How June Haver Overcame Heartache

June found the card two days after John died, in a book about golfing. Memory slipped back to the sunny day long ago when he’d seen her off on a plane to New York. He’d brought her an orchid which she’d pinned to her coat, and the book. As she picked it up now, it fell open and there lay the card:

“To June, a sweet swinger. Keep swinging.”

Her breath caught. This was what John would have said, had he been here. This was like a little miracle. Else why should her hands have fallen on just this book, and why should the card have lain there untouched through the years? To June, it was a message from John as clearly as though he’d spoken. She took the card, and folded it between the pages of her prayerbook.

Sorrow comes to us all. For a girl so young, June’s had her goodly share. Yet she’s been granted a faith so pure and single-hearted that sorrow has come hand-in-hand with the courage to meet life on its own terms.

“When people lose someone they love,” she says quietly, “they’re likely to pity themselves. Why did this have to happen, they ask. You’re not supposed to ask why. Someday that question will be answered, but not here and now. Here and now you’ve got to be like a little child, put yourself in God’s hands, and take whatever He sends. It’s the only way toward peace.”

Because grief is the common lot, because others in grief may be helped through her story, June is ready to share it. Last August, she and John Duzik were looking forward to marriage and life together.

In the midst of their planning, John went to the hospital. His parents came down from Rock Springs, Wyoming, to be with June and him. The whole thing seemed safely over until, on Sunday, they took John back to the X-Ray room. June rode in the elevator with him, unsuspecting. But John, who knew so much about medicine, felt that something was wrong and that he ought to prepare her,

“I think we may have to go back to surgery.”

“Oh no! that’s not possible!”

“Yes, it is, honey.” He reached for her hand. “But we’ll come out all right.”

They took John to surgery a second time, a third time, they gave him the last rites of the church. He had his little joke with June. “I’ve got to go upstairs again, honey, wouldn’t you know it?” His mother bent to kiss him. He held her there for a moment. Speech was,an effort, but he had something to say.

“Remember that basketball game when the score was even, and I had to make the free throw? Remember it took me almost a minute? I was praying, Mom, and I made the point.” He smiled up at her. “You pray just as hard.”

They were all in the chapel praying, June and her family, John’s parents, his brothers and sister who had flown in from Wyoming, some of his friends and the nuns. They prayed out of the fullness of their hearts, but also as their faith and church had taught them. Not, “Dear God, if you’ll make John well, I’ll be good all my life . . .” They prayed in the spirit of Jesus at Gethsemane: “If Thou be willing, remove this cup from-me. Nevertheless, not my will, but Thine be done . . .”

A tap on June’s shoulder. “He’s still with us,” said the intern softly, “but that’s all.”

For what seemed an endless time, she stood unseeing. Then the fair head bent over the crucifix again. If this cup must be drained . . . “If John must die,” she implored, “please, dear God, please take him straight to Heaven.”

Then she couldn’t stand it any longer, and flew upstairs to the operating room. They were suturing the wound. June will never forget that moment, lifting her on wings of joyous thanksgiving. Because, in the interval, something had happened. For the first time in days there was color in John’s face. The bleeding had stopped. In his delirium he screamed, and even this seemed to please the doctors, for that morning he couldn’t have found the strength to scream.

But the improvement was temporary. Complications set in. For five weeks John hovered between life and death, and those who loved him, between hope and resignation. June had to go back to work. Every moment away from work she spent at the hospital, either in the chapel or in John’s room, knitting him a sweater. On the set, her eyes were forever turning to the phone.

She slept in the waiting room at St. John’s without taking her poe off. She was still praying that maybe a miracle would happen, though she knew it would have to happen very soon. As the nuns prayed, she rose from her Knees and looked at him. He’d suffered so much. Now he was smiling, his face relaxed and touched with a kind of radiance. Suddenly, as if a cloak had descended, her whole being was wrapped in such peace as she’d never known. “If you can look like that when you’re dying,” she thought, “then it must be that something beautiful is happening. It must be that God has answered our prayers and he’s going straight to Heaven.”

This sense of peace, beyond what the world can give, stayed with her through the night. It was a rare spiritual experience. “Someday,” she says simply, “I hope to get it back again. It’s as close as I’ve ever been to God.”

In the hospital chapel they celebrate mass at six. June wanted to get down there. Knowing that John would die soon, she longed to pray for him once more at mass. The service was about to begin, when again she felt the tap on her shoulder. “You’d better come up, June. Dr. Duzik has just died.”

In spite of this message she was confident now that John still lived—and she was right. With his hand between hers, he died at twenty minutes past the hour.

