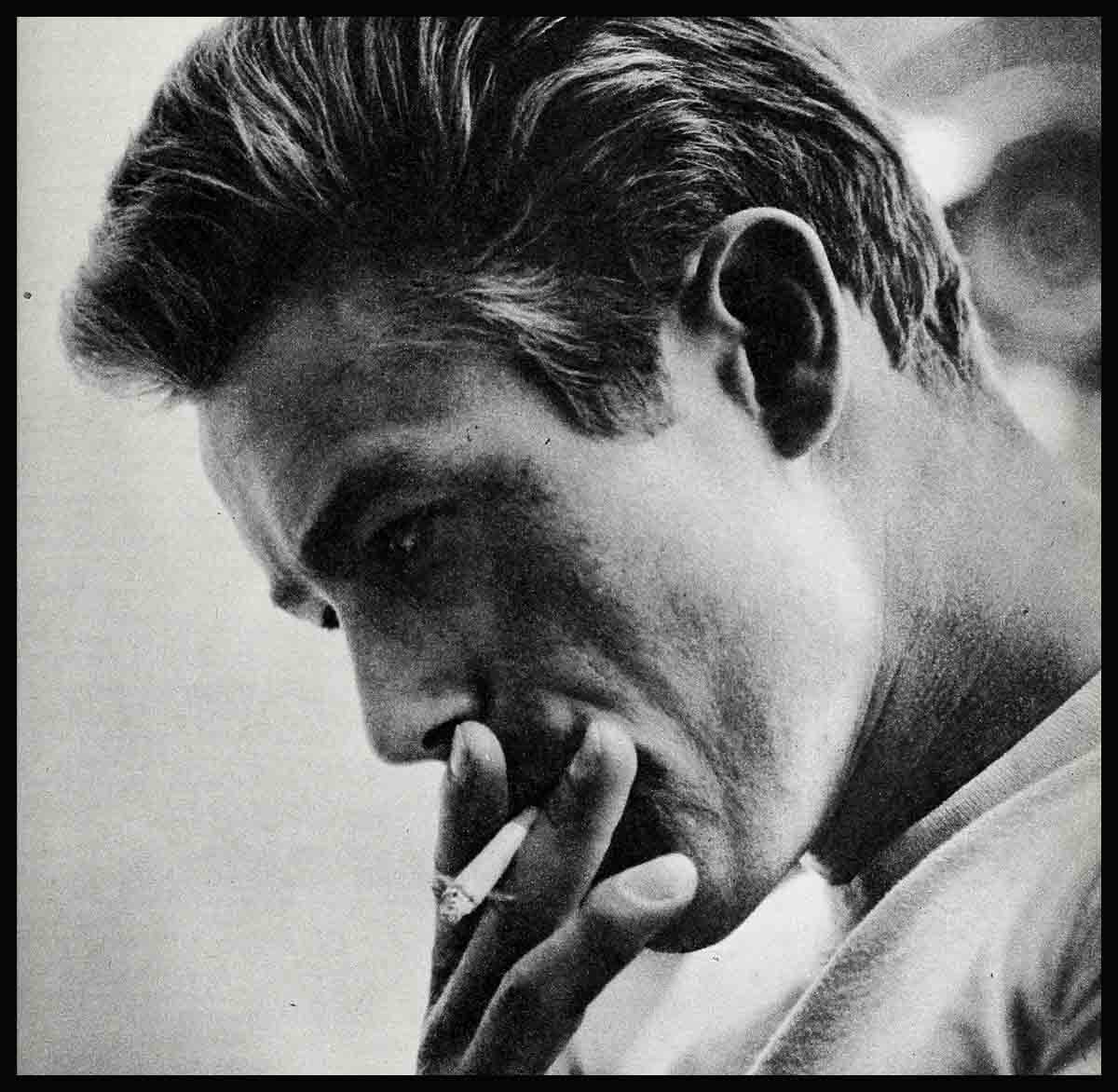

In Memory Of James Dean

She was a struggling dancer. He was a lonely actor. Together in the cold, hard city of New York they loved, and laughed and dreamed. This is Elizabeth Sheridan’s own story:

