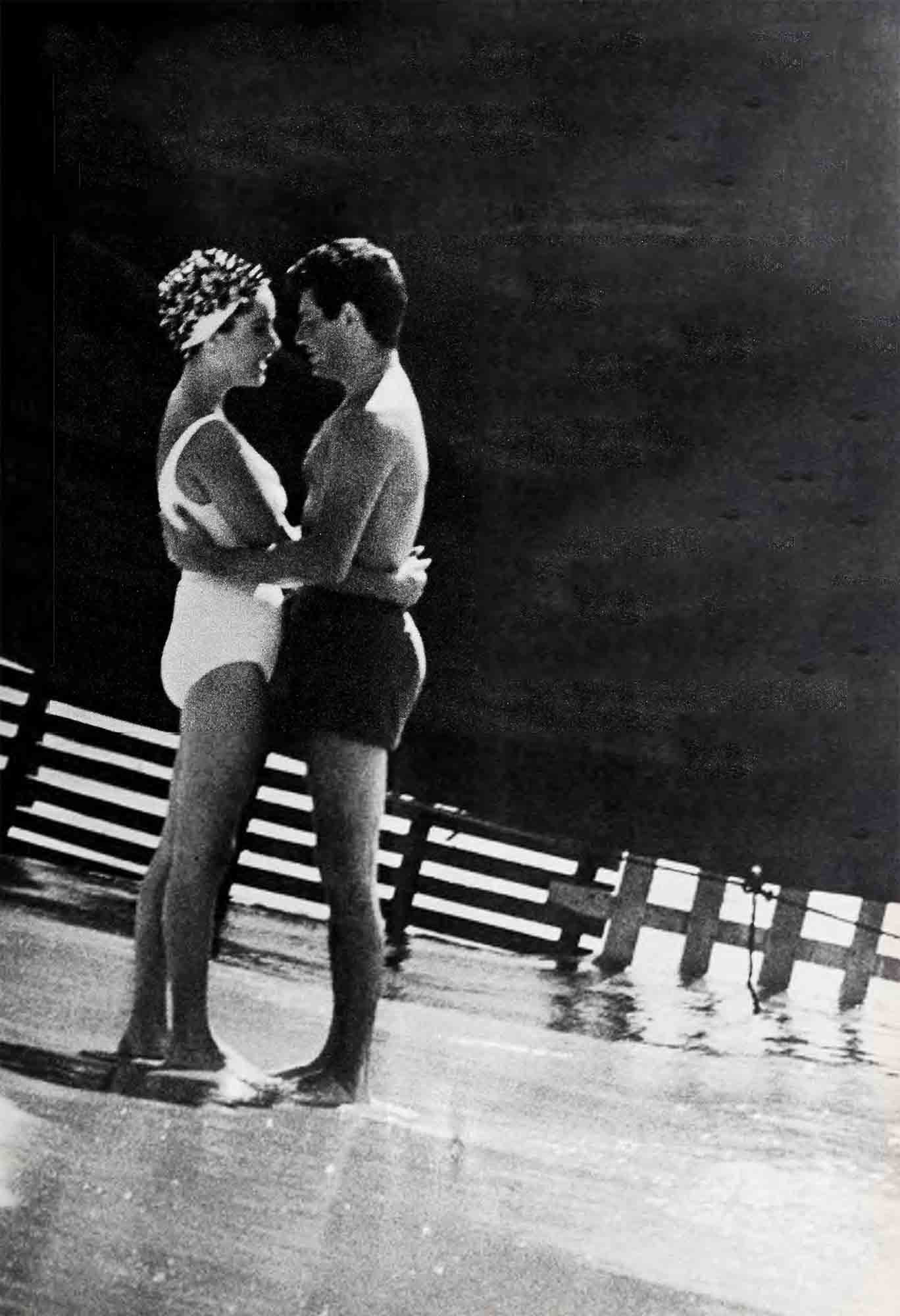

Elizabeth and Eddie’s Second Honeymoon

Why Liz and Eddie had to have a second honeymoon

The feel of Eddie’s arms around her waist only seemed to make her shiver even more. It was as if the burning sun overhead had become a cake of ice—as if Eddie weren’t the husband she loved, as if every stranger were someone to frighten her. They’d left, less than fifteen minutes ago, their six pieces of oversized luggage piled in the corner of their “honeymoon” cottage and, without even unpacking, had started to run hand-in-hand down to the beach for their first swim in the lovely blue tropical sea. Then Liz had stopped short. “Let’s go back,” she said suddenly. “I don’t want to swim after all.” They walked back slowly, neither of them speaking. Eddie watched her face worriedly. He knew by now what could cause a bright mood to fade and make Liz’s face grow pale with fear. There had been many times he’d seen that haunted look. Sometimes it helped to talk it out between them, and so he asked softly, “Liz, what’s wrong?” She walked into the cottage and then, hands dropping helplessly to her side, she cried out:

