Van Johnson: “My Life”

PART II

Ilanded in New York in a bitter rain with five dollars in cash and my mother’s address in my pocket. My mother had remarried and lived, I soon discovered, a long way by subway from Broadway, out in the Sheepshead Bay district.

Mother hadn’t seen me for sixteen years, since I was three, when she and Dad were divorced. She was wonderful to me. She and my stepfather gave me a room, lunch money and encouragement. I assured them I’d soon repay them, since I would be making big dough almost immediately. I didn’t mention my name in lights, but privately that idea glittered at me. I wrote Lois frequently, implying, even saying, that when Johnson hove into sight in these agencies, they greeted him with open arms.

AUDIO BOOK

Lois wrote back the ideal kind of only-girl letters which, boiled down, said one thing: Dear, you’re right. Not that that was a surprise. After all, she was the one whose faith had spurred me on to abandoning the home waters of Newport and trying my luck on Broadway.

Did I say luck? My optimism again.

I went into the Broadway agencies and not an arm moved. Not an eyelash batted. I was strictly Mr. Nobody from Nowhere and I could keep on being same, till death did us part, for all of Broadway.

It wasn’t that I didn’t try. I did all the things. I tramped miles. I called in daily. I smiled. I hoofed. I sang. I did everything but take out my ribs, one by one, to attract attention.

As the weeks went by, I began being sick with guilt over taking that lunch money from my mother. Inevitably I discovered that spot all aspiring Broadway kids discover, the Penn-Astor basement lunch counter, where a big meal costs twenty-two cents and no tips accepted, but even that daily twenty-two cents plus a dime carfare was getting me down.

Yet that first year I did get in one show, a dilly called “Entre Nous,” which was so darned entre nous that it practically remained a secret from the public. Of course its being hidden away in Greenwich Village helped the public to avoid it. We played The Cherry Lane Theater, but there wasn’t any cherry tree, and no lane and the theater itself was so small that such audiences as we had practically sat on the stage among the acts. But at least and at last I was a professional. I sang and danced. The show ran four weeks and we got paid one. My wage: $15.

Nobody discovered me.

The second year things began to break. Because I answered a chorus call wearing tap-dancing shoes, the harassed dance director decided I must be old Johnny Fleetfoot and hired me without so much as a tryout. By the time we got into rehearsals, I’d picked up enough steps to get by. Saved for my art by a metal tip! The show was called “New Faces.” It ran a beautiful forty weeks with me getting forty bucks for each and every one of them.

I was able to repay my mother and move into a room on 46th Street right near Times Square, in the midst of the bright lights, in the heart of the theater world. Technically, the room was furnished—but it is more accurate to say it was filled—with a bed, a chair, a bureau, a washbowl. It had no clothes closet but I needed none. After all, when you have only one suit you have it on except when sleeping.

When “New Faces” closed, did I worry? Certainly not. I was all set to go ahead now. So I went backward. The only job I could get was in the chorus of the Roxy, a movie house, at $30 a week, but a chance to see all the movies, which I did. I was and still am a rabid movie fan. Right now I’m making a collection of old movie magazines. I dote on them.

