The Wedding Of The Century

PART IV

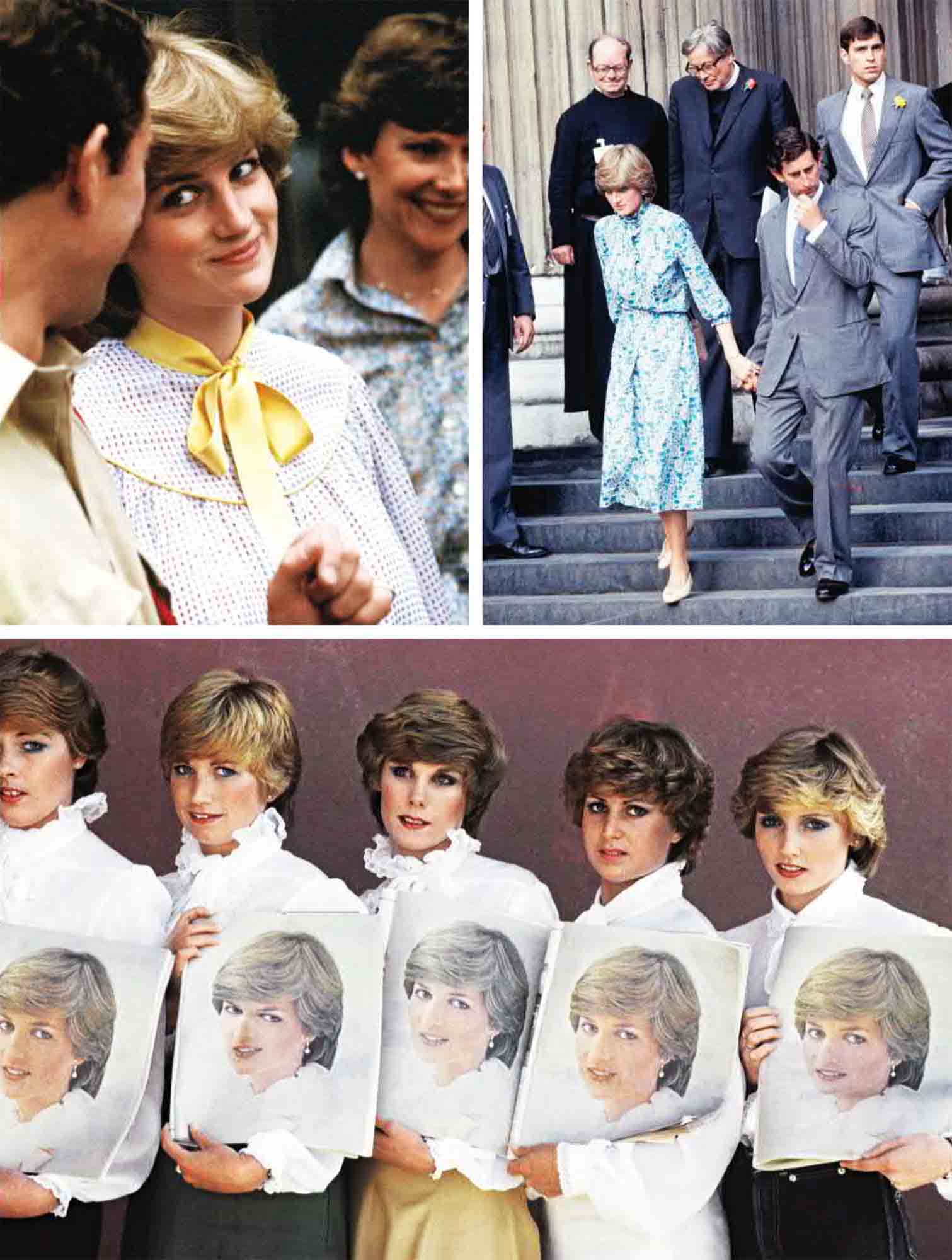

Diana Spencer, as we have seen in her childhood pictures, was a cute, chubby-cheeked little girl. Lady Diana was a teenager who was teased by her siblings and friends for her occasional gluttony.

Indeed, when the mood was upon her, she could and would pack away the foodstuffs. Still, she was always growing upwards more than outwards, and her increasing loveliness, which evolved into true, world-class beauty, eventually became apparent to all. Her sister Sarah once remarked that, within the family, there was no talk through the years that Diana was en route to becoming any kind of goddess, while admitting that she sometimes heard comments from friends that this was happening. By the time Diana was linked to Prince Charles, most observers felt that he had chosen the most beautiful lass in the land.