AUDIO BOOK

Eddie understood. . . The whispers seemed to follow them. And, though he might put his arms around Liz protectively and she might hide her face in his shoulder, they were, both of them, helpless to stop the whispers; to answer them.

There had been that day in New York, cold and with a dampness in the air, as if it might snow, even though it was early spring. Liz had bundled her fur coat around her, trying to keep warm, as she waited for the next location take of “Butterfield 8.” The Greenwich Village street had been closed for the shooting, but a curious crowd had gathered at the edge of the barriers that had been put up. And, then, as everyone quieted down for the take, a woman’s voice yelled out from the crowd, vile, obscene words. They were directed at Liz and she had wanted to run away from the sound of them. But, then, how many times can you run away? And so she stayed and did her scene.

And there were always others. . . . Like the woman at the airport in Jamaica, her voice harsh as she said, “Their second honeymoon? Why, I’ll bet they’ll be calling for the kids or their friends or anyone to join them the very next day. Why, the idea of their being alone together, for any amount of time, probably scares them to death. They have nothing in common. You know that neither of them wanted this marriage, it was only because of the scandal. Just look at her. She said she was going to give up pictures, and she’s making more and more. And they’re always on the go—New York, Vegas, London, Palm Springs, Hollywood. If they ever stop running for a second, they’ll find out the awful truth: they have nothing in common . . . except maybe Mike Todd’s memory. . . .”

The woman stopped as if for breath, and then suddenly looked back over her shoulder. The smile fled from her face and she blushed a deep crimson. There, standing at the gate, was Elizabeth Taylor. She had heard every word. Eddie was with her this time and his face white, he began to take a step toward the woman. But then, as if changing his mind, he’d looked at Liz helplessly, apologetically. It was hard for him to escape the thought that hadn’t he brought this all upon her.

Liz had only stared at the woman for a second, not in anger, but with such an expression of deep sadness and pain, that it hurt him more. Then, as if the woman had not been there at all, Liz followed Eddie into a cab and settled back in the seat—shivering even though it was a warm night—as he gave the driver the address of their honeymoon cottage.

Eddie’s voice brought her back to the present as they stood in the middle of the cottage living room. “. . . a penny for your thoughts,” he said, trying to change her mood by laughing and asking, “What’ll we do now?” Shaking his head ruefully, he looked at the six large pieces of luggage piled in the corner of the living room. “Unpack?”

And then she laughed. This time she laughed freely. “Eddie, you know what? When you look like that . . . you look like a chipmunk!”

Eddie sucked in his cheeks, to help the resemblance along, and began to sing Alvin’s “Chipmunk Song.” She stuffed her fingers in her ears and turned her head away to keep from giggling. “Eddie,” she screamed, and then, dropping into a chair, she said, “You know what? I’m hungry again.”

Eddie’s cheeks were no longer sucked in. Instead, his mouth was wide open in disbelief. She took her fingers away from her ears just in time to hear him shout, “Oh, no; impossible. You can’t be hungry!” But a moment later, he was calling the hotel dining room. “I know it’s late,” she heard him say, “but it’s an emergency. My wife’s starving to death—again.”

Eddie kidded her that she’d started eating even before the plane took off from Idlewild Airport in New York. The stewardess was fixing a tray of hors d’oeuvres when Liz asked, “They look good. Could I have one?”

That’s how it started. Liz had eaten the whole tray of hors d’oeuvres, Eddie insisted. Then she’d had some tea, with champagne after. When the stewardess came round, again, with a plate of fruit tarts, Liz confessed. “I feel like Chris. I can’t make up my mind which one to choose. I like this one . . .” and she pointed to one with a little cherry on top, “. . . and this one” and she pointed to one ringed with pineapple. “Oh, I can’t decide which!”

“It’s easy,” Eddie said, “do what Chris does. Take both.”

She laughed, and she took the two pastries as if they were the most precious things in the world.