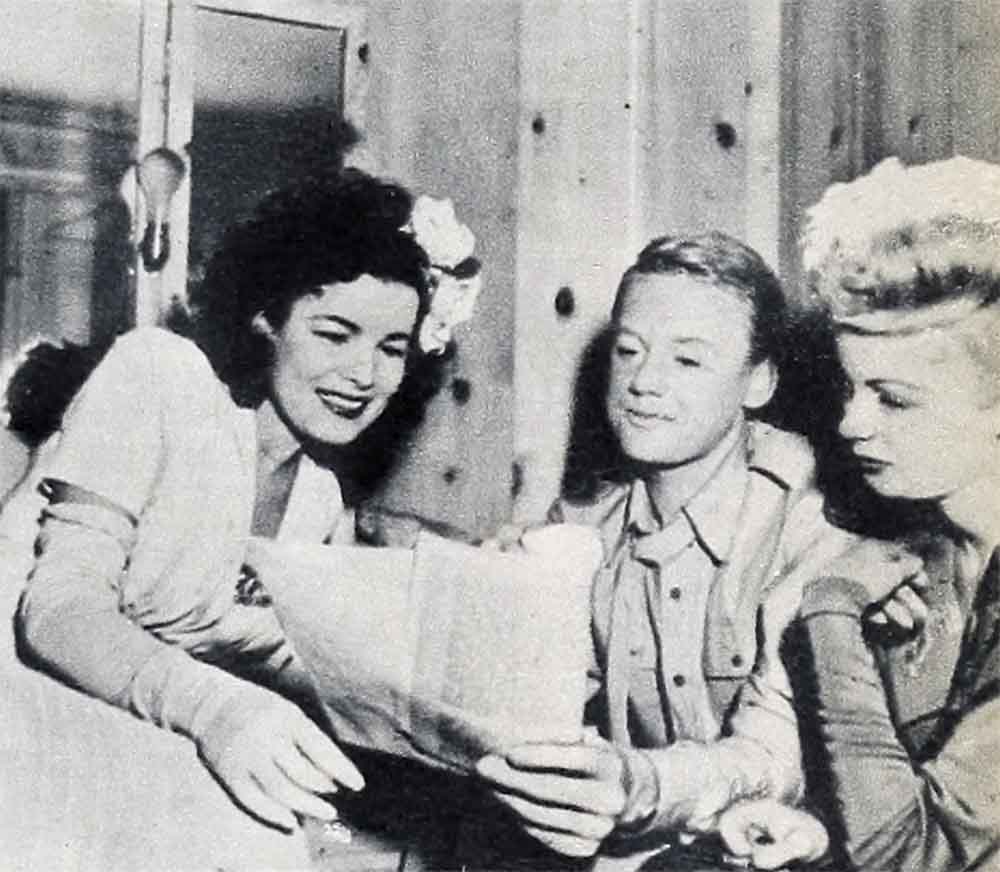

But at the Roxy, I really did get discovered. A swell girl, Lucille Page, wife of Buster West, the comedian, came backstage one day and asked me if I’d like to work in a vaudeville act with her and Buster for $75 a week and all expenses. Would I? Do mares like oats? Do little lambs like ivy? We went out on the road and traveled till Lucille decided to take time off for motherhood. Now I know how a producer feels when some starlet tells him those same tidings.

Back on Broadway—this time with an oufit called “Eight Young Men Of Manhattan.”’ Tricked out in white ties and tail coats we formed a background for Mary Martin, queen of Broadway that winter because of her heart belonging to Daddy. We did our act on the Waldorf’s Starlight Roof. The atmosphere did something to me. Surrounded by that elegance, I felt I could conquer anything. I decided to go back home and see Lois. Just as I was trying to get the time off to do this, I got her letter. Lois was going to be a bride, all right, but the cast had been changed. There was another guy whom she was marrying.

Sometimes I wonder if it is because we Swedes come from such a frozen country that we ourselves thaw out so seldom, or reversely, when we get set into a pattern or emotion we freeze to it so solidly.

To call it heartbreak I went through is dramatizing it too much. I faced the truth that Lois was right. We still wanted the same things: A home, security, lots of kids. But as my wife what chance would she have at them, with me making $50 one week, nothing a month later and $30a week ten weeks afterward?

I got me another girl. She wasn’t a bit like Lois. She was actually much more beautiful, much more vivacious. She had sparkling eyes and a drape shape of the first water. She was a Broadway starlet. She loved to sing and to dance and she was a wonderful companion. I told myself I was in love. What we had in common was Broadway. The only trouble was that I was beginning to be sick of Broadway.

The Broadway of success is a swoony proposition but the Broadway of slow openings and quick closings, of going the agency rounds, of trying out, of flash money one month and careful hoarding the next—well, here comes the Swede in me again. I couldn’t see it as getting anywhere. It wasn’t my way of life. I kept trying out for speaking parts and ending up in the chorus. George Abbott gave me a chance at a speaking role in “Too Many Girls,” groaned as he listened to me, stuck me in the chorus, yet strangely enough, when he came to Hollywood to do the show on the screen, once more gave me a chance at an acting spot.

I kissed my girl and Broadway good-by and headed for RKO. They gave me a test and a return ticket. I went back to everything but the girl. The Abbott office actually gave me lines to say in “Pal Joey” in which the leads were June Havoc and Gene Kelly.