The first time I ever knew that Jimmy Dean existed was one afternoon at the Rehearsal Club in New York. It was raining. He was sitting in the living room, and I heard him ask a lot of other girls if he could borrow an umbrella, and nobody seemed particularly interested in whether he got wet or not. So I loaned him mine and he was overly grateful. A couple of days later, he came back and returned it. One of the biggest interests that he had at the time was bullfighting. He caught my interest because I was also interested in bullfighting. That, I think, was the important reason we got together at the very beginning.

Then, I was dancing in a trio, two boys and me, and we were rehearsing about two or three blocks away, and one night these two guys came to the Rehearsal Club for a rehearsal that we were going to have, and Jimmy asked if he could come along and watch. So he did, and he was very much impressed by the whole thing. We had a habit of stopping in this place—a little neighborhood joint—to have something to eat before we went home, and Jimmy came along with us.

I remember it was a very funny incident. We liked a certain kind of beer that was out at the time called Champale. It seemed it was somebody’s birthday, but I can’t remember whose it was, and Jimmy was, more or less, my date. The waiter, when I ordered Champale, thought I said champagne, and he came back and he brought a bottle of champagne and Jimmy’s eyes almost popped out, because at that time he was living at the “Y” and he didn’t have a cent, and he was borrowing from everyone in town and, instead of saying, “You made a mistake of some kind,” he said, “Oh no, I can pay for it.” He made a big thing about that. It was funny.

My two dancing partners and So Height were there, too, I think. Everybody used to meet at this place. Jimmy didn’t impress me one bit when I first met him. I thought he was a little straggly kid that somebody had brought in—actually that’s more or less what happened. One of the girls took a liking to him at a TV rehearsal and brought him there to give him a good meal because he looked hungry, he looked lonely, he looked like he needed a friend. Actually, years later, I found out that he always looked that way. And up until the rehearsal night, he didn’t one way or the other impress me.

A couple of nights later, I remember, I was sitting in the living room of the Rehearsal Club and Jimmy was there, too. Boys were allowed to visit the girls up until 11:00 or 12:00 P.M. I forget what time it was and there were two couches, one facing the other. I was sitting in one and Jimmy was sitting in the other. And I was reading a magazine and he was reading a magazine, too. I quoted something out of the one I was reading and his answer was a quote out of the magazine that he was reading and we carried on a conversation like this for about fifteen minutes—you know, real fun—and we both got a kick out of it. Suddenly, he said, “I have an idea. Would you like to go up to Tony’s, the place that they have this Champale?” And I said, “All right. What the heck!”

So we went around there and we sat down in a booth and a couple of kids that both of us knew were in the next booth and we got into a conversation and his ideas and my ideas sort of jelled and he became interested and so did I.

Then we started drawing pictures on a napkin, I remember, and I was very much impressed about the way he could draw. Jimmy was sort of self-taught in almost everything he did. He was a very good artist, so I started to draw the only thing I knew how to draw—a tree. And he remarked how good it was and we just seemed to be getting to know one another closer and closer all the time. I think he was more impressed than I was at first.

A couple of nights later I had a costume-fitting somewhere up in the Bronx, and Jimmy said he would meet me at a little place around the corner. He was just sitting around the Rehearsal Club and I didn’t take him too seriously. When I finished this costume-fitting and I was going by this place—Tony’s—instead of going straight home, I went in just to see if Jimmy was there. And he was and it turned out to be his birthday and he started saying all sorts of things about that was the best birthday he had had in years.

When I first met him he drank beer, but after I got to know him very well, he really didn’t take to drinking much.

Then we started going around together quite steadily. He used to call me at night or in the daytime—any time he happened to feel like it. He’d play records for me over the telephone. We would sit and talk for hours and hours and it was a desperate kind of feeling he had towards seeing me any time that he had a spare moment and talking to me any time he had a spare moment, almost like he didn’t have anybody else, either. He just sort of hung on and, I guess, I must have been particularly lonely at the time, too, because we got to be inseparable.

One thing that was quite remarkable about him was that he never for one instant thought that he really couldn’t make it. I mean he always knew that he would one day be a star, and there was no question in his mind about it at all. He was interested in the stage. Well, actually he was just interested in acting.

He got a couple of television parts during the first year that we were together in New York. In one of the first ones he played a soldier that was up for court martial and, I think, hanging or something like that. He was supposed to die and he was called in to see the President and it was a very dramatic scene. He didn’t have too big a part, though. He always insisted that I come to his rehearsals, and he always wanted me to come to his performance and sit in the back and wait for him until he got finished, and then he would always want to hear my criticism on how he did. He seemed so sort of insecure in his acting and yet he must have thought he was good because he had no doubts about getting to the top.

Well, after this went on for a month he would call me and I would see him almost every night. We would either go around the corner for a beer, or just sit in the Rehearsal Club and talk, or meet on the street, or I would go and watch one of his shows, or we would sit in an automat until late at night talking about scripts or trees or grass or bugs or anything.

He told me he did a lot of sketches and stuff and put them up on the wall at his place. He spent a lot of time teaching me how to draw. He got about one or two television shows and I, in the meantime, was working on Mitch Miller to do something about my singing which was lousy. Jimmy was very firm about my singing. He never really thought that it was too good. He wanted me to continue dancing, although the auditions didn’t turn out very well.

Then we went through a period where he couldn’t get work and I couldn’t get work, so I went to American Photograph Corporation and started working there as a retoucher. We used to eat together. We ate Shredded Wheat. We bought a lot of sugar and a lot of milk and we ate Shredded Wheat, sugar, and milk for dinner at my place lots of times. I had this little card table that we would set up with candlelight and make a big thing about our dinner of Shredded Wheat, sugar and milk.

We both lived right near Central Park so we used to walk there in the evenings a lot and sit on the rocks in the park and talk and during the day, if he had it free and if I had it free, we used to practice bullfighting. I would be the bull and he had a cape which was given to him by Sidney Franklin. It still had some blood on it. I remember him talking about it.

Then I made a record for Columbia with Mitch and I remember the day Jimmy and I went all over town looking for a place where we could play it. We found this record store and we went in and we listened to my record a couple of times and we criticized it to the end and he said, “I think you should dance.”

Then we really got in pretty bad condition because neither one of us had any money and I remember I quit American Photograph and he came over that night and we had fights about that and I said well all my time was going to American Photograph and I didn’t have any time to spend on following any sort of a career. He got mad and walked out.

Fifteen minutes later the telephone rang and I went downstairs and it was Jimmy and he said couldn’t we please go around together again. He was so unhappy and I was, too, and we made a date to meet in Columbus Circle under the pigeons and we were going to go to a movie. I went up to meet him and he was sitting there. He looked as if he’d been there for hours waiting and it seemed like our first date. We were both so miserable about being poor and not getting anywhere that it was most exciting and one of the best dates that I had with Jimmy.

We went to a movie on Forty-second Street and held hands the entire time and then instead of going back to the “Y” he came over for a while. I lived in a tiny little place off Eighth Avenue and if there were two people in it it was crowded. And Jimmy and I figured out how we were going to give a party together. We wanted to give a big party, inviting all sorts of commentators and theater critics and stars.

Then I got a job with my girl friend Sue’s boyfriend to start as assistant choreographer and it was in New Jersey (Ocean City), so I went down there. Jimmy was living in the Iroquois Hotel with his friend Bill Bast, and I was down there about a month, I guess, and he came down. I went up to New York for a visit to see him and talked him into coming back down with me for two or three days. He came down and he seemed pretty unhappy.

He was around a lot of stock people. He was around the theater and everything, but he wasn’t doing anything and I think he was kind of depressed and in a hurry to get back to work. He went back to the city and after that I heard that he was going to go on a cruise with his producer, who was doing the play “See the Jaguar.”

With the end of the summer, I went back to New York and I didn’t have any place to stay. Jimmy had made arrangements for me to stay with this friend of mine, Anne Chisholm. In the meantime, he was out sailing somewhere off the Cape. For some strange reason or other I was on a bus one night. I didn’t know when he was due back in the city, and I was just passing on the bus the place that we first had a couple of drinks, the place that was right around the corner from the Rehearsal Club. All of a sudden I saw him walking down the street going towards Tony’s Bar. I leaped off the bus and I saw him turn into this bar and I went in after him. When I got there he was in a telephone booth trying to locate me, and I rapped on the door of the telephone booth, and I had never seen him more shocked. We had a great big mad love scene right in the middle of the floor.

Then I got a job working in the Paris Theater as an usherette. That was when we decided to take this trip to Indiana. We were going to hitchhike all the way. To me it seemed like a wonderful escapade, so we induced Bill Bast to come with us and we started out of the city. I remember we went to New Jersey by bus through the tunnel, got off at the other side, and started thumbing on the highway there.

We got a ride through half a state, I think, and we made Indiana in three rides. The last ride we got was with a very, very famous baseball player. He was catcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but since then he has been sold, and I don’t remember what club he has been sold to. He was very worried about the three of us. He didn’t know exactly what we were doing on the road hitchhiking, and he knew we didn’t have much money.

I remember he had a Nash Rambler. It was very comfortable and most of the time Bill sat in the front seat and Jimmy and I huddled in the back because it was freezing cold. We would sing songs and then we would ask him all about baseball players and what they were like, and Jimmy didn’t say too much all the way out. We all seemed to be having very much fun.

He left us in Indiana at a crossroads where we could telephone Mark, who was Jimmy’s uncle. And just before we left, this baseball player took Bill aside (we found out later) and offered him some money for us, to take care of the three of us, and Bill refused and he said if ever we were all in New York some time we could get together. I think it was the next season we were supposed to meet him at the Roosevelt Hotel, where the ball players stayed, and he was going to take us out on the town and treat us to a time.

And then we called Jimmy’s family and Uncle Mark came and called for us, and we spent a perfectly glorious week on his farm in Indiana. We were up about seven or eight o’clock in the morning. We were out shooting things. We would throw tin cans up in the air and practice shooting, and we went horseback riding and we visited Jimmy’s school, his old teachers, and we sat in on the rehearsal of a high-school play and Jimmy coached.

We visited Jim’s grandmother and grandfather. We met his father, who came all the way from California. He is a wonderful man, a dental technician and while he was out there, he gave Jimmy two new front teeth—they were coming loose because he had his teeth knocked out in football when he was a kid.

Then just about the end of the week Jimmy got a telephone call from New York saying that he got the part in “See the Jaguar.” so we had to hurry back. We started out on the highway again going back to New York and we got a ride all the way back to New York with this man who owns oil in Texas. A very rich guy. He had ulcers. He said he couldn’t eat anything and every time we would stop and get something to eat, he would go out and get violently ill by the car and then we would start off again.

On the ride back into New York, all of us were very, very depressed, as I remember, especially going into New York through the tunnel, because we didn’t want to get back into the city. Even Jimmy didn’t want to get back into the city, because we were having so much fun in Indiana and it was the freshest air the three of us had smelled in a long time.

Then it all started. He got swept up in the theater. He went out on the road, I think to Boston with “See the Jaguar.” I didn’t hear from him for about a month. Then one night he called and said he was back in the city, and that they were opening in two nights and he came down to see me at the Paris Theater where I got my old job back as an usherette.

One night I was working at the Paris Theater and he came with his friend Bill Bast and Bill’s friend Tony. We all went out and celebrated because he got the part in “See the Jaguar.” That was one of the last fun times that I ever had with Jimmy because after he got into the play, I didn’t see much of him. As a matter of fact, he sort of disappeared after opening night. He seemed completely different once he got involved with “See the Jaguar” and Arthur Kennedy.

