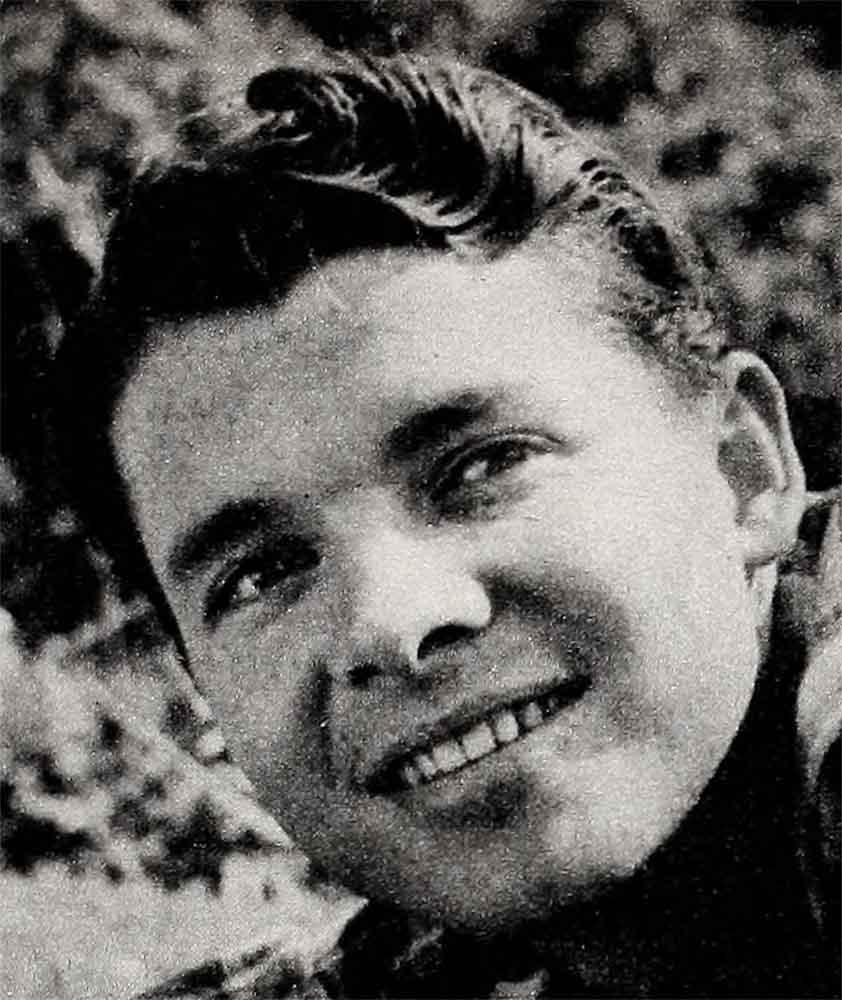

Lonely Joe

There’s an impression around that Audie Murphy hates Hollywood. It’s a false impression. He’s the kind of man who, if he hated Hollywood, wouldn’t be working there.

He enjoys the actual making of pictures, and wants to make them well. Failure in anything goes against the grain with him. “Kansas Raiders,” his latest, is the one he felt most at home with—because of the locale and Ray Enright, an easy natural director.

What disturbs him is the uncertainty between pictures. Clear and definite in his own decisions, he can’t live with uncertainty. Therefore, when a picture’s finished, he heads for the ranch of Ray Woods, a Texan friend, and stays till he’s called back.

It’s true that he fits into no Hollywood pattern, for which he condemns neither the town nor himself.