There is nothing so rare as a girl like June. It was excitement at first sight for us. Gene was courting Betsy Blair, who is now Mrs. Kelly, and we four went everywhere together. I was in the chips, $150 a week. I had six suits. Life was strictly on the beam—too good to last. Hollywood paged June. She left. Hollywood paged Gene. He and Betsy left. Then, finally, it paged me.

This was more like it. I’d be seeing June and seeing Gene, matching my contract with theirs. I made one slight miscalculation in those dreams, the fact that I came back practically by return plane.

Yes, I made another test, at Columbia this time, opposite Janet Blair, who is a nice girl to be opposite, even if the Columbia officials didn’t feel the same about me when they viewed me. On Broadway I went back into “Pal Joey,” which promptly closed, perhaps from shock.

Mr. Van Johnson hit an all-time low. He took himself to Newport, ate clams, looked out to sea and asked himself what it was all about. Mr. Johnson knew a lot of questions and no answers whatsoever.

Then the telephone rang. Good old telephone. An agency was on the wire asking if I’d consider a six-months’ contract with Warner Brothers, starting immediately. It was like asking a drowning man if he would consider being rescued by a yacht.

I went out in style, a lower berth. Johnson, the contract actor. Six months in which to make overwhelmingly good. I practiced expressions all the way. I wondered what gracious words I should say to the group that would meet me.

Nobody met me. I called Warner Brothers and told them I had arrived in glamorous Hollywood, that I was, in fact, registered at the glamorous Beverly Hills Hotel. They said all right. I called my agents and gave them the same glad tidings. They said all right, too.

But next morning my eyes were shining and girls were singing and Warner Brothers were on the wire. Said they: “Your six-months’ contract entitles us to give you a six-weeks’ layoff. We are putting you on layoff starting today.” In less fancy language that meant I was off-salary. Ah, the warm welcome of Hollywood! Ah, the wonderful hospitality! Ah, nuts!

Still, there was June Havoc, bless her, and the six weeks went by. I couldn’t see much of June because she was working practically day and night. I couldn’t see much of Gene because of the same setup. But being a sun worshipper, I didn’t suffer and at the end of the six weeks the checks began coming.

I called up Warners to see if I couldn’t do a little work for these checks. Day after day, nobody was in. June said I ought to go to Warners and show myself. “Lunch in the Green Room,” said she. So I went to the Green Room and snagged a table close to the wall. I gazed pop-eyed at everyone, really big stars, really big directors, but no one saw me. I was the invisible man to everyone except one waitress. She came over and said, “You’re not allowed in here. This is only for stars and directors.” I can take a hint. I got out and stayed out.

