It Should Happen To A Lemmon!

From the dimmed sidelines of the stage, an eager young actor, in the costume and make-up of a middle-aged English bobby, stood alerted and anxious as he waited for his cue. It came in the last few crucial moments of the last act of “Angel Street,” just in time for him to enter and arrest Francis Lederer, the husband with murder in his heart. . . .

The young actor admitted he was nervous. After all, it was his first role with a real star like Lederer. True, he didn’t have a word to say—but he had action. And his role was tricky. After all, he didn’t get a spoken cue. Nope, he had to count his entrance—from the time Lederer turned his back and started walking off the stage towards the door. Timing was all-important—poor timing could ruin the scene. Awfully important, he mumbled to himself as he kept his eyes glued on Lederer. There, he’s turning his back, get ready. . . .

The young man made his entrance and timed it to the split second—perfectly. Then, in his enthusiasm, he jerked his head sharply and the bucket-like hat slipped down over his eyes. He couldn’t see a thing and he couldn’t budge the jammed hat. All he could do was grope—and listen to the howling of the audience. Finally, the fleeing Lederer, for plot purposes, saved whatever was left of the scene by running smack into his arms instead of out the door. And the audience, which was supposed to be screaming with suspense, applauded in good-natured glee.

Today, Jack Lemmon still insists “that was the biggest laugh I’ve ever had in my life,” despite he fact that in one brief year of movie-making he’s won the reputation of an expert laugh-getter.

Ever since his first picture with Judy Holliday in “It Should Happen to You,” Jack’s been hailed by critics as the brightest and best of the new cinema comedians.

In trying to explain Jack’s success, you first have to know him. Yet to describe him is difficult. He looks like a young eager lawyer or perhaps a bright, up-coming bond salesman. His conversation is sprightly but cultured; show-business jargon crops up sparingly but effectively. He’s had the advantages of a well-heeled and socially active family who saw to it that his education took place in private schools and at Harvard. And despite the fact he calls Hollywood home, there’s more Harvard gloss on him than Hollywood. Yet he’s an actor to his fingertips. He loves his work and works hard.

He offers the casual appearance of built-in brains and gentility. When a studio executive told him he had the asset of not looking like a comedian or even like an actor, Jack replied, “No actor looks like an actor anymore.” The line has been quoted frequently, often with a suggestion of slight disbelief.

“I don’t understand why people are surprised that I said that. I was referring to the matinee-idol—in the live theatre. I remember as late as my teens, the leading men I saw were always the long, wavy-haired, flamboyant, Inverness-cape type. But in the movies, this isn’t true. A man may look like a truck driver and be a leading man. The matinee-idol type is a thing of the past,” says Jack.

Tall, slim, with black hair that’s straight and certainly not long and wavy, Jack knew acting from every angle—stage, radio, TV—all before he clicked on the big screen. He feels very earnestly that to last as a star it’s much easier if one has such training and background.

“It’s much harder for the actor who is pushed and rushed into sudden stardom. This is a highly competitive business. There are always eight thousand people just as good as you are. It can happen that a person can become a star without great talent and training, but it’s mighty tough for him to meet the competition.

“If my son Chris wants to go in the entertainment business when he grows up, I’ll never object—if I’m sure he couldn’t be happy without it. It’s not enough to like it. You’ve got to love it. The theatre is too tough; too much depends on luck. It’s not like any other business.”

One of Jack’s first jobs after graduating from Harvard was in a not-so-swank New York night club, The Old Knick. He played piano, wrote comedy skits, sang, danced, was m.c. and comedian. He did just about everything except roll out the empty beer barrels.

“That was the luckiest thing that ever happened to me. Ordinarily young entertainers have no place to learn as they work. As George Burns has said: ‘Actors have no place to test their material and capability. No place to be lousy.’ The break-in circuits of vaudeville and the many touring stock companies of years ago used to afford this training. Now where do you get it, unless you’re lucky as I was? It was the greatest.”

During Jack’s early struggling days in New York, he declined offered financial assistance from his father. He lived in a seedy one-room apartment, which he asserts had two definite advantages. It was over a delicatessen and was big enough for a piano. He’s an expert on the eighty-eight and also has written many songs.

“They’re not commercial—or at least haven’t been up to now—because they’re show tunes. One time I sold an option for an entire score, but the show never was produced. Maybe someday,” he adds hopefully.

“Playing piano is a necessary outlet for me. It’s relaxing. I usually play for a while when I get home from the studio at night.”

He also plays harmonica and ukulele. He and Jimmy Cagney spent hours strumming ukes when they were on location on Midway for “Mister Roberts,” in which Jack plays Ensign Pulver. He idolizes Cagney.

