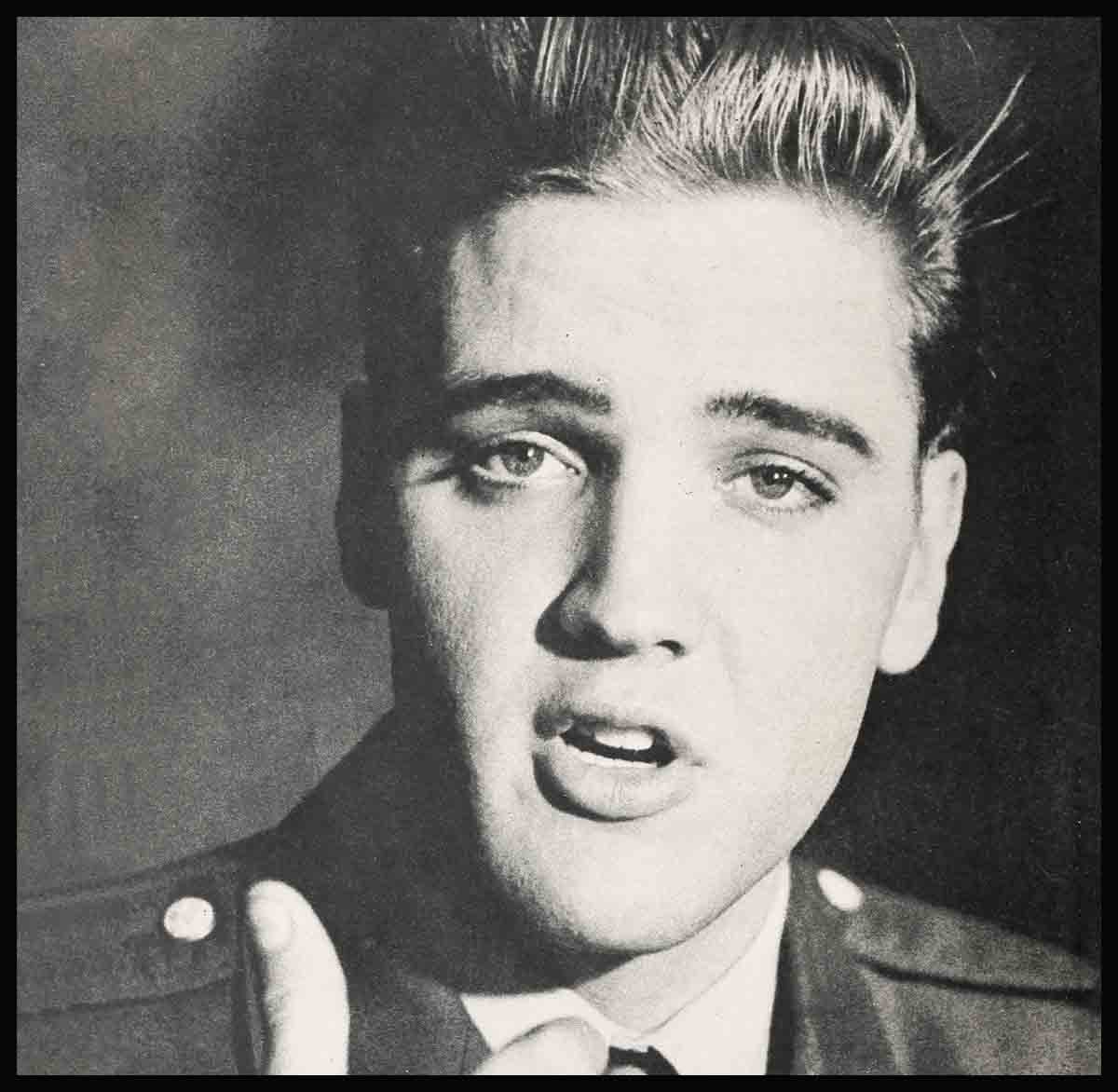

Don’t Rush Me!—Tab Hunter

Next to a successful career, there’s nothing I want more than to be successfully married.

