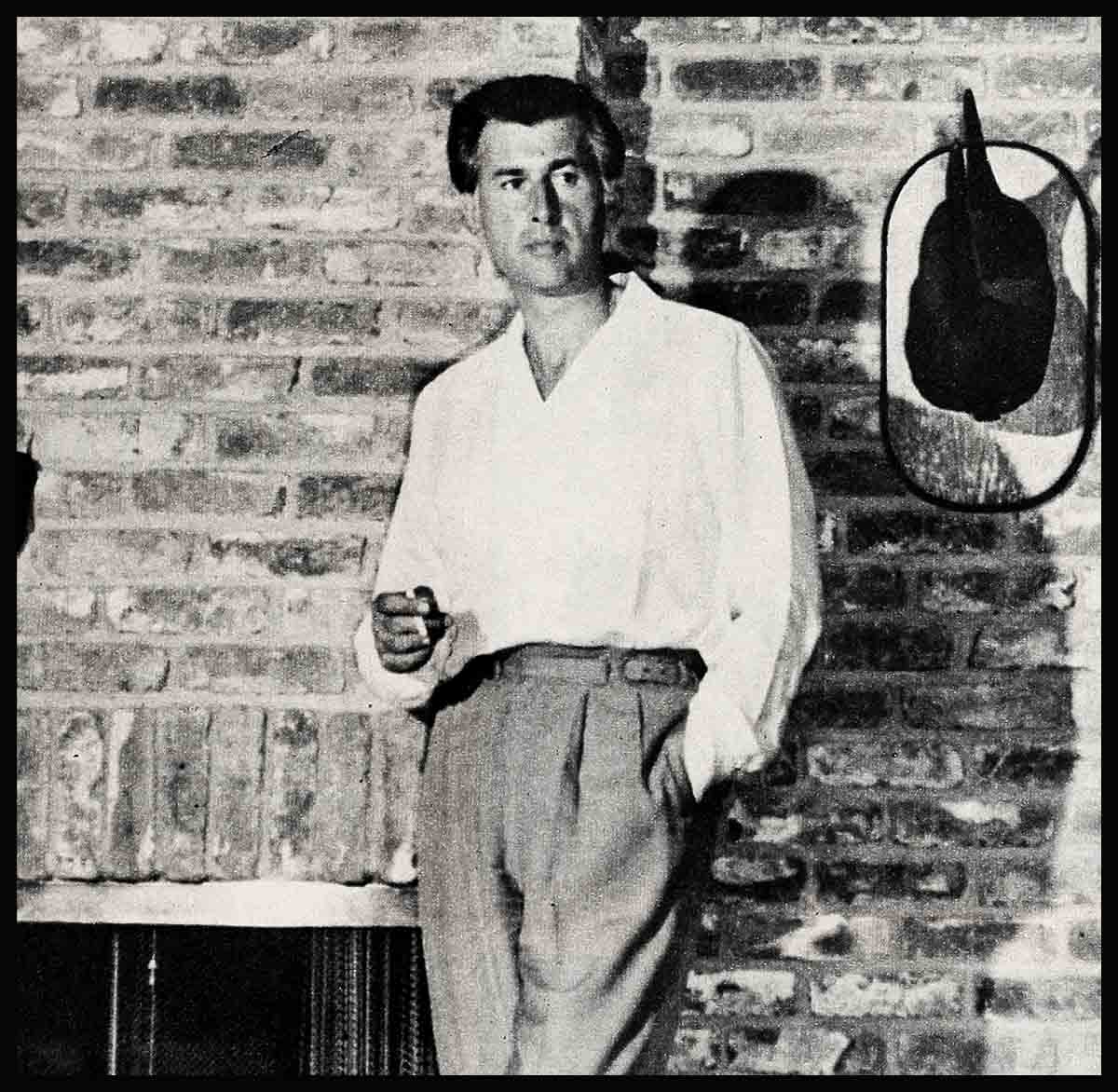

This Is Stewart Granger

This man Granger lives on the peak of a very high hill. From wherever he strolls on his land, or wherever he stands in his house he can look down. He can see few houses or people or other signs of life. In the summer he can see brittle, gray brush, sandy patches of wasted-away hillside, sunburned slopes of tarnished grass and an occasional stray animal. In the winter, when the rains have carried new life from the watersheds to the valleys, he can see an abundance of green, flourishing small trees and bushes alive with exotic shoots and sprays of color. And small deer feeding, and chipmunks, and in the evening, coyotes.