But Diana’s self-image regularly didn’t match what was seen by her burgeoning horde of fans, “her public.” Concerning “Shy Di,” as the papers called her: She hadn’t ever really been shy, though her lowered head and hunched shoulders tended to imply shyness in the paparazzi photos, but she was beset by insecurities. Stronger, older and more experienced women than Diana would have been affected by the pressure of an approaching role in the Wedding of the Century. Diana was not laid low by this pressure, but unquestionably she suffered under it.

She was only 19 when it all started, and barely 20 by the time it was finished. Charles was a dozen years her senior, a cocksure man of the world who was approaching his nuptials from an entirely different perspective than was his fiancee. He had been in an absolute torment about proposing marriage, writing to a friend in January of 1981: “I do very much want to do the right thing for this country and for my family. But I am terrified sometimes of making a promise and then perhaps living to regret it.” After having put Diana through a hellish holiday season of silence, he finally pulled the trigger, and Diana celebrated her engagement girlishly. She returned to her flat in Coleherne Court and said to her friends, “Guess what?”

“He asked you. What did you say?”

“Yes, please.”

They shouted and jumped like the Beatles had done in that Paris hotel room when they’d learned “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had gone to Number One in the States; then the girlfriends went out driving around in circles in London to burn off their excitement.

There was the briefest interim of relative calm between the February fact of betrothal and the public announcement, and then the maelstrom truly swept in, engulfing Diana. Even as just a candidate, she had been pursued by the Fleet Streeters, and had sometimes been found by friends in tears inside the doorway of her apartment building. Yes, true, conceded: Diana had, from the get-go, a preternatural gift for manipulating the media and having them adore her, as Tina Brown and others have emphasized, but at some point the pursuit was so egregious and savage, no person—certainly no 19-year-old—should have been forced to endure it. Diana was forced to do so, and if Charles cared, he cared not much.