Now the long vigil was over, and life had to be faced. With all her religious ardor, June remains human. There were moments when grief threatened to overwhelm her. As when she returned to John’s room to gather up her belongings and found the sweater she’d been knitting for him. She went back with his folks to Wyomings Watching her, Mrs. Duzik said gently, “Cry, June. Because God made tears, too.”

John’s mother is a wise woman. Something was on her mind, and she waited for the chance to say it. It came after she’d washed June’s hair one day. Standing behind her, massaging her neck and temples, Mrs. Duzik spoke in quiet tones of her son. How lucky they’d been to have him, if only for a while.

“But, June, I’m older and more experienced than you. I know that John’s place in your heart will always be there. Only, I want you to remember this always. Don’t be forever comparing others to John, to their disadvantage. Like all humans, my son had plenty of faults. Don’t put him on a pedestal. It might ruin your life.”

June feels no self-pity and doesn’t want pity from others. So she shrank from returning to Warners, where there were still publicity chores to do. Going back to Twentieth would have been easier. At Warners she’d meet the people who’d shared her day-by-day ordeal. If they were overly sympathetic, she might break down. It was all right, though. People understood. Nobody said too much. “You look thin, June . . .” Or, “I hope you’ll get some rest.” They were kind of matter-of-fact and she blessed them for it.

Her most difficult moment came when she closed the door of her apartment behind her. Up to now she’d been borne along by all that needed doing, surrounded by those who loved her. Now she was alone, and wherever she looked, she saw John—in the shelves he’d put up, in the books he’d given her, at the table where he’d. tucked away her first meal. “Honey, I thought I was going to marry an actress, I’m marrying a cook!” The ring of the phone knifed through her. When the phone rang, it would never be John again. If she hadn’t known desolation, she’d have been less than flesh and blood.

Suffering must be borne. It can be borne in many ways. It can enlarge or diminish the sufferer. Instead of rebelling, June accepted her pain.

Her creed teaches that absorption in sorrow is selfishness. June acts as she believes. Though your hearts heavy you have no right to impose your burdens on others who have burdens of their own. To the world, she presented a cheerful face. To lose herself, she tried to do for others and found that the doing brought its own satisfactions. As often as possible, she’d go out to sing to the boys at Birmingham Hospital. She wrote to magazines that might have pictures of John, and started a scrapbook for Mrs. Duzik. Jim Hogan, who was to have been best man, told her of his mother’s work with the children at Juvenile Hall. Would June like to help? She would and did, and fell in love with a pair of blonde twins who yelled to go home with her and whom she’d have taken if she could.

Her sisters’ children have been a godsend. “Sometimes I don’t know what I’d have done without those babies.” She welcomes the chance to sit with them when Dorothy or Evvie want an evening out with their husbands. They adore her, and why not? She’s Cathy’s “horsey” and trots her ’round the place till she gets a stiff neck. At Evvie’s, she keeps a pair of red sleepers exactly like little Brian’s and climbs into them, come bedtime, which enchants him. In the morning she gives him his bath and pretends he’s hers. For the first time a wistful note creeps into her voice. “I’d love to adopt one, if I don’t get married.”

Which is as good a place as any to scotch the story, started by Winchell, that a boy named Joe Campbell would eventually be June’s husband. Joe Campbell is a friend of hers, introduced several years ago by her sister and brother-in-law. What she chiefly regrets about the rumor is that it caused embarrassment to Joe. For herself, she’s been too long in the business not to realize that columnists are bound to let fly in the hope of hitting a bulls-eye. Such things don’t bother her, they’re not important.

She’s glad to be working with her good friend, Gloria De Haven, in “I’ll Get By,” her current picture at Twentieth. She’s glad ‘it’s a musical. June feels that what she has to sell is happiness.

