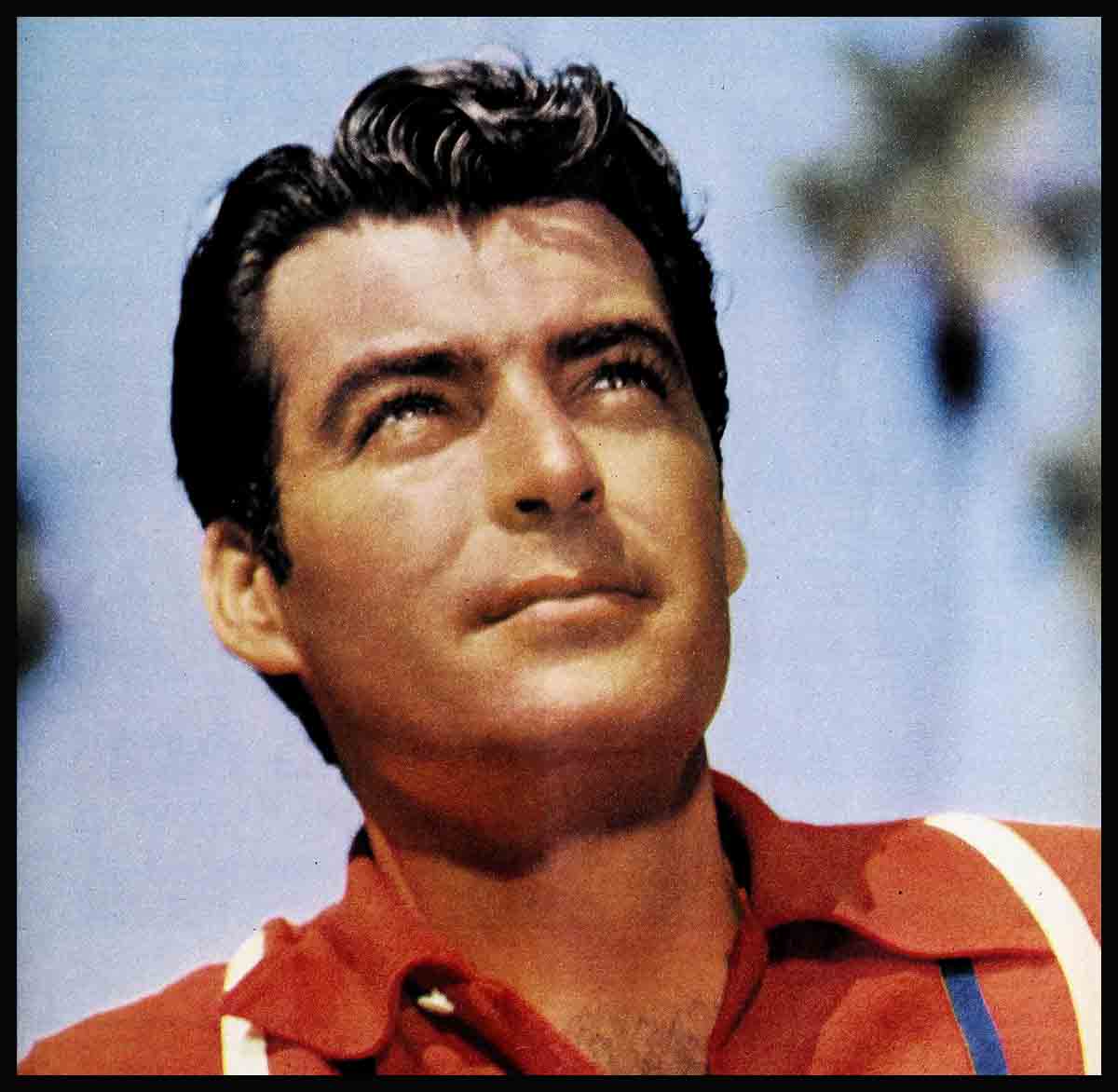

Keeping A Date With Love—Rory Calhoun

His dark blue suit is five years older than when he wore it on that special day. Moths have taken possession, and it’s ten pounds too large. Her once crisp, gray chantilly lace has gone a little tired. And it’s perfumed with the unmistakable aroma of having been packed away too long.