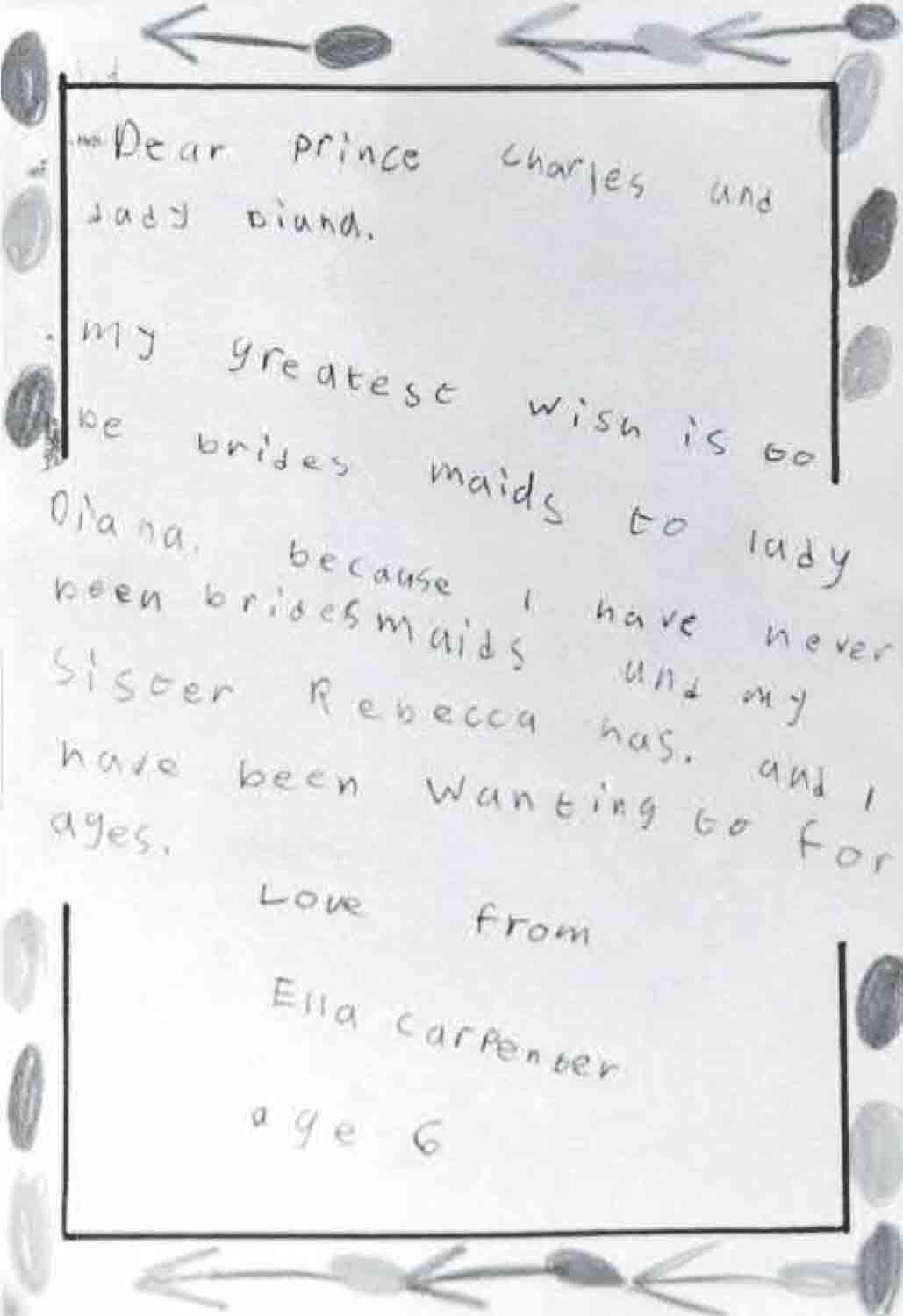

He did little in the period between the engagement and marriage to boost Diana’s confidence, to shore her up for what was coming. As we learned in the previous chapter, he was ready to lay into her for questionable clothing choices, and at one point after withdrawing his hand from her waist he wondered at how “chubby” she seemed to be. When Diana looked at newspaper pictures of herself in her blue engagement suit, which she and her mother had bought at Harrods and which had elicited more than a mite of derision in the press, she saw herself as overweight. A season of tension-fueled bulimia ensued. As the rest of the whole wide world eagerly prepared for the glorious wedding—block parties were scheduled through Great Britain, invitations to midnight galas were sent out in Australia, the morning TV shows in America shipped convoys of personnel and materiel to London—Diana wasted away. “This little thing got so thin,” her friend and former flatmate Carolyn Pride told Andrew Morton. “I was so worried about her.”

The designers Elizabeth and David Emanuel had fashioned the scandalous black dress that Charles had so detested, but they retained Diana’s favor; Elizabeth was put in charge of the wedding gown, even though many at the Palace raised an eyebrow over the choice (as they did when Charles and Diana selected St. Paul’s Cathedral over traditional Westminster Abbey as the site of their wedding). Between the first fitting and the last, Elizabeth saw her client’s waist shrivel from 29 inches to 23½. “Great anticipation. Happiness because the crowds buoyed you up,” Diana told Morton about the lead-up to the ceremony, while adding quickly: “I don’t think I was happy. We got married on Wednesday and on the Monday we had gone to St. Paul’s for our last rehearsal and that’s when the camera lights were on full and a sense of what the day was going to be. And I sobbed my eyes out. Absolutely collapsed and it was collapsing because of all sorts of things. The Camilla thing rearing its head the whole way through our engagement and I was desperately trying to be mature about the situation but I didn’t have the foundations to do it and I couldn’t talk to anyone about it . . . I had a very bad fit of bulimia the night before . . . I was sick as a parrot that night. It was such an indication of what was going on.”

The sun comes up (or very often doesn’t, not in any bright kind of way) very early in a London summer. On July 29, 1981, dawn washed over the city just after the witching hour, and the young and hardy who had camped out in the streets in order to secure good viewing places rubbed their eyes, as Diana did hers at five a.m. at Clarence House. The most dedicated of her public would be joined in London on this day by many thousands of her countrymen—600,000 celebrating outside St. Paul’s Cathedral, 3,500 inside. For some, the work was done and the day represented, if not an anticlimax, a chance to savor triumph.

