Inherited–A World Of Love—Kirk Douglas

Peter Vincent Douglas may not sound like a girl’s name to most people—particularly when this name belongs to a red-headed baby boy born the twenty-third of last November. Nor does such a name sound as though the little boy had been named for his mother, whose given name is Anne. Yet he is.

Furthermore, with a solid English-type surname like Douglas, it seems rather amazing that, eating his Pablum, on the luxurious sunporch of a brand-new house in Palm Springs, California, small Pete is actually the result of the dreams of a French grandfather and a Russian grandmother.

Sound crazy? Only as crazy as love often is at its most enchanting. Crazy as dreams usually are, particularly when they do come true. Crazy as Pete’s father’s gifted talents, and the opportunities that our land gives to all people who are courageous, persistent and utterly determined to grow.

For certainly. thirty years ago, in Amsterdam, New York, almost no one, looking at small Issur Danielovitch standing in his mother’s kitchen—while that heroic woman tried to divide one egg and four slices of bread between him and six daughters, for their big meal of the day—would have predicted that in 1956, he would be the celebrity, Kirk Douglas.

Even three years ago, Kirk himself would never have predicted that on May 29, 1954, he’d be standing beside Anne Buydens in Las Vegas while she, with an innocent error in English, promised “to take, thee, Kirk, as my awful wedding husband.”

Kirk had been utterly disillusioned about everything when he met Anne Buydens in France, where he had gone to make “Act of Love” in 1953. Life in Hollywood, liberty from marriage, the pursuit of happiness among the most beautiful women in the world had brought him only boredom. He had sold his Hollywood house. He said of himself then, “I have no roots.” He had gone to Europe to make three pictures, and to try to find the something he felt was missing in his life.

Today, with the house in Palm Springs, and another in Bel-Air, with small Pete asleep on the sunporch, with the great success of “Ulysses” and “Indian Fighter” in the theatres, and Anne beside him, he’s completely relaxed. He says, “Anne has taught me the secret of happiness, which is that you can only achieve it by thinking of the other person first.”

Now, basically, Kirk is a man of dignity, so it isn’t easy for him to speak of love. On the surface, he’s all dash and charm. Constant study has taught him everything from several languages to refined diction and how to handle a fish fork. Put him in a drawing room, and he can out-talk anyone in Hollywood—except Burt Lancaster, who can out-talk anyone, anywhere. At a party, Kirk turns into the type of male charmer who casts a glittering, gay eye on all the ladies present. And, in general, he does all the things a successful, delightful gentleman is supposed to do—drives fast, expensive cars, appreciates fine food, swims wonderfully, dances like a dream.

But it’s all an act. Underneath, he is still small Issur Danielovitch braced against the cruelties almost all poverty-stricken little boys experience when they move about in an American city.

Or, at least Kirk still was basically Issur Danielovitch, until he met Anne Buydens, who was braced against even being interested in him because he was an actor. Actors were her job. She was a European publicity girl and the immediate job she was hired for when she met Kirk was getting good notices in the papers regarding “Act of Love,” in which Kirk was the star.

Being a smart publicity girl, Anne boned up on her client long before she met him. She immediately discovered that Kirk had been married and was divorced, as was her own case. She found out, too, that there was.a girl in his life, Pier Angeli. She saw that there had been other girls in his life before Pier, since his divorce. She determined she was not going to be- come another of them.

“Of all places in the world,” Kirk told me, giving his wife a rueful grin, “I first discovered I was falling in love with Anne when I was in Havana—when she was half the world away from me. I had come back from making ‘Act of Love’ and I had to stop in Havana for business. I thought of Anne then as the most wonderful friend I’d ever known. Now that I look back on it, I realize I’d never had a woman friend, with the exception of those old enough to be my schoolteachers. I should have known that with anyone as pretty and alert as Anne I was not really interested in her fine mind—exclusively, that is. But to be truthful, I didn’t even think about that because she seemed to be so interested in my mind.”

“I was,” Anne interrupted. “I still am.”

“One thing Anne was interested in,” Kirk said, “was in being helpful. She always is. When she knew I was going to Havana, she gave me the name of a friend of hers there, told me to call him if I needed any assistance, or was merely lonely. So I was merely lonely in Havana and I did call him. I introduced myself to him by phone. ‘This is Kirk Douglas,’ I said. He said, ‘Oh?’ I said, ‘I’m a friend of Anne Buydens.’ He said, ‘Anne Buydens! Well, why didn’t you say so? Will you come for lunch? Will you come for dinner? Is there anything I can do for you?’ In other words, I meant nothing as myself—but as Anne’s friend, I rated. It was Anne who was the personality, not I.”

