Elvis Presley Asked Himself!

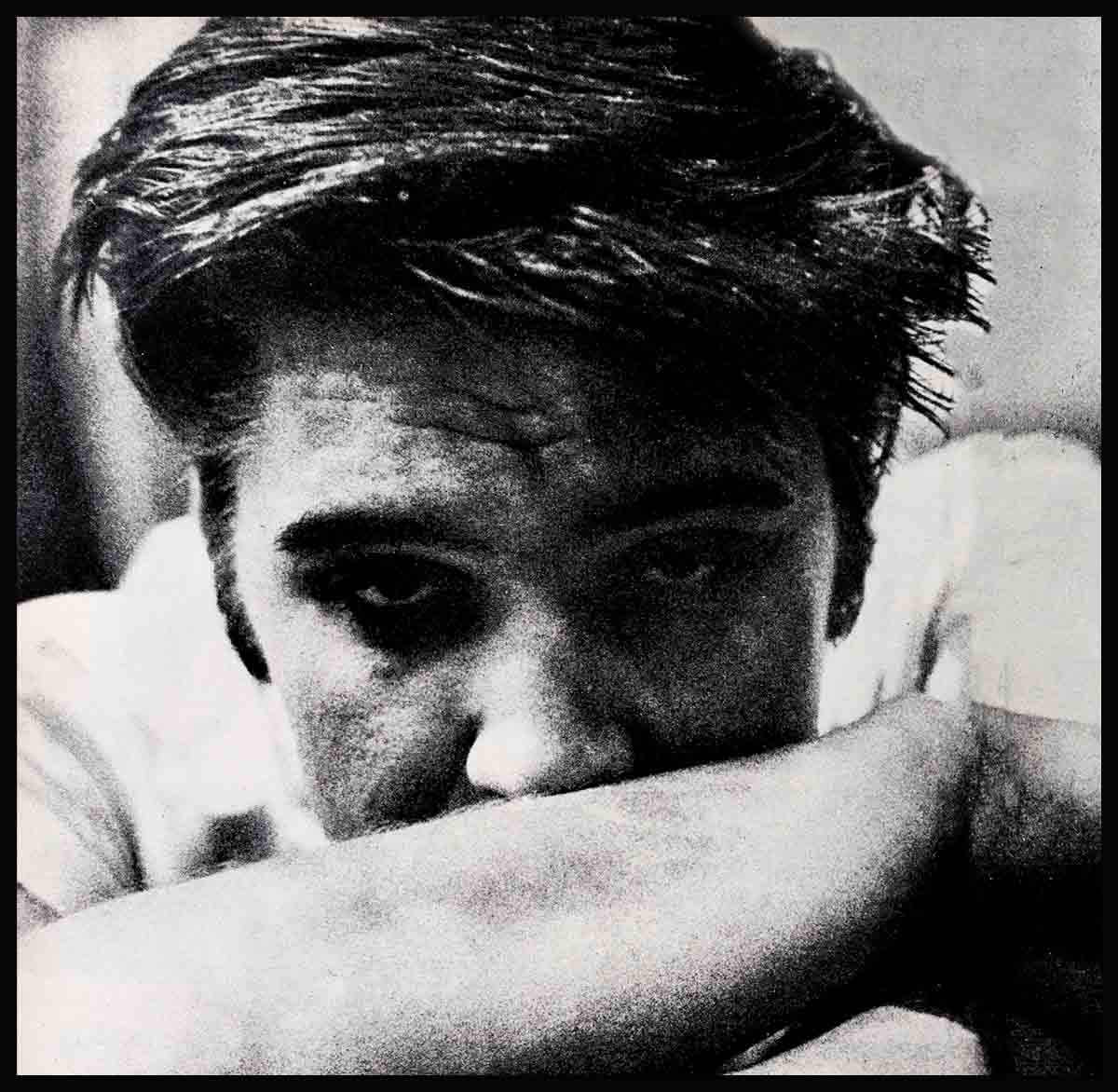

For the thousandth time since that terrible August day when it had happened, Elvis Presley asked himself that question. “Why did Mom have to die now?” He straddled a chair, his arms folded on its wooden back, his head buried in his arms. She was only forty-two, he thought, that’s too young to die. He stared at the plain barracks wall. Outside was Frankfurt, Germany. That had been one of the things they’d planned together—their first trip to Europe.

When the Army had told his platoon they were being sent over, Elvis had rushed for the phone.

“Mom,” he’d shouted. “How’d you like to go to Europe? Yes, the Army’s sending me. Mom, you’d go first-class. Staterooms on a big liner, the best hotels . . .”

“Oh, Elvis,” she’d protested. “You know Dad and I aren’t used to that sort of thing . . .”

They’d planned the trip and he’d even made arrangements to take a little house for her and Dad near the camp. “On leaves, we’ll drive through Europe. We’ll fly to Rome and visit Zurich and . . .” he’d promised. After years of working so hard . . . years when they couldn’t even afford the bus fare for a simple trip from Tupelo to a big city like Memphis . . . after all those bad times, “I want to give you everything,” he told her. Mom had loved life, yet, not once, when she had sacrificed so much of her life to working hard to give him everything she could, not once had he ever heard her complain.