If Stewart Granger is an arrogant man this house on his mountaintop could be the cause of his remoteness, his separation from other people, his lordship over the natural things he sees. It is easy for even a timid man to grow superior when all competition is out of sight. And easy to carry the feeling down the turning roads to the city.

It was to find out if Stewart Granger is truly an arrogant or a medium-tempered or a mild-mannered man that I went to his house on the hilltop.

It was quite early in the morning. When I got beyond the last of the residences I came to a large white gate which was opened and began a steep climb on a newly-paved road. Ahead of me stood the house, perched like a picture-post-card Swiss chalet on an Alpine summit. It was the shade of aged, unpainted oak, and the sun glistened on the windows that seemed the entire wall on all sides. I drove into a courtyard and parked close to a low wall of natural rock that separated the property from a chasm that plunged 500 feet straight down.

Stewart Granger stood in the doorway in a pair of white shorts. He is tall and tanned and well filled the entrance. He wore no shoes, and not wishing to tackle the hot macadam of his driveway, motioned for me to enter.

I followed him into a very large living room, furnished low and for comfort, and sat in a chair upholstered in zebra skin. Above a knee-high dado the walls were clear plate glass, and above the glass hung hunting trophies; skins and heads, and over the fireplace a monstrous ram’s head. It was a man’s room, but scattered about were small implements of beauty culture and feminine bits of crystal, minute ash trays and tiny clusters of bric-a-brac that said the man lived with a woman. Predominant, though, was the ram’s head, which I learned later was the crest of the family.

Although it was very early I was offered a choice of whisky, beer, a soft drink or coffee. I chose the coffee, and in a moment a servant brought a glass decanter of the stuff simmering over a candle warming-oven. Granger apologized that it was too strong and ordered hot water. He drank it straight.

Then the man’s wife came in wearing a pink wrap-around robe. She was barefoot, too, and her hair, trimmed in the manner of an Italian urchin, was awry but very fetching. On the screen she’s Jean Simmons. On the hill she’s Mrs. Granger, so she sat, visibly content and out of the way on the floor at the man’s feet. She also had coffee, watered.

“What’s the guff?” said Granger. “What could you possibly want to know that would bring you all the way up here so early in the morning?”

“I want the answer to a question,” I said. “The title is, ‘Stewart Granger—Is He a Man Or a Louse?’ ”

Mrs. Granger rolled back on the floor and had her first laugh of the day. “Let me answer that,” she said.

She was ordered from the room. Granger got up and walked about looking down into the valleys. “I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe I’m not the one to ask.”

“Who better?” I said.

“Who says I’m a louse?” Granger asked. Then, hurriedly, “Don’t answer that. It might take too long.

“Look,” he said, “why don’t we just talk? Ask me anything you like. Then make up your own mind.”

Mrs. Granger came back in and poured us all another cup of coffee. Now she had on a crazy pair of knee-length trousers and a shirtwaist. Her husband grinned in appreciation and let her remain.

There was a lull, a real thick lull that hung on and I had a chance to remember the things I’d heard about Granger, the louse. There was an article in an English vag which had taken Granger apart for fair.

In this piece the writer had either been caught on an off day, had been suffering from boils, or just plain hated Stewart Granger. He stated that Stewart Granger’s manner was making him the “most un-popular Englishman in Hollywood.” But there was nothing so pernicious in Granger’s manner as he plodded about his own living room.

Continuing, I recalled that the English writer had said some other very unflattering things about Mr. Granger. “His critics,” said the writer, “say he is overbearing and superior. Granger is beginning to grate—and without the saving grace of success. The man who signed with M-G-M as the heart throb of 1950 is fast becoming their pain in the neck of 1953. . . .” And then he accused Stewart of looking down on the small fry of Hollywood and “walking about as though he had lost a swimming pool or something.” It was a most unflattering article.

“Are you aware,” I asked, “that some people consider you a snob and dislike you?”

“Of course, I am,” Granger said lightly. “But I’m not going to let it bother me. I don’t think I’m a snob. My friends don’t think I’m a snob.

“My wife and I,” said Granger, “subscribe to some views that might be misunderstood and lead to unpopularity. For instance, we were both tremendous movie fans when we were children. We both loved the air of mystery that hung about movie stars. We thought them beings apart from ordinary people—and liked them that way. And we had no inkling that we would both be in the same position when we were older. We were idolators without envy. Our opinion hasn’t changed. I think that for the good of the movie industry a star must be different; he shouldn’t trot about having dinner with strangers, be seen sitting on the curb at parades, hang about corner drug stores or have his picture taken washing his own socks. It happens that Jean and I would like to do these things, but we avoid them. So we are snobs. Our friends know we’re not—and you’d think people in Hollywood would understand, but apparently some of them don’t.”