We sat in a neighborhood joint the night that he came back, after I had finished work, and he seemed to have something really bothering him, and I asked him what it was. The way he talked it was so hard and his gestures and everything were hard and sort of I-don’t-give-a-damn kind of thing. He wasn’t warm at all the way he used to be when we first went around.

But he wasn’t always this way. I remember one time he went out for groceries or something and while in the grocery store he called me on the telephone. I don’t know what had happened from the time he left until the time he got to the grocery store, but when he called he said he didn’t have anything really to call about except that he wanted to get married, and he said, “we must get married before we get caught up in all this.”

I remember him saying that, and he came back and that was one night when he seemed like he was afraid. There were lots of times when I felt that he was afraid. The way he hung on to me at the very beginning. After he got established, then I was afraid and I started to hang on to him, and he didn’t seem to want the responsibility of having anybody hang on to him because he was going up too fast. That was just extra added weight.

What happened to Jimmy after that I don’t know. In the first period of work in New York when he started getting up there he started getting television shows maybe once a month, which was a lot for him at the time. He had a lousy attitude about working. It seemed like he didn’t care about rehearsals. He didn’t care about the way he dressed. Sometimes he didn’t even care about whether he was decent to people or not, as long as he was acting. He felt the business of show business was degrading.

The change. I wish everybody could have been with us in Indiana. The way he treated the animals. The way he treated even the dirt around the farm. Sort of the love he had for nature and everything showed me how completely simple he was. Simple in his ideals. Whether he was sure of what they were or not I am not sure, but he had them. They were growing But it made him pretty bitter, and he seemed to relax much more when we were out in Indiana.

One of the biggest things about him that I can remember is his love for animals. The way he could get so close to them, and animals get close to him. This, to me, is quite a key to somebody’s character.

After “See the Jaguar,” he disappeared I found out he moved back into the Iroquois Hotel after Boston, and it took me about two months to find him. When I did, I called him one night and I went over to see him. He was living in this little hotel room, and he seemed in even a worse condition than he was when he was so hard and bitter about New York business, and the guff that you have to take with the theater in trying to get somewhere. He was studying Greek philosophy and reading Roman history and was studying music.

Howard Wilder was an interesting person and so he took up with Howard Wilder. He would hang on to anybody. Anybody that he felt he could get something out of—not money-wise or material-wise. He felt that any knowledge he could gain from anybody was valuable. As a matter of fact his time was valuable. He seemed to be in a hurry about something. I don’t know what. Maybe a feeling that he wasn’t going to live very long. I don’t know.

Even though many of the articles that I have read about him say that Jimmy was well educated, I don’t think so. He didn’t have as much schooling as he had wanted and he tried to catch up with it all the time. He taught himself how to paint. He taught himself many things.

One thing he always kept telling me all the time even in his letters to me when I was in stock is that a person must know the field that he is going into. You have to know your art. This is something that he stressed all the time.

He liked steaks. He liked good steaks. He was always talking about steaks but in the early part of our friendship we didn’t do much eating, and he didn’t take too much notice of what he was eating when he ordered. He made up real crazy dishes when he was living in the hotel, and I used to come and eat with him because neither of us had much money and we had to concoct things other than Shredded Wheat.

That was when we really ran out of money. Before that first part we used to buy canned meats and make hashes and stuff. Clothes Jimmy never cared about. He didn’t take care of his clothes very well, either. He would send them to the cleaners and maybe sometimes he would forget about them and I would have to get them out for him. He liked blue jeans. He lived in blue jeans most of the time. as everybody knows, and T-shirts. He had an old lousy camel-hair coat that some girl had given him when I first met him and felt sorry for him. And he had a raincoat which I always had my eye on. I just adored that raincoat. It was three-quarter length. I made a deal with him that he could have my blue jeans if I could have his raincoat. And he finally gave it to me and I still have it. That and a picture are about the only two things that I can remember keeping.

