Grace Kelly: “Please God, Don’t Let My Father See Me Cry”

She took a deep breath, like a tremendous sigh. And when she raised her head, the worry was erased from her face. She was ready for her father. When she’d walk through this door into his room, she would need her skill in acting more than ever before. She would have to smile, though her heart was heavy because she mustn’t let her father see her cry.

Suddenly, startling her, the door opened and a nurse intercepted her.

“I’m sorry to make you wait,” she said softly, “but the doctor is with your father.” She hesitated a fraction of a second, as if not sure whether she ought to say “Your Highness” or not. Then, as she saw the anxious look on Grace’s face, the nurse smiled kindly and tried her best to sound reassuring. “It’s just that it may take ten or fifteen minutes longer,” she said. “Why don’t you sit down?” She indicated a chair in the corridor not too far away. “I’ll come for you when you can see him.” She went back into the room, quietly shutting the door behind her.

AUDIO BOOK

Princess Grace sat on the straight-backed wooden chair, not noticing just how straight or how hard it really was, almost grateful in a way, for a few moments alone. A door was shut between her father and herself. She had no way of knowing what was happening behind it. She could only try to imagine how her father looked lying there against the white sheets. Was the doctor’s face grave as he bent over him? Did the door look so forbidding, so frightening only because it was closed against her? Or had her father taken a turn for the worse and was the nurse hiding it from her?

Two white-coated attendants passed by, pushing an empty stretcher cart. They recognized her but, then, as if respecting the grief and worry they knew she must be feeling, they turned their heads away.

Far down the corridor, on the floor nurse’s desk, a phone rang shrilly. Just as, only a few short days before, her own telephone had rung in the palace at Monaco.

All day, she had waited tensely for the overseas call from her mother to tell her the operation was over—and to say how it went. It was dusk already, and shadows lay on the palace courtyard, on the bright gardens overlooking the blue sea. But, in Philadelphia, it was only early afternoon and it was strange to remember that, in America, the day was a holiday—Memorial Day.

When the phone rang, she picked it up quickly, cutting it off at the first shrill ring. She gripped the receiver tightly as she listened to her mother’s voice sounding tired, yet relieved. It had gone very well . . . yes, it had been what the doctor thought, adhesions from last year’s emergency operation . . . Dad’s condition was good . . . No, there was nothing to worry about.

Brave, encouraging words. Yet, at the back of her mind, there was still a nagging doubt.

Soon after, there was another transatlantic call, this one from Dr. James A. Lehman, who was such a good friend of the family and who had performed the surgery. He, too, tried to assure her that her father was doing well. Yet, she also heard him say that she must forget about the family reunion planned for mid-June in Ireland, where a cousin was to be married. She had looked forward to the wedding, but most of all, to the joy of seeing her father again, and her mother, and the whole family. It seemed so long since they’d all been together. But, now, the doctor was telling her that her father would not be up to the trip; that it must be postponed indefinitely. Was he telling her everything?

And it was, then, that she knew she had to see her father. Her husband agreed; she should fly at once. But the decision was so sudden, that there was no time for Rainier to arrange matters of state and go with her. He would have to stay home and so would the children, Caroline and little Albert. Two capable nannies would look after them well.

It would only be for a few days, but she and her husband had never been apart for more than a few days since their marriage. And now, though it was his birthday, he insisted that she go to her father’s side. There would be a lifetime of birthdays for them to share.

Not fast enough

In the hospital corridor, a red light blinked on and off over a doorway; a patient signaling for a nurse. But, as she sat waiting to be admitted to her father’s room, the blinking signals seemed like the lights that had flashed on and off at the wing-tips of the plane carrying her to him. She had stared, unseeingly, out the window at those lights. The stewardess had told them, when they took off, of the jet’s incredible speed. Yet, how slow they seemed to be going, how very long the trip seemed. It was the fastest way, and yet it wasn’t fast enough.

When they had to make an unscheduled refuelling stop at Rykjavik, Iceland, she had remained in her seat, twisting her hands in impatience. Finally, they landed at ldlewild, and she gratefully let herself be whisked through customs and immigration, then into a waiting limousine by helpful New York City police. Then she was speeding in a car on her way to Philadelphia. At last she would see for herself, how her father really was.

But, now, after all that hurrying, she sat waiting with a door closed between them. She shivered, a little, at the persistent cling, cling of the bells ringing out their code call for doctors who were needed on the floor. It was an urgent sound; it meant that behind one of those closed doors, someone was sick, perhaps dying, and needed help. Tired and tense with apprehension, she tried to shut the sound out. It would help if she could only turn her thoughts away from the frightening present and back to the years when she was “Big Jack” Kelly’s daughter and he had seemed so tall and strong—a solid rock of a man, a man it was impossible to ever imagine ill.

She had been third of his four children, but she was the only one who was “different”—quiet and dreamy and lost to the world half the time. Peg and John Jr. and Lizanne were so much like Dad that it was hard not to get a left-out feeling sometimes. Yet, she couldn’t keep up with their games and sports. She wanted to be with them and to feel sure everybody loved her, but she was always coming down with another sinus attack . . . And she wasn’t very good at games, anyway.

She was the shy and tremulous child who hung back on the family outings, holding her mother’s hand while the adventurers ran ahead with father—exploring, shouting out discoveries, noisy and happy. In her own secret way she was happy too, but so sensitive that at the sign of a rebuff she felt she could curl up and die! Because of this, she was more dependent on her parents’ love, she needed it more than the others. But how can a painfully uncertain child be sure that she deserves that love? That father can be as proud and fond, in his own gruff way, of the “quiet” one as of the others.

Suddenly, she heard a soft rumbling and she saw that the stretcher—no longer empty—was being rolled past her again on its way to the elevator. The figure on it was so blanket-wrapped that only the face showed—a man with eyes closed, mercifully asleep.

She, too, closed her eyes. There was so much to remember. There were the old family stories the Kellys loved to tell and retell. The one about the day of her own birth that she’d heard until she sometimes felt she could actually remember it happening.

The message

It was in 1929, a year that, to many, was the beginning of the end—the Big Crash. But to Jack Kelly, life was good—or maybe it was because he’d worked so hard for it, being a man nothing or nobody could stop. He’d started out pushing a wheelbarrow and he’d gone all the way up in business, in sports, and in politics. He was a civic leader who had come very close to being elected mayor of Philadelphia. Out of “Kelly brick” he had built a large, gracious home for his family:

To such a man, the Depression was nothing you allowed to mar the big day your third child is born. Nothing would do but to drink a toast in champagne to the new baby. She could imagine how he’d looked that day, tall and proud with his laugh booming out. And then, when the bottle was empty, he had put a note into it. Nobody saw what he had written, and nobody was to take it out and look. It was for Grace’s eyes, but not until the day she turned twenty-one.

When the time came, she took out the note and read a message that was short and simple—hardly more than a few words: “I hope you grow up to be as nice a girl as your mother.”

The father who had written that bit of sentiment and keep it a secret for twenty-one years—how was he today? She looked toward his door again, as if willing the nurse to come out and end this suspense.

But the waiting went on. . . . There had been another message from him—Seventeen years ago her father had written it in freshly-laid cement in the driveway at home. She knew the words by heart. “November 12, 1943.

Grace is fourteen today.” Long after he was gone, those words would endure. He—the builder—must have known that.

There was still another message that she would always remember, though it was only in the spoken words. It was when she knew for sure that she wanted an acting career—and wanted it on her own, not on the reputation and contact of her uncles. For she was the niece of George Kelly, who wrote such hit plays as “Craig’s Wife” and “The Show-Off.” And Walter Kelly, the famed “Virginia Judge” of vaudeville. But, above all, she was the daughter of Jack Kelly, who’d made it on his own, too.

She was about to enter the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York. Her father talked it over with her, asking her only to be sure. He told her what he knew from his two brothers, that show business is heartbreaking and demanding.

“You have to be good,” he said, “or we don’t want you to go.”

It was the crossroads for a girl who had everything. On the one hand a warm, welcoming home, family and friends, a privileged life of comfort. In the other direction hard, hard work. Had her father always known which she would choose? She chose the work, and turned out what he wanted her to be—good. She became a star, and Academy Award winner. She was noted for her beauty, talent, poise, bearing. She played a princess in “The Swan” and looked more regal than a real one.

A fairybook romance

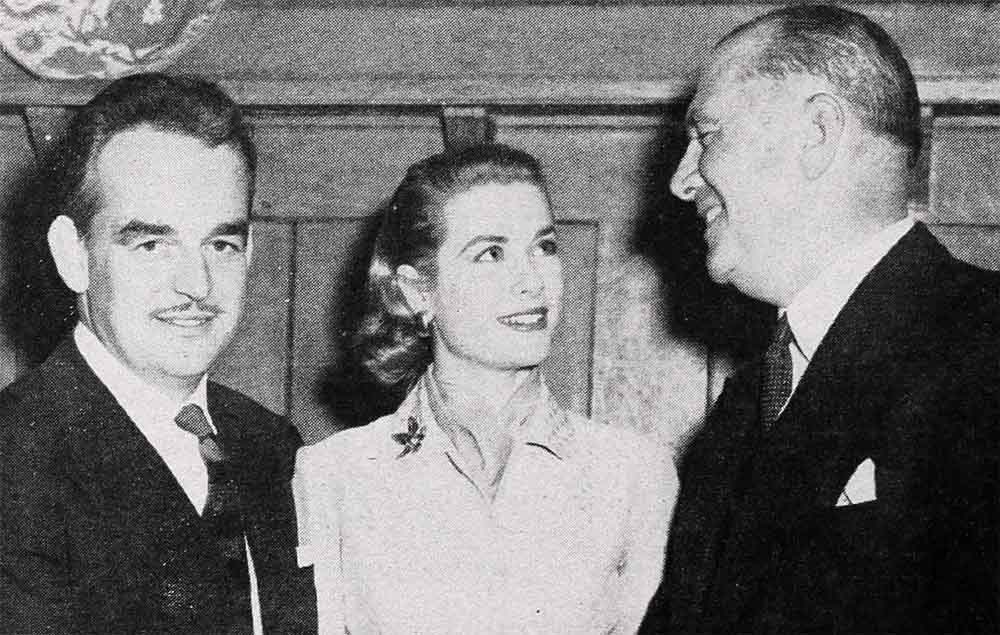

And, then, like a fairybook romance, a real prince did come. A young, handsome prince—but so shy, that his personal chaplain, Father Tucker, had to play Cupid and do the talking for him to Grace’s father. Even then, with a prince asking for his daughter’s hand in marriage, Jack Kelly was so much the protective father, and so thoroughly an American, that he didn’t leap at the chance to make a princess of his daughter.

He said to the chaplain, “Father, all we know about this boy is your word that he will be a good husband.” And he said, “Father, let’s get this straight, we’re not running after royalty.”

Now Grace remembered Father Tucker’s answers to her own father during the conversation that shaped such a happy, love-filled life for her and Rainier. Father Tucker had said, “John, I wouldn’t recommend any boy to any girl if I didn’t know him inside out. . . . he is a fine boy. And you’re not running after royalty, royalty’s running after you.

The running after—those were only words, figures of speech. Her father knew that what mattered was two young people falling in love with each other. So the announcements went out. “Mr. and Mrs. John B. Kelly Sr. announce the engagement of their daughter Grace to His Serene Highness, Prince Rainier III of Monaco. . . .”

And she remembered how, in the unbelievable stress and strain of an international wedding, her father had stood by her to hold off the curious ones and the pushers.

Yes, he had given her his protection, his strength, and a great deal of love. Jack Kelly, wrapped up in business, sports and politics, may not have been one to talk about his feelings for the shy, quietly intense one of his children—but he was there when she needed him. Always. With such a father, the question was inevitable: What would I do without him?

She looked up and saw the nurse coming out of his room, toward her. She stood up at once.

He wouldn’t see her cry

“You may come in now.”

Now she would see her father. What the doctor had to tell her, he would tell later, and then she could release the tears, whether they were of relief or despair. But now, while she was in this room, her father would not see her cry. Because he was so sick—and she loved him so dearly.

She walked swiftly along the corridor. Only for one moment, at the very door, she stopped. She turned away, alone within herself. The nurse didn’t see her face, with its look of fear, or her hands pressed tightly together and against her body for control. She said a silent little prayer, took a deep breath, and when she turned back, again, she was ready. The look of anxiety was gone, her face wore a serenity that was lovely to see. A smile of greeting was ready on her lips.

Two weeks later she was on her way home to Monaco—knowing what she knew. That for her father it was what she had dreaded all along. Cancer.

He was out of the hospital now; the doctors had let him go home to be surrounded by his family again, in the reassuring comfort of his own house. Because for Big Jack Kelly, that man made of iron and steel and brick, now it was only a matter of time. Yet, at home, he attended shows and made jokes about having been hospitalized.

Grace flew home to the family whom she had left for a few days that lengthened into two weeks. She went knowing that this visit with her father had been something very precious. She would always be grateful for it, always have it to remember along with everything else dear and good that she remembered about him and herself. All her life she would remember the birthday note in the champagne bottle, and the birthday card in the cement, and all the other unspoken ways he had shown his love. And for comfort she would have, too, the memory of these two weeks they had been blessed with. Two weeks of close, warm companionship—before it was too late. Two weeks in which she could talk to him, and do small services for him, and keep up the brave smile. Because if John Kelly knew the final bitter verdict, he had too much courage to admit it. And how better could she have honored his brave, proud heart than by never showing grief in his presence?

But she went home with the burden of her knowledge heavy on her own heart.

And a week later she was winging back to him. This time with Rainier by her side. For death had come abruptly, sooner than she anticipated.

Now Grace Kelly could weep. Her father could not see her cry.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1960

AUDIO BOOK