Kirk paused, then said thoughtfully, “I keep finding that out more and more about Anne. The reason she was a personality was because she was genuine. For instance, I don’t think any man really means to develop a line. But when you are ‘unattached’ as the saying goes, you find that you have. You meet a strange girl at a party. You don’t know what interests her so you say, ‘I can see that you’ve had one love affair that hurt you deeply’—and immediately you are listening to the story of her life.

“But not Anne. I said to her the first time we met, ‘I can see that you have had one love affair that hurt you deeply.’ She answered, ‘Who hasn’t?’ and proceeded to talk about me and the picture. Or I’d come back to my hotel, after the day’s shooting, and find a list typed out by her, thoughtful stuff about where I might eat, or the like. Or I’d phone to thank her and her line would be busy. She’d be on the phone, wishing about six people happy birthdays, or arranging anniversary presents for another six, or commencement presents or some such. She must have a hundred people whose birthdays she never forgets, and the human interest stories she can tell are fabulous.

“More and more, on the set of ‘Act of Love,’ I found myself talking to this unusual press agent, not with phony smoothness, but philosophically. Because I wanted to perfect my French, Anne talked only in French to me. I discovered myself telling her things I had never told anybody, not even myself—dreams I’d had, dreams I still had, hopes and fears. Every once in a while I’d say, ‘Have you ever thought about going to Istanbul, or Alexandria?’—or whatever, and almost inevitably Anne would say, ‘Oh, I was there once.’ I swear, one of the reasons we were married at Las Vegas was that that was one of the few places that Anne had not been ‘once.’ ”

When Kirk finished “Act of Love,” he went to Italy for a vacation and to prepare for his next picture. He found he hated to leave his friend, Anne Buydens. But Anne was glad to see him go. She hoped she would never see him again, for she knew that she was in love with him. She could not, first of all, permit herself to be in love with the actor, and what was worse, in love with the actor who was in love with someone else.

During the next few months, Anne worked hard, played hard. Extremely popular, she had no lonely evenings. The winter passed and spring came and the chestnut trees along the Champs Elysées were in bloom when her firm told her they were sending her to Rome to handle a picture called “Ulysses.” The assignment would probably take six months. It was a wonderful opportunity for an ambitious young woman. The star of the picture was Kirk Douglas.

“I had to make up my mind whether I wanted to lose my job or act absolutely impersonally toward Kirk,” Anne recalled.

“She acted absolutely impersonally about me,” Kirk said, “except when it came to violets.”

In spring, in Rome, they bring the violets down from Parma, and they are incredibly beautiful, incredibly sweet- smelling. Kirk, working very intensely, didn’t even know about them, as he talked to his wonderful friend, Anne Buydens. In Rome, they talked Italian together because he wanted to perfect that language, too, and Anne went with him to see the Vatican—where she had been before some half a hundred times—and the ancient churches, the ancient roads, the new, fashionable shops.

Pier Angeli had long since gone back to America, and Kirk, completely wrapped up in his work, would often find it was evening before he thought about his dinner date. When he’d call Anne, he’d find her already engaged. One day he said, “Oh, I know it is the last moment, but. . . .” He didn’t tell her that in Hollywood he’d done it a hundred times and never had to be lonely.

But Anne said, “Did you ever think how it would seem to any woman if you thought about her first? First thing in the morning? About taking her out that evening? And perhaps in the afternoon, you sent her a little bunch of violets to remind her of the date?”

That shocked Kirk in a way that a price for a motor car, let’s say, would never have done. The beauties of Hollywood will often give the most casual male acquaintance something like emerald cuff links, or they’ll accept a mink coat. But for a girl to want violets—just for the sentiment of it, to prove she was thought of, not on impulse, but sweetly! Behind the smooth facade of Kirk Douglas—who had told the world, “Whatever there is, in life, I want a lot of”—little Issur Danielovitch, who had been so grateful for the smallest kindness, came back into idealistic awareness.

To send violets in Rome, Kirk soon discovered, was not like sending them in Hollywood. You couldn’t just phone for them. You couldn’t just go to a store and buy them. You had to prowl the streets until you found a flower seller, who twisted the bunch of them, which cost less than five cents American, into a bit of tissue paper, all the while inquiring about your health, your happiness and the love of your children.

