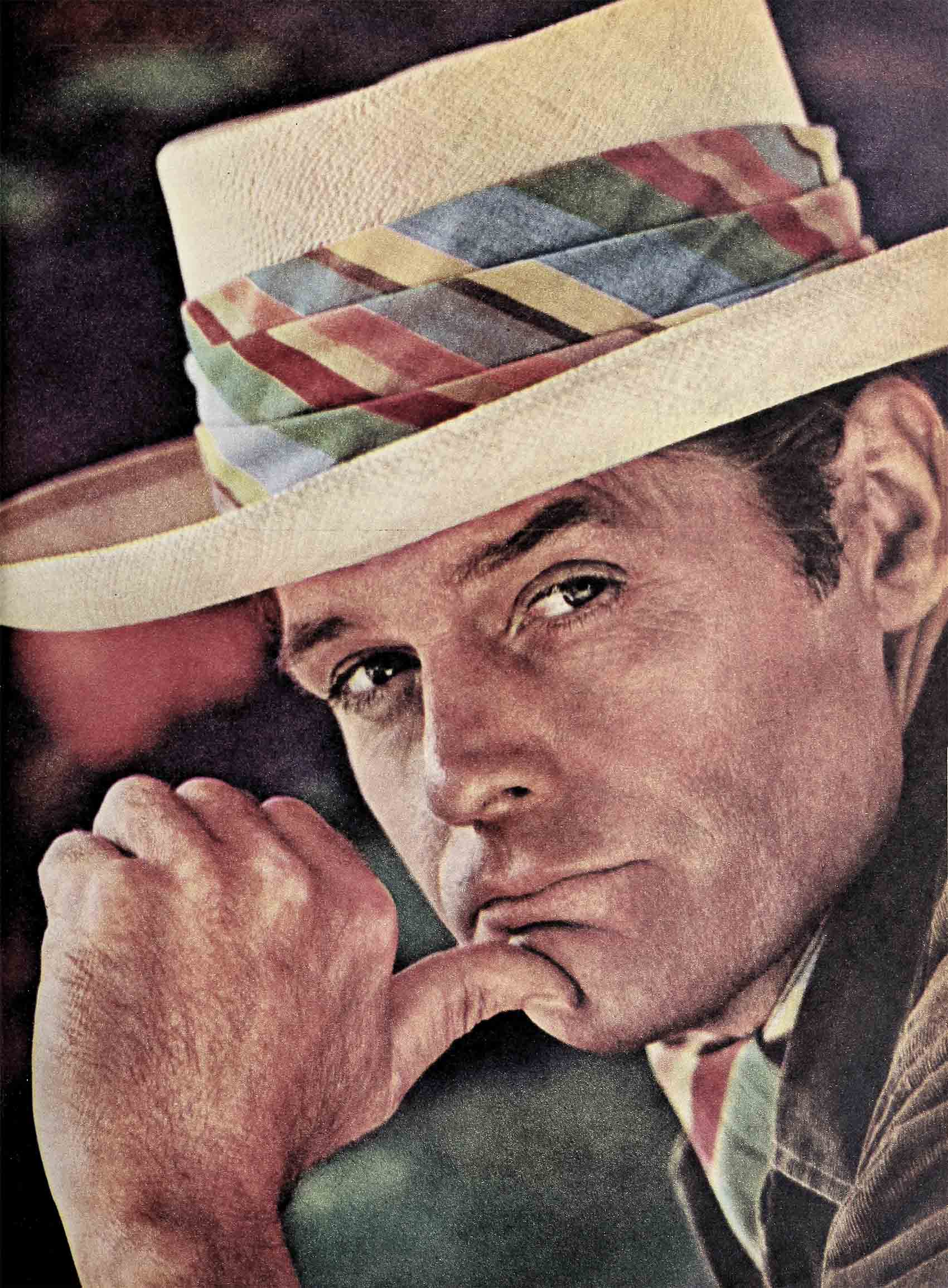

Jack Lord: “I’d Be A Bum Without Her!”

My wife is one of this world’s great people, a tiny French woman with a nineteen-inch waist—and strength like a rock! In a very subtle, very feminine way, she has opened doors in my life that had always been slammed in anger. In a marvelous way she has steadfastly refused to see the flaws in me. Before I knew what was happening, I found myself trying to live up to her ideals of me. For the ten long wonderful years of our marriage, I’ve been trying to be the kind of a person that she thought I always was. You know those lines of Kipling’s: “She showed me the way to promotion and pay. And I learned about women from her.”