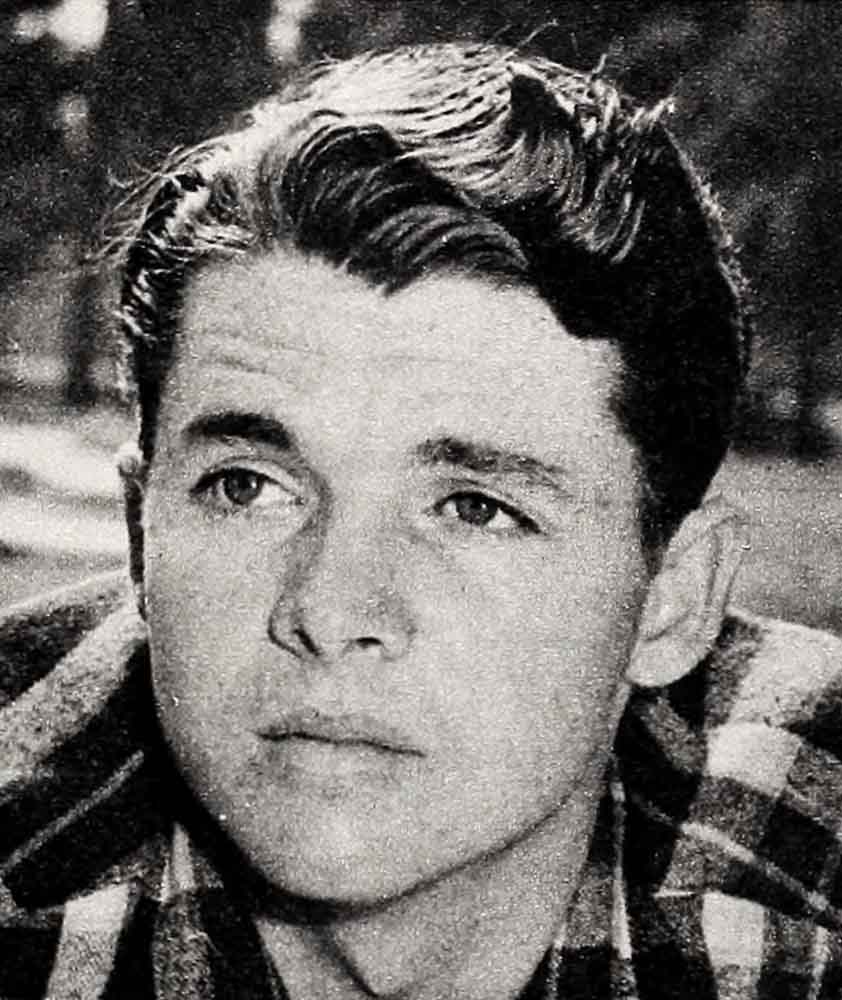

“To each his own,” says Audie. “I like horses and skeet-shooting. I don’t like the taste of liquor and cigarettes, so I don’t smoke or drink. I feel stupid sitting in night clubs like a wet owl. People don’t seem to realize that if you say no to the first drink, you’re going to say no to the second and third and fourth. Saves wear and tear on us all if I keep out.”

He’s been tagged a dour character, which he isn’t—though his humor, rooted in irony, is more likely to bring chuckles than belly-laughs. An ex-member of his Army unit still curses Murphy out for putting him on patrol. “Not me,” counters Audie. “I just volunteered for you.” Questioned as to whether he was going back to war, he said, “Sure. I’ll talk to General Hershey and see if I can’t get you in too.”

On a scene in “The Kid from Texas,” he kept asking for more rehearsals. Kurt Neumann, the director, grew impatient. “You’re okay, Audie. Let’s get on with it.”

Audie shook a doleful head. “I’m working under a great handicap.”

“What’s that?”

“No talent.”

John Huston apparently disagrees. He fought and won to get Murphy the lead in Crane’s “Red Badge of Courage.” Audio’s under contract to U-I. M-G-M felt that the plum should fall to a player of their own. What finally sold them, among other things, was a flood of calls from people who love the book. “The soldier’s real. Get a real soldier to play him.”

Audie loves the book too and wanted the part, yet half hoped he wouldn’t get it. His present unit was called up for two weeks’ encampment last August. Asking for a postponement bothered him. “Looks as though you’re not certain. I am certain. But some of the guys might not understand.”

He’s Captain Murphy now of the Texas National Guard, having enlisted when the Korean fighting broke out. “If the United States goes to war, I figure Texas’ll go too, and I want to be with a Texas outfit.”