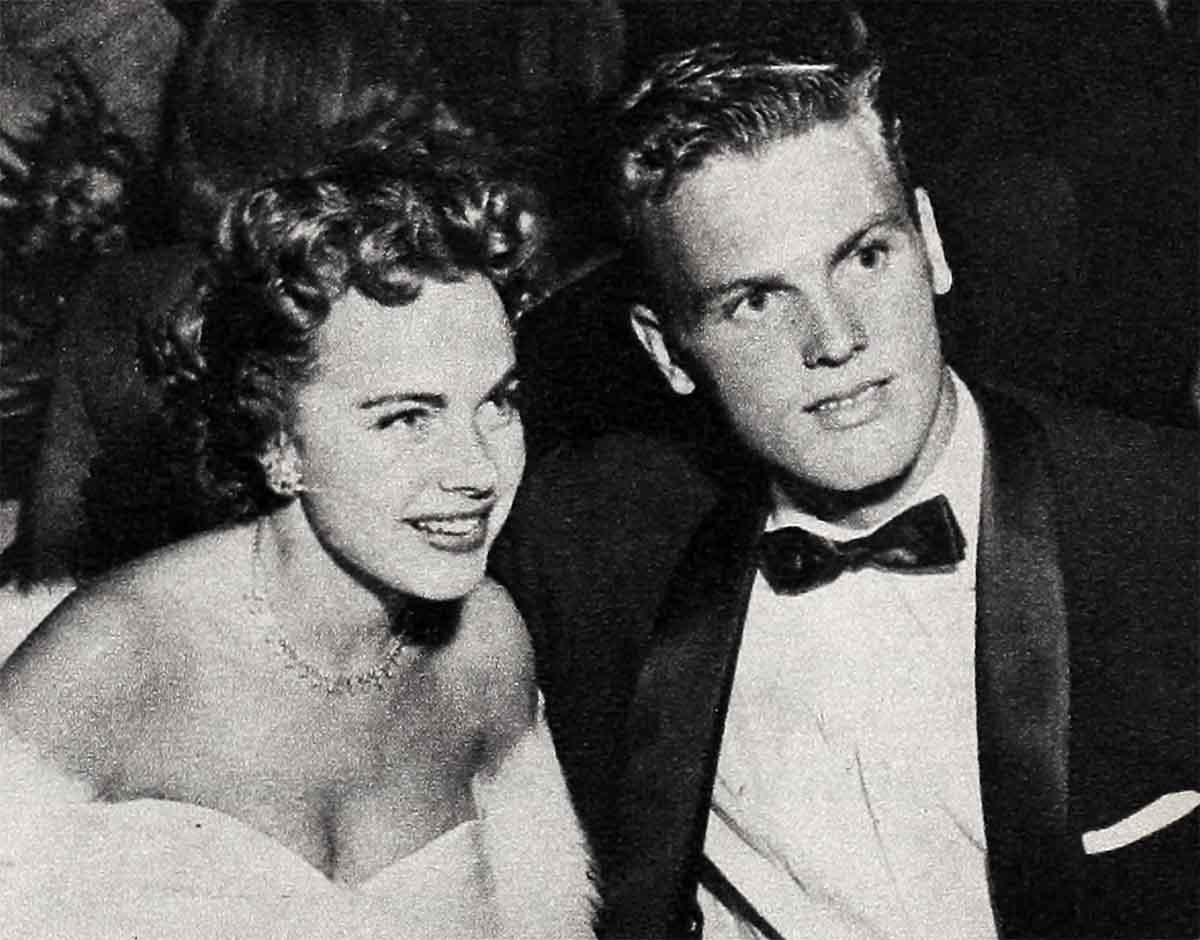

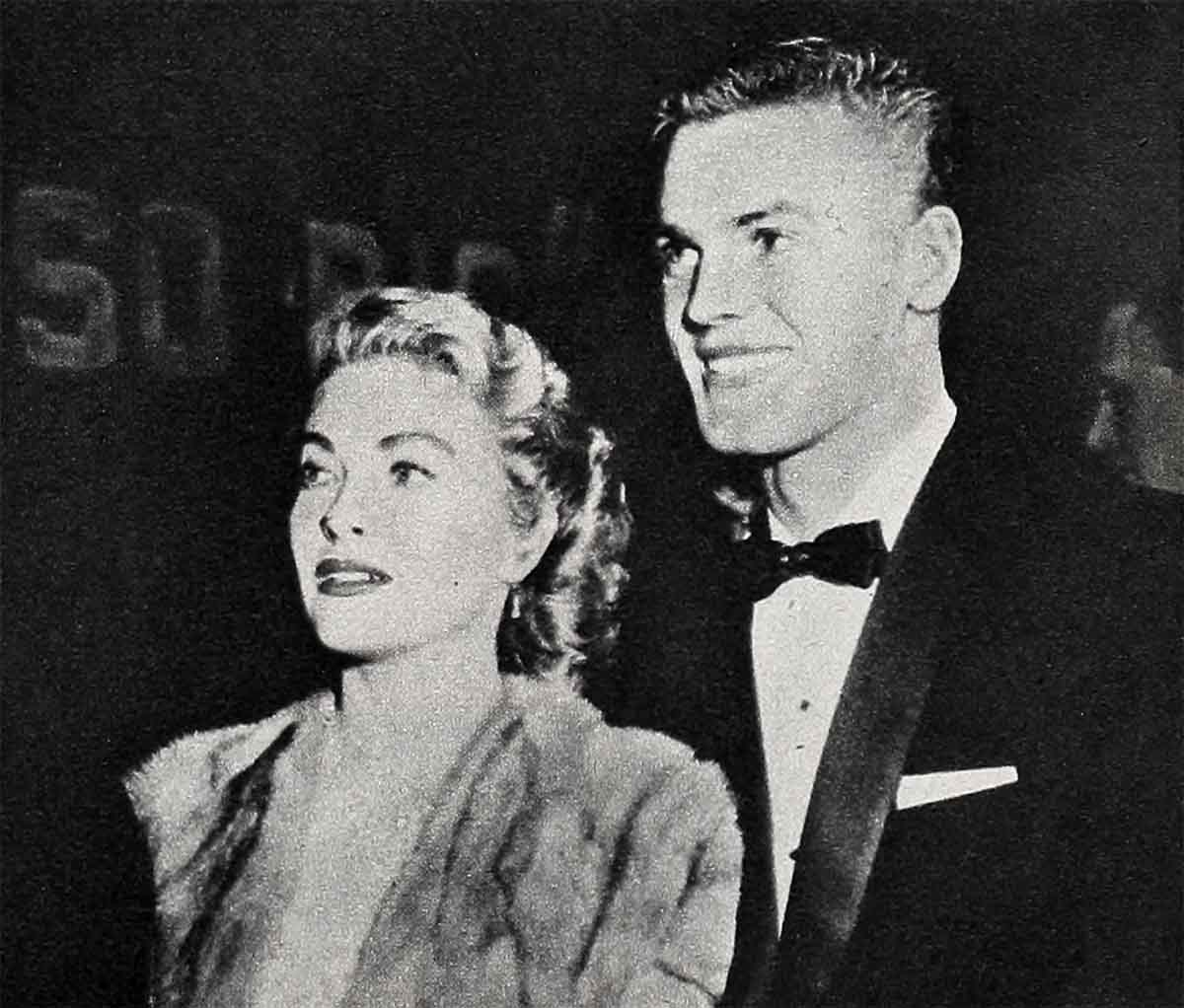

I no longer care for cooking my own meals nor enjoy eating out all the time; I can do without night clubs and premieres and although I have a good time dating such wonderful girls as Debbie Reynolds, Lori Nelson, Terry Moore and others, I’d much rather settle down with one girl—for good.