“I also learned a few things about myself—a guy who’d gone through life settling everything with my two fists—a guy who’d slugged his way through a hundred brawls and somehow had always gotten by . . . who shipped to sea (at fourteen the first time) came up the rough way, through the hawse pipe, learned to hold his own in a scrap and never did learn to curb his temper.”

Jack Lord—TV’s own Stoney Burke—leans back in his chair, stretches out his long legs and his sailor blue eyes dream back to the sea, which was one of the great influences on his life. Something in his blood, actually—his dad was the executive of a steamship company, and in Jack’s boyhood was running five ships in the China Sea. He told fabulous tales of the sea to which Jack and his brother listened rapt. And he had a fantastic library which they read.

“My mother was a real Irish matriarch,” Jack said. “In most marriages, you find one strong and one weak. Not in this marriage. They each had their own function, their own strength to add to the tandem. Maybe that’s where I got my ideas of what a marriage should be. And they had no objections about my going to sea.”

The sea came first

To sea, at fourteen, in school vacation . . . and at fifteen . . . and after high school he went to Fort Trumbull Academy at New London, Connecticut, and earned a third mate’s ticket in the Merchant Marine. Sure he was going to college—but first the sea!

“On ship there are men who are saintly and men who are bastardly.” Jack says. “There’s always some bully who wants to push you around and always a guy who’ll defend you if you need it. I spent five years at sea, free, reckless, ready for anything. Hundreds of ports of call and every one of them a new world.”

He was on a ship that broke down in Cape Town, South Africa, and rather than ship back, he hired on as a steelworker in Persia, ten bridges between Khorramsher and Tehran.

He was an able-bodied seaman on one of the first ships that went through the Mediterranean when it was reopened after World War II. This ship was the Kelly Hall, a Liberty ship, ten thousand tons, passing down through the Suez and headed for the east coast of Africa. In the tropical heat, the refrigeration system broke down and all the meat on board spoiled overnight. Then all the dry stuff was invaded by weevils, so that the ship was really crawling. The only edible food was canned and they didn’t have too much of that. The crew got together and appealed to the captain to put into port and get some decent food supplies. Captain Kidd—a good loyal company man.

“I’m eating this food,” he said, “and if it’s good enough for me, it’s good enough for you.” They were en route to Durban, passed Mozambique, there were plenty of ports available, but the captain refused to stop. So the night before they landed at Durban, to make sure they got fresh supplies, the men broke into the storeroom and threw everything overboard—the rotten, fetid meat, the weevil-infested flour and cereals, everything. Captain Kidd promptly charged them with mutiny—he wired ahead to the American consulate and arranged for every man jack of them to be thrown in jail upon landing.

Very few of the crew were actually sentenced to jail, and Jack, a member of the Seaman’s United Protective Union, went off scot free to new adventures.

Once he missed a ship and was courtmartialed. Luckily, he had won $2,400 the week before in a crap game in Bahai, Brazil—there’d been a Navy gun crew aboard and he’d cleaned them out. Then he’d loaned the guys back their money so they could go ashore. At the court-martial, an ensign appeared and vouched for the fact that Jack couldn’t have deliberately missed the ship, it was an accident. He could prove it. He owed Jack $600, others owed him as well, and he’d certainly not give up that kind of money!

“A two-fisted sailor man”

There were plenty of fights. As Jack says, “The men who follow the sea never really come to terms with the world, for the most part they’re guys running away from themselves, the lost people. It was great when I was a kid, but you have to grow up. And when you do, looking back, you feel a great compassion for these men, they have no direction and no future, just freedom.”

But when he first came off the sea, he kept right on with the two-fisted part of the sailor life. It wasn’t a matter of booze—this man doesn’t drink. It was always a flash of temper. Self will. He’d gotten himself a job in the swank Cadillac agency on West 52nd Street, a good secure job at a good secure salary with pension plans, the opportunity of learning about financing and the opportunity to deal with people of great means—a job for life. He was top salesman on the floor when one day he threw a potential customer out of the showroom. Bodily. Not only a potential customer, a duke. This arrogant gentleman had strutted about the showroom and at one point, as he was examining the cars, said haughtily to Jack, “Hold my cane!”

“ You hold your cane,” said Jack evenly. “I’m not a cane holder.”

The duke waxed obnoxious. Jack heaved him ho.

It caused quite a flutter in the staid Cadillac emporium. The General Motors executive in charge summoned Jack up-stairs.

“Just exactly what did you do?” asked the boss.

“I threw that guy out.”

“And what right have you to throw out a customer?”

“None. He was obnoxious and nasty, I thought he needed to be thrown out.”