“What great all-round talent he has. Not just acting and dancing. He paints, plays guitar, writes brilliant and sensitive poetry. And he has such heart. He spent hours teaching me to hoof. He’d give me all sorts of tips on doing scenes. Then, of course, he’d take the scene right away from me. He can’t be topped.

“l’ve never worked with finer people. I asked Hank Fonda, who plays the name role, if he ever got tired of playing Roberts after something like a thousand performances on the stage. He said, ‘I always liked Wednesdays and Saturdays because then with matinees I got to play it twice.’ That’s what I mean about lasting stars. They love their work.”

Director John Ford and producer Leland Hayward of the “Roberts” company believe Lemmon has this same quality. They’ve even said so for publication. Hayward adds, “Jack is dynamite. He’ll be a big, big, big star.”

This dynamic young gentleman-comic was born on February 8, 1925, in Boston, and named John Uhler Lemmon III. His father, now vice president of the Doughnut Corporation of America, was officially in the baking business, but show business was his hobby. As a boy he had sung and danced in minstrel shows, later in life got kicks out of playing benefits. At the age of four, son Jack joined him and made his debut in a melodrama entitled “Gold in Them Thar Hills.”

While Jack was attending Phillips Andover Academy, he spent summers with stock companies in New Hampshire and at Marblehead, where he gave that provocative performance in “Angel Street.”

“At Harvard I spent so much time on music and acting I always had to cram for exams; I just got through. I was no honor student. But I had a good time and got a lot from life there. It was a living ball through school and college. And I don’t think this was a mistake. You can get knowledge by reading books at home. I believe at college you learn by growing up with people, just as much as through academic learning. I wouldn’t have missed any of those extra-curricular activities.”

Among other things, Jack was vice president of the dramatic club and president of the Hasty Pudding Club which produces musical comedies. (He recently was awarded a plaque by the society citing him on his “elevation to leading man in the nation’s brightest entertainment medium.”) In addition to college-produced plays, he worked with the Abbey players from Ireland when they spent a season in Boston.

After serving as an ensign in the Navy during World War II he returned to Harvard for a year of graduate study, then went to New York. There in 1948, while acting in a little theatre production of Tolstoi’s depressing “Power of Darkness,” he had an experience far from depressing. He met beautiful, blond Cynthia Stone, a young actress from Peoria, Illinois.

“She was an ugly, dull girl who chased me for two years, so finally I married her,” is Jack’s reverse way of describing his courtship of his adored Cyn.

Cynthia was a successful radio actress and coached Jack on microphone technique. Soon Jack was working regularly in soap operas. Quite by chance, Jack and Cynthia were cast opposite each other in one of these and worked together for twenty weeks. They were married in Peoria on May 7, 1950. For seven months shortly after that, they did “The Couple Next Door” on ABC-TV.

The ambitious young couple next incorporated legally as Jacyn Productions and sold their own packaged TV show “Heaven for Betsy” to Lever Brothers on CBS. They still own the property.

“But actors shouldn’t try to handle finances which you have to do on a package deal. It’s too much of a headache. I’ll never try it again,” vows Jack who produced as well as starred in the series.

Jack and Cynthia were on a fishing trip in the wilderness a hundred miles north of Montreal when they were summoned back to New York because their show was sold by their agent.

“We were out in the middle of a lake when a voice from shore called ‘Jacques LeMond.’ It seemed fantastic, being paged that way. At the lodge we managed to understand, with our smattering of French, that I was to drive to La Berriere, Quebec, to the nearest phone—ten miles—and call New York. The operator there spoke only French and she didn’t seem to understand my French at all. It was the most fantastic relay you ever heard until I reached the William Morris office in New York. Then our agent merely said, ‘Come Home!’ ”

Jack and Cynthia still love fishing, someday hope to buy a shack in the High Sierras as a base of piscatorial operations.