But come August 29, Rory and Lita Calhoun will be slipping sentimentally into those same old garments to keep a standing date with love.

“Marry me forever—and five years,” Rory had said when they were planning their lives together. “Five years from our wedding day, let’s be married again, God willing. The vows we take then will mean even more to us than our first ones, for we’ll be even closer and time will have proved how much we belong to each other.” And maybe by then, he said, a character called “Smoky” Calhoun might actually have come to believe that he has a right to that much happiness.

They were very much in love, these two, when they stood at the altar in the Trinity Episcopal Church in Santa Barbara that sunny summer day. “We had nothing but each other and a thousand dollars I’d saved and a mortgage on my car,” says Rory now. Even the new blue suit wasn’t his outright. He’d got it on long-term credit from a tailor who was willing to take a gamble on Rory’s future in films.

And so, with the mission bells ringing in the background, they were married—for richer or for poorer—forever and five years.

They had no way of knowing how much “richer” they would be when their five-year anniversary rolled around. There was no hint that Rory would be under contract to Twentieth and one of the fastest-rising stars in Hollywood. And they couldn’t have guessed that, when next they were married, Rory would be on location thousands of miles from home in Alberta, Canada, co-starring in a CinemaScope epic called “River of No Return.” Nor that Bob Mitchum would be best man and Marilyn Monroe, maid of honor.

But what Rory did know, and believed devoutly from the beginning, was that theirs would be a relationship that would grow dearer, mature happily along with the gray lace and the navy blue suit. Although he couldn’t know then how much dearer, how many experiences, both heartbreaking and hilarious, tempestuous and tender, would be shared.

The comfort of the words, “I, Lita, take thee, Rory,” was brought home to him almost immediately after their marriage, when Rory had to go on location in the Navajo country in Arizona. Never had he known such loneliness. And as a guy who’d lived with the trees, the rivers, the sun and the sky, never had he thought he could. “We’d just been married a week. I went crazy. To have so much happiness, then to be separated—it really leaves you with nothing.”

He wanted to tell Lita how he felt. And he tried every night. But in this remote country, he was on a thirty-five party line and the natives just couldn’t resist listening in on what the “picture folks” were saying. Every time he raised his receiver, one by one they raised theirs until the connection was weakened to a whisper.

“I can’t hear you,” Lita would keep saying.

“What did you say, darling?”

“I can’t hear you”

“What did you say, darling?”

“She said she couldn’t hear you,” one of the party-liners interpreted. As more receivers clicked up, Rory and Lita screamed themselves into faintness, until finally the thirty-fifth blacked them out completely. What he felt would wait. It would have to. . . .

“Until death do us part,” they promised. And those words were never closer and never to be remembered more than during Christmas in Korea together on Bunker Hill, with the heavy boom-boom of the 155-Howitzers drowning out the sound of “Silent Night” and an over-conscientious Korean guard keeping them a kiss apart.

Their unit, with Rory emceeing, had been giving shows all that day. Going back to the tent for chow, remembering the happy faces of GI’s watching her sing and dance, Lita had never seemed dearer, thought Rory, than that moment—in fatigues and with a smudge of dirt on her cheek. After the party, they went to their separate quarters. But Rory wanted to kiss her goodnight—again—and tell her just how much she meant to him—again. He was stopped at the door of the women’s quarters by a Korean guard, rifle in hand.

“No-no-no . . . no men,” was all the English he could say, but he kept saying it over and over very effectively.

“But she’s my wife,” Rory kept saying.

“No-no-no . . . no men,” the guard replied.

“Show him your ring, honey,” Rory urged Lita, who was standing on the other side of the gun. “Look—ring—married—husband—wife.”

The guard examined the ring interestedly. Then, in turn, showed them a ring he was wearing.

Encouraged, Rory moved in—to cold steel. “No-no-no! No men!” And saying, “See you on the helicopter, Honey,” Lita stepped back into the tent hastily, rather than risk a kiss of fire.