And expected to be thrown out himself. But the old man paced the floor muttering, “Dammit, what am I going to do with you?” And nothing happened. The boss had grown up in a rough area of New York City, as Jack had. He understood.

“I’ve been blessed with people,” Jack says. “You know, they say that angels watch over sailors, drunks and fools. I was a sailor, and I guess my guardian angel was on hand. Not too long after that, I found another guardian angel—Marie.

“My last fight was shortly after she and I were married. I was still working at Cadillac, was driving in Manhattan at high noon one day and this taxi driver bumped me. Now this is the kind of a guy I teas. I stopped, got out, advanced on that cabbie with blood in my eye. He must have sensed my antagonism, he reached through the window and threw this punch at me. A big, tough, 240-pounder. I pulled him out of that cab and there in the middle of Broadway and 42nd Street at high noon, worked him over. When I finished he was a wreck. I know. I paid his doctor bills.

“It was nothing new to me—just one more scrap—only this time I had to tell Marie. It was very difficult telling her. I’ve never been in another fight since.”

As a matter of fact, Jack’s life was changing at this point. He was moving into quite another sphere and channeling his energy into a fight—but not with his fists—for his life. Not the life of the sea which he’d had; not the life of the Cadillac agency, he’d had that too; but a secret life he’d kept locked up in him since childhood, when his dad had taken them to see every show on Broadway.

Ten blocks away from the Cadillac agency was his dream—the theater. But how to get there? One day, the manager called Jack onto the floor to meet a tall, painfully shy man who was looking at a 75 limousine. Gary Cooper. Jack was shaking like a bird dog and his easy flow of conversation was suddenly paralyzed. The two of them walked around the show room. Coop said nothing. Jack said nothing. After a while it occurred to Jack that this guy was, like himself, a car spook. He started talking about cars, about an old Cadillac 12 he’d taken apart and put together, about a Pierce he’d once had, and a Duesenberg. “Duesenberg” proved the magic word that unlocked things.

Fellow Duesenbergers

Coop lighted up, his blue eyes sparkled, “I just came back from Plattsburg,” he said. “Went up to see a Duesenberg I once owned.”

The movie star had traveled five hundred miles to see an old car!

From that minute on, the two men became friends, it was a friendship that was going to last until Gary Cooper’s death, That first day Jack asked him what he’d never dared ask anybody. “How did you really get started in show business?”

“Well, you have to have a galvanized gut,” Coop said. “You can’t take no for an answer.” He’d gotten his start by scraping together enough money to have a test made, on a horse. He hired the cameraman, bought the film and sent the test around.

Jack made his own start. He went to Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse and said “I want to be an actor. I think I should learn how to act.” Meisner wanted to know why . . . where he wanted to go and why . . . and after a four-hour interview Jack was admitted to the evening class. A couple of months later he quit his job at Cadillac. December, 1952. It was a major decision and Marie very definitely helped him make it.

“We hadn’t been married very long and it was asking a lot, for me to go to her and say I’d like to drop an $18,000-a-year job for nothing, a venture into the strictly unknown, and against such odds. There are very few women who will sacrifice security—it’s a necessary thing for most women—for all women. They should have it. But I had a dream and I was afraid of being trapped by my comfortable job, my comfortable hours, my comfortable income. So I told Marie and she said fine, she was all for it. I told you she was tough. She is. And she believed in me. kept believing, even though it took me a year and a half to get my teeth into anything substantial.”

Jack’s first real job was with Ralph Bellamy on “Man Against Crime” which he did for peanuts. His break in the theater with Kim Stanley in “The Traveling Lady” on Broadway paid $500 a week, but it wasn’t the money that mattered, it was the open door. In nothing flat he was in Hollywood to make “The Courtmartial of Billy Mitchell”—with Gary Cooper.

“Well.” Coop said when they met on the set, “the guy who likes Duesenbergs!”

Marie and Jack make their home now in Hollywood in a two thousand-square-foot apartment which is their ivory tower. “It’s furnished with things we love, our books, my photographs, our art collection. We have no children, no relatives, we are everything in the world to each other.

“I talk everything over with my wife. I don’t go around the corner without her and I don’t do anything without her. She’s a true friend. This great relationship, this marriage, is the most important thing I ever did in my life. What I was looking for, all those years in every port. Everyone’s looking, I think, consciously or subconsciously. You’re always hopeful you’re going to open that door and she’ll be there.” And Jack was a charmer, never at a loss for romance—that’s probably why he missed that ship and was court-martialed. But once he found what he was looking for, he didn’t hesitate. This chic girl with her dark eyes and hair, her flair for costume design, became Mrs. Lord as quickly as he could manage it. From that moment he was on his way to his life: work uniquely his and a mate uniquely his.