Any hint that he may have done his share falls on dry ground. His closest G.I. friendship is with Perry Pitt, who came out of World War II a paraplegic. Pitt feels the need to go back. He knows he can’t but the need remains. “They could stick me into a foxhole and let me shoot. Save some other guy from being crocked up like I am.”

To many, this makes no sense. It makes fine sense to Audie. “For a country like ours, I don’t think you could ever do enough. I feel very strongly about Korea, and can’t understand those who don’t. Besides, it’s not just Korea. It’s survival for us and our kids and our whole way of life. Wherever we’re fighting, I might as well be there as anyone else. I’ve had the experience.”

On the other hand, he doesn’t flourish the flag. Loathing communism and fascism alike, he also recognizes the flaws in our own system. Flaws and all, he believes it’s the only system. He believes fiercely in what America stands for—freedom and human rights and dignity for all men. He believes that under the slow process of democracy we’ll achieve our goals. Though rated fifty per cent disabled, when he’s called to active duty, he’ll drop work and go.

Audie was the son of an unsuccessful sharecropper. His earliest memories are of working in the fields. He still doesn’t know the rules of baseball, since in his boyhood there was no time to play. “But if I were that poor again and poorer, I’d never turn to communism, which tells a man he can’t belong to himself. If you don’t belong to yourself, you’re better off dead.”

A major clue to Murphy undoubtedly lies in his mother. She was a quiet person of rare inward strength. Her religion was the “golden rule.” Audie gathered his knowledge of her from what she did rather than what she said. Through years of hardship and illness, he never heard her complain. Every night she’d wash Audie’s one pair of overalls, so they’d be clean for school next day. And every day he’d tangle with some kid who yelled “Short-britches!” since the overalls failed to keep pace with his growth.

At fourteen, with his older brothers and sister married, he became head of the household. Between Audie and his mother there had always been a deep unspoken understanding. They were now drawn closer by the problem of existence—just as, in later years, the problem of existence on another level drew him close to his buddies. His mother’s failing health made it necessary to let the farm go. Audie worked in grocery stores and at service stations, earning a high of $14 a week. With this, pieced out by odd jobs his little brothers could snag, they got by.

His mother’s illness was long drawn out and painful. She never discussed it nor showed any fear of death. Her patience under suffering and his own helplessness bit into Audie’s heart. “You want to do something with your hands,” he says, “and you can’t. All I could do was stand by and watch her die.”

He was sixteen when the end came. The younger children were sent to an orphanage. This, too, was a bitter pill, but he had to swallow it. His first act on being discharged from the Army was to buy a house for his older sister, so that the young ones might be released in her care.

In 1942 he yearned to join the paratroopers, because they wore such beautiful boots. Since he weighed only 112 pounds, they turned him down. So did the Marines. Falsifying his age by a year, he finally made it into Company B, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division, and promptly distinguished himself by fainting in close order drill.

He joined as a private and came out a lieutenant, having won all his promotions in the field. He joined for adventure, and came out with a profound sense of responsibility toward his fellowman. His friends think that his friend Lattie Tipton’s death marked a turning point for Audie. Up to then, he’d been awarded the Bronze Star The rest came after Tippy died.

It happened on D-Day m southern France. They’d shot two Germans in a foxhole and jumped into the hole themselves to reconnoiter. Somebody waved a white flag. As they stood up, the enemy machine-guns started. Tippy’s body fell back against Audie and the dead Germans.

War is war. A fake flag of surrender is something else again. It made Audie mad. Icy and purposeful, he climbed out, took shelter where he could, and killed or wounded every German on the hill. For which he later received the Distinguished Service Cross. His job done he returned to the foxhole, pulled Tippy’s body out. removed his personal effects, made a pillow for his head, then sat down beside him and bawled like a baby.

He’s given all his medals away to kids. This indicates no lack of appreciation on his part. He can be just as grateful without owning the medals, and somewhat more comfortable with the memory of those who gave their lives. “How can I flaunt the Distinguished Service Cross?” he once asked. “Tippy did as much as I, and all he got out of it was a wooden cross.”