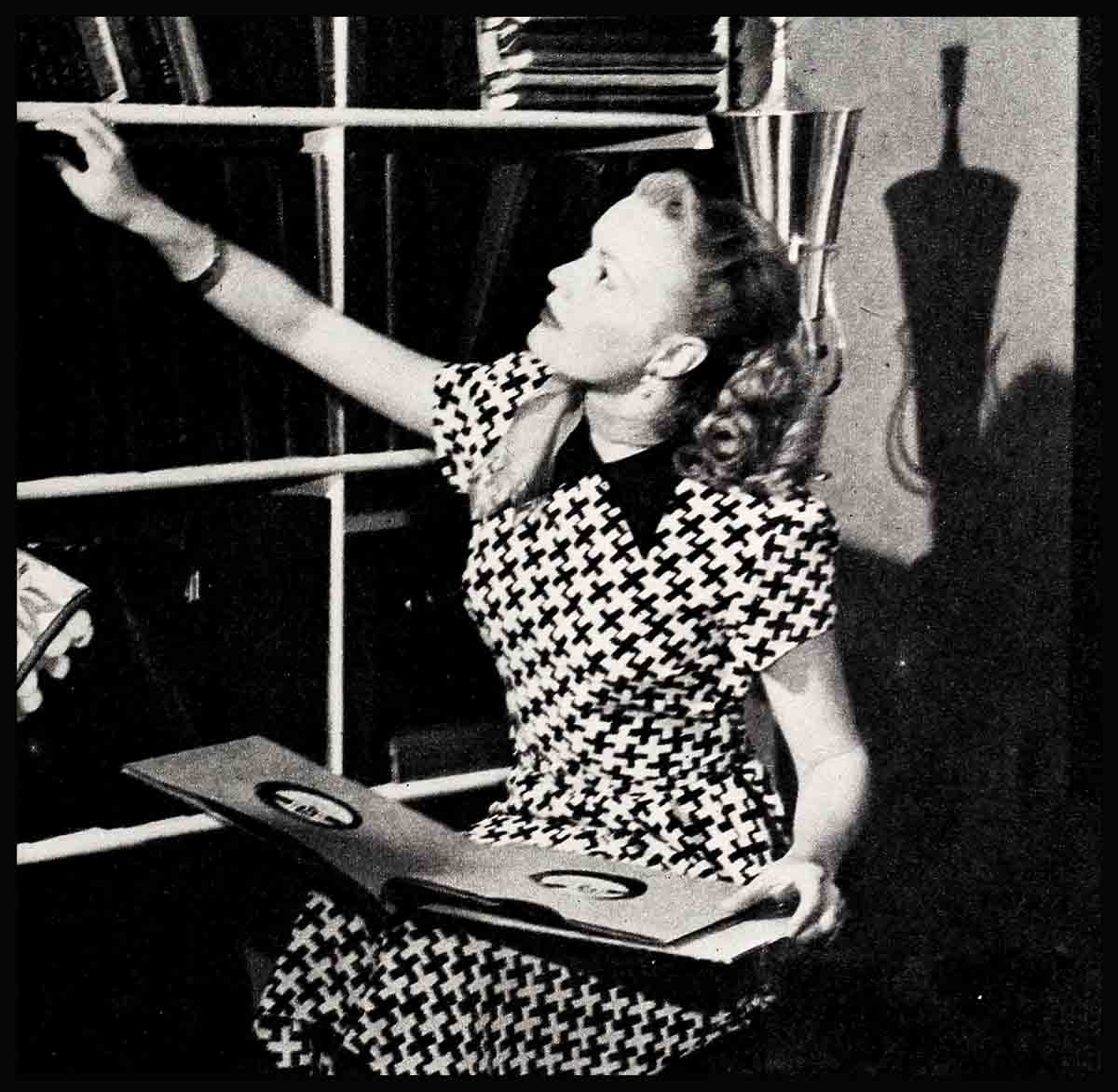

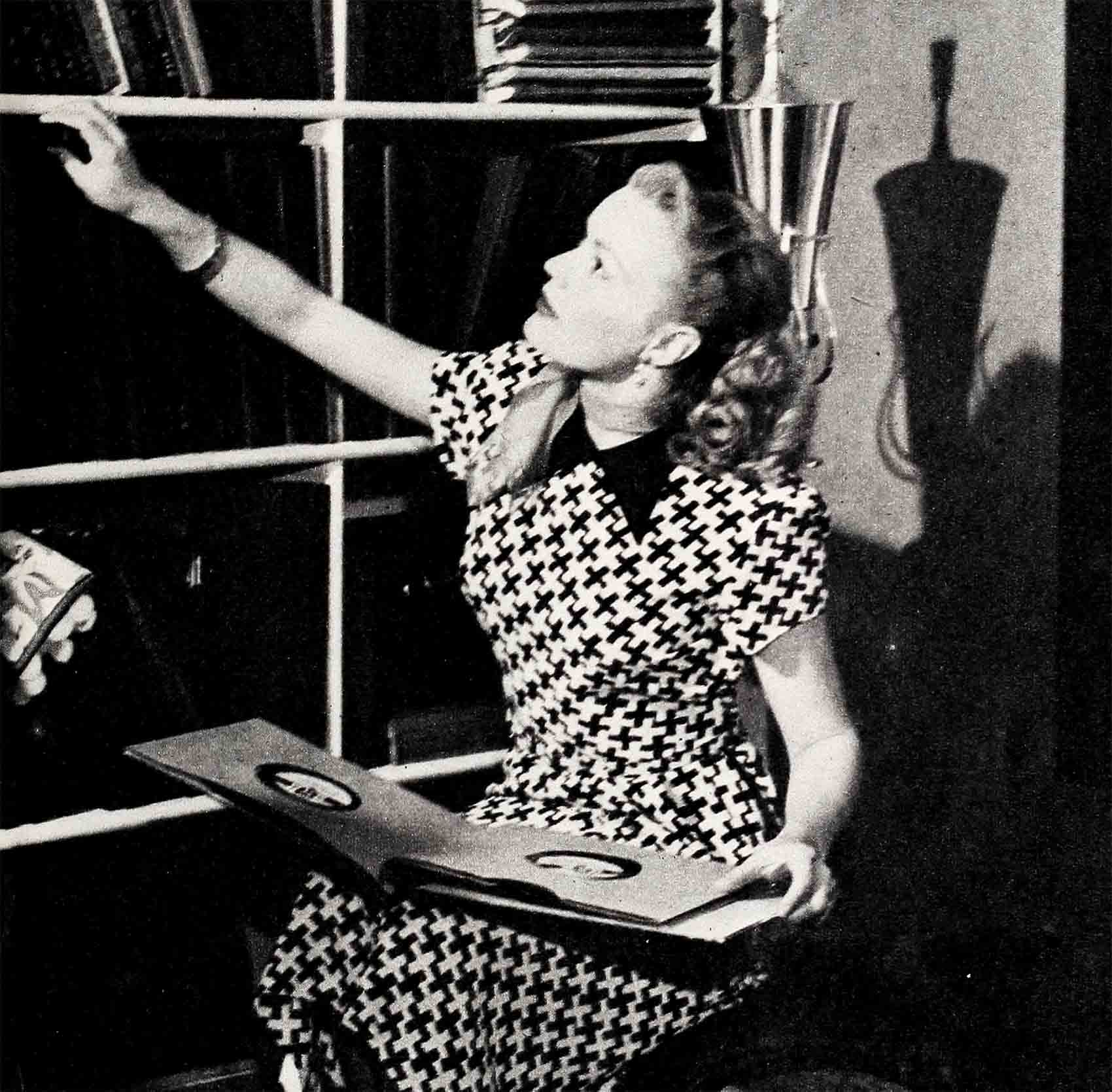

All these things have helped. Most of all, she’s been helped by her church and its teachings. She owns a large library of religious books, well-worn by use. Since John’s death, she reads them more constantly and feels especially drawn toward St. Teresa.

“She was so young. She died when she was my age. Her life proves that you don’t have to do great things to win grace. With her, it was just the little everyday sacrifices. I read a letter of hers that seemed to speak straight to me. She said they marvel in heaven that we can give the name of death to the commencement of life. That letter meant a great deal to me.

“When you’re hurt,” she explains, “you pray harder than you’ve ever prayed. In the world, listening to others, you can’t always hear God. But in the quiet of a church nothing comes between. You can talk to Him as you would to your own father. Getting close to God is the only way I know to get close to John. But it never entered my mind to take the veil. For girls who have the vocation, I think it’s marvelous. Only I don’t have. God hasn’t chosen me.”

Some things she still isn’t able to do. In Wyoming, she couldn’t bear to go to Jackson’s Hole where she and John planned to build a ranch. Here she avoids the golf course. John gave her her clubs and started her on the game. She cant bring herself to go near the Country Club, where they last played together. But she will someday. John wanted her to.

In a special drawer lie some of the ties she bought him. June has always liked men’s ties for their color and design. Soon after they started going together, she took two to John’s office. They made a powerful hit. “From now on,” he proclaimed, “you pick out my ties.” Of all his possessions, June wanted only the ties. Some, she gave away to close friends of John’s. The rest she keeps in this drawer.

With all the help her loving spirit acknowledges, she doesn’t pretend that the way has been easy. When it seems too hard, she tries to think back to the night before John died and the miraculous sense of peace that enveloped her. It gives her heart to go on, “When tragedy strikes and you feel you can’t bear it, you find, years later, that some good has come of it. Some Contains good has already come to me.”

She lifts her clear-eyed gaze. “The active anti-people I’m sorry for are those who don’t believe in God. John was here one minute, and gone the next. The John I loved, the soul of John wasn’t there anymore. All the clever people with all their clever ideas can’t explain where it went. I know it went to God.”

Her Lord is June’s Shepherd. He brought her whole through the valley of the shadow.

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITTIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1950