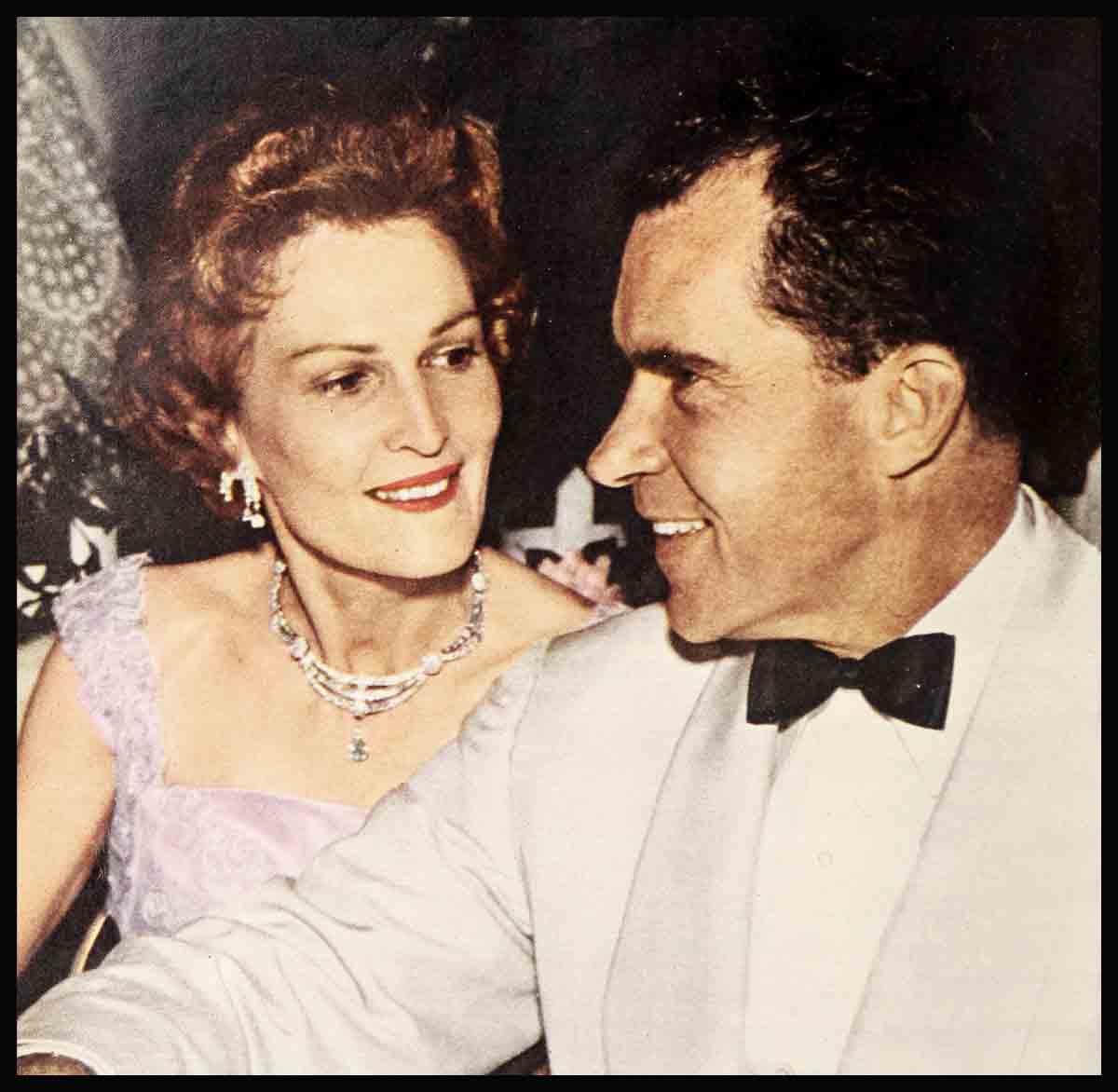

At the end of five months, I got my second call from Warners. They said they weren’t taking up my option. This did not surprise me. Having hired me sight unseen there was no rule why they couldn’t fire me similarly. I thought nothing they could do would surprise me, but two weeks later they bowled me over by calling a third time and this time saying I was to play the lead in “Murder In The Big House.” The leading lady was super-swell Faye Emerson. The picture was shot in twelve days, just time enough to get me in under the end of my contract. I walked out of frames, waved my arms and in general couldn’t have been any worse.

My final night in town Desi Arnaz and his wife, Lucille Ball, called me up and took me to dinner at Chasen’s. Until that moment, I didn’t care at all about leaving Hollywood. I knew no one but June and Gene, who still, through no fault of their own, hadn’t time enough to see me.

But there was something in Chasen’s atmosphere that was warm and friendly. I saw nice people around and I was introduced to some of them. Gary Cooper, for instance, who really looked at me, really greeted me. Suddenly, sitting there at the bar, I wanted to put my head down and wail with misery. I wanted to stay and be a success.

Billy Grady walked up.

He was an old friend of Lucille’s, whom I had met once in New York. He asked me what I was doing. I told him—he told me to come to M-G-M the next morning.

At M-G-M, people were actually kind to me. I might be a nobody but at least I was human. I got make-up tests, voice tests, coaching, was taught camera angles. They told me blond men weren’t star material. I’d have to dye my hair. At that moment I’d have dyed my face if they had said so.

Actually they didn’t dye my carrot locks. They just sprayed them, from a spray gun like the ones housewives use to frighten gnats. I felt smaller than one when I saw myself. On me black hair didn’t look good, I thought, but I wasn’t setting myself up in judgment against. those nice M-G-M-ers.