Why, you may ask, haven’t I married if that’s the way I feel about it? Not having found the right girl is one reason. Another, just as important, is that I’m simply not ready for marriage.

Not that I haven’t been in love. That’s one of my troubles—I’m always. in love!

Starting with a crush on Mary Lou Valpey—when I was twelve—almost every time I met a new girl I fell for her like a ton of bricks. Sometimes I was impressed by her appearance, other times by her intelligence, mostly by an accomplishment of one sort or another—whether it was horseback riding, skating or acting.

In that respect I haven’t changed and am not likely to do so in the immediate future. And since I can’t be sure that my feelings for any particular girl will endure, it’s best for me—and her—to boil my own coffee in the morning for the time being.

Sometimes I wonder why I’m unable to concentrate on just one girl for any length of time. A psychiatrist-friend of mine told me that it might be a matter of self-defense on my part; that I know I shouldn’t get married at this time, and consequently, every time I get serious about a girl, subconsciously I start looking for someone else. . . .

Be it what it may, it doesn’t make for permanence.

Another reason for staying single is my age. At 23, I feel I’m too young to get married, that for me, the late twenties would be a better age for matrimony.

Not that I feel that all the fun stops once I say “I do,” that I’ll be bound to home and family in a way that’ll restrict any pleasure from there on in. But statistics, particularly in Hollywood, have proven that a marriage has more chance for success if at least the man is a little more advanced in years.

Moreover, there are a number of projects I want to accomplish before I settle down. Like completing my eighth figure skating test, the highest non-competitive honor an amateur can receive.

Practicing for these tests takes time, lots of time. When I’m not in a picture, I usually get up at five in the morning, so I can be at the skating rink by 7:30. Whenever I can get away—and sometimes when I shouldn’t—I head for the Arrowhead Mountains to practice at Blue Jay, one of the best rinks in California.

In the past, I’ve often been criticized for my enthusiasm for skating. I’ve been called immature and inconsiderate because I seem to put it ahead of my career. I can’t deny that skating has become a mania with me. But I know I’ll change once I make the grade—the final test. Why?

The answer is not easy to put into words. Probably it’s the same drive that makes men climb mountains, drive faster, fly higher. For generations, men have tried to conquer Mount Everest. We have been told that from a scientific point of view little can be accomplished by doing it. Yet many have lost their lives in the process because they wanted to prove it could be done—prove it not only to the world, but more important, to themselves.

Skating is my Mount Everest. It isn’t as dangerous as mountain climbing, but to me just as exciting and gratifying. I’ve got to get to the top in my class. Then I can relax.

Another obsession, if you can describe it as such, is my plan to build a house, my own home, before I settle down. Not in the city, but in the Arrowhead Mountains. Again you may wonder what that has to do with marriage. Possibly very little if I weren’t in the movies. Since I am—very much—let me explain.

I like Hollywood and am grateful for what it has done for me—career-wise. I’m a lot less fond of the social side, the insincerity, the artificiality I have found in many instances—and which several times already have threatened to destroy my own perspective. Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not trying to say that everyone in the film industry is insincere. Far from it. Only that someone like myself—young and comparatively new in the business—can easily succumb to many of the temptations of vanity and empty compliments.

Before I got into the movies, I was used to being frank with people and expected them to be the same way with me. That’s why I grew so fond of girls like Marilyn Erskine and Debbie Reynolds, who could take and give criticism no matter what the reaction would be. With both I know at all times where I stand. If they don’t like a suit I wear or consider the flaming-red color of my car too loud, they tell me so in no uncertain terms. They neither make up to me nor expect me to pay them phony compliments. But, I regret to say, Marilyn and Debbie are exceptions in a town that is built largely on the ego of the people who live in it.

There may be a reason, a good reason, for it. I was told that when an actor is too severely criticized, he might lose faith in himself. If that happens, not only his ego but his performance will suffer, and before he knows what happened he may be through.