Eddie understood the real value of those tarts and all that food to Liz. Whenever she was unhappy, it was like that; she couldn’t stop eating. But he didn’t try to stop her. Instead, when the stewardess asked them for their autographs, just before the plane landed, he laughed and said to Liz, “Sign the menu. That way she’ll be sure to remember you!”

The next morning, before they’d even had time to unpack, the phone in their cottage began ringing with all sorts of invitations, but they refused them all. They said “No” to requests for interviews, pleas from photographers, phone calls from Jamaican officials asking them to dinner or to night clubs, even to an invitation from the Governor General of Jamaica. “I hope people won’t think we’re being stuck-up,” Liz said. What no one realized was that she was really very shy and that she was frightened to death by official receptions.

Instead, they spent their days, beginning at noon—because they both loved to sleep late—lying lazily side by side, alone, on the beach.

“You know what?” Eddie teased. “Your nose is shiny!” But, when she rummaged in her beachbag for a compact, he said, “No, leave it. I like it better this way. Believe it or not, you’re even prettier without makeup.” She laughed and tumbled him in the sand.

At night, they’d wear sports clothes but, to hear her laugh again, he pretended to call for her formally, as if they had a date. One time, he plucked a blossom from the garden outside and, then, knocking on the cottage door so she’d have to come and let him in, he bowed low and presented it to her.

“You’re my acting coach,” he laughed. “How was that for a bow?”

Could he have said that, laughing, back in New York? There, the matter of his acting had seemed so serious, so urgent, as if their lives together depended on it. People were saying that Liz had never had so many people flocking to see her pictures, that she had never acted so well as now. Before she married Eddie, they said, she could never have turned in the kind of mature performance she did in “Suddenly Last Summer.” But then they’d add that Eddie’s career might never recover from the blow of his marriage to Liz. “It’s like Debbie and Eddie all over again,” they said, remembering when Debbie’d had a hit record but nobody was buying Eddie’s songs.

That wasn’t the way Liz wanted it; the husband was supposed to be the important one. Nobody knew how hard she’d had to fight to get him a part in “Butterfield 8.” It wasn’t as big a part as hers—she was the star—but they’d worked hard, together, to make people notice Eddie in that picture. It was so important that he do well in it. Afterward, there was a chance of another picture they could make together, this time with a bigger part for Eddie.

So it was funny to be suddenly making a joke of it. Yet, in Jamaica, they could laugh at almost anything.

Like that first morning when they’d been having breakfast off a tray in the living room of their honeymoon cottage. There was a knock at the door and Eddie shouted, “Come in.” Four maids, armed with feather dusters and rags, marched through the door. They were followed by two porters with mops and brooms and then two bellboys who weren’t carrying anything. “I guess they’re here to supervise,” Eddie whispered. Liz smothered a giggle. And then, through the still open door, three waiters appeared to take away the breakfast tray. When they’d left, Liz leaned over and whispered to Eddie, “How many are there? Every time I count, I get a different answer.” “I’m not sure,” he laughed. “Do we count the waiters or are they just transients?” He ducked just in time, as one of the maids emptied the ashtray right from under his cigarette, and then, because they could no longer smother their laughter at the grand service, they fled to the beach.

But, when they got back to the cottage, there were still eight people sweeping, dusting— “And supervising,” Eddie added. They figured that made two and six-tenths people to clean each room. Laughing, Eddie called and had the army reduced to a more simple occupation force, leaving only two inquisitive maids and one waiter. “They mean well,” Liz explained. “They want to treat me like a queen, but, you know, I feel like a freak.” For the rest of their stay, every time even one maid showed up, they couldn’t look at each other. If they did, they’d remember the first morning’s invasion and start to laugh all over again.

They had never laughed so much together. In the scandal of their falling in love, there had been no time for ordinary courting. They had been two lovers hiding from the world. And when, after Eddie’s Nevada divorce came through and they were married and on their honeymoon, there was still no real privacy. When they could no longer hide behind the walls of the castle they’d rented in England, they emerged into a sensation-seeking, unforgiving world. Eddie had said that that first honeymoon would last for thirty years. Would it? The ugly newspaper stories . . . the people who shouted after them on the street . . . the servants in Spain who walked out on them in scorn when they found out who they were. . . . Would that last thirty years? It was better to start over, better to have a second honeymoon.