“I was thinking the other night,” he says, “there are times in this business when no one believes in you except yourself—and there are times when you even lose faith in yourself. Any actor worth his salt has these moments of doubt, and anyone who says he doesn’t is a liar. This is a business in which you’re knocked down so often and so hard, you’ve got to be able to get up on the nine count. It’s what Coop called the ‘galvanized gut.’ I’ve got it and scars to prove it.”

His wife “gentled” him

But he’s also developed a gentleness and calm which, he says, he owes to Marie. “You can’t imagine how my wife worked on that gentleness.”

And there were the three men he admired—all dead now—who were the combination of toughness and gentleness which, before Marie, he would never believe existed. They were Coop, and actor Walter Hampden and lawyer Joseph Welch.

With Coop it was a “basic, genuine humility, an inside goodness—like the pure in heart shall see God. There wasn’t a mean or vain or petty bone in the man’s body. In a business where personalities clash and conflict, he was always above it—perfectly capable of fighting, but not, needing to. He was never down on the level where the carnal minds seem to operate. And knowing him was a reassurance that nobility and honesty do pay off. Marie adored Coop, as I did. Marie was a starry-eyed little girl around him.”

Walter Hampden was seventy-four when Jack made a picture with him and found him “stimulated and stimulating—and gentle.” Then he met Joe Welch, who had just put Senator McCarthy down at his hearings and come off the conquering hero. Now he was to make his first appearance as an “entertainer” in a three-part “Omnibus” series. Jack played John Marshall and Joe Welch did the narration. He and Jack had an immediate rapport and treasured their friendship to the day of Welch’s death in 1960.

“Now that I think of it,” says Jack, “the men I’ve admired most were gentle guys who were really rocks. And I thought you had to take people apart!” Now he knew what Marie was talking about.

Jack Lord is a lucky man. He found himself a girl who believed in him and made him believe in himself. A talented designer, she was perfectly willing to give up her business as soon as he was earning a living in show business. Now she works much harder than she ever did for herself. While he’s working she is up every morning at 3:30 to bake bread and muffins for his “longshoreman’s breakfast,” his big meal of the day. He rises at 4 and by 4:30 is devouring eggs, sausages, potatoes and hot muffins.

“She’s a homemaker as my mother was,” says Jack. “She has created, decorated and maintains our home, orders the food, cooks for me, does many many other things—selects my wardrobe, goes with me to the tailor for fittings, coordinates the colors, answers most of my personal correspondence, works a good deal harder than I do. She rarely comes on the set. But always the last day we have lunch—it’s sort of a ritual,”

Jack is ready for the big screen again. He turned down a major part on Broadway to make his next move—either the lead in “Gold Finger.” another James Bond story, or “Watch Over Your Land.” C.O. Bolton’s novel to which Jack bought the film rights. He and his Marie are just back from a trip to Europe where they discussed co-production with Dino De Laurentiis in Italy and Tony Richardson in England.

What an itinerary for their first trip to Europe together! The Cannes Festival, a month in Rome, then Paris and Madrid; a drive up through the Loir Valley and welcome guests at a chateau in which their friend Terrence Young owns a twentieth interest, and where Alexis Lichine, top wine authority and the greatest chef in Europe, holds sway.

Success, of course, has changed their lives, “but only in superficial ways,” Jack says. “The basics don’t change. We can have a lovely home, Marie can have help, she can get her clothes at Valentina and Balenciaga and Dior instead of designing her own, and having them made up. But in their clothes or her own designs, this is the most chic woman I’ve ever seen in my life. You should see her walking down 57th Street in New York. A dozen people will turn to look at her. She wears hats well, has a great figure, she’s very small, five foot two inches, tiny-waisted, but what the French call false maigre—meaning it’ll fool you, that little figure.”

Yes, Jack’s quite aware that there are actors who fall in love with every leading lady; he feels that they’ve never known happiness, they’ve never built a solid structure, there’s always been a Haw, that’s why their marriages crumble. But not for him. There are standards he’s set for himself, standards she’s helped him set; this marriage is the rock on which he’s built a life and a career.

“She is the one with faith and I never discount it. I kid her about it, but I want it to be true. She’s got great spirit, this girl, and I want more than anything to become totally the man she thought I was from the first. I had no stability, no goals, no direction. She’s my stability, my goals, she’s everything.

“You know the truth? Without her, I’d have been a bum.”

THE END

—BY JANE ARDMORE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1963

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023Really wonderful info can be found on web blog.