But being separated by a rifle is as nothing compared with being 7,800 miles apart, as they were one memorable New Year’s Eve.

“Forsaking all others.” These words they’ve remembered, but gossip columns seemed to forget them, they found during that terribly lonely time when their careers kept them apart for three months. From time to time, one columnist in particular raised the rhetorical question, “A trial separation for the Calhouns?”

Theirs was a trying separation, but not in the way she meant. They’d spent every New Year’s Eve at the Ojai Inn, where they’d honeymooned; but this year Lita was headlining the act at Ciro’s with Billy Daniel, and Rory was in South America making “Way Of a Gaucho.” Some way, he was determined to get back to Hollywood before her engagement ended January 3, and applaud her from out front. When the company finally finished the film, the Bowl games were on and there wasn’t a plane reservation to be had. “Just give me an open ticket. I’ll take the chance,” he said.

Rory hitch-hiked through the air—7,800 miles of it—so slowly he felt he was barely inching his way across the sky one cloud at a time. He sweated it out waiting for the next available space in Tampa, Birmingham, and New Orleans. He landed at Los Angeles at 11:30 p.m. And rushed straight to Ciro’s, tired, dirty, and with a three-day growth of beard, just in time for the last half of Lita’s last show. He was close enough to touch a whirling ankle as she danced, but blinded by the lights, she didn’t see him. She was leaving the stage when Billy Daniel whispered, “Nice Rory got back.” He saw the curtains part again, heard a happy cry, and Lita was in his arms.

His first day back at the studio, Rory saw the columnist who’d speculated, “A trial separation for the Calhouns?” In a voice loud enough for the whole commissary to hear he shouted, “No, we’re not getting a divorce!”

The mere word “divorce” grates against the grain of a guy whose wedding vows grow more sacred through the years, and who proves he means it when he says, “I got married to stay married,” by marrying again after five years.

“With all my worldly goods I thee endow” means more now too. And it’s a kick for Smoky Calhoun, homeward bound from Twentieth Century-Fox, to pass by the brick-yard where once he fired bricks, to swing around the service station where he once gassed and lubed cars, anti to turn up the palm-lined drive in Beverly Hills to his first Hollywood home—a New England-style house complete with swimming pool and four bathrooms. “I find that right interesting,” he grins. Once home, he dons jeans and puts as much love and labor into his house as any pioneering homesteader.

In a well-butlered neighborhood, the Calhouns are a busy pair. “It isn’t that we can’t afford help exactly, and we do have somebody in once a week to help wash woodwork and windows and scrub, but the way we see it, when you do things around the place yourself, you take more interest in your home.”

It was Lita who found their house, with its roomy backyard, the tall, tall trees backgrounding the property, and the swimming pool and dressing room that were once a part of the old Will Rogers estate. The trees keep shedding into the pool, but as Rory says, “The only way to get rid of that is to get rid of the trees—and that doesn’t make sense.”

They’re Early Americanizing the whole place, refurnishing and decorating it in vital dark greens and rich, red-brown paneling. After Rory finished “Powder River” he built a knotty-pine breakfast nook in the kitchen and papered it with Robert E. Lee patterned wallpaper. He converted the maid’s room into a den and paneled that. He plans to build a “Western room” over the garage as his own sacred domain, to house his saddles, guns, arrows and eighty-pound draw bows. The piano in the living room will be “old-fashioned” in antique red and gold leaf. Already, they can hear friends of theirs like Debbie Reynolds coming in with, “Dig that crazy Valentine!”

At present they’re refinishing the hall, following Rory’s attempt to get his beloved super king-sized bed up the stairs. This was a colossal fiasco which might have been avoided had he not underestimated his gal’s canny and intuitive eye. His five years have taught him how dependable that eye is. Rory had fallen in love with the bed for their first apartment and wanted to buy it. “But Rory, it won’t fit in,” Lita cautioned. “I’ll take it over the roof,” he said. And after a great deal of struggling he did take it over the roof and through the fire escape, ripping off most of the bottom en route.