Lots of times we used to walk along Fifth Avenue and look in the store windows. Mostly it was cars. He was fascinated by cars. He always wanted a Jaguar and I always wanted a Jaguar and there was a place on Broadway up around the Sixties, a great big store window that had all sorts of cars in it. We used to hang around and look in the window and dream about the Jaguar we were some day going to get. It turned out he got a Porsche or it got him.

My roommate and I had a great Dane, a beautiful dog. I used to take him for walks in Central Park. I remember I called Jimmy one afternoon and told him that maybe he would like to see our dog that we had just acquired, and I would be in Central Park at such and such a time and at such and such a place. So I remember I was playing with the dog in this great big field and I saw Jimmy and we must have spent a good hour there just running with the dog and throwing things for him, and having him run and bring it back to us and this is one of the few times that I saw him laugh during the last days that I ever saw him.

Two years ago, after I lived in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, I came back to New York and my first dancing partner, Fobiel, heard I was home and called me. He said he met Jimmy on the street and had a conversation with him, and told him that I was in New York and where I was. Within an hour Jimmy called me. I was over at a friend’s house and we were going to have a party, and on the phone, it was the strangest feeling I got. I could almost visualize Jimmy doing flips and stuff while he was talking to me, because it seemed like I didn’t know he had such a wonderful life out in Hollywood and so many things had happened to him. I thought he would be so terribly happy but he didn’t seem to like it at all.

He seemed like he would rather be around his old friends, and he seemed like he was glad to hear from me and went on and on about how he missed me and how much he was thinking about me, and one of the first things he said was he got a horse. He always knew that I loved horses. And this gave him a large charge. Every time he would see a horse he would go blocks out of his way to point it out to me, or pet one down around Fifth and Fifty-ninth Street, where they all park.

He wanted to know immediately where I was and if he could come up, and I said we were having a party and he said he was with Jane Dacey, his agent, and Leonard Rossman, who had written the score for “East of Eden.” They were going out to get some dinner and could they come up so I said sure. So about an hour later he called from Sardi’s and said that they were eating dinner and he had forgotten the address. What was it again?

They came up and it was a wonderful homecoming, and he was happy to the point of almost hysteria. He was leaping and jumping all around like a clown, which he did very often when he was happy and I remember wherever I went at that party—if I would go into the kitchen to get food—he would follow me out there and stand and talk. Never anything about Hollywood or what he was doing but what I was doing, or how was the old gang. It seemed that he had just been away from home, and all of a sudden he found it again and he seemed jovial on top—but very unhappy underneath, somehow.

We left together. I remember he asked me what I was going to do. If I was going to go home. I said I didn’t quite know, and he acted like he wanted to at least have a drink or talk a little bit more before I took the train for Larchmont, but Leonard Rossman talked him out of it and talked him into going to another party. So the three of us took a cab together and I got off at Grand Central. I remember, just before I left, he squeezed my hand in the cab and asked me if I were happy. I told him that I would be as soon as I could get back to the islands and he said, “I know what you mean,” as if more or less he wished that he had found a place to go to where he could be happy. Then he said, “Now that I am more or less established and can help you, I wish you would come out to Hollywood, and I’ll see if I can get you some dancing.” He was the greatest enthusiast that I had about my dancing. He thought I was the living end. And that’s the last I saw of Jimmy.

When I heard about Jimmy’s death, I was sitting in a movie house in Puerto Rico, where I live now, and I heard a newsboy shout out in the streets that James Dean had been killed in a sports car accident. A lot of thoughts raced through my mind, mostly what I’ve been telling you about. About the desperate feeling he always had in wanting to see me any time, anywhere . . . about his fascination for cars and how he always wanted a Jaguar. But how he didn’t like to drive and always made me do it.

I may forget a lot of other people, but no matter what happens, I’ll never forget Jimmy Dean.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957