Yet it was a singularly rewarding thing to do. It brought to Kirk Douglas a sense of the simplest happiness, to walk down a leafy Roman street, see some trifle that suggested Anne’s eyes or her laughter or her quick intelligence, buy it, and take it to her. It was like the evenings they began to share more and more often, at the open air tables along the Via Veneto, mostly drinking the sweet, light Italian vermouth and eating nothing more involved than cheese and fruit—but which, somehow or other, tasted better to him than Romanoff’s most deluxe dinners. And more and more, Kirk was calling Anne “Peter,” sometimes “Pat,” because he had learned from her that her father had wanted her to be a boy, had even named her Peter, but of course, outside the house, nobody in France would ever think of calling a girl by such a name.

“Ulysses” took eight months to finish. Kirk knew that he must part from the best friend he’d ever had. Anne knew that she was more in love than she had been with him in Paris, but she was even more determined that Kirk should never know it.

Then, a few months later, fate stepped in again, and Anne’s publicity firm suggested she go to America with Mr. Douglas, to tie up a few of the odds and ends on the production.

“I came on the shortest possible visitor’s visa,” Anne recalled. “It meant I could stay in Hollywood a very few weeks. I was so glad. I could not have lived through being discarded, knowingly, by Kirk. Day after day, I’d tell myself I’d be leaving soon, and nobody but I would be the wiser.”

Nor was Kirk the wiser until almost the very day Anne’s visa was due to expire and she told him she was to leave. Then he found himself suddenly proposing, suddenly proclaiming that she must elope with him at once, to Las Vegas, that day, that instant. Almost at once, he had his lawyer and his lawyer’s wife, his press agent and his press agent’s wife at his house. In another hour or so, they were headed for Las Vegas.

Anne Buydens Douglas can still scarcely believe any of it. “A girl expects her wedding to be a little solemn,” she says. Instead, upon landing in Las Vegas, she found herself being rushed to the city hall. There is one hour of the day in Las Vegas—and one only—when you can’t get a marriage license, and their plane landed ten minutes before that hour.

They did turn out to be too late, so somebody proposed they just drop into a gambling casino to kill the waiting hour. “I did not know till then,” said Anne, “that my husband-to-be was mad for gambling.” Also, accustomed to the elegant casinos of Monte Carlo and such, she knew nothing about a place like Las Vegas where the “one-armed bandits” are even placed in washrooms.

So the Douglas bridal party lost money for an hour and then were hustled through the back door of one of Vegas’ swankiest hotels and up to the bridal suite. A tall man, in cowboy boots, stood before the bride. He was, it seemed, “Honest John Lytell” and with his Texas drawl and Anne’s limited English, she couldn’t understand a word he said. That was why, when he told her to repeat after him, she did promise to take this man, Kirk, as her “awful wedding husband.” And it was hours before she knew what all the wedding party were laughing about.

It was hours because they all went back for some more gambling. All except Anne. They didn’t even notice that she did what she always does—she was helpful. She soon learned how to cash in their chips or get them more money. Hour after hour went by, until finally Anne pulled at Kirk’s sleeve and said, “Darling, I really must go to sleep.”

He kissed her, not taking his eyes off the spinning roulette wheel. “You go. I’ll be right there in a minute.”

The minute lasted two hours. Then the whole party walked into the bridal suite and cried, “Look, we’ve brought hors d’oeuvres and drinks.” So of course they ate them, and then somebody else cried, “Look. The sun is up,” and somebody else said, “Let’s go downtown and try our luck at the other places.”