“Never mind,” she’d say, “I know some day, son, you’ll repay me. I know you’ll make good.”

And he had. Being famous and rich meant only one thing: He could give her the things he wanted, to repay her for all those bad years.

Yet he’d had such a little while to give her all the things he’d wanted her to have. “Why did Mom have to die now?” He couldn’t seem to put the question out of his mind, and he couldn’t seem to find the answer to it, either.

He stared out through the barracks window, looking at the German countryside. The hills had been green with life and beauty when he first arrived. “How she would have loved to see that,” he’d thought. Now, the countryside was bare and windswept—somehow it matched the way he felt inside.

He turned from the window. “Things happen so quickly,” he thought. “And yet there’ is so much to remember . . . so much . . .”

It had been a scorching day at Fort Hood, Texas, that day when his mother stepped out of the dusty taxi. She didn’t look a bit tired. Perhaps it was the excitement of spending a week with him at camp that made her look so wonderful. But towards the end of her visit, he was blaming himself for not seeing that it had been too much for her. He’d looked at her anxiously then. “I should have seen it sooner,” he told himself. The last few days at camp, the excitement, the Texas summer, they had left her more tired than he had ever seen her; more tired than the days when he was fourteen and she’d been working at that factory that made curtain rods, just so he could go out for football after school and wouldn’t have to go to work.

“Mom, are you sure you’re feeling okay?” he kept asking her. But she would only answer his question with a soft laugh. When the time came for him to put her on the train for home, he’d had to fight to hide his fear and anxiety—he knew she wasn’t well.

Then the telephone call came from Dad. “El, Mama’s in the hospital.” His father spoke softly and hesitantly. “Dr. Clarke says she’s got hepatitis. He says it doesn’t have to be too serious but . . . well, I thought maybe you’d like to be here.”

His commanding officer gave him a week’s emergency leave immediately. “Not because of who I am,” he thought. “Any guy would get leave if his mother was sick. And I guess he could see that I’d go to pieces if I couldn’t get on the first train for home.”

The train trip was a nightmare. He sat there, hour after hour, leaning forward almost as if that might make the train go faster. They had to get him a private compartment so he would not be mobbed at every stop. No one knew why he was going home, he told no one but his C.O. and to the guys in the barracks he said his mother was seriously ill. No one knew what he was going through.

It wasn’t until he saw his mother at the hospital that his anxiety left him. He opened the door to her room and saw her. He stood there—just looking. She saw him and cried out, “My son, my son,” and he ran to her side. “I’ll never leave you, Mom,” he said, “never.”

How much better she had looked, sitting up in bed for the first time the next day. Dad had teased her about pretending she was sick, “when all you really want is a little rest and attention,” he had said. And he had joined in the teasing when he realized how much their joking and his stories about camp made her laugh. He stood there holding her hand and smiling but he didn’t feel like it. He knew she was sick: “Acute hepatitis is no fun, El,” the family doctor had said. “Gladys seems to be much better today but she’s still very sick.”

And to the reporters who descended upon him and Dad, he had to admit: “Mom’s not doing too well right now . . . not well at all.”

He and Dad spent almost all the next day with her. She would look at them and say, “I don’t know what I’m doing in here. I feel so much better.” And then, with a smile for both of them, “Maybe it’s just having my two favorite menfolk here that’s cheering me up so.”

That day was a quiet one. When he left the hospital, the reporters that approached him were kinder, a little more gentle in their questions, as if, at last, they realized that he was going through a pretty bad time. “My family is all I’ve got in the world.” he told them quietly, half thinking aloud. “I love them and I like them and I always want to have them around. They can’t be replaced.” Elvis knew Mom felt the same way. His twin brother had died at birth.

“Can’t I spend the night at the hospital,” he had asked. But there was no room and his father insisted he go home to get a few hours of sleep.

The thought that he should not have left his mother that night will never be erased. “If only I’d stayed, maybe things would have been different, if only I had been there,” he thought. Instead, there had been the ringing of the telephone. He wasn’t fully awake when he went to pick up the receiver, but he knew . . . he knew something had happened at the hospital. He didn’t want to answer it, but he did, picking up the receiver very slowly.

“Elvis? . . . El? That you?”

“Dad? What’s wrong?”

“It’s over, El.”

His mother had passed away in her sleep. She died of a heart attack.

Visitors to the funeral home the day of the burial filled up more than thirty guest books—ninety names to the book. Reverend Hamill, pastor of the First Assembly of God Church, stood up. His voice was clear and strong and Elvis remembered that he, too, had called her “a young mother.”

“A eulogy to Mrs. Presley would be unnecessary,” he said, “for the whole nation knows she was a lady of extreme modesty and simple tastes. She certainly would not want it.