He came out knowing that he was his brother’s keeper, but he refuses to let that feeling be fancified. Audie’s citations read like a miracle. So do some of his exploits. A publisher, considering his book, “To Hell and Back,” sat agape over the story of Murph sending his men back to prepared positions, while he directed artillery fire alone against six tanks and 250 Germans.

“There must have been some great spiritual awakening here,” said the publisher, “which ought to be stressed.”

“Nothing of the kind,” returned Murphy. “I was just tired of seeing men die. They had wives and kids to go home to. I had nothing. If one man could do the job, why kill thirty?”

He wrote the book partly in response to thousands ot letters, partly out of desperation for something to do. Originally his heart had been set on West Point after the war. This proved physically impossible, since he’d been shot up a little worse than he realized. Then came Jimmy Cagney’s offer of a contract, Audie was inclined to shrug it off at first. However, while glory rained on all sides, jobs hid their heads. Texas folk seemed reluctant to hire Murphy, lest they be accused of cashing in on his publicity. You can’t eat glory. So Audie came to Hollywood. It presented a challenge, and a challenge is something he’s temperamentally unfit to turn down.

“Cagney,” he says, “was always wonderful to me. He simply had nothing for me to do, and you can’t take money for doing nothing. The studios were opposed to using me, probably for the same reason as m Texas. Apart from the fact that I couldn’t act, which they seemed to think important.”

During the drought, he and writer Spec McClure came to be friends. “Why don’t you put some of that stuff on paper,” asked Spec, “and let me see it?” This notion seemed to Murphy an improvement over eyeing four walls. He went to work. Spec helped him arrange and edit the material Without him,” says Audie, “I couldn’t have done it.”

Meantime, through Paul Short’s backing and his own good test, he got “Bad Boy.” Then the Universal contract.

His marriage to Wanda Hendrix shattered on that well-known Hollywood reef—career trouble. Wanda, too, had broken through lean times into glamourland. Her career was important, financially and otherwise. Audie knew and accepted this. Other movie marriages might go to pot. He and Wanda were different. It couldn’t happen to them. But it did happen.

On the surface, their differences may have seemed minor ones. Wanda loves the gaiety of parties, as most girls do. Audie detests parties. The crowds hem him in, the dancing means nothing to him.

The molehills grew into mountains, revealing a basic rift. On one side stood Wanda, clinging to both husband and work. On the other stood Audie, realizing at last that he couldn’t share his wife with her job, realizing too that he had no right to ask her to give it up. But neither could he give up the conviction that a woman belonged first at her husband’s side.