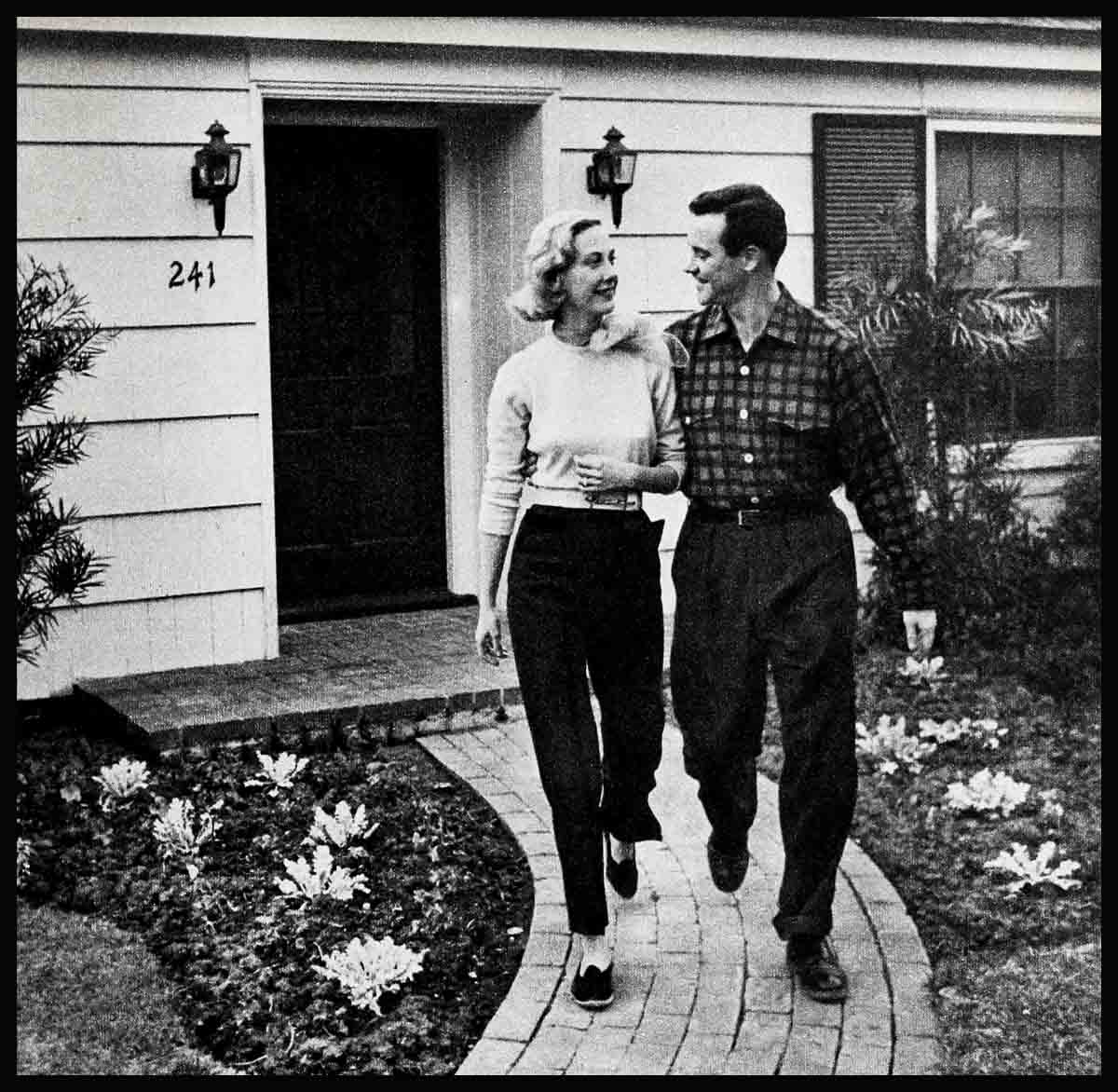

Today they live in a white colonial house in Brentwood, which Cynthia has decorated with charming warmth and taste. There is a happy blend of contemporary and traditional, with fine antiques and gleaming silver. Jack has a baby grand piano. The dining room is especially attractive, with French mural wallpaper depicting scenes in Paris. In place of a large dining table there are three small glass-topped tables, giving the effect of a sidewalk cafe.

There is no swimming pool in the large yard and this leaves plenty of room for Jack’s newly acquired passion—gardening. Although he considered himself a confirmed New Yorker, and admittedly misses many things about Manhattan, he now enjoys his suburban life. He’s become an expert on roses and currently is “getting happed on camellias and azaleas, too.”