Lepidopterist Robert Goodden, whose company, Lullingstone, had prodded worms to spin the silk for Elizabeth s gown in 1947, had done the same, admirably, for Diana’s Emanuel creation. Royal baker David Avery, in conjunction with Belgian pastry wizard S.G. Sender (“cakemaker to the kings”) and others, was wiping the flour off his apron after helping create 27 wedding cakes, and was planning to “play golf, and lose myself for a week.” Chorister Geoffrey Taylor and his 37 mates from St. Paul’s had done all the rehearsing they could with a music program personally selected by Prince Charles—hymns like “Christ Is Made the Sure Foundation” and “I Vow to Thee My Country”—as had the Royal Opera Orchestra, the English Chamber Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra and the New Zealand superstar soprano Kiri Te Kanawa. They were now primed and hoping for the best. In the event, they would all, of course, perform wonderfully.

Alarm clocks went off in New York City, dessert was served in Los Angeles, corks were popped in Sydney, TVs were switched on globally—perhaps a billion people would attend this event, one way or another—and Diana was dressed. “I was very, very calm, deathly calm,” Diana told Morton about that morning. “I felt I was a lamb to the slaughter. I knew it and couldn’t do anything about it.”

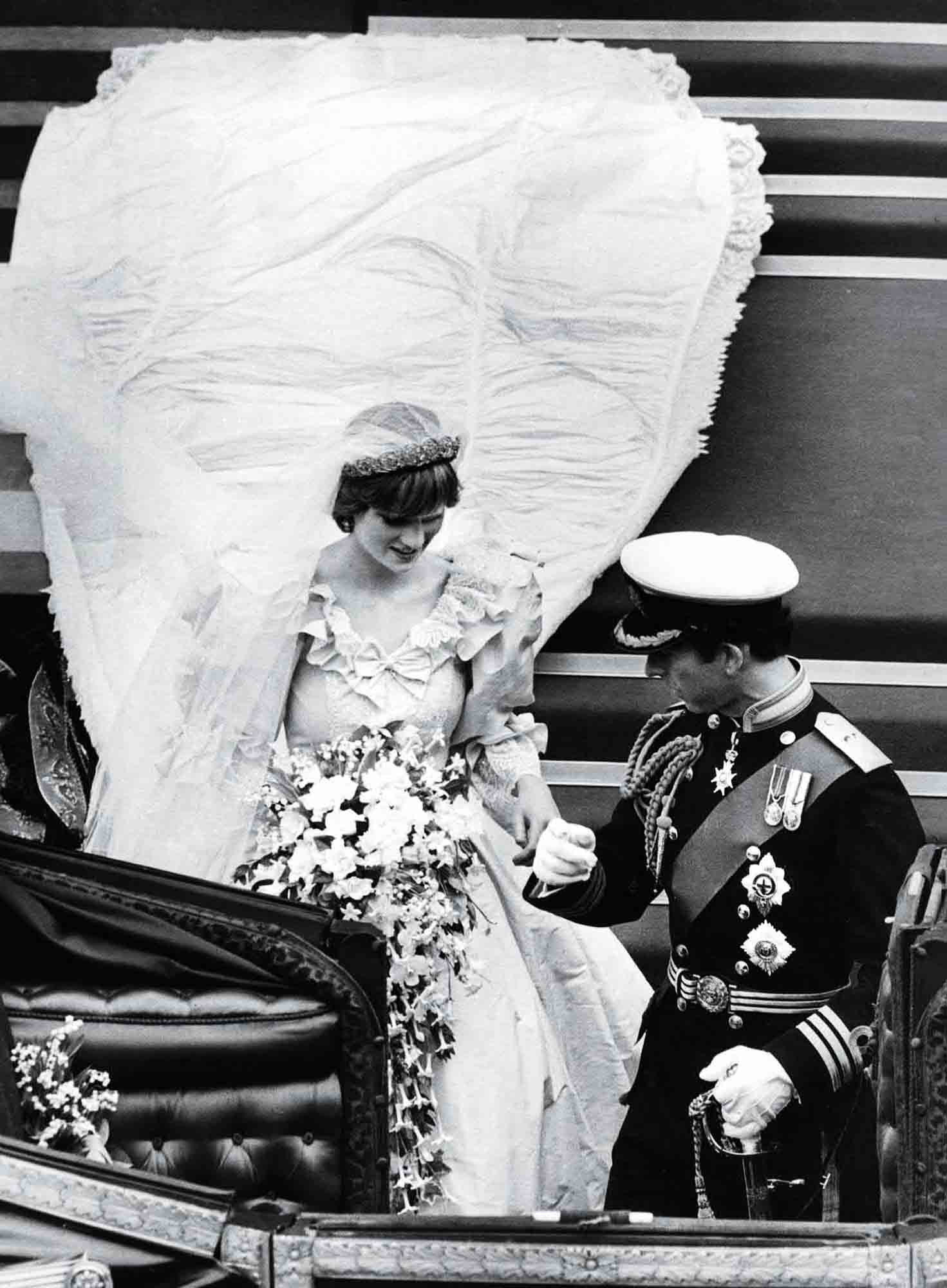

It is well-known among dedicated royals watchers that in 2011 Kate Middleton purposely chose to arrive at Westminster by car for her marriage to Charles and Diana’s son William: that Kate wanted to distance herself from comparisons to Diana and, more important, from the hoariness and grandiosity of certain royal traditions. In 1981, the thinking was quite the opposite. St. Paul’s had been chosen over Westminster in part because it was larger, could fit more hundreds of people, and would necessitate a longer, slower, more huzzah-filled parade route to get there. Diana would make that trip not in any kind of crass gas-powered conveyance but in the Cinderella-esqne Glass Coach, pulled by two bays, including the legendarily purposeful mare Lady Penelope, who could “take any procession in stride,” as attested by royal coachman Richard Boland. This was not merely pomp and circumstance writ large. This was pomp and circumstance in IMAX 3-D surround sound, volume jacked to the max with a cherry on top—and lots of whipped cream.

