The People’s Princess

PART V

She was, in that instant in 1981, the world’s best- known personage and arguably its most beloved (two distinctions she would successfully hold for the remainder of her days). Before she ever cradled a sick infant at a children’s hospital or comforted an AIDS sufferer at a hospice or showed herself as an exemplary mother to her boys, she was already the Peoples Princess (as British Prime Minister Tony Blair would formally dub Diana in the aftermath of her death).

Her grand and generously shared marriage ceremony had been a smashing success, her demeanor had been charming and mysteriously alluring, and now Diana’s public knew no global boundaries.

And she was also, in that instant, thoroughly, entirely, grievously alone.

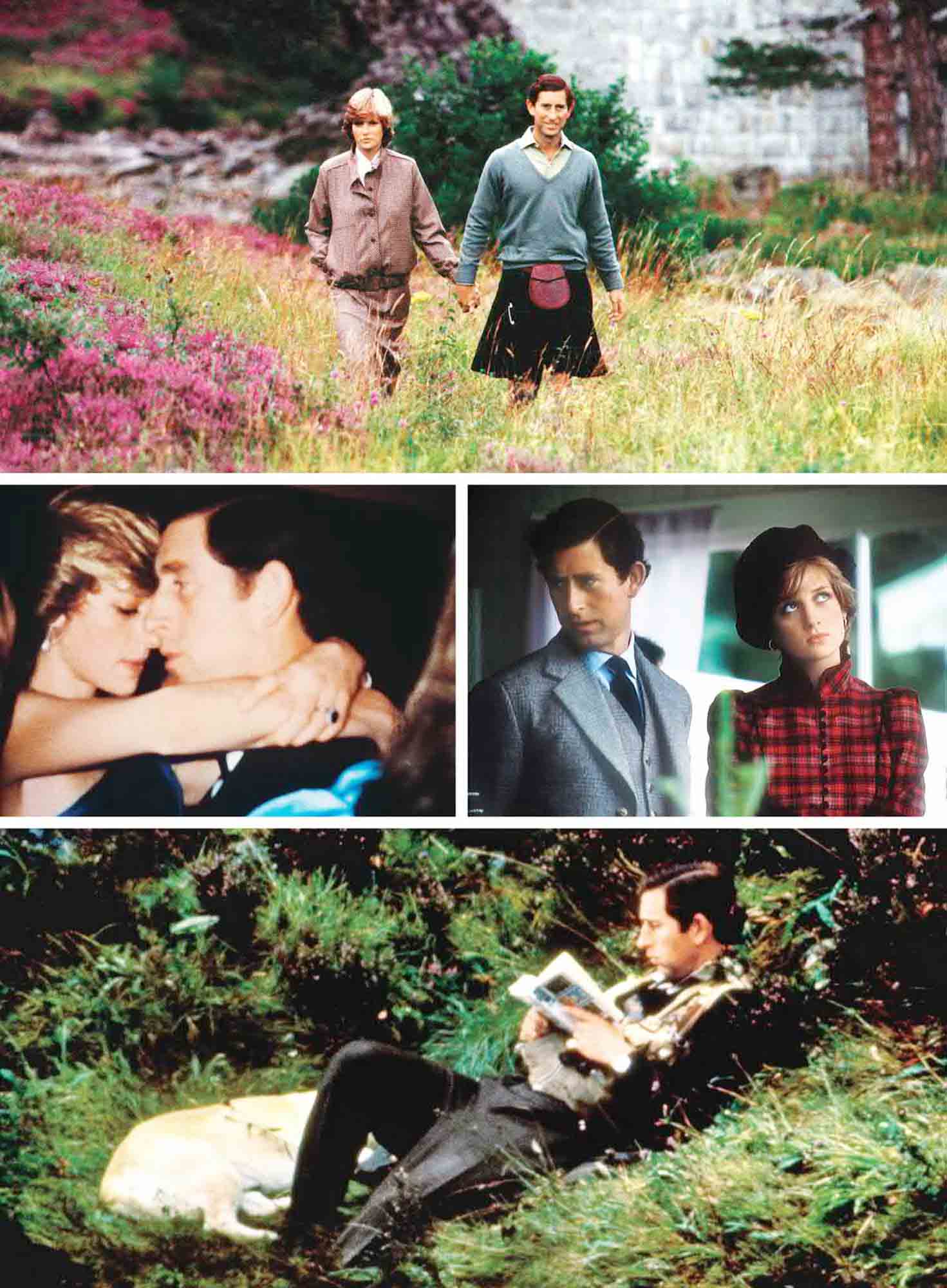

Her biographers take different tacks in their narratives and they take different sides, with the widest routes probably charted by Andrew Morton’s constantly victimized Diana and Tina Brown’s often crafty Diana. But on this they agree: The Charles-and-Di honeymoon was anything but. When did Diana know that it had all been a terrible mistake? When did she know it was already over, no matter what lay ahead? Most probably, by the second day. The second day of a marriage that would last for 15 years.

After the exhausting succession of Glass Coaches, St. Paul’s and Buckingham Palace, the train from Waterloo Station took them to Broadlands in Hampshire, the estate of members of Charles’s father’s family. There, the multichaptered, three-month honeymoon would commence (and the relationship would be consummated, in the very bed once used by Elizabeth and Philip, although many assumed at the time and assume today that connubial relations had already occurred between Charles and Diana).

Diana told Morton of her first hours as Princess of Wales: “I never tried to call it off in the sense of really doing that but the worst moment was when we got to Broadlands. I thought, you know, it was just grim. I just had tremendous hope in me, which was slashed by day two. Went to Broadlands. Second night, out came the van der Post novels he hadn’t read [Laurens van der Post, the South African philosopher and adventurer, was much admired by Prince Charles]. Seven of them—they came on our honeymoon. He read them and we had to analyze them over lunch every day.”

How does the old song go? Isn’t it romantic?

We do want to stress here that we are seeking a balanced account, which is a thing almost impossible to achieve when recounting the saga of Charles and Diana, two ill-matched people whose relationship has, in its aftermath, been commented upon by each partner’s passionate partisans, usually with a goal of slamming the other partner as culprit. When it comes to their affairs and missteps, we will try to be fair in these pages. In the case of the crummy honeymoon, however, it seems there’s no doubt. The above passage concerning Charles’s coldness is attributable to Diana via Morton. But here’s Tina Brown, who is often skeptical of Morton’s Diana- friendly biography, writing in her own The Diana Chronicles: “To Andrew Morton she itemized all the particular acts of rejection by Prince Charles that were the cause of her desolation—the photos of Camilla that fell out of his diary as they cruised the Mediterranean on Britannia, his retreat into his solitary, highbrow reading, the cuff links from Camilla he wore in defiance of his new wife’s feelings—but the really terrifying dimension to her grief was the sudden sharp understanding that all the things that had oppressed her during her engagement were now her life forever. It was like an icy wave hitting her in the face. The oldness the coldness, the deadness of royal life, its muffled misogyny, its whispering silence, its stifling social round confronting sycophantic strangers, this is how it would be until she died. Nothing else can explain the violence of her panic. As a former member of Prince Charles’s staff put it: ‘She saw she was going to become like the queen, possibly the loneliest person in the world’. . . When I think of the young, beautiful, newly married Princess of Wales at this time, I see her sitting up abruptly in the middle of the night in the Spartan spaciousness of her bedroom at Balmoral and uttering a long, bloodcurdling scream . . .”

To parse a few of the phrases above:

—The cruise on the royal yacht Britannia was Phase Two of the lengthy honeymoon, after Broadlands. “We had to entertain the boardroom on Britannia,” Diana told Morton, “which were all the top people every night so there was never any time on our own. Found that very difficult to accept.” As Brown reported in her book, 21 naval officers, a crew of 256 men, a valet, a dresser, a private secretary and an equerry were “sharing their romantic getaway” on the yacht. Yes, that might be very difficult to accept, and as Brown wrote further, with fine humor: “The trouble was that in this shipwreck movie there was no stowaway Leonardo DiCaprio to ravish Diana under the tarpaulin of a lifeboat. Instead, there was the Prince of Wales trawling his way through the complete works of Laurens van der Post.”

— As for “the violence of her panic”: On board ship, “the bulimia was appalling, absolutely appalling,” admitted Diana. “It was rife, four times a day on the yacht . . . I remember crying my eyes out on our honeymoon. I was so tired, for all the wrong reasons totally.”

— Regarding: “She was going to become like the queen.” No, she wasn’t, as we shall see. No way, no how.

— And finally: the despair in “her bedroom at Balmoral.” Phase Three of the honeymoon, beginning right after the Britannia had docked, was carried out as part of the royal family’s cherished late-summer getaway at the queen’s Scottish castle, and so now Diana’s audience of midshipmen was exchanged for the far more austere and less friendly Windsors, including the queen; her husband; the Queen Mum; Charles’s siblings, Anne, Andrew and Edward; Princess Margaret (Elizabeth’s sister and Charles’s aunt) and Margaret’s two children; and on and on. At one point Diana asked Charles if, please, she could return to London. He said no. He told her to buck up. She did not, and it was noticed. One evening the queen commented to a dinner guest, according to Tim Clayton and Phil Craig in Diana: Story of a Princess, “Look at her sitting at that table glowering at us!”

In all past centuries, the royal family would have won: Diana would have been handed her head, figuratively or literally. But here was the rub for Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip and all the others of Buckingham Palace: They and Charles had constructed this marriage on the ancient ways of doing things—the only ways they knew. These ways presumed, in any royal union, evasions, suppressions and rueful acquiescence. But the royal family had found themselves— seemingly to their surprise if not astonishment—at the end of the 20th century, in a time where love affairs might well be conducted but might also have consequences; where marriages were entered into but sometimes led to divorces; and women might become complacent with their role or might find their own path.