“I would like to recall, instead, how devoted she was to her husband and son. The whole world has taken notice of this. The strength of her character is revealed in the influence she has had on her famous son.” He continued to speak in reminiscent tones, recalling the “lean days” of the early years of the Presley family, just as Elvis had done at the hospital when we had visited his mother. “We didn’t have nothin’ before—nothin’ but a hard way to go,” he’d said to her. These things Reverend Hamill spoke of and then he said, “When fame and fortune came, it did not change Mrs. Presley’s perspective of life.” He turned and spoke directly to Elvis: “You can take great comfort that thousands upon thousands around the world are praying for your spiritual guidance through this dark hour.” He turned from Elvis and closed the burial service with a benediction. He’d struggled from his seat, limp and torn with emotion, and walked slowly to his mother’s bier.

“Goodby, darling, Goodby darling!” he cried out. He moved closer. “I love you so much. I love you, darling. You know how much I love you. I lived my whole life for you. We’ll keep the house, darling. Everything that you loved. We won’t move a thing. Goodby, darling. Goodby, baby. I love you . . . I love you . . .”

His voice trailed off as funeral attendants gently led him to a waiting limousine.

He sat in the large funeral car, slumped down with grief. Everything was hushed and still and he could hear the voice of an elderly lady behind the roped-off section, saying softly, “The poor boy. Not all boys loved their mothers like he did. Why did she have to be taken from him?”

And when Elvis returned to Graceland, he sat out on the porch steps, and he thought the same question . . . “Why did I have to lose her? Why?” And he looked around the grounds of Graceland and felt the warm sun on him. He heard the birds off in the chestnut trees and thought of his mom. She always loved a day like this. He thought of the houses he’d bought for his parents and then he thought of the day he’d bought Graceland for them. “Oh, Elvis,” Mother had said when she saw it for the first time. “It’s so big, Elvis, so grand . . .”

Fleeting moments of his life with his mother and father rushed across his mind. He thought of Mrs. Foote, their Memphis neighbor who was so good to them when they were poor. He remembered what Mrs. Foote had said about his Mama. “El, I just want you to know I don’t think fame’s ever gone to your head nor your Mama’s either. Gladys knew that sometimes I just get tired livin’ cooped up here. She called me one day and asked me to dinner at Graceland and for some doings afterward. And she said, knowing how excited I was, ‘I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll bring you out in the pink Cadillac, and bring you back in the yellow one.’ Your Mama’s a wonderful woman, El.”

But nobody had to tell him that. She’d always been there when he needed her. When he’d fall down and skin his knee, or when he’d have a fight with one of the other kids, she’d always be such a comfort. And she would always see that he had toys and clothes like the other kids, even when it had meant she’d have to work long long hours as a nurses’ aid, and for just twenty-eight dollars a week. No, when the time came for growing up, it was never his folks hg wanted to rebel against, but the poverty that kept them working so hard. . . . And yet, it was poverty that kept them so close to one another. “I’ll be someone someday,” he had promised her.

How strange, he thought, that it was Mama who guided him, unknowingly in a way, along the right path . . . “Why, Mrs. Presley, your Elvis has a fine, strong voice.” That’s what folks at church in Tupelo used to say when he’d sing at services. But it hadn’t been performing exactly; it was just having fun. He’d sung hymns and things with his Mom and Dad as far back as he could remember. They enjoyed singing together—they enjoyed everything they did together.

And it was Mom who was responsible for one of the biggest turning points in his life. He was eleven that summer the cyclone came. She had hustled him into the cyclone cellar, a covered excavation, near their house.

They sat there singing together for a while, because Gladys knew he was scared and she’d always said singing was good for the spirits. Then they got to talking and he had asked her about the bicycle he’d been admiring in the general-store window.

He remembered how she looked at him, her eyes so big—and so sad. “Now look, honey,” she said softly, taking his hand in hers, “it costs fifty-five dollars, and that’s a lot of money for us, especially since your Daddy’s been sick. Besides, we’d feel a lot safer if you’d wait till next year for a two-wheeler.”

Even though he really understood, he felt awfully let down. But then she said, “I’ll make a bargain with you. If you’ll wait a year for the bike, your Daddy and I will get you that guitar in the window next to the bike. How would that be?” He wasn’t so sure. He never even thought of learning to play a guitar. “It would help with your singing,” she went on, “and everyone does enjoy hearing you sing, honey.”

Dad had been right when he told someone, “Gladys and I saw to it that Elvis never wanted for anything, even when we were troubled.” And then, as he looked out over the spacious lawns of Graceland that Gladys had loved so well, he remembered thinking of what he had said to her when he was nineteen and his first hit song, “That’s All Right,” was breaking records. “You’ve taken care of me for nineteen years, now it’s my turn.”

Tears welled up in his eyes as he stood by his barrack window, thousands of miles from his home—from his mother’s grave . . . “How,” he asked himself “how could you repay people for loving you so much, doing so much for you?”

And then, as he looked across the gray dawn of the German countryside, the answer came to Elvis. It was as though some higher power had felt and heard his grief, seen his unhappiness, known his pain. For suddenly, Elvis understood a little. The new house, the cars, the trips, the parties—these were only tokens of love. Love couldn’t be repaid, except with love. And Elvis knew in his heart that he had given his mother love. And he was comforted.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958