When Diana emerged from the coach, the crowd oohed and aahed at her hitherto-top-secret silk taffeta gown with billowing sleeves, bows, lace flounces, sequins, pearls and a 25-foot train that kept spilling out of the coach for what seemed like minutes, as the clapping and cheering continued. The veil was of ivory silk tulle and glittered with 10,000 (you read that right) inlaid mother-of-pearl sequins, the whole of it held in place by the Spencer family’s diamond tiara. If this is precisely what Diana had dreamed of back when she was a little girl with a headful of impossible wishes, well, this is precisely what she got. With the additions, of course, of a less-than-commit- ted husband-to-be and his mistress-in-waiting on the guest list.

To be sure, Diana was on the lookout for her: “Walking down the aisle I spotted Camilla, pale grey, veiled pillbox hat, saw it all, her son, Tom, standing on a chair. To this day you know—vivid memory.” That this should be a bride’s personal takeaway from a wedding so many others enjoyed so rapturously is terribly sad, even tragic. But there it is, and was.

It is unfair to say that Diana was alone on the day of her marriage—certainly her father, though physically enfeebled, brought her forth, and her friends and other relations were in the cathedral—but a quick review of her team of bridesmaids and flower girls, many chosen and all of them rubber-stamped by Charles and the Palace, is illustrative of what she was getting into. The lead girl and therefore de facto maid of honor, 17-year-old Sarah Armstrong-Jones, Charles’s cousin and Princess Margaret’s daughter, was in the procession, and Charles’s goddaughter India Hicks, and a daughter of one of Charles’s close friends, and his racehorse trainer’s daughter . . .

They all were lovely, done up by Emanuel so that they looked, as The Times of London put it, as if “they could have been plucked from a Victorian child’s scrapbook.” But they had come via Buckingham, not Althorp. When Diana’s eldest son, Wills, married Kate, Kate’s sister, Pippa, was, officially, close by her side.

Famously, both bride and groom showed jitters during the ceremony, stumbling just a bit. During her vows before the Archbishop of Canterbury, Diana called her betrothed Philip Charles Arthur George instead of Charles Philip Arthur George, and Charles said “with all thy goods I share with thee” instead of “all my worldly goods I share with thee.” No matter (and, in fact, quite charming), the ceremony was officially concluded, the music (yes, Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance”) swelled, the bells rang out and it was off to the Palace in the State Landau.