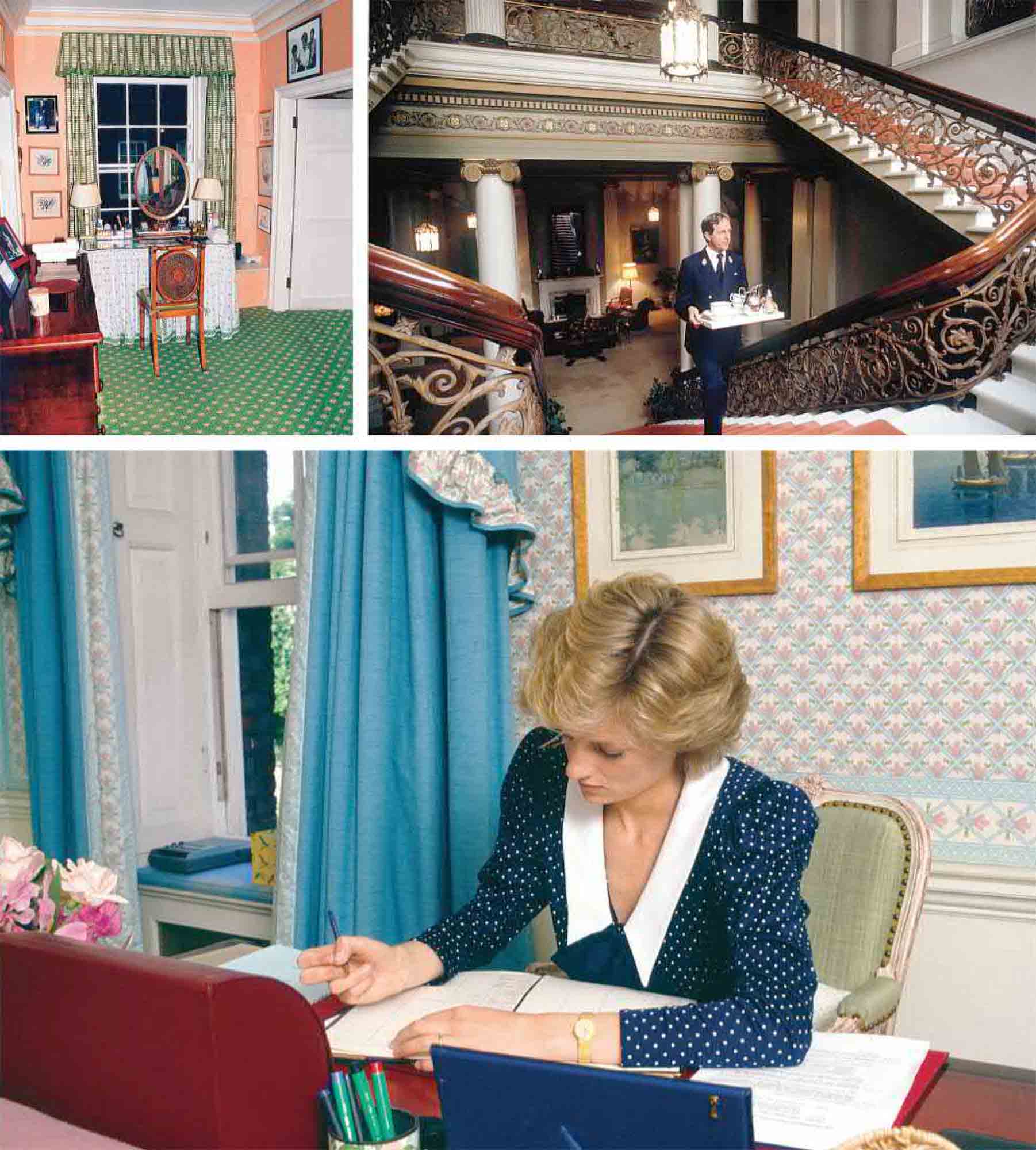

The honeymoon ended after a lot of cruise control aboard the Britannia and then at Balmoral in October of 1981, and finally— finally!—Diana proceeded back to the city, to a new and fancier address at Kensington Palace (after a few months in Charles’s Buckingham Palace apartment while the new digs were readied), where she would find not only her path, but her estimable, intrinsic—instinctual—and altogether marvelous talents.

Diana was so quickly and publicly pregnant after the wedding that even the cover story in People magazine, not the cheekiest or most aggressively provocative of the world’s many scoop-seeking weeklies, couldn’t resist a little fun: “It seemed as though the rice had hardly been swept off the steps of St. Paul’s before Britain was proudly atwitter over a new royal announcement: The newlywed Diana, Princess of Wales, is expecting to deliver an heir to the throne sometime in June. After a brief pause during which ‘the nation’s mums counted on their fingers,’ as one wry observer put it, the Buckingham Palace switchboard was jammed with congratulatory calls, hundreds of well-wishers gathered at the gates, and Fleet Street hailed the WONDERFUL NEWS in banner headlines.

“The blessed event, if all goes well, will occur a prompt if perfectly proper 11 months after the July 29 wedding.”

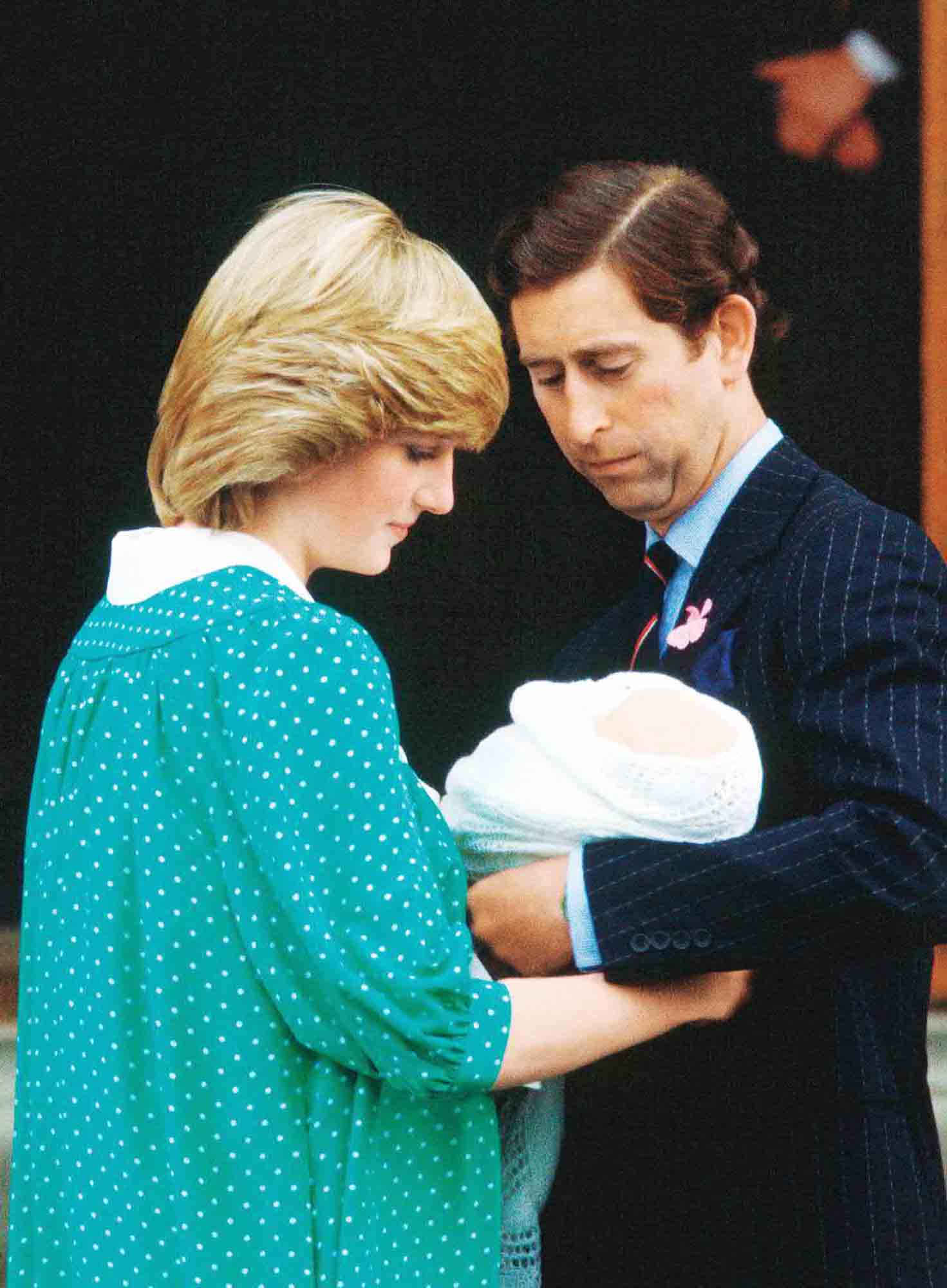

So at one point during the horrid honeymoon, between the princess’s bouts of bulimia and the prince’s sulky sessions with his mystical novels, something must have gone momentarily right, and the end result would mean all the difference to Diana. Motherhood was something the young Princess of Wales needed in this desolate period, something she could do, and, as it eventuated, something she could do very, very well.

She didn’t have the easiest time getting there, as morning sickness was a constant. She was often fatigued, especially when she went out and about fulfilling her new, princessly duties. Oddly, her travail only served to boost her runaway popularity. When a photograph ran of Diana nodding off during a function at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—a photo that was captioned the next day in newspapers worldwide “The Sleeping Princess”—the universal reaction was: “Ohhh, the poor dear!” Anyone who didn’t love Diana was cold-as-ice, heartless, soulless.

Her first official, extended tour outside the city was a trip to Wales with her husband, where she wowed the crowds, meanwhile thoroughly (and completely unwittingly) dwarfing the man by her side, who was, after all, “the Prince of Wales.” This was a harsh wake-up call not only for Charles but for the Palace: They had allowed someone into their stoical midst who, with her natural warmth and charm, would outshine them all in the hearts and minds of the masses—who would be revered in a way that they never had been and never could be. Diana, the young teen who had bonded with the mentally ill patients and was, only yesterday, a modestly employed nanny and kindergarten teacher, put her practiced talents and innate empathy to use as she greeted a Welsh child suffering from spina bifida with a hug. She bent her knees, and looked into all the youngsters’ eyes on their level. Although in highbrow royal arenas this simplicity might be considered a detriment, she spoke the children’s language, she knew how to talk to them one-on-one in a mutually enjoyable manner. None of the Windsors had ever done these things or, frankly, had wanted to do them, or had even had the capacity or training to do them. Charles would later say that Diana taught him how to approach children in public.

If Diana, upon her return to London, was looking for a “well done!” from the queen or her prince—and there is no testimony that she was expecting anything of the kind—it certainly wasn’t forthcoming. Dr. James Colthurst, who as a teenager had met a younger Diana on a ski trip and had become a close friend, told Tina Brown that the result of the Welsh sojourn was that she “really got it in the neck from Charles.” In their book Behind Palace Doors, Nigel Dempster and Peter Evans quote Stephen Barry, Prince Charles’s valet, who had little use for Diana, as saying, “The princess had everything going for her except the ability to not upstage the prince.” During a visit to Althorp in this period, there was a vigorous argument between the newlyweds in which a chair and window were broken—Charles was known to throw things when in a temper—and at one point Diana tripped and fell down a flight of stairs. Diana much later claimed to Morton that this was a suicide attempt, but at the time she had reported it as a stumble, and most biographers subscribe to the contemporaneous version. Would she actually have jeopardized her unborn child? That simply cannot be imagined of Diana, and as with other incidents in the Morton/Diana account, as well as Charles’s post-divorce ripostes, there is revisionist history at play.

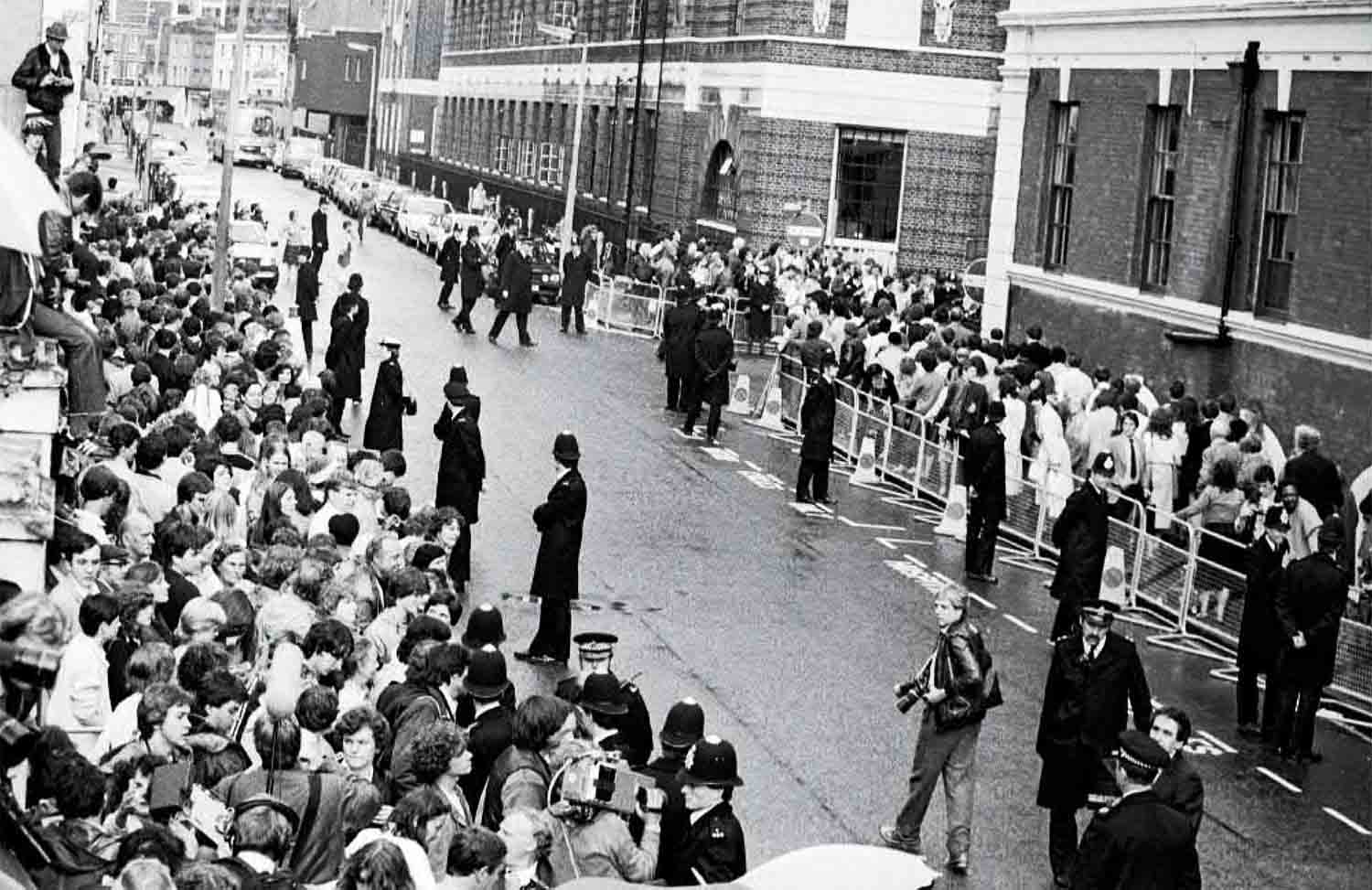

But enough, for now, of the painfully well- documented difficulties between the Waleses. Diana was about to give birth, and this buoyed her almost as much as it did her countrymen. The punters placed bets on the salient question, and everyone waited with bated breath to know: Would it be a boy? Many cultures consider that an important point, but few care about the answer more than the Brits when the royal family’s line of succession is about to be altered.

The blessed event occurred on June 21,1982, in the private Lindo Wing of St. Mary’s Hospital in the Paddington district, and word spread beyond the institution’s walls, as People magazine reported: “The 41-gun salute at the Tower of London and Hyde Park signaled a king for the 21st century. The huzzahs rose across Britain, and eyes misted over from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Well-wishers pressed to the gates of Buckingham Palace to read the placard that royal assistants hung out for the world to see last Monday eve: ‘Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales was safely delivered of a son at 9:03 p.m. today. Her Royal Highness and her child are both doing well.’

“The 7-pound 1½-ounce prince is expected someday to rule the United Kingdom. He has already commandeered the attention of his future subjects from such concerns as the Falklands and Wimbledon. Even the newborn’s father, normally the most serious of men, was transported. Charles, said his father-in-law, was ‘absolutely over the moon.’ ”

Johnnie, Earl Spencer, also said: “The baby is lucky to have Diana as a mother. I’m off to have a beer.” He was right about both Charles and the child—and where he was headed.

His Royal Highness Prince William Arthur Philip Louis of Wales (who, as we all know, later wed his own princess Kate in the most riveting royal wedding since his parents’) was christened in the Music Room of Buckingham Palace six weeks later, with Dr. Robert Runcie, the Archbishop of Canterbury—who barely more than a year earlier had presided over Charles’s and Diana’s wedding vows—pouring the baptismal water on Wills’s sensitive head and eliciting from the infant three small squeaks. Charles wiped dribbles from his son’s chin, while any medievalists in the audience were cheered that the baby’s cries indicated the Devil had been driven from the boy’s body. Elizabeth II joked of William’s vocalizations: “He’s a good speech- maker.” Charles’s self-deprecating jape at the appearance of his first son was: “He has the good fortune not to look like me.”

Charles would not reprise the line two years later when son Henry, known from the first as Harry, was born on September 15,1984, also at St. Mary’s.

“It’s a boy!” a TV crewman announced on the latter occasion to the crowd of 300 reporters, cameramen and dedicated royals watchers who had been waiting outside throughout Diana’s nine hours of labor for the birth of her second son. A cheer went up, and a rubbernecking motorist lost control of his car and crashed into an ambulance.

Diana had, in three short years of marriage, done her royal duty, providing “an heir and a spare”; her boys were now second and third in line of succession behind Charles himself.

“Three short years of marriage” that had at times seemed terribly long and borderline unendurable. The fissures in Diana and Charles’s relationship, which had been there from the first but had only grown worse, were now being insinuated by an increasingly prying press, and the extramarital affairs had been either reinitiated or begun in earnest. The consequences of these infidelities certainly would include the ultimate dissolution of the union, but what else? To this day, there is speculation that Harry, with his ginger hair, is Captain James Hewitt’s son, not Charles’s. The royals have bothered to say that DNA tests prove otherwise, and Hewitt, who has been routinely ungallant in reminiscing about his relationship with Diana—even unto cashing in—has said, in this case, that the when-when mathematics of their liaison and the birth don’t work. But the DNA tests haven’t been produced for independent examination, the mathematics are in dispute and the nattering classes carry on.

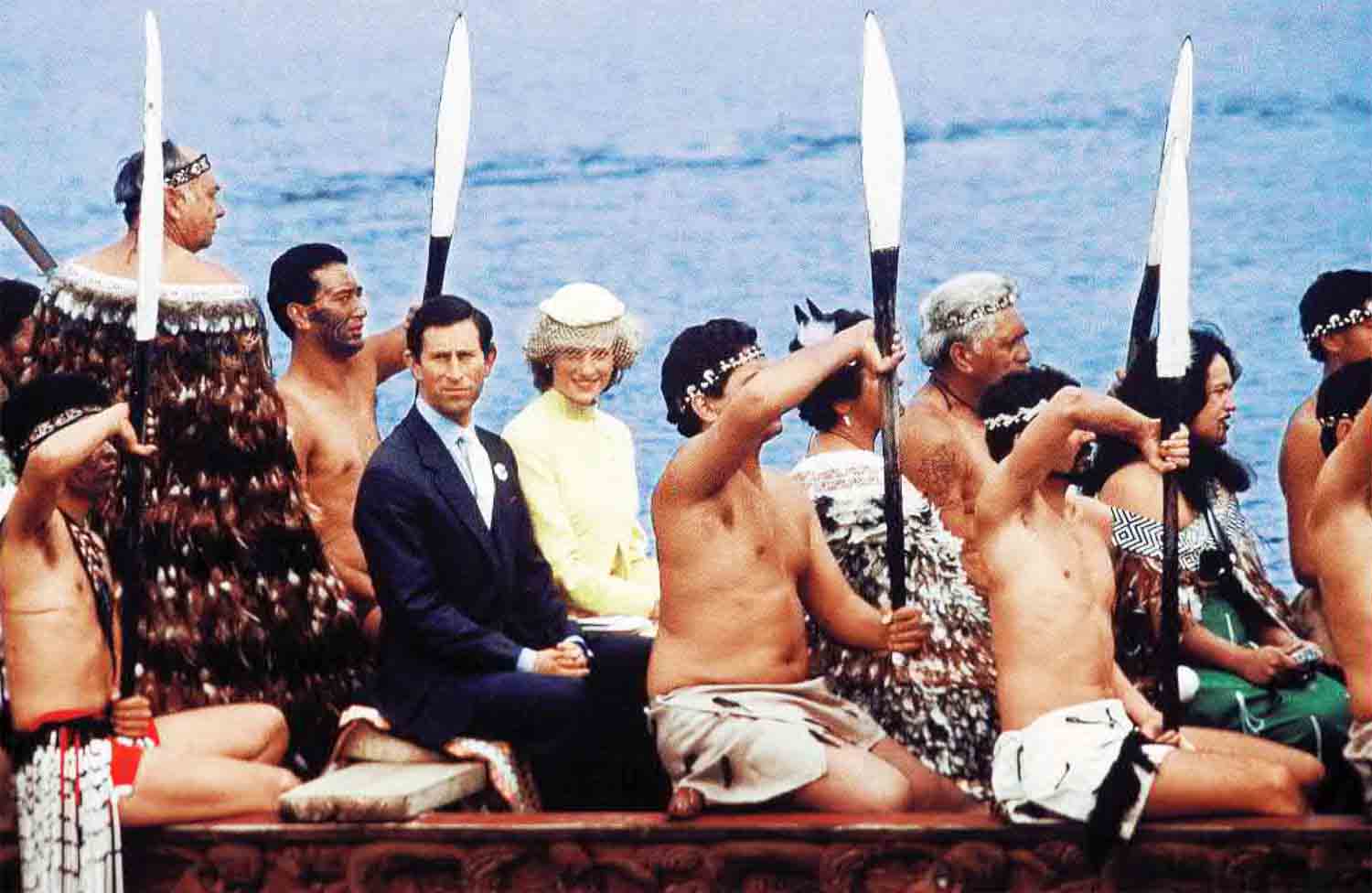

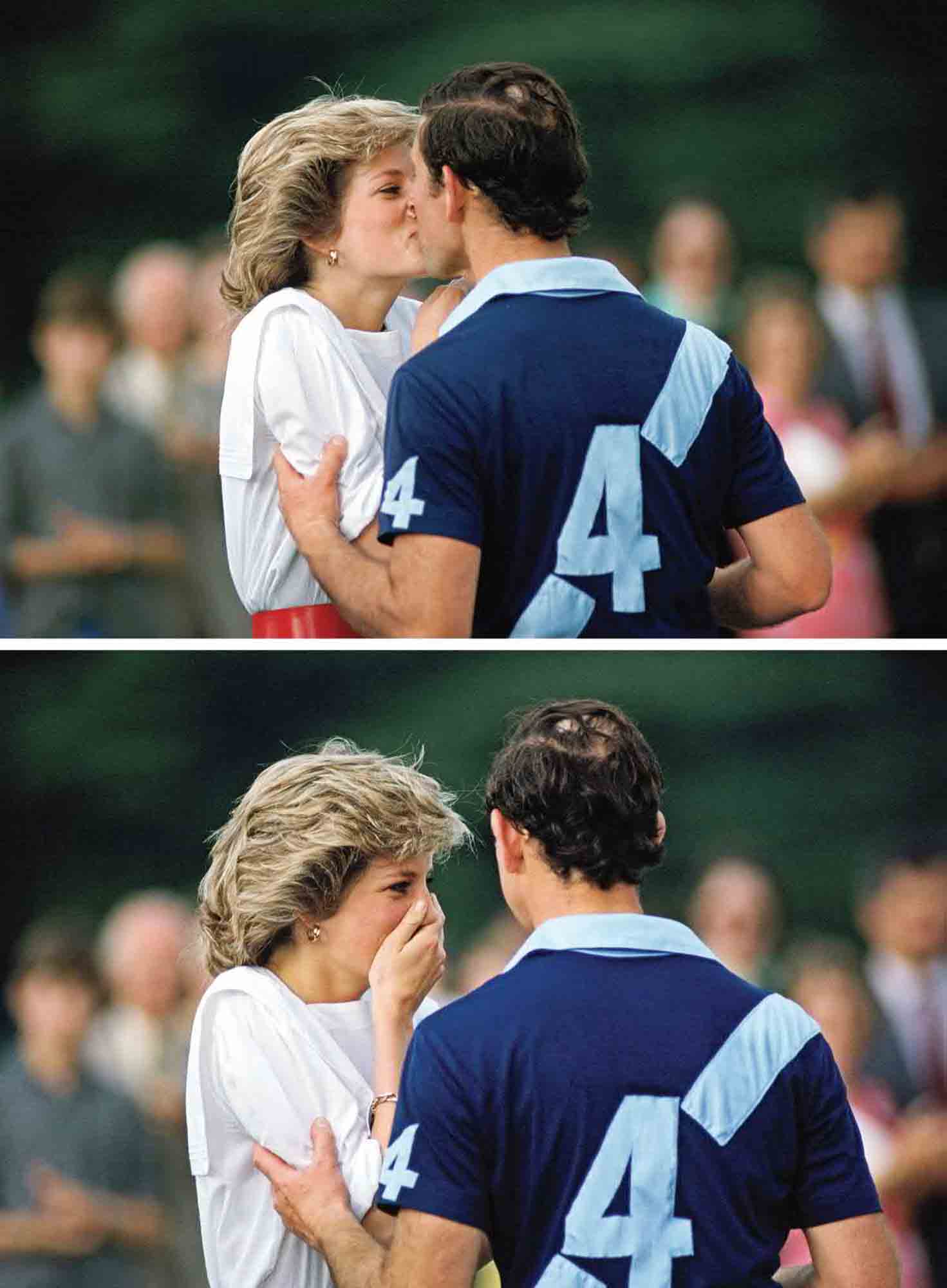

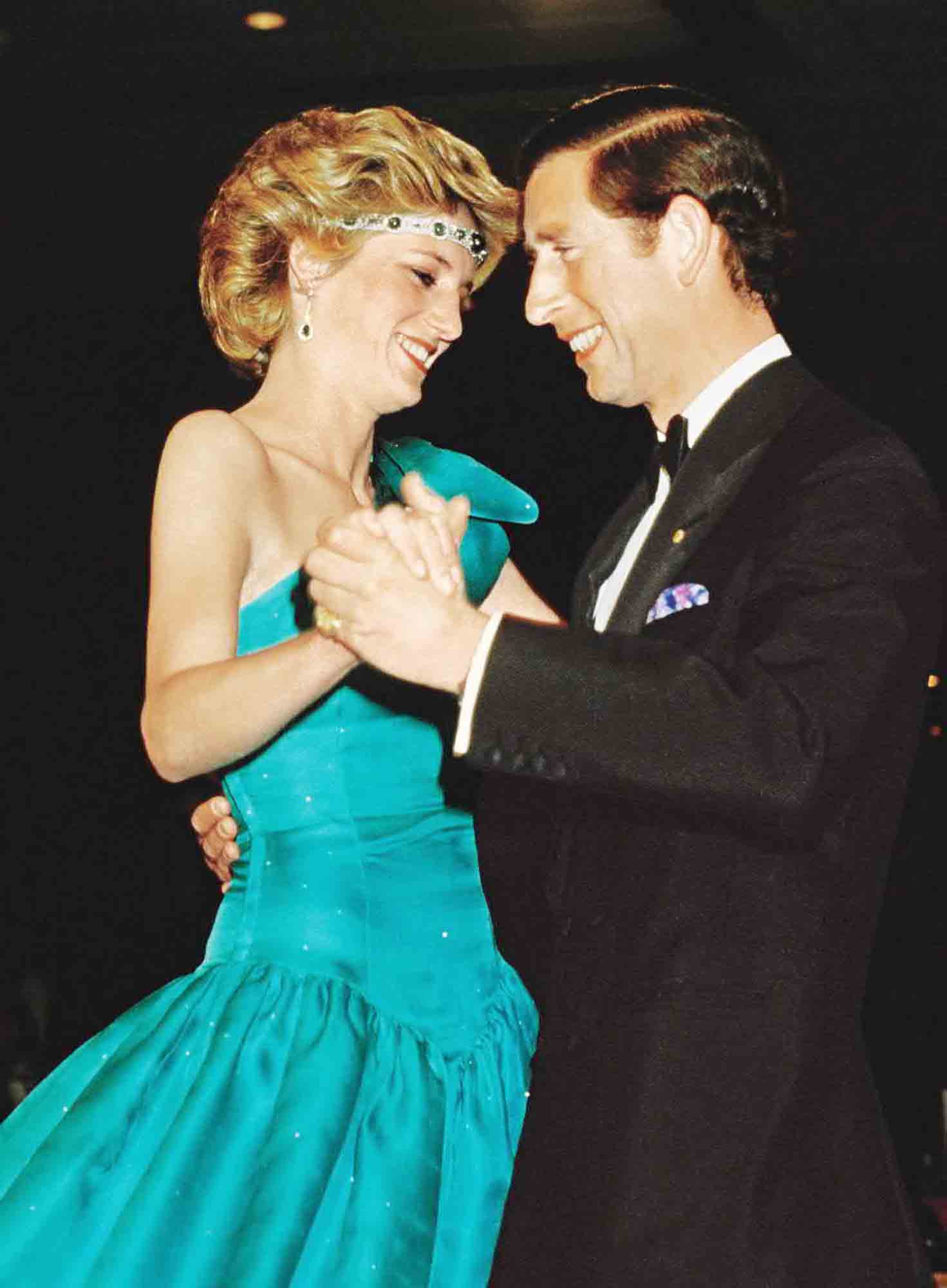

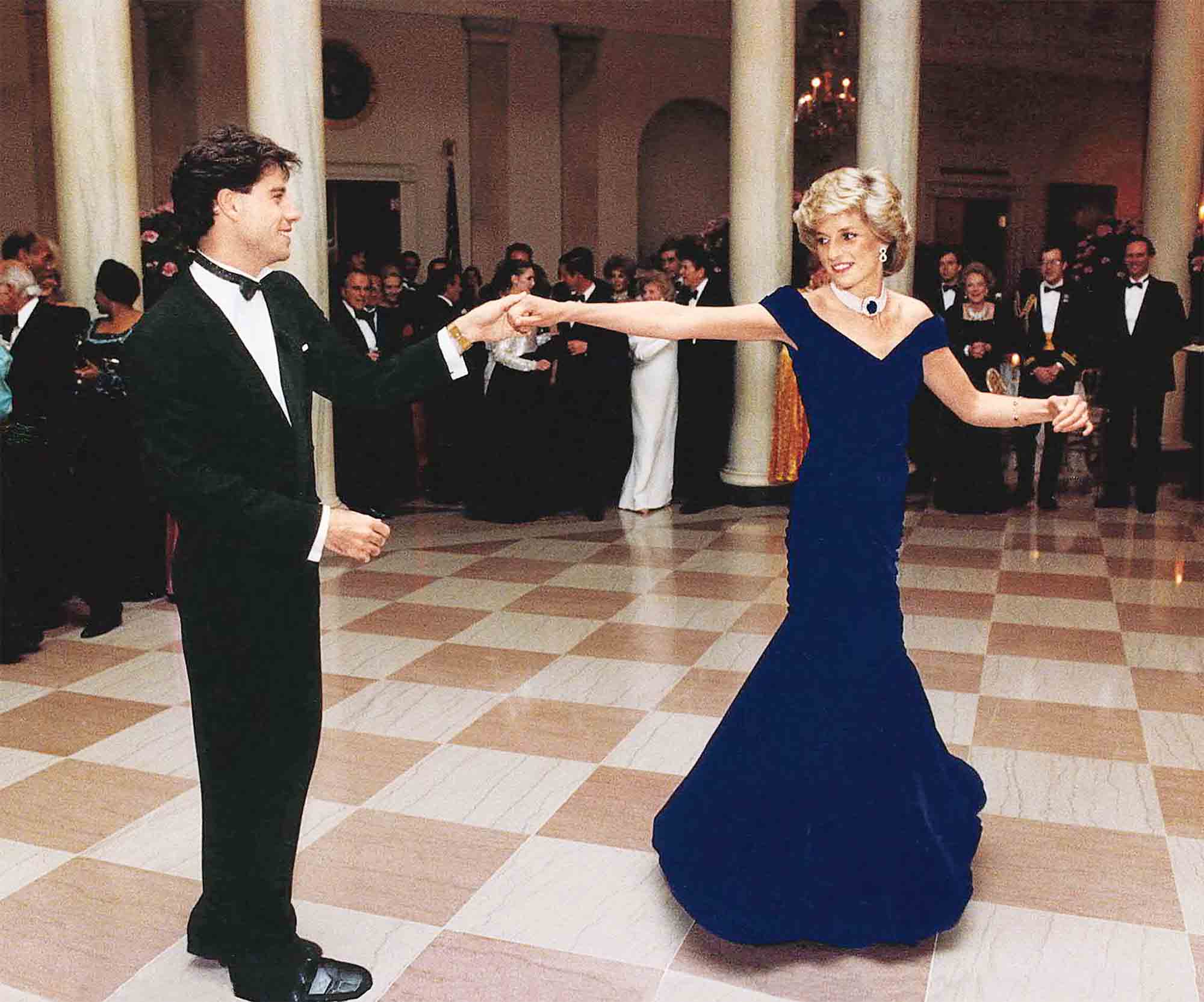

Shall We Dance, Part I

We see several pictures from 1985, one of which, perhaps, made Prince Charles happy.

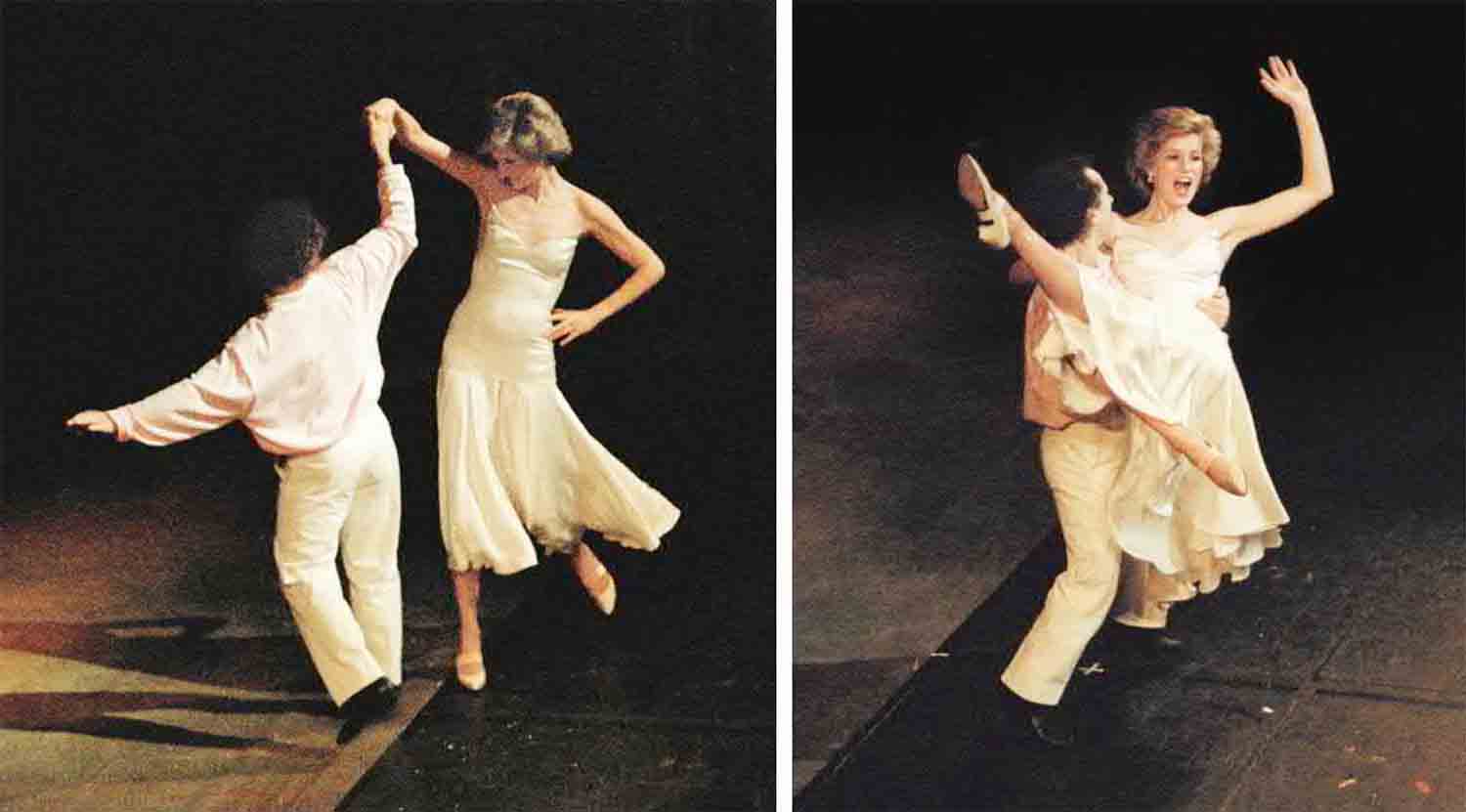

Shall We Dance, Part II

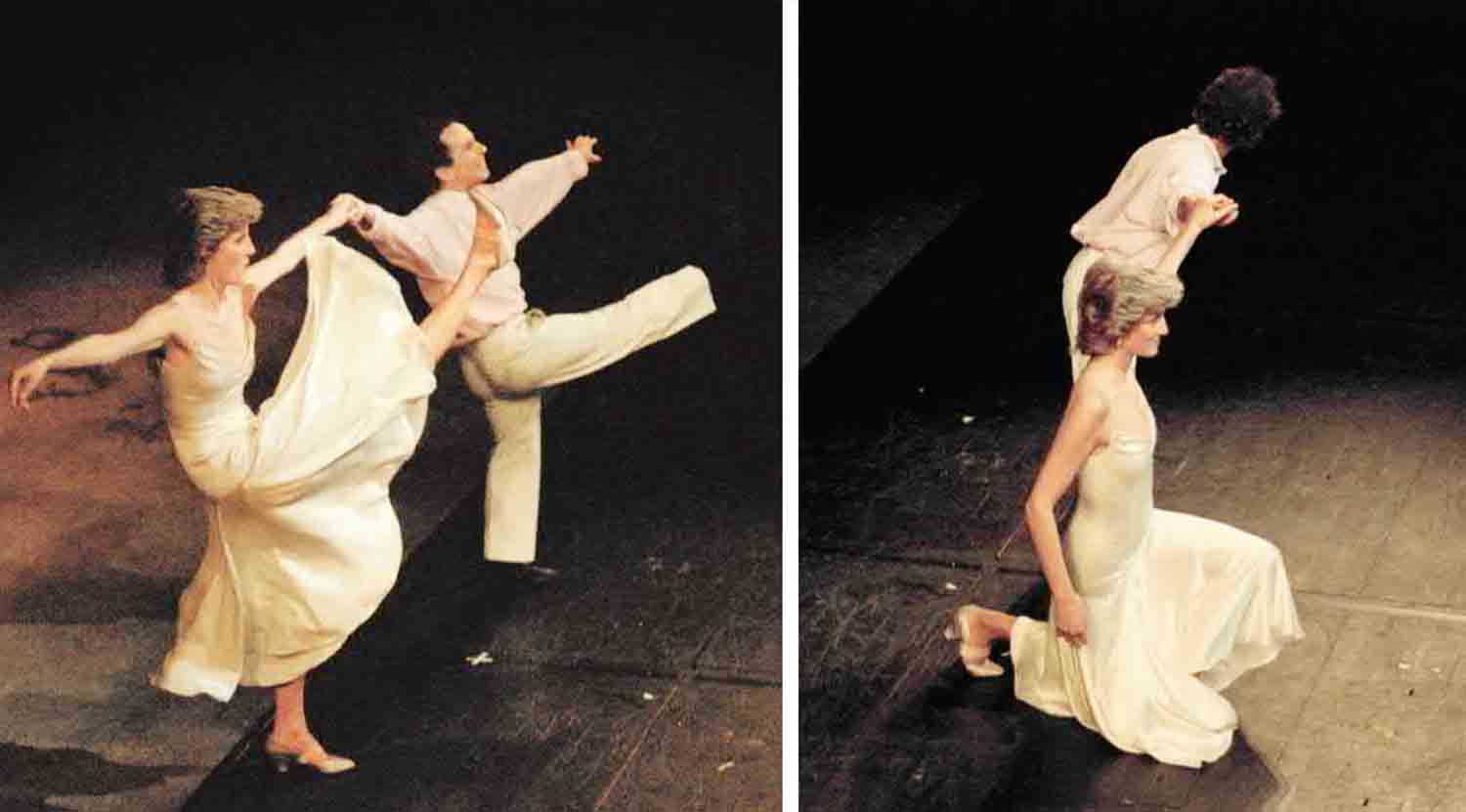

Shall We Dance, Part III

Even Harry’s baptism in 1984, a celebratory event, put Windsor discord on public display and showed Diana in a me-against-them posture. The backstory: Charles was (and remains) close to his sister, Anne. Diana had few to no friends or allies in the royal family, and her relationship with Anne was sometimes chilly. People magazine, which had reported on William’s christening with nothing but touching tenderness, was compelled to cover Harry’s thusly: “In London at year’s end, it was the English royals— once models of at least surface harmony—who seemed woefully besmirched by bad tempers and rifts. In their fashion, of course, they struggled to be mum and mollifying about it all. But nothing could quite hide the rather awkward truth: While three-month-old Prince Henry Charles Albert David, third in line to the British throne, was ceremoniously baptized over a Victorian gilded lily font by the Archbishop of Canterbury in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, his Auntie Anne and her husband, Capt. Mark Phillips, were out shooting in the countryside, bagging rabbits.

“The real field day, naturally, was in the British press, which turned Anne’s snubbing’ of her nephews christening into an apocalyptic—and apoplectic—event. How, they fumed, could Anne send her children, Peter, 7, and Zara, 3, but stay away herself? A feud in the House of Windsor, rumored for months, had finally erupted for all to see, crowed Fleet Street. Whiffs of grapeshot were first reported last October, when Prince Philip was said to be annoyed with Charles’s lack of regard for his sister. Anne, 34, had not been named one of Prince Williams six godparents at his 1982 christening. According to one senior royal aide, ‘Prince Philip was very hopeful she would be chosen this time.’ Yet when the list of Harry’s godparents was published on Nov. 15, Anne’s name was not among them.”

Philip’s ire (reputedly a daily thing) might have been directed at Charles in this instance, but really this was just the latest episode in Diana v. Windsors going wide. And neither Philip nor Anne nor Charles was ever going to leave the family. Only Diana could, and insiders were starting to murmur that one day she might.

That day would not arrive—not technically, at least—for more than another decade, a decade that would involve a whole bunch of bad behavior, a multitude of bitter accusations, a million headlines, many books and much, much pain. Charles and Di began to lead largely separate lives before their marriage was five years old, but they also chose to soldier on. Finally, in December 1995, Queen Elizabeth had seen and heard and read enough, and advised her son and daughter-in-law to divorce.

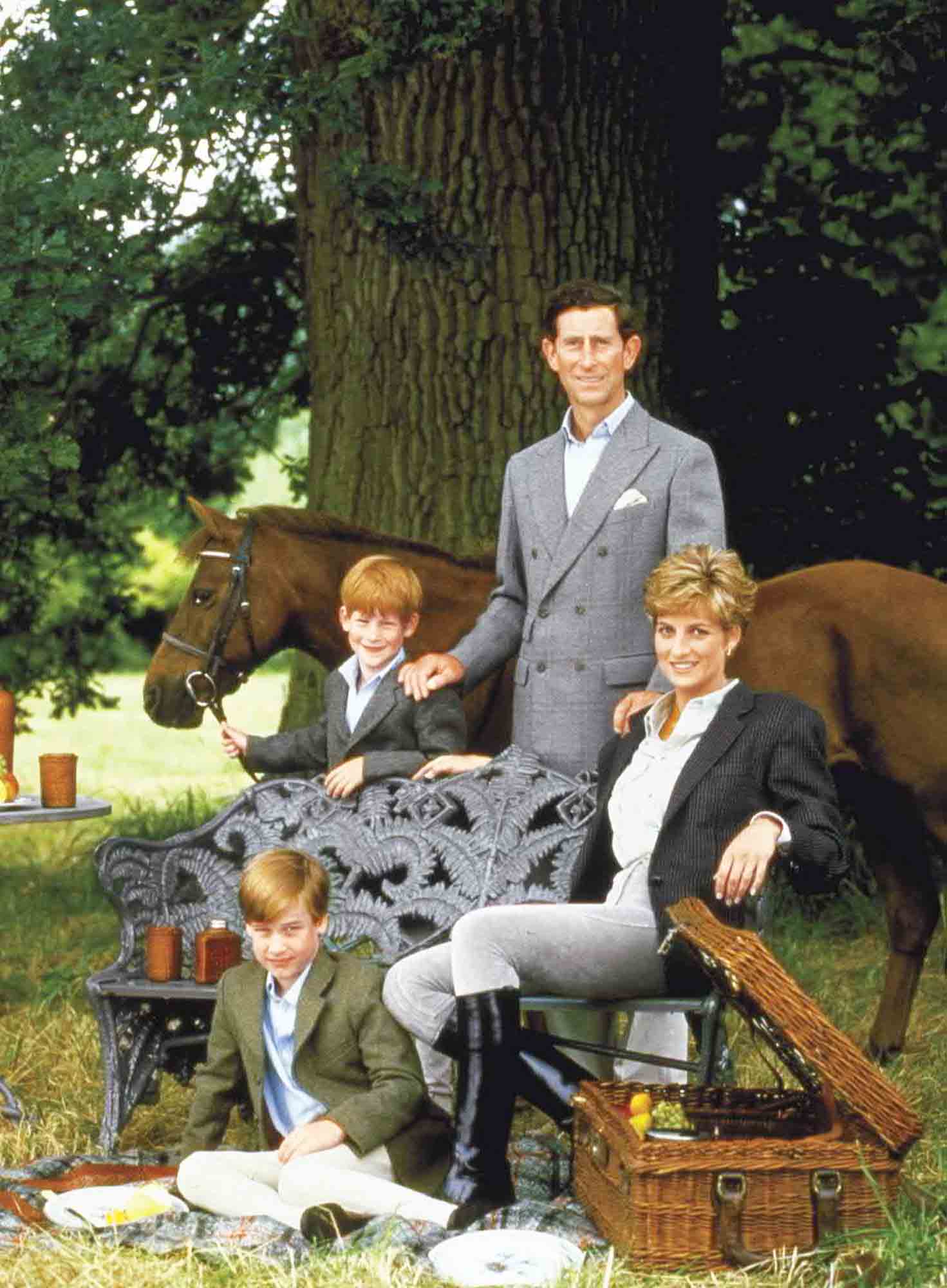

But in the intervening years, of course, there were the boys to raise. Both parents loved their sons. What to do about that?

It has become increasingly clear in recent years that Charles is a devoted father, but credit for Wills’s and Harry’s upbringing goes to Diana. Early on she asserted that she would be their mother in all ways. She chose their names. She dismissed a royal nanny and hired one of her preference (and it can be imagined how that went down with Philip and Elizabeth!). She dressed her sons, planned their birthday parties and playdates, selected their schools, and escorted them to class as often as she could. She tried to remake her own busy schedule of talks, hospital visits and ribbon cuttings with an eye to their needs.

The kind of proactive mothering she displayed was unprecedented in royal history. She took them to McDonald’s so they might feel like regular kids, and then she dragged them along on her visits to hospitals in the hope that they might learn about civic responsibility, and also absorb some of her sense of empathy, which by now was legendary and which she accepted as a talent. The visits to the burger joints and sick-kids wards had the desired effects.

As for royal and/or Windsor tradition: Diana didn’t seem to be very concerned with it. It’s too much to say “she couldn’t have cared less,” but if she was not overtly defiant of the Palace’s opinions when it came to Wills and Harry, she was often dismissive of it. The boys would not be circumcised, as British princes had been since time immemorial, and they would both attend Ludgrove School and, after passing their entrance exams, Eton College. Windsor lads did not go to Eton, they went to Gordonstoun. The boys’ father, Charles, had gone to Gordonstoun, as had their grandfather, two uncles and two cousins. But Diana’s father and brother had both attended Eton, and so would her sons. In short: Wills and Harry were educated as Spencers, not Windsors.

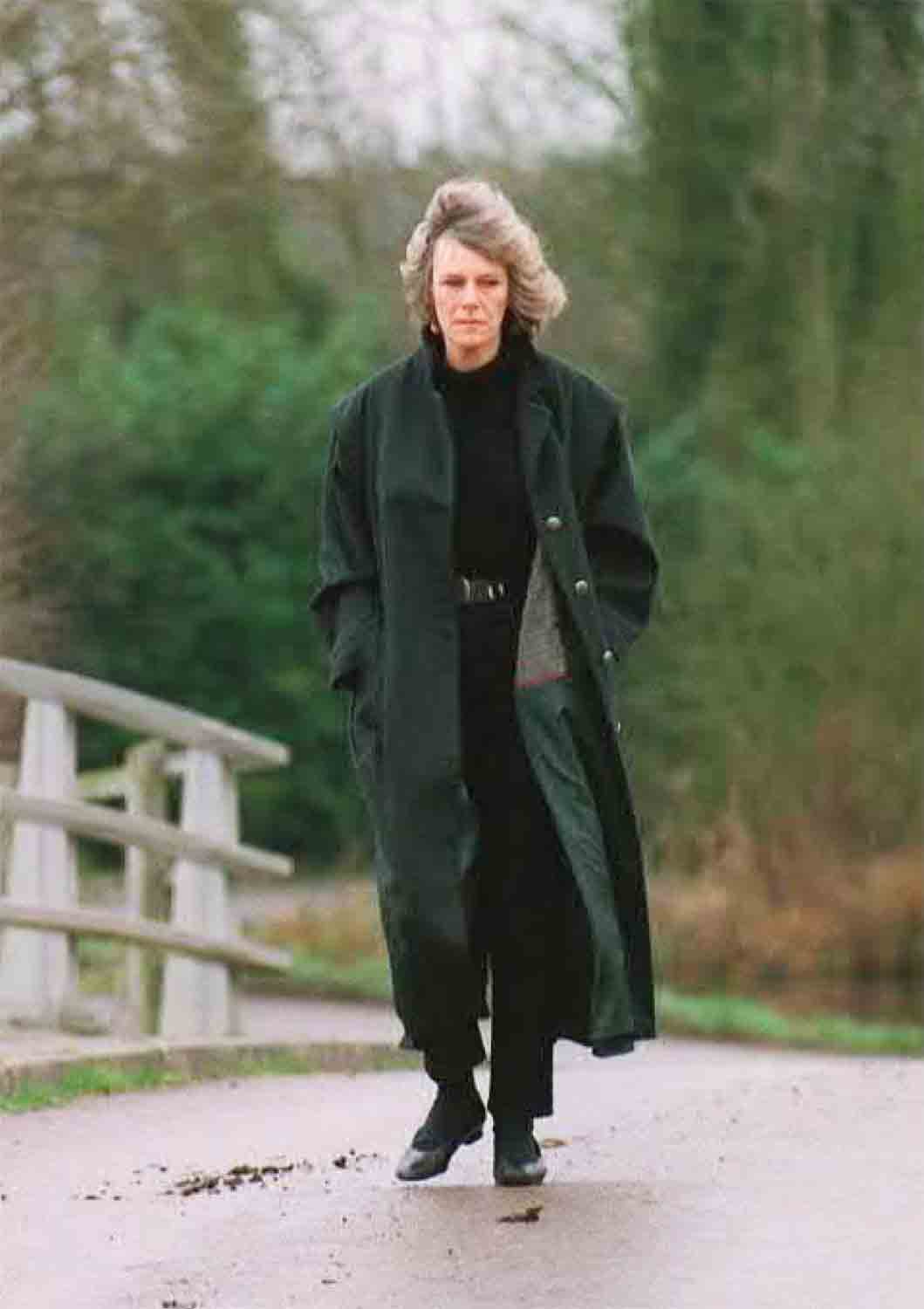

There is some question as to whether Diana’s bodyguard Barry Mannakee, seen here in 1985, was her lover, but there is no doubt that he died in a motorcycle accident in 1987 and the princess suspected foul play.