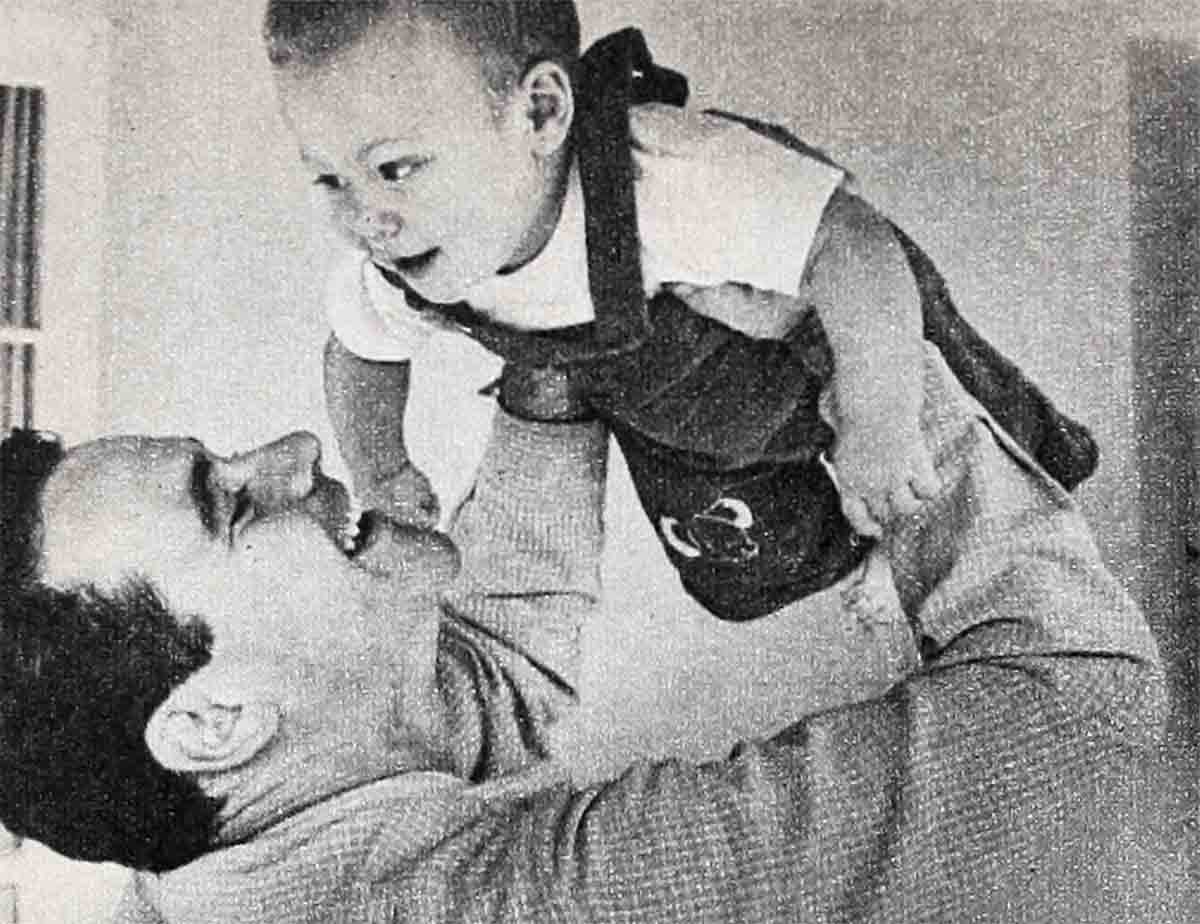

Jack says quite frankly, that his main hobby is son Christopher, born last June 22. This adoring father will talk about his son without getting a cue.

“He’s such a wonderful baby. So good, healthy and big! He weighed nine and a half pounds when he was born and before he was six months old needed size one clothes, but he isn’t fat. He has blond hair and gray-blue eyes. I think he looks like Cynthia, which is wonderful because she’s slim and blond and a beautiful girl.”

Jack and Cynthia named their son Christopher solely because they both liked the name. No family reasons.

“Not for anything would I have named him John Uhler Lemmon IV. Why, as John Uhler III I had to be a ham by the time I was eight,” says Jack, His eyes bright with mirth, the same Jack who flatly refused to have his name changed when he signed his contract with Columbia Pictures. (“I guess they were afraid people would gag that the studio had a lemon in Lemmon.”)

In the little time he has for hobbies—he’s jumped from “It Should Happen to You,” “Phffft,” “Three for the Show” and “Mister Roberts” into “My Sister Eileen” with no time between—he’s trying to take photography a bit seriously—“only because of Chris, so we’ll have a photographic history.”

Jack likes golf, enjoys night clubs occasionally but prefers small parties at home. He likes to dance and go dancing, but Cynthia, unlike most wives who have to urge their husbands, doesn’t care too much for dancing. Jack has a prodigious memory, reads more than the average, on a wide variety of subjects. He dresses conservatively. He is. neat by instinct; Cynthia doesn’t have to pick up after him. He likes to cook and is a good cook. He has great admiration for his father.

“Dad was never a professional dancer, but he’s always been mighty good at soft shoe. One time he even danced at a benefit with the late Bill Robinson. Dad was no Bojangles but he did all right. He has always said when he failed to find romance in a loaf of bread he’d retire. He always loved his work and obviously still does, because he tried to retire last year and went right back to work. He’s been opening new markets for doughnuts in Europe. Did you know doughnuts are going big there now?”

Obviously Jack has inherited his father’s verve, his zest for life, a dedication to the work of his choice. And you can bet your best spring bonnet that John Uhler Lemmon III will always find romance in his work of getting laughs.

THE END

—BY DOROTHY O’LEARY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1955