When they’d been there ten days and it was almost time to fly back home to New York, their chauffeur drove them, late one afternoon, along the ocean. Suddenly, Liz was tugging at Eddie’s arm and, almost together, they both cried, “Stop! Stop!” The driver braked the car and they climbed out. They had stopped at a lovely strip of land overgrown with lignum vitae, hibiscus, sugar cane, palms, breadfruit and scarlet royal poinciana. And straight ahead, as far as their eyes could see, was the calm, blue ocean. It was the kind of place for children to play in and grow up in; it was the kind of place where a man and woman, if they had been running, could finally stop. It was such a natural place for a house that, closing her eyes for a brief moment, Liz thought she could almost see the one they would build here.

On the following day, they bought the land. ‘‘We’ll call it ‘Liz’s Delight,’ ” Eddie announced. But Liz shook her head. “ ‘Eddie’s Eden,’ ” she insisted, and by the time they’d finished signing the necessary legal papers, Eddie had agreed.

They had needed this second honeymoon. There were days that just the two of them shared, an adventure they had in common. When they returned, the memory of it—and the promise of the house—would be something to help hold them together.

And it was really like an adventure, discovering each other. Liz found out, even more than she had previously, just how gentle and firm Eddie was. Very, very gentle, but paradoxically enough, as strong as he was kind and understanding. And he . . . he found out that she was sensitive and shy and passionate and sincere and unsure and tender. He discovered, in short, that she needed him and that he loved her.

And they talked about Mike and they both realized, more and more, that the memory of Mike Todd was always with them; yet instead of splitting them apart, Mike’s memory now seemed to bring them even closer together.

They talked about the time Mike had called a store in Las Vegas, on New Year’s Day. The store had been closed when she and Mike had stopped by it earlier. They had been walking along, window-shopping. Suddenly, she’d stopped at one window and gazed in at the display of out-of-this-world shoes. “Mike.” she’d said, squeezing his arm, “Mike, I love them.” That had been enough for him. He’d gone to a phone booth and started to make calls. It seemed he’d called everyone in the city trying to find the owner of the store.

Finally, he located the store owner at dinner with his family. And Mike talked him into coming down to open the store.

In a few minutes the storekeeper, and all his family, had hurried up in a taxi. Inside the store Mike had kept up a running commentary as Liz tried on shoe after shoe ‘Would you believe it, this doll has more than a thousand pairs of shoes? She’s queer for heels, maybe that’s why she likes me. She has the biggest collection of shoes in the whole world—Mars included! When she’s making a picture, they have a special shoe closet on the set for her, the size of an ordinary room. . . . Hey, Mrs. Schwartzkopf,” he interrupted himself, “haven’t you forgotten some? The ones in the window. The ones we came for in the first place.”

And there was the matter of Mike’s picture; the one Eddie had never showed Liz before. He himself had seen the photograph, for the first time, just after he’d opened at the Tropicanna in Las Vegas, three short months after Mike’s death. Liz. remembering the many times she and Mike, Eddie and Debbie had been together, had been there, breaking her period of mourning for her husband to be at his best friend’s opening. After the show, a photographer had brought Eddie a picture he had shot of Mike months and months before Mike was grinning into the camera, and his crossed legs revealed that he had had a hole in his shoe.

Eddie had cried when he saw the picture, and after thanking him, he’d shooed the photographer out of the room. He’d promised the photographer he’d give the photo to Liz. But somehow he could never muster up the courage to do so, the picture was so lite-like, so real. When he looked at it, he felt that Mike was actually in the room with him. He had been afraid the photograph would break Liz’s heart all over again.

But now, in Jamaica, he showed her the picture. They looked at it together, and for a moment the three of them were together again, just as they used to be. But Eddie’s eyes remained dry and Liz, though her face whitened, did not cry. . . . Their time for mourning was over, though they both knew that Mike would always be with them. He was what they had in common. Mike had brought them together and. in some strange way, kept them together. Alive, he’d expected so much from both of them and, somehow helping them grow into the kind of people he would have wanted them to, they still shared his memory. But they also had the future—and each other.

Eddie put the photograph carefully back into his wallet. Then he turned to Liz and said, “How about going back home?” She nodded her head “Yes.”

A few minutes later, with Eddie’s fingers closed firmly around hers, they walked down to the empty beach. Liz paused a moment, listening, but there were only the whispers of the waves, lapping gently against the shore. Then she said, “It’ll be good to get home, won’t it?”

THE END

LIZ STARS IN “SUDDENLY, LAST SUMMER” FOR COL. SHE’LL BE SEEN WITH EDDIE IN M-G-M’S “BUTTERFIELD 8” EDDIE RECORDS FOR RAMROD.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

AUDIO BOOK