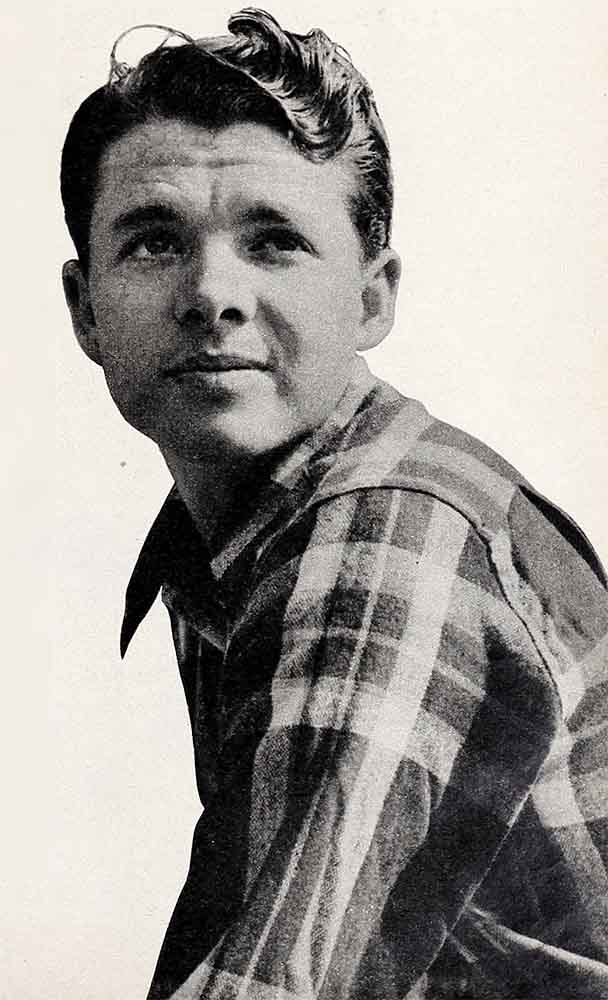

He lives in a pleasant two-room apartment, and looks after it himself except when he’s working. His idea of a good evening is to sit with friends and have dinner and talk. Sometimes he likes to be near them and not talk. The sense of their presence is enough. Sometimes he doesn’t feel like barging in on them. In which case, he stays home with his books and records.

For the past five years he’s been giving himself the education he missed in childhood—an education he must have hungered for. He’s highly articulate, and there’s no trace of the sharecropping farmer in his speech. His manner reflects the poise of inner security In music, his taste runs to symphonies and old operettas—jazz is too jumpy for him.

He appraises humans for what they are. His sights cut through rank, position and wealth, which leaves him unawed. At a Washington dinner he sat beside General Marshall. Someone asked later what he thought of Marshall. “I liked him,” said Audie. “He seemed a very humble, simple, honest man.”

By the same token, he can’t abide a phony, and gives them short shrift. His bluntness can wither or electrify, depending on where you sit. A major, decked out in Pentagon ribbons, expressed a desire to meet Audie Murphy on the set. He went into the tired routine about medals.

“Yeah,” said Murphy.

“I’d like an autographed picture of you, Lieutenant.”

“Let’s cut out the bull,” Audie suggested. “I’m no longer a soldier. If you want a picture of me as an actor, that’s fine.”

He has a great tenderness for children, and the shyest will climb into his lap. “The only innocent things left in life,” he’s been heard to remark, “arc kids and dogs.” His favorite hangout is a filling station run by an ex-cop named Earl McCaskill. One day he was teaching McCaskill’s two-year-old, Roddy, to dance. An agent happened by, and Roddy wound up as the little oatmeal fiend in “Sitting Pretty.”

For animals also, he feels a sense of protectiveness. In his time he’s shot two or three deer, but that time is over. Now he’ll stalk them for hours and, having caught up with them, turn away. “It’s just an excuse for being outdoors. I find there’s nothing like a mountain to cut a man down to size.”

Overseas once they trapped a convoy of horse-drawn artillery and wiped the whole thing out. Some of the horses were wounded and crying, which broke his heart altogether. Men make wars, horses don’t. You can evacuate a wounded soldier. All you can do for a horse is kill him.

He has three of his own—two in Texas, one in California. The Californian is a humorist. Audie found him in Utah, peeking round the corner like a coy dish and skittering away when the man tried to catch him. So he stopped trying, and there stood the clown at his elbow, sampling his ear. Audie paid twice what he was worth in horseflesh. The excess was for laughs.

His friends have to watch their step with him. Admire the shirt on his back, and it’s yours. “Too little for me. My shoulders got broader.” Refuse it, and you’ll find it in the back of your car.

A girl once said of him: “When I first met Audie, he looked so young and helpless, I wanted to mother him. That passed. I never knew a guy who could take such good care of himself.”

Up to a point she was right. He can cope even with loneliness, but he likes no part of it. Rather than eat a solitary meal, he’ll go without food till he finds himself trembling. We’re all lonely to a degree. Murphy’s loneliness is intensified by long and intimate knowledge of pain, by his acceptance of its place in life and by his personal craving for home and children.

“I’m a simple character,” he says, “and I like all the simple things. The family instinct is strong in me. A wife and kids give you more to live for. That’s what I dreamed of all through the war. That’s what I wanted most and still want most.

“The problem lies in me. I’m moody, I’m not easy to get along with, I’m over-critical in little ways. Maybe I demand too much—a girl who’d overlook my faults, because I can’t change—a girl I’d be able to depend on to the last breath. Maybe I don’t have enough to offer in return. I wouldn’t know. All I know is, I can’t settle for less.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1951

Blatter

11 Ağustos 2023Awesome blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.