Right away they put me in a “Crime Doesn’t Pay” short. Each morning I’d report to make-up and they’d spray me into a brunette and each night I’d wash me back into being a redhead again. all went well until we had to work in a rainstorm. My hair ran all over my face or rather its color did. They nearly cast me in a Tarzan picture, I made such a snazzy zebra.

Nevertheless, I got my first chance at an A picture after that—“Cairo” with Jeanette MacDonald. They made me up, not only with my spray-gun hair, but with a mustache and a pipe between the teeth. I had a bad moment when I was called to do a test with a girl who had once been a star. Back in Newport I had drooled over her beauty but now I saw what bad health and bad luck can do to a girl like that. Neither of us got the roles, but I got a good lesson. I had learned, by shock, that a career must be guarded every minute.

Then the front office called me and told me I was going into “Somewhere I’ll Find You” with Clark Gable and Lana Turner!

There was a war scene with thirty men in a trench, all dead but me. I was to crawl through them, while shot and shell burst over my head and as I poked my way up around their shoulders and arms I was to utter bright lines. I blew my lines and the director blew his top. I wished I were really a dead man. I did the scene again and again, with him getting madder and madder. About the fourth time as I crawled through, one of the corpses began tickling me. I laughed in spite of myself, and relaxed. I looked into some slap-happy eyes and recognized Keenan Wynn, whom I knew slightly. Because I was relaxed, I went through the scene without a break and right there began a sincere and lasting friendship.

That was my only scene in “Somewhere I’ll Find You” and I never even glimpsed Turner or Gable.

But the tide had turned. Came “The War Against Mrs. Hadley,” “Pilot No. 5,” my first Dr. Gillespie picture followed by a second, and finally “A Guy Named Joe.” I had friends, very close friends like Keenan and his wife, Evie, and wonderful helpful friends on the lot like Fay Bainter in “Mrs. Hadley” and Lionel Barrymore in the Gillespies and finally that wonder woman, Irene Dunne.

I felt she didn’t want me for that part in “Joe.” I knew nobody wanted me really. After all, who was Van Johnson? They . had already tested so many guys so much more important than I and when Vic Fleming, the director, introduced me to Irene, I knew just how interested he was when he said, “Miss Dunne, this is Mr. Van Warren.” Didn’t even have my name straight!

I had to test on a love scene. I stood there, my face against the beautiful face of a star miles above me. So what did she do, that feminine miracle? She pretended she was nervous! She made believe she didn’t remember her lines. She made up lines when I faltered. Five minutes later making love to her was no strain. The strain was in not making it too real!

Well, I got the part and then came my automobile accident. It’s been told so often I won’t go into it here beyond saying that I got sideswiped when I was on the way to the studio with Keenan and Evie. I went down and out and came to, with my face all scarred, a possible brain injury and a definite 4F status.

All I thought of at first was, this gives Dunne the out. She doesn’t really want me in that part and now she can get rid of me. Instead, she fought for me and they held up the production till I got well.

People tell me that accident changed me. But I think it only intensified the kind of guy I am. Until then I’d been a little shy about admitting how much I like to stay home alone, reading, listening to records, mapping out the years ahead. Now I’m not.

The studio’s given me wonderful parts such as the sailor in “Two Girls And A Sailor,” followed by Ted Lawson in “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” and the fan mail says I’m across. I’ll confess, it’s terrific.

In fact, I’ll let you in on a secret. I’ve worked steadily, almost without a day’s rest, for two years now, so recently I took a vacation in Mexico. Nobody down there knew me and at first it seemed very sharp, walking through those little towns. I really went for it—for about one day. Then I began to get lonesome for people nudging each other as I passed, or smiling at me, or saying, “Would you sign this?” When I came back and the crowd in the airport recognized me, I got a great kick out of it.