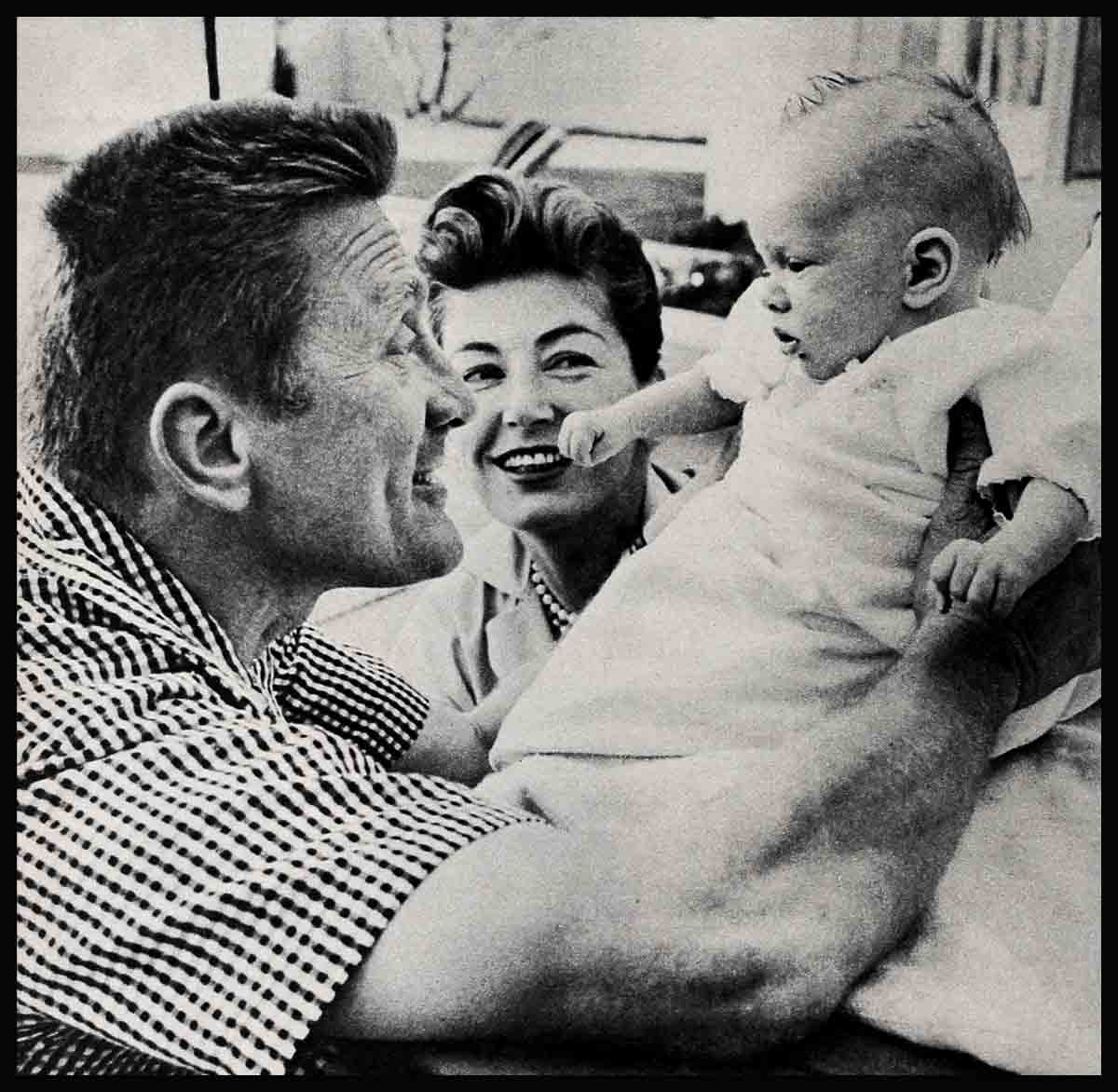

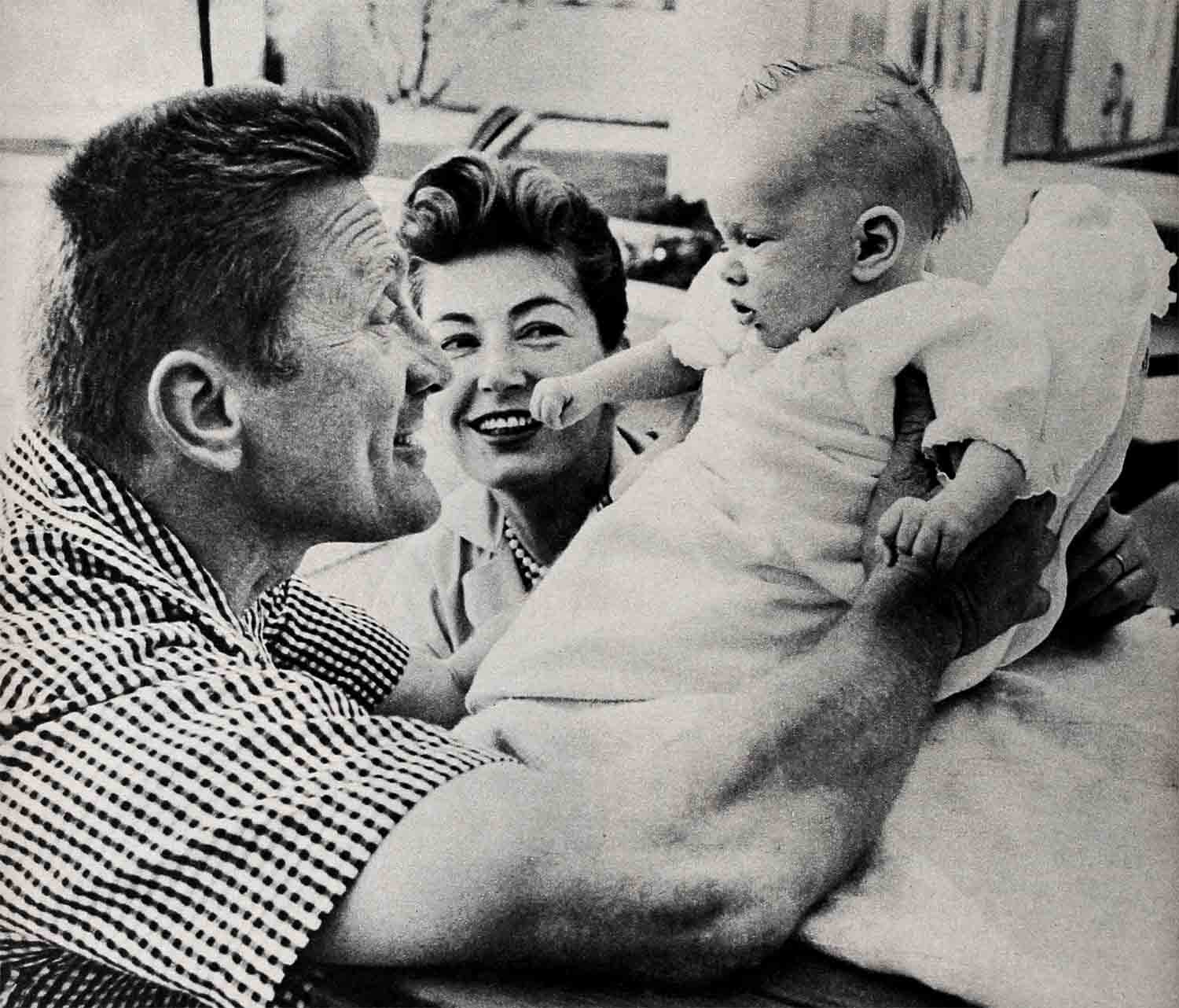

As Anne told this story in Palm Springs, Kirk lay stretched out on a couch watching her, his eyes alight with amusement and admiration. “When I came out of that gambling coma,” he said, “I knew what a terrible thing I’d done to Anne. And then I realized my tremendous fortune in ever meeting such a girl. Even an impossible situation like that, she could let me be myself. Which meant that with her, and through her with other people, I didn’t have to keep proving myself all the time.

“A few months later—when the Russians used me as propaganda, saying I didn’t know who Homer, the author of ‘Ulysses,’ was—it meant that I could throw the lie back in their teeth and do a propaganda job for our country, showing the opportunities a poor boy such as myself had been given.

“This,” Kirk continued after a slight pause, “is what is meant by growing up, I’m sure. Not throwing your weight around, not exploding in anger, not pulling a line. And with Anne it’s going to be a case of my keeping up with her. This morning she wanted to go out bicycle riding. I haven’t ridden a bicycle in years, but I was sure I could beat her, who had just had a baby. So look at her after an hour of it. She’s as fresh as a new moon, and I’m beat.”

At that instant, Peter Vincent gave a yell. “Feeding time,” said his father.

Anne rose. “The first time a woman hears her first baby cry she grows up and knows what life is all about.”

“Tell us,” said Kirk, grinning at her.

She grinned back, as she put the baby over her shoulder to take him away. “Merely love,” she said.

Kirk leaned over to me and said in a stage whisper that he knew Anne could hear, “He’s Peter, meaning Anne, and if we have a girl, she’ll be Anne meaning Anne also. But if I am very thoughtful and careful, I may be able to keep my wife from discovering that this baby is not necessarily the baby who is going to save the whole world . . . or is he?”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956