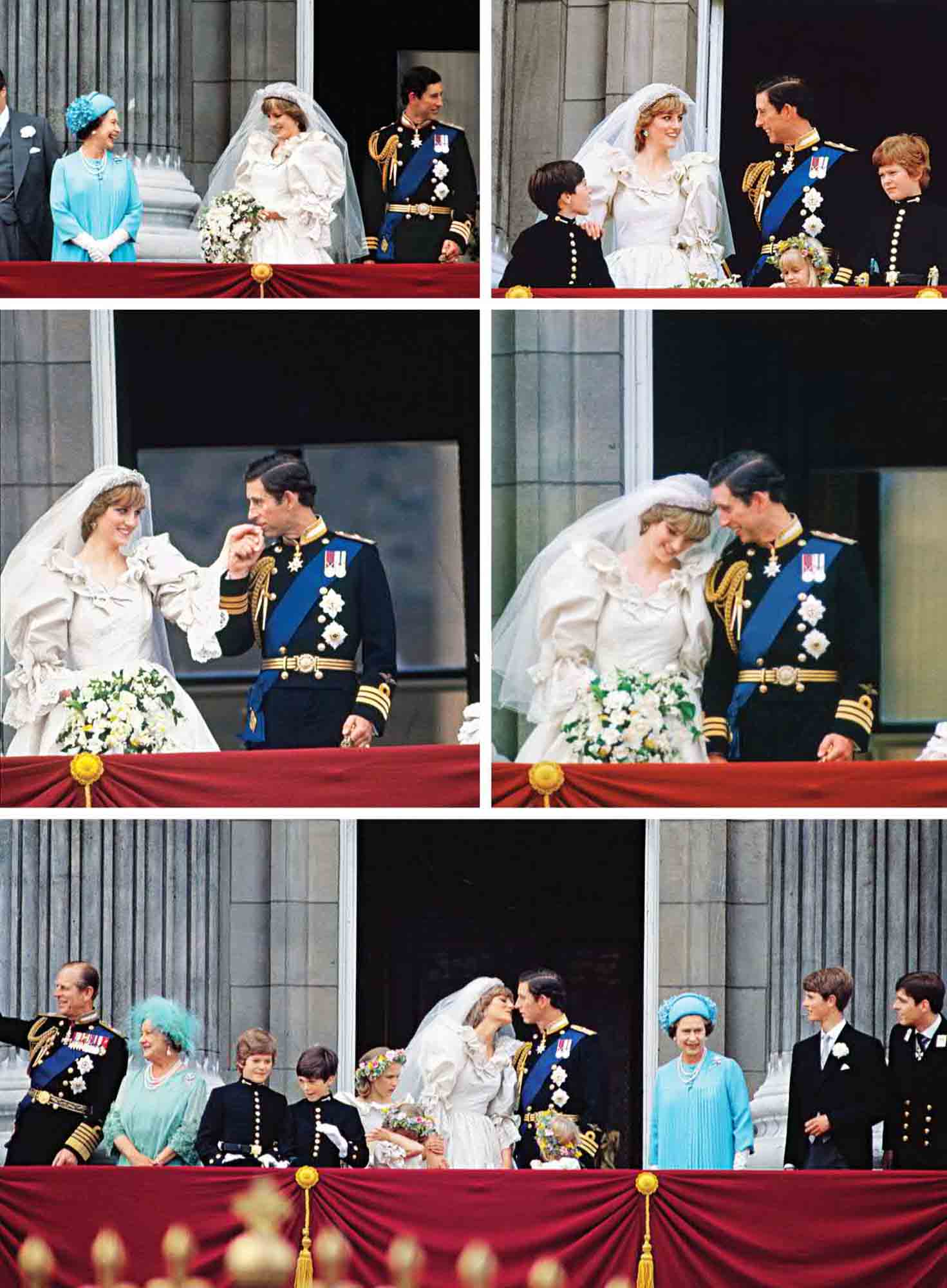

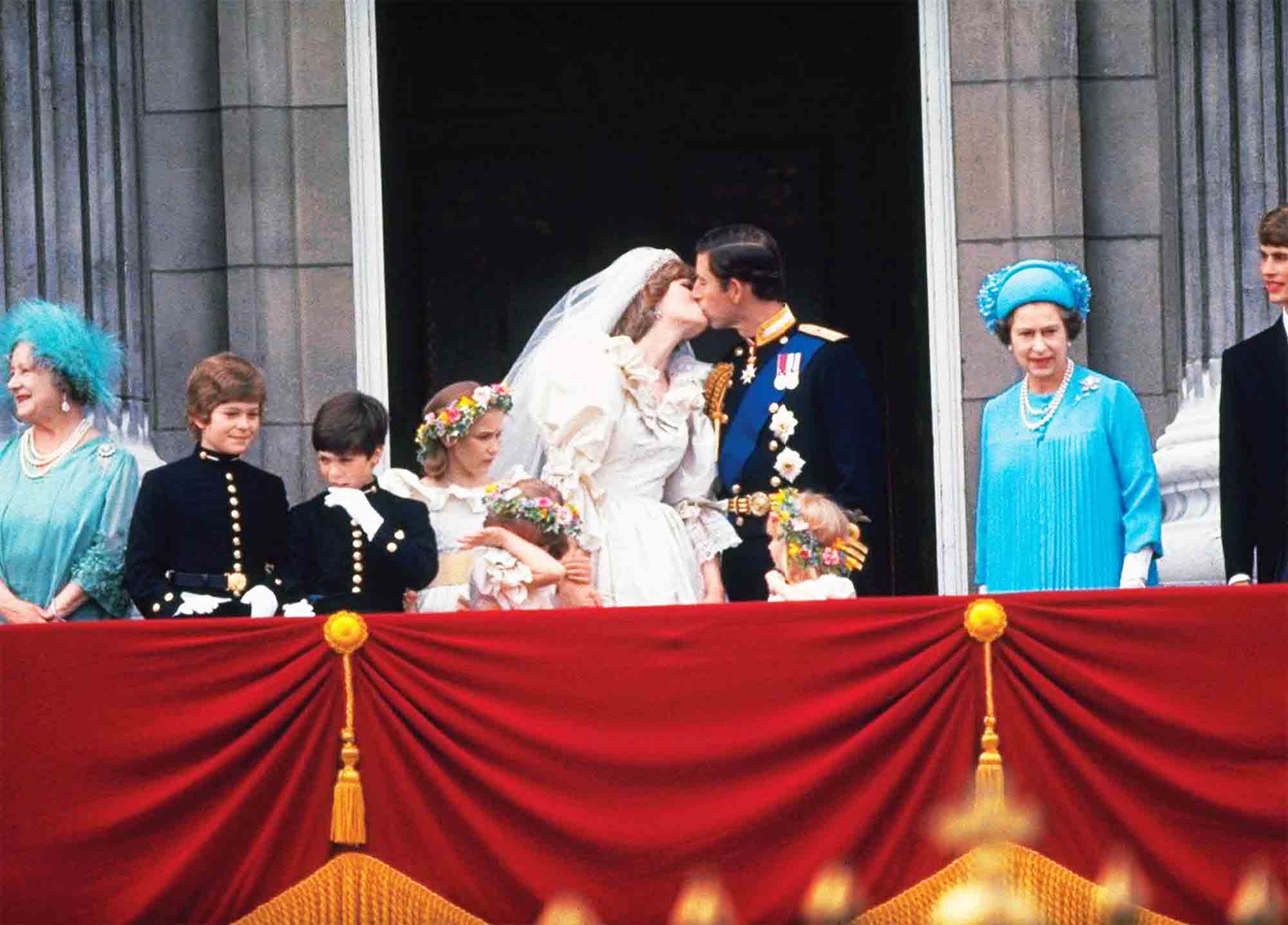

There, they appeared on the balcony at about one o’clock British Standard Time, before ducking back inside to host a wedding feast for 120. The crowds pressing in at the gate

shouted their only demand.

“I am not going to do that caper,” Charles said to Diana. “They are trying to get us to kiss.”

“Well, how about it?” asked Diana in return.

The prince paused and replied, “Why ever not?” He embraced his wife warmly, and even greater cheers rang out.

This was far better for Diana than the engagement announcement had been. Only five months earlier, an ITN TV interviewer, expecting an obvious answer, had asked the newly betrothed, “Are you in love?”

“Of course,” Diana had answered with a laugh.

Charles had offered: “Whatever ‘in love’ means.”

ITN and other media buried the remark at the time, wanting to preserve the fairy tale that was unfolding before Britain’s eyes to the delight of all. But Diana had heard her fiance distinctly, and though she never asked him to explain further, she would always remember.

After much toasting at the Palace, Charles and Diana made their way to the landau, now decorated with a JUST MARRIED sign that had been attached by Charles’s brothers, Andrew and Edward, and were driven over Westminster Bridge to Waterloo Station, where they would board a train for Hampshire and the beginning of their honeymoon. The Wedding of the Century was ended, but never to be forgotten. In 2011, even as everyone everywhere was buzzing about William and Kate, a stale, bite-size piece of Charles and Di’s wedding cake that had descended from a sergeant in the Royal New Zealand Air Force sold at auction for $290. Many bidders had been drawn, as if to the original flame, by the romance of it all.

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE AUGUST 2017

No Comments