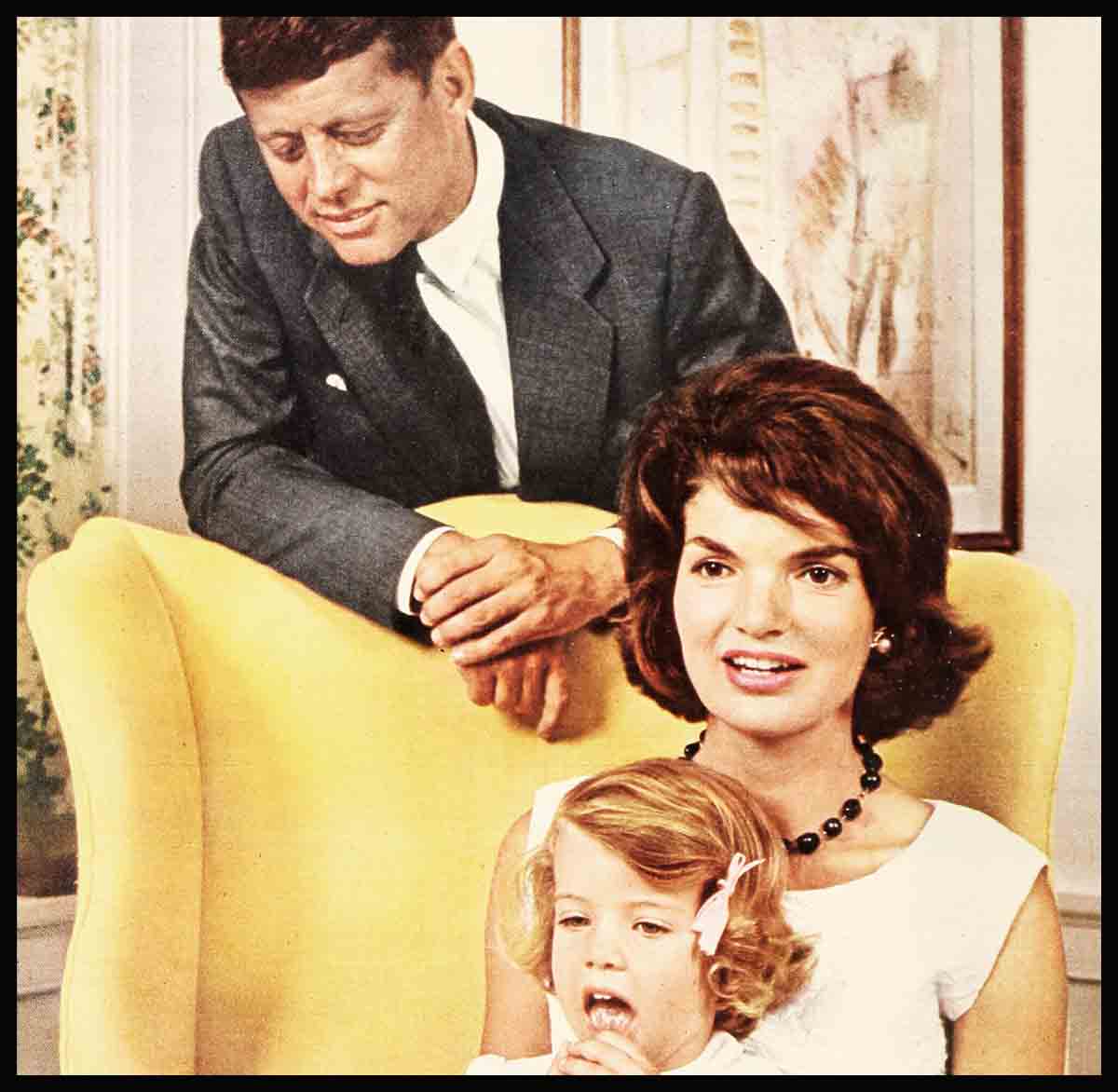

The future? Comedy parts, I hope, mixed with a little drama, and me learning to be a better actor. And that girl I’m looking for. Whether she’s a blonde or brunette, I do not care. Whether she’s an actress or a home girl or a white-collar worker matters not at all to me. When she comes along, I shall know her.

Then I’ll marry and I’ll hope to have not one or two children but five at least, and a home that will be as much like New England as anything in the West can be. And the things I’ll want in that home will be New England things that I will share with my wife and children, the qualities of independence, free thinking and free speech, hard work and friendliness.

That’s my dream, but even if I don’t get it, even if I don’t attain half of it, I know I’m still way ahead, and a very lucky guy, and I’m grateful.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1945

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments