet, a guinea pig. She socialized with boys but was reticent in love. She devoured Barbara Cartland romance novels and imagined her own Prince Charming (“The only books she ever read were mine and they weren’t awfully good for her,” said Cartland herself in 1993). Diana fell in love with Charles from afar, and wondered if one day he might be hers—in much the same way girls once fell in love with Paul McCartney or do today with Harry Styles (but, in fact, with a far more realistic shot at such an outcome). In 1975, she officially became, at age 14, a titled Lady when her paternal grandfather died and her father inherited his earldom. “I’m a Lady,” Diana declared as she rushed down a corridor at West Heath. “I’m ‘Lady Diana now!”

If she was jubilant in that moment, she wasn’t a happy girl. Her parents had divorced when she was eight, and she had been brutalized by the family split. The story at the time—and it remains the standard version—was that Diana’s mother had entered into an adulterous relationship with the also-married Peter Shand Kydd (whom she would eventually marry), and that therefore Johnnie Spencer was awarded custody of the kids. On paper, that is true, but affairs at the time were far more complicated. Prances Spencer did not desert the family, as her children were led to believe, but desperately wanted to be with her daughters and son. During the acutely acrimonious divorce proceedings, crucial testimony was given by Frances’s own mother—Diana’s maternal grandmother—that Frances was an unfit parent. Several biographers have alleged that this older woman, Baroness Fermoy, so lusted after status that she had once prodded her daughter to marry Johnnie Spencer, and now publicly denigrated that same daughter so that her heirs might remain “Spencers.” The entrenched beastliness of the British aristocracy endures in the modern age.

In any event, the Spencer kids saw their mother as a bolter, and were at least mildly surprised when, at the end of a weekend visit with her and her new husband on the island of Seil on Scotland’s west coast, Frances cried. In 1976, their father began his own affair with a married woman, Raine, Countess of Dartmouth (who was Barbara Cartland’s daughter). Johnnie married her after she obtained a divorce, and Diana and her siblings disliked this match just as much as they did their mother’s to Peter Shand Kydd. Diana manifested her anger by being mean to her nannies, none of whom stuck with the family.

The Spencer girls, 1977: Sarah was gregarious, socially ambitious and a target of many men; Jane was smart and also out on her own; and Diana, just turning sweet 16, was more than ready to leave school behind. She would not join her father and detested stepmother at musty Althorp in Northamptonshire. She would, instead, with a head full of dreams, go to London.

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE AUGUST 2017

No Comments