Nor would the bed go up the stairs of their new home. But Rory wasn’t to be denied. He kept eyeing the bed, which jammed the whole downstairs hall. “I’ve got it, Iz,” he said finally, using his nickname for her real name, Isabelita. “Well . . . Rory?” He proceeded, without batting an eye, to saw the frame widthwise completely in two. Then the studio called him for a picture, and he left it there, two wounded halves. Lita called in a carpenter, and phoned Rory on the set of “How to Marry a Millionaire.” “There’s a man here who says he’ll fix the bed. For sixty-seven dollars he’ll hinge it back together again,” she said. And heard her husband sigh happily, “I knew there was some way of getting that bed up there.”

For two who came from such different worlds, they’ve weathered their first five years very happily. “Lita’s made more adjustments than I have—to be fair,” Rory says readily. “She was a little hothouse flower when we married. Now she’s camping out like a veteran and loving it.”

Rory himself, he admits now, was a little worried at first as to how she would manage the rugged fishing trips on the Colorado River. But after the first, Howard Hill, famed archer and fisherman who accompanied them, said, “Stop worrying about your little ‘Squaw’, Rory. The kid’s a real natural. She’s used to moving in rhythm. She’ll outrun trouble any time.” And she has.

But the trips have given her some strange thrills. She awakened with a shock one afternoon when she was napping on her cot to find twelve buzzards hovering five feet over her head. “Rory!” she yelled, “they must think I’m—dead!”

But as she says, “Rory will go to night clubs with me too now.” Which, as anybody who knows Smoky Calhoun can tell you, is more than a mild concession. He likes to catch the acts and various bands, but as for “sitting hunched up, with your knees jammed against a table,” says he, “dodging other couples on the dance floor, and just staring across at others who are staring back across at you” he’d rather have a few friends in at home. It’s cheaper and less painful. Furthermore, it seems rumors have a way of sprouting among the night club set. “Just stay out of the traffic, and you’re all right,” he says.

But for an admittedly old-fashioned guy he has no objections to Lita’s having a career. “Why should I?” he asks. “Lita was in showbusiness long before I was—ever since she was a kid. I’m proud of her. False pride usually causes the trouble between working couples, with first one on top of the heap, and then the other. But when you love each other . . .

“Of course it hasn’t been all roses,” Rory goes on. “And when we have an argument, it’s a real beauty. But when it’s over, there’s no hangover. We forget it. And that Lita—she’s such a doll, forgetting’s easy with her.”

Looking back over their first five years together, as he sees it, plurality presented the problem. “When you marry the whole scope broadens. You have to stop thinking ‘I’ and start thinking ‘We’.”

Thinking plural didn’t come too easy at times for a guy who’d lone-wolfed it through all his early years. “I’m going out to dinner with so-and-so tomorrow,” he would say casually. “You are?” Lita would reply with raised eyebrows. “Well, have a good time.” Then Rory would correct hastily, “I mean we’re going.” And she would smile, “That’s nice. I’m glad you told me.”

But how truly they were bound together as one was brought home to them poignantly when tragedy touched them for the first time—when Lita lost the baby around whom they’d woven so many plans and dreams. The doctor assured her she had nothing to fear, that there could be another baby another day. But more comforting and more steadying was Rory’s arm around her.

He’s ready to let the whole world know how much being bound together means to him. So much, he’s taking it in installments five years at a time to let it really sink in. “They’ll look a little out of style twenty years from now,” he laughs of the gray lace and the blue suit. “Folks will be saying, ‘Aren’t they a gra-a-an-n-d old couple,” he says mimicking in a quavery voice.

But how lucky can a guy be? his tone asks—a guy who five years ago watched a girl come dancing out onto the stage of the Mocambo into his life and his heart. “If you’ll trust me, I’d like to take you home,” he said and sensed from that night that he meant, “I’d like to take you—to our home.”

In his own way, Rory explained it to the minister who performed their first wedding ceremony, when he discussed their marrying again. Used to silver and golden weddings, the minister was surprised. “Isn’t this a little soon, Son?” he asked. “Maybe. But I still can’t believe it,” Rory said slowly. “That’s why I want to do it over again.”

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1953

No Comments