Diana’s behavior, if not purposely rude, was revolutionary and insurrectionist. To reiterate the point: No royal mother or father, ever, had deigned—no one had ever stooped—to raise a royal kid in such a hands-on fashion. (Diana winning prizes in the mothers’ footrace at her children’s school’s field day, for pity’s sake.)

And then, good grief, it seemed to work!

The boys progressed beautifully, no matter how hard prying eyes tried to find fault with other them or their otherwise increasingly tabloid-popular mother. Their boyhoods were as normal as possible. The best the paparazzi could do for the longest time was file photos of Diana wiping ice cream off her sons’ lips or of Mom and the kids on a ski vacation in the Alps. Wills, clearly, was as solid as the stone of Buckingham Palace; he was smart and handsome, destined to grow into something of a British JFK Jr. Young Harry was a bit of a roustabout, even when Diana was still alive, more into sports and tomfoolery than his studies. The brothers continued on their respective courses after her death: Wills, as said, racked up the best grades at university of any British royal in history (and the university in question was the august St. Andrews in Scotland, where, as also said, he met and fell in love with his eventual wife), then began his military career. Harry managed to pass a couple of A-levels at Eton, but pulled a D in geography while apparently majoring in polo and rugby. In 2005, he thought it would be humorous to wear Nazi garb to a costume party, which only pressed home for him (his mother certainly had warned them both!) that there are cameras everywhere—everywhere!—when you are an heir to the throne. That tabloid storm eventually quieted, and Harry’s reputation would be largely redeemed with his service in the British army, in which he saw action on the front lines of the war in Afghanistan.

As the world watched the brothers perform so attractively at William and Kate’s wedding in 2011, the general response seemed to be: “Good boys. Their mother’s sons, of course.” Whether this bothered father Charles at all—and he certainly looked nothing but proud that day—it must have been noted by Elizabeth and Philip, who had always taken the general acclaim for Diana’s renegade, modern mothering as an affront, an implied criticism of their own traditional, cold-fish, hand-shaking manner of raising princes and princesses. The queen and her consort must have heard the readers of the Daily Mail sneering, “Well, look how Charles turned out compared to these two wonderful young . . .”

Three things bolstered Diana’s public persona in the years that her marriage s fairy tale facade faded and as the transgressions of both partners were revealed one after another: her status as “the first one wronged,” her reputation as an exemplary and loving mother and her dedication to helping the less fortunate.

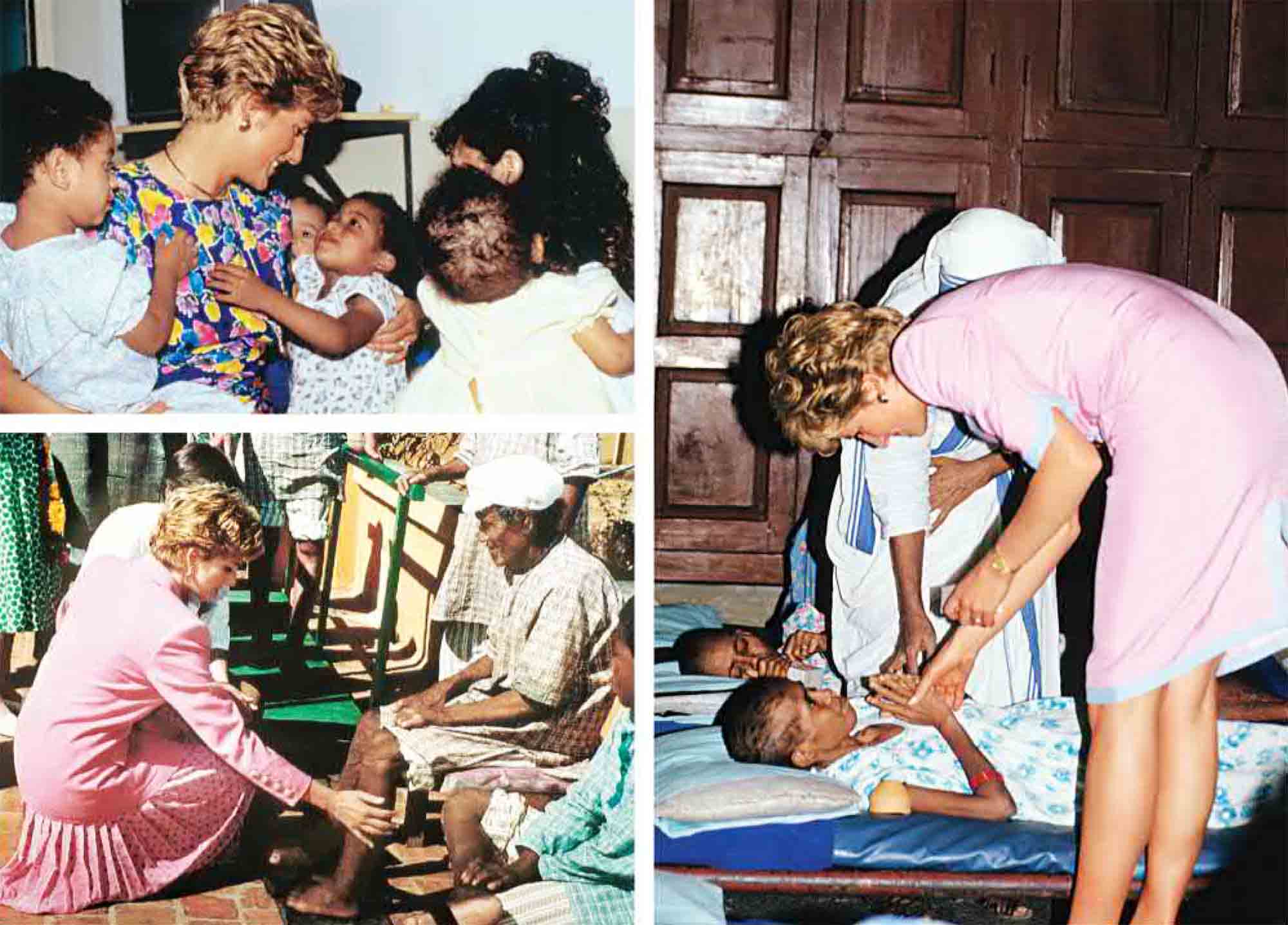

The royals are always involved in philanthropic and humanitarian enterprises—it comes with the job—but they are just as always involved at arm’s length, supporting charitable institutions and giving the haughty wave during hospital visits. Diana, by contrast, could never have told you how much money the Windsors had contributed to a given cause, but she could describe in detail her encounter with the young, very ill girl with whom she had just exchanged a bedside kiss. She found her best self, exercised her best talents and cemented her relationship with the watching world by reaching out.

Some celebrities choose a cause because they feel, perhaps rightly, that they can accomplish more by focusing tightly: Bob Geldof and Ethiopian famine, Elizabeth Taylor and the fight against AIDS, Bono and Third World debt, George Clooney and Darfur. Diana didn’t discriminate (and, it is not unfair to say, never really focused until late in her life, when she singled out the victims of hidden land mines as an issue—an issue that, certainly in part due to her high profile and dedication, would be acknowledged by the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize). Given the choice between fighting malaria or fighting drought, she might be conflicted (but she would enlist to fight both). Given the choice between a hospice visit or a night at the opera, an audience with Mother Teresa or a meet-and-greet with some grand duke from one or another vaguely Germanic principality—well, her decision here was obvious. And, to the mind of Buckingham Palace, a bit bizarre.

Like Taylor, she became a champion of AIDS awareness. She worked to combat the scourge of leprosy. She assumed, in 1989, the presidency of the Great Ormond Street Hospital, an institution for children. This might have been the most meaningful of the many titles she held as princess, and she held it until she died. She traveled to refugee camps and soup kitchens. She fed the poor herself, holding the spoon. She was awfully good at what she did in this realm, and since a camera was ever-present, everyone, everywhere saw it—and was able to see the honesty of it.

So as a princess she was beloved as no other princess outside of fiction ever has been. But the final train wreck in her nonfictive personal life was rushing on, and in the early 1990s it occurred, as if seen in slow motion, hit by hit, screech by screech.

The tabloid stories about her lovers and Charles’s return to Camilla were already on the table. But in a way, it can be said that it was Diana who declared war—or launched the first battle of the war’s final stages. In June of 1992, Andrew Morton published his (and Diana’s) biography, and her side of the story was now on the record. Charles’s agents responded “off the record” or “not for attribution,” and any rules of decorum were abandoned. It was no-holds-barred from here on in. This was true for Fleet Street as well, of course, which had earlier made it clear that it was happy to flout such rules that others might think—ha, ha—still existed. The tabloid hounds started sniffing for ripe material, obtained by any means, and came up with plenty.

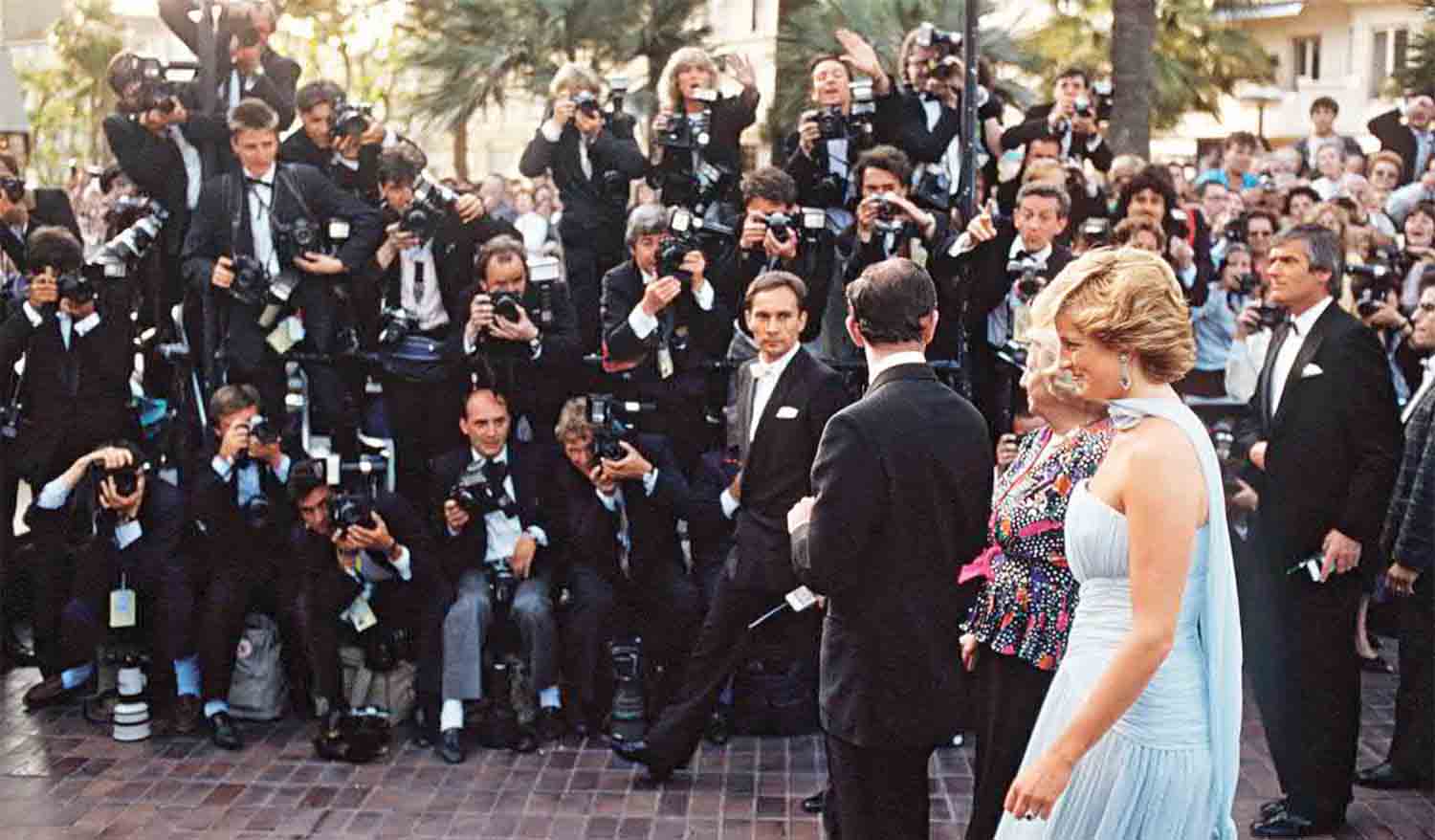

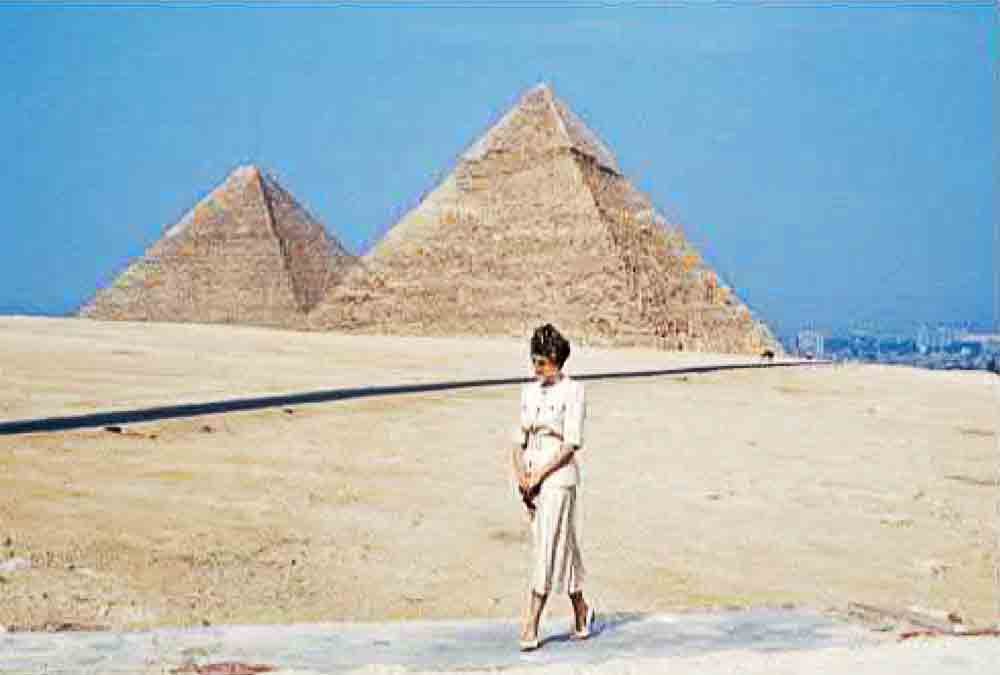

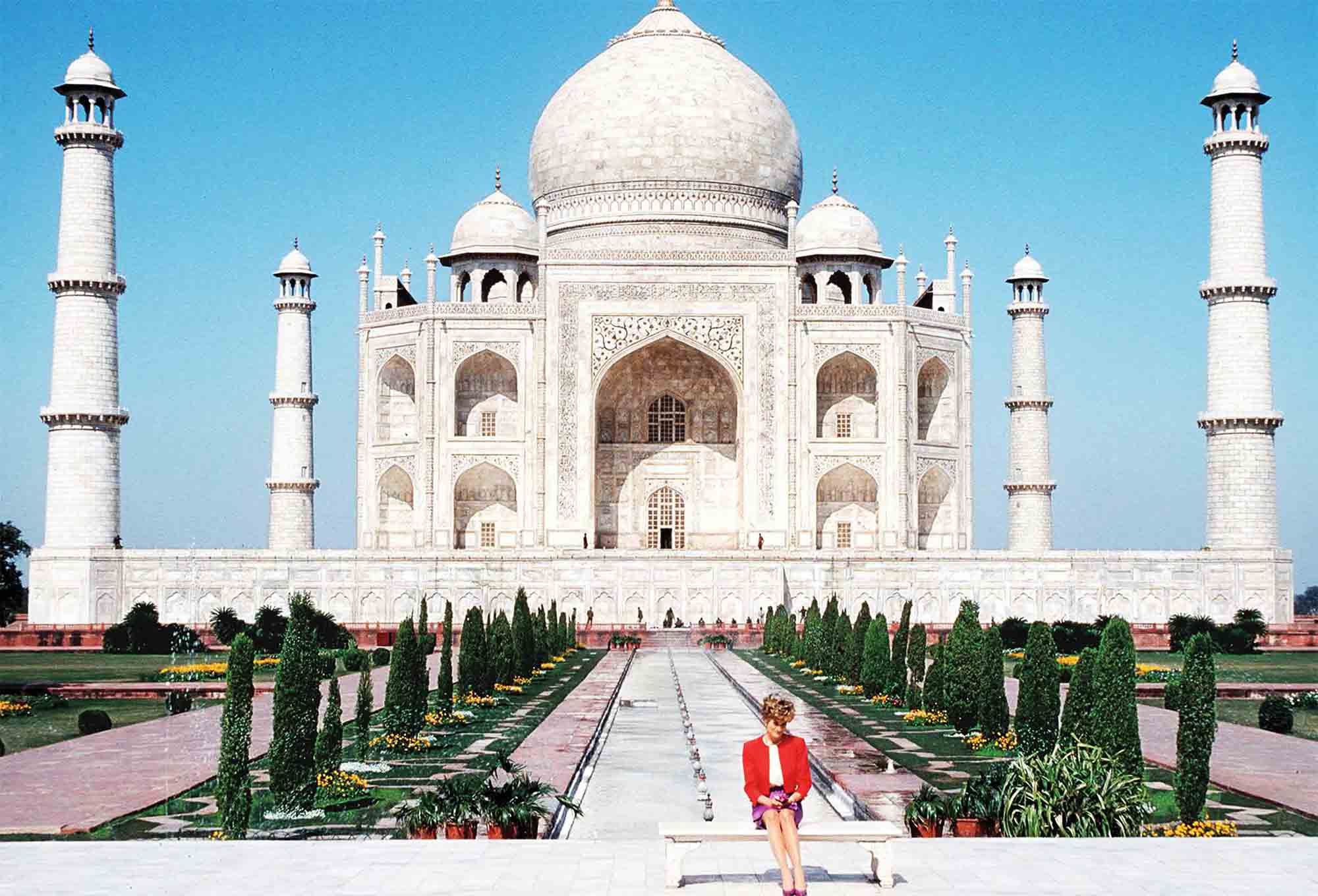

The rift in her relationship with Charles was sufficiently longstanding that she often went her own way even when traveling with him; once liberated by their announced separation, she continued as Great Britain’s top diplomatic superstar.

If 1992 was, as Elizabeth II declared in a speech that November, the queen’s personal annus horribilis,” it was nothing less than that for Charles and Diana. What happened that year:

— In March, Charles’s brother Andrew and his wife, Diana’s wild-child pal, the former Sarah Ferguson, called it quits on the heels of the publication of topless photos of Fergie.

— In April, Princess Anne, Charles’s sister, divorced Captain Mark Phillips.

— In June, Diana, Her True Story was published, detailing multiple infidelities in the Wales household.

— In August, taped conversations between Dana and her lover James Gilbey (the so-called Squidgygate tapes, after an affectionate nickname Gilbey has bestowed on Her Highness) were published in The Sun.

— In November, Charles’s Camillagate tapes,every bit as embarrassing as and even more graphic than the Squidgies (I want to be your tampon), were transcribed in two other newspapers, Kent Today and the Sunday Mirror.

— That same month, a major fire severely damaged Windsor Castle and claimed many of the family’s priceless artifacts.

— Finally, in December, Charles and Diana officially confirmed what everybody already knew: that their union was no more and hadn’t been happy for a goodly while.

Their announced separation after their years-old de facto separation did nothing to dim the spotlight. Paparazzi hounded Charles and Camilla daily, and doubled up on Diana and her new boyfriends.

Why the Waleses carried on for four more years—through increasingly brutal sequences of recrimination, embarrassment, and verbal and psychological assault, through further adulterousness, through a growing mountain of physical and emotional distress (for Diana, through many more episodes of bulimia), through periods of interpersonal battle that took a toll on their dear children—can only be ascribed to animus, or to the bogus “permanency” and “tradition” of the monarchy.

Consider: Even the great scandal of Edward VIII, which led to his abdication in the 1930s, didn’t have to do with anyone divorcing him or him divorcing anyone, but with him wanting to marry a divorcee. The travails of Charles and Diana seemed, in the 1990s, much more consequential. Surely British princes and princesses had divorced in the past. Charles’s Aunt Margaret comes immediately to mind. But first-in-line heirs to the throne had never been caught up in the kind of thing that Charles was caught up in—a thing he hadn’t ever wanted and actually might have avoided, given a choice.

But it had come to this, at long, exhausting last, and on August 28,1996, the Prince and Princess of Wales divorced, with Diana receiving a lump-sum payment of more than $30 million. The settlement included a standard clause in royal settlements: that details of the marriage not be discussed going forward.

Of course, the contract, at least that particular stipulation, had come much too late.

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE AUGUST 2017