Although I personally feel that “Battle Cry” is the first really good part I’ve ever had, most of the pictures I made before were not of the same calibre, and my performances mediocre, at best, I never walked away from a preview of any of my pictures where people haven’t exclaimed how wonderful I was!

I used to sneer at such an attitude, but not long ago I suddenly caught myself making the same type of compliment. That’s when I knew that unless I changed in a hurry, I might lose my self-respect.

Or take a look at the fuss that’s made about an actor during an ordinary working week: the parties, the limousines waiting to take him to and from lunch, the interviews, the clamoring for autographs and posing for pictures.

I know it’s part of the business and that when people don’t care any longer, an actor is through. But at the same time, unless he has a strong counter-balance, an equilibrium of some sort that keeps him down to earth, he’s through too. Maybe not as an actor, but certainly as a human being.

In the past, whenever I felt that I was coming dangerously close to falling into step, to paying false compliments and believing everything that was said about me, I simply got into my car and went for a long drive by myself. And when I got away from the city, driving along the ocean or inland through fields of alfalfa or rows of orange trees, once again I would see the world through the eyes of Art Gelien and leave Tab Hunter behind in Hollywood.

I have taken many such trips since I came to Hollywood. Up to now, it has been easy for me to just take off whenever I felt the necessity for it. But once I’m married, I won’t be able to pack up on the spur of a moment when I have to get away.

That’s why I feel a home away from Hollywood is not only important but an absolute necessity for me. My future wife and I could live there when I’m not working and come to town just when I’m in a picture. . . .

But a house takes more than plans (which have been ready for months down to the last little detail). It takes time to build—I want to do it myself—and last but equally necessary, it takes money.

The latter, unfortunately, is another very important reason why I’m a long way from matrimony. When I work, I earn a good salary, at least compared to what I made in the Coast Guard, as a gas station attendant and at the many other odd-jobs I had from time to time. But by Hollywood standards, I am far from being even halfway up the ladder.

Moreover, I don’t work regularly. During the past twelve months I was in front of the cameras approximately fifteen weeks and, of course, didn’t earn a cent the rest of the time. From what I make, more than half goes in the form of taxes, my agent’s commission and Guild fees. From the rest, in addition to supporting myself and paying off some old debts, including my car, I am helping my mother who has sacrificed so much for me for so long.

I know that every son has an obligation to his mother—but mine is much more than the usual. Since I was born, Mother not only had to carry the full burden of raising me, but even when she might have made it easier on herself by letting me help she refused to do so to give me more opportunities to enjoy my early teens.

For instance, when I was old enough to sell papers and run errands, it was harder for me to get Mom’s permission than it was to find a job. “I know a few dollars would help,” she used to tell me, “but you’re only young once and I want you to use your free time to have some fun. Go out and play with children your own age after school.”

Usually I would get a job on the q.t., for fear that she wouldn’t permit it. And Id only tell her about it when I handed her the money I had earned. More than once she made me quit so I could have some free time instead.

When I first started in pictures, the money I earned was so little I could have eaten only every third day. It was Mom—working as a physical therapist—who fed me the rest of the time, bought most of my clothes and paid my phone bill when the phone company shut off the service because I was behind in my payments.

Now you will understand why I want to take care of her before starting a house-hold of my own.

In recent months I have only been able to pay her doctor bills and get her a nicer apartment. Once I can afford to buy her a home of her own, I’ll feel that I have at least repaid enough of my obligation so that I can begin to look after some of my own interests.

And speaking about finances brings up another problem—my inability to hold onto money in the first place.

This weakness probably dates back to the hand-to-mouth existence I was used to for so long. Most of the time I didn’t have enough money to save anything anyway, and the few pennies I could put away once in a blue moon weren’t worth saving.