Granger said it like a speech at first, then he sat down and spoke with obvious sincerity. His wife padded about filling coffee cups and nodding approval.

“And another thing,” Granger said, “is that we like to stay home. Id hate this to get around, but I’m a simple man who likes his home and loves his wife. I prefer to come up here after a hard day’s work and loll around watching television or swimming in the pool, rather than go out and be seen in public. And we have our friends up on week-ends for barbecues. If that’s being anti-social, so are Greek fishermen and cowboys and steel workers. They live the same way.”

“Are you a trouble maker?” I asked.

“What kind of trouble?” Granger said.

“There you have me,” I said. “But it seems to me that I have read a good deal about you quarreling and bickering with people at the studio, on the sets and such.”

“Name an instance,” Granger said, standing up again.

“Let’s change the subject,” I said.

“Let’s not,” said Granger.

“Well,” I continued, “I heard once that you got pretty salty with a reporter one day in the M-G-M commissary.”

“That I did,” Granger admitted. “I was having lunch and he came and asked me if I was separating from my wife. I merely suggested that he remove himself to a warmer climate and offered to help him on his way. And I believe I suggested he change his name and offered a few rather uncomplimentary selections.

“It’s odd,” said Granger, “that even the people who live in Hollywood cleave to the stupid belief that the only way a man can prove he loves his wife is to gaze into her eyes like a spring-struck boy every moment they are together. My love for my wife is genuine, but if it takes my fancy I might chase her down Hollywood Boulevard pelting her with marshmallows.”

Jean got to her knees and assumed the position of a runner waiting for the crack of the starting gun. She knew the man better than I did and obviously believed the marshmallows were on the way.

“I’m possibly the romping kind of lover,” Granger continued. “And I get pretty tired of trying to conform to other people’s idea of how a man should publicly establish his affection. I suppose we’ve had cross words—but never in public. It’s all been horsing around—stupidly misinterpreted.

“I know that a movie star is constantly in the public eye, and that the people who make his fine life possible are entitled to a more than ordinary interest in him and his personal and professional activities. He gets paid for that. But I do think that a reporter, or observer, shouldn’t make his own decisions as to the meaning of the actor’s conduct without first discussing it with the actor. I could walk into a department store and pick up an object I wanted to buy and if you saw me you might accuse me of being half-way through a bit of shop lifting. But if you’d stick around and watch me pay for it when the clerk came, it would be an entirely different story. If you saw me in a cafe and I gave my wife an affectionate pat on the back of the head, you, according to your choice of conclusions, could call it a tender gesture or claim I had slugged her. It’s the half facts that can crucify you.”

It sounded as though Jean said, “Yeah, man,” but she couldn’t have. She’s pretty British.

“This conversation,” I said, “is degenerating. You seem to be explaining everything.”

“Aha!” Granger said, like he did in “Scaramouche.” “It’s not the truth you’re after at all. It’s not ‘Is Granger a Man or a Louse’— but ‘That Louse Granger!’

“You ask me a lot of questions, which I answer willingly, while you drink me out of coffee, and you’ve probably got all the answers already written down.

“I have been accused of just about everything from tripping waiters to losing all M-G-M’s money on films like ‘All the Brothers Were Valiant.’ I know this is one of the hazards of the game, but you can’t blame me for getting angry about it once in a while.”

I got to my feet, saying, “I came here to ask you some questions and I have the answers.”

Granger got to his feet. “And what are your personal opinions?” he asked.

“Well,” I said. “I think you’re a man with a good deal in his favor and your wife is very beautiful and you have a lovely home here. And I think you’re a splendid actor—and so is Mrs. Granger. And I think people have been shoving you around without reason. I don’t believe you’ve ever tripped a waiter—and I think you’ve made M-G-M a blinking fortune.”

“Well said,” said Granger.

“Well said, indeed,” said Jean.

“And what’s more,” I said, “you are one of the happiest couples I’ve ever met, and. . . .”

“Why don’t you stop when you’re ahead,” Granger said kindly.

I got into my car and started out of the courtyard. The Grangers stood watching me from their doorway. There is a steep cliff at the turn of the driveway that plunges down to a rocky chasm, and only a narrow wooden rail fence separates you from disaster.

“Don’t forget to turn right,” Jean said. And I remembered the picture I’d seen her in where everyone in the cast was dashed over just such a cliff as this. I didn’t give her the courtesy of a thank you. I made the right turn quickly and roared down the mountain.

(Stewart Granger is in “All the Brothers Were Valiant” and Jean Simmons is in “The Actress” and “The Robe.”)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953