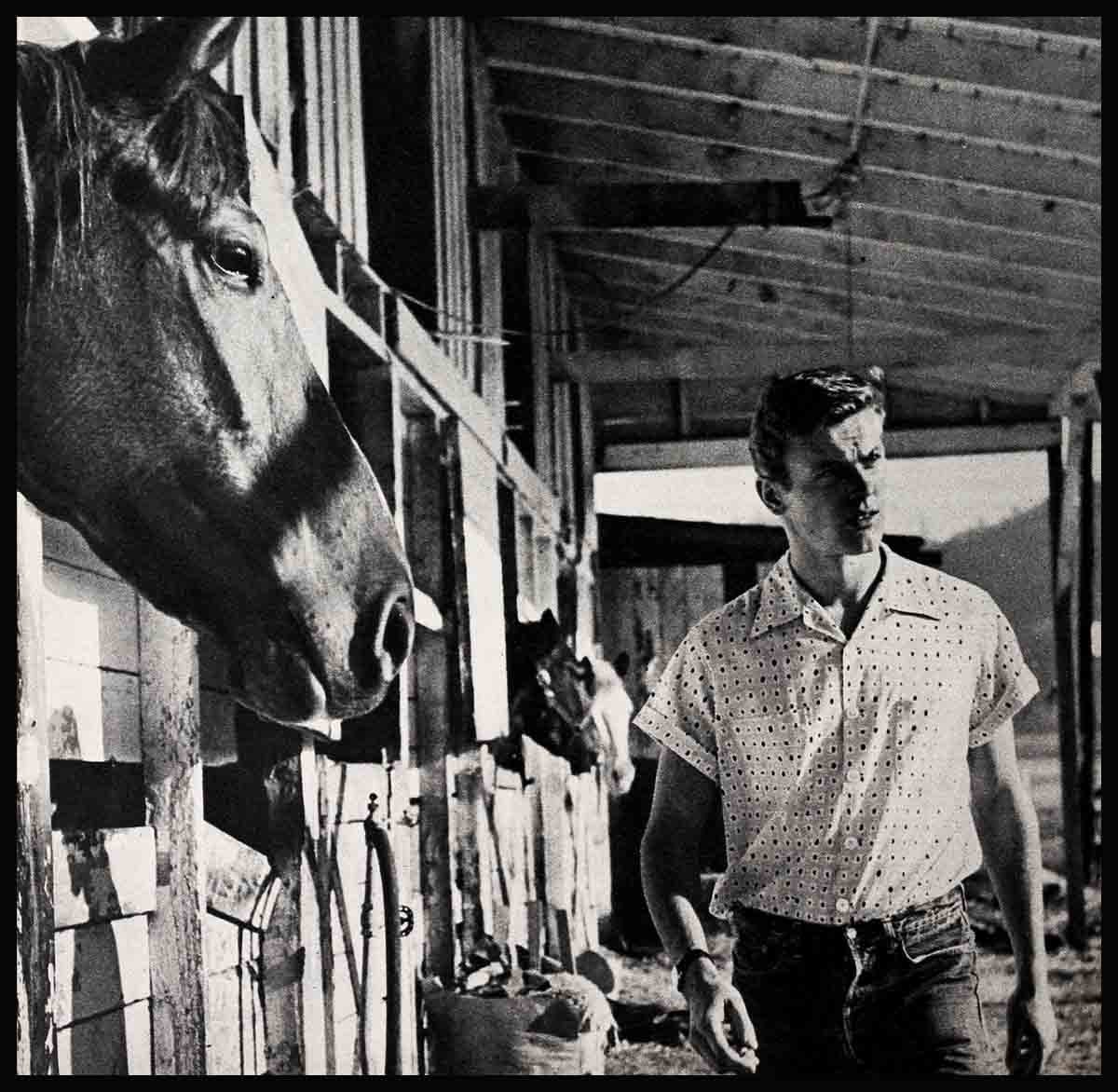

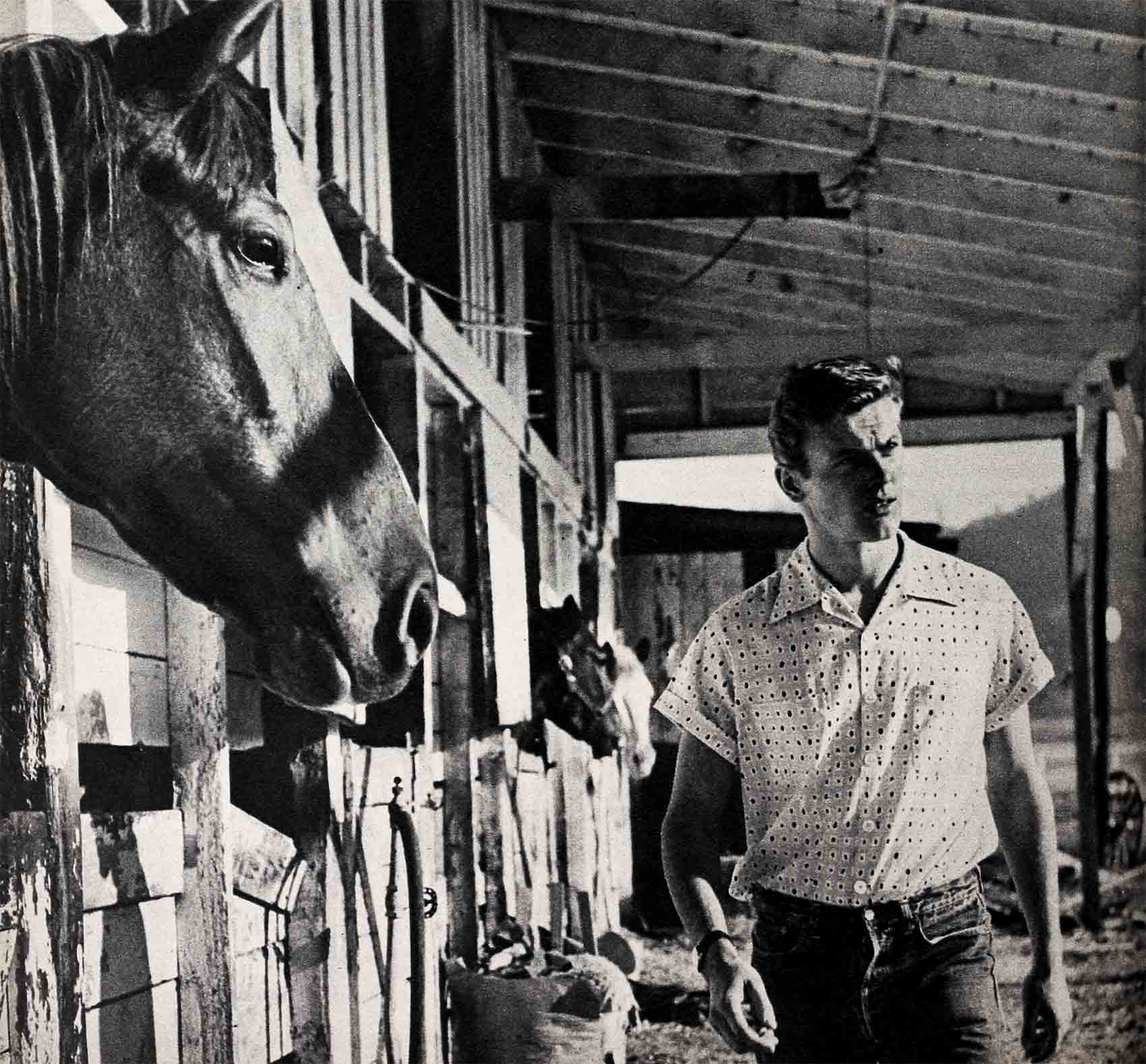

That’s why—when I made my first real money—I didn’t have the slightest idea how to plan a budget that would see me through the lean times. What did I do instead? Bought a horse—which I had to sell a few months later because I couldn’t afford to feed it! Purchased a new convertible for which I am still paying. Selected fifteen-dollar shirts when I should have looked for sales.

One evening, on the advice of a friend, I sat down and worked out a budget. After three hours, I patted myself on the back. There it was, in black and white: The amount of money I could safely depend on earning; the amount to be spent on regular monthly expenses; the amount left over for “extras.” I promptly put enough in my wallet for a week’s spending and deposited the rest in the bank. “I’ll be back a week from today with another deposit,” I told the cashier. “That’s when I get my next check.”

“We look forward to seeing you again,” she smiled politely.

She saw me, all right—two days later. And to withdraw, not to deposit. I couldn’t even remember how I spent my seven-day budget in forty-eight hours.

So I made up another, allowing myself a little more spending money. I don’t want to bore you with the details of my accounting, but I can tell you that I must have made up at least thirty new budgets in the past fifteen months—and stuck to none. But at least I can take credit for having made some improvement. Instead of going back to the bank the day after I deposit a check, today I often last almost an entire week.

Without excusing myself, I think poor budgeting on my part is not so much carelessness in spending money as poor organization—another habit I’ll have to lick unless I intend to drive any wife of mine to the verge of insanity.

As yet I haven’t succeeded in getting to places on time, remembering appointments or keeping up with my correspondence. I’ve tried all kinds of ways to help me remember. Like setting my watch fifteen minutes early to give me some extra time. That worked fine for about a week. By then I took the fifteen minutes into consideration in my original planning—and from then on was as late as before.

To help myself keep track of appointments, I kept writing little notes to myself. I left them on my dresser, pasted them on the wall, put them in the script, whatever book I was reading, the glove compartment in the car, dozens of other places. Needless to say, I couldn’t remember where I put the notes and after once spending a whole afternoon searching for one of them, gave that up as a bad effort.

A friend of mine made a suggestion that was to keep me out of trouble for good. “Get an answering service,” Dick Clayton advised. “That way people can leave messages for you, and at the same time you can always be reminded what to do where, when and with whom.”

The idea was great and has worked well as long as I remembered to call the service. But once—not long ago—I went through a whole week without inquiring about my messages, and not only came close to losing out on a film, but nearly missed a date with Debbie Reynolds as well.

I was supposed to take Debbie to a premiere the night I finally checked with my answering service. “Miss Reynolds wants you to pick her up fifteen minutes earlier tonight,” I was told.

“Holy smoke, I’d forgotten all about it.” Instead of rushing back to my bungalow in Brentwood, I rented a tuxedo and all the trimmings in Hollywood, threw them on the backseat of my car and raced right out to Debbie’s house in Burbank. Imagine her surprise when—all dolled up—she opened the door and found me in Levis and T-shirt. “This is not a costume party,” she said.

“I know. I’ll be ready in two minutes if I can use your bathroom.” And I rushed past her, into the bathroom to change into the tuxedo and ten minutes later was ready.

Any girl but Deb might have been annoyed. Luckily, she knows me. But how often would Debbie put up with it? How often would any girl?

And a final argument against marriage at this time is my overly critical attitude coupled with my sky-high expectations of any girl in whom I’m interested.

I have some pretty definite ideas of what I want in a girl, and while most of the girls I have gone out with in the past have one or several of these qualities—none had all.

For what am I looking? She should be attractive, but that’s really not all-important. She should be intelligent, understanding, a good sport, able to put up with my idiosyncrasies, enthusiastic about the sports I like and—while I want her to be a movie fan and understand my career problems—I don’t want her to be in the business herself!

Why? Because I don’t believe two careers mix and because I’m old-fashioned in one respect: I want to be the one to make the living. I want my wife at home to look after our home and the family I hope to have, and I want her to be free to travel when I can take time off.

Since I don’t want to marry an actress, I’ll have to mix more with people outside o industry. But I’m in no hurry to do that.

In addition to all other considerations, looking at it career-wise I am better off not married at this time. And since my eventual happiness will depend a great deal on my success in the movies, I have an additional reason for taking my time. First, I must get someplace as an actor. After that I can find a wife. For only then will I know I’m ready to get married—from all points of view.

THE END

—BY TAB HUNTER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1954

No Comments