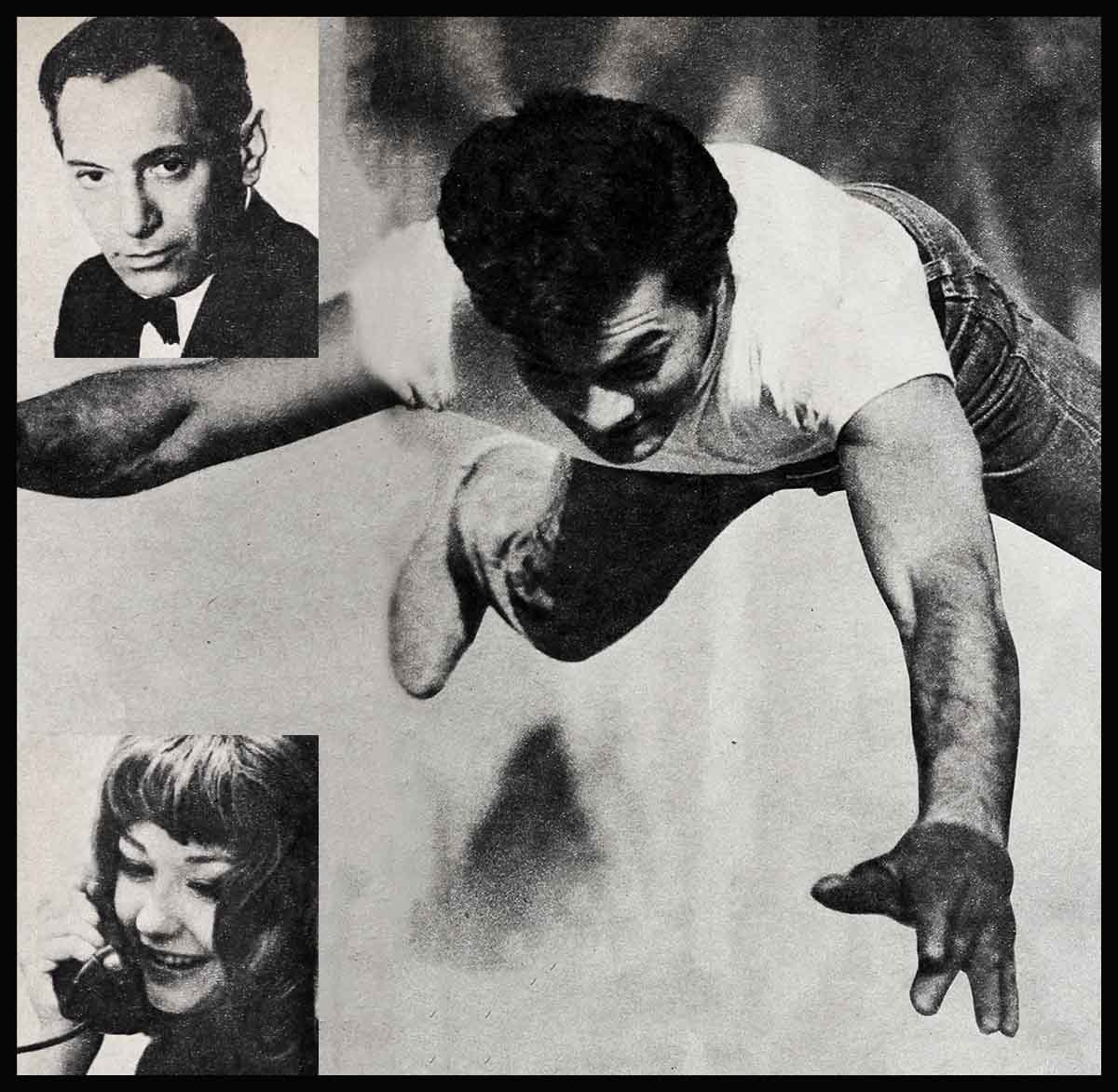

How This Man Enabled Tony Curtis To Fly To This Girl

“It happened on location,” Tony Curtis said. “We were up at Tahoe shooting ‘40 Pounds of Trouble.’ A gorgeous Saturday . . . Danny Kaye and I were lounging around Harrah’s Lodge. Danny was appearing there but he didn’t go on until midnight and I had the afternoon off. Danny, who can never sit still, suddenly jumped to his feet and said, ‘Okay, let’s go. We’ll fly around, catch a glimpse of Virginia City . . . zip down to San Francisco . . .’ I said, ‘Who, me? Are you kidding?’ I thought everybody knew I didn’t fly. Not for ten years. Not for any cause whatsoever, not even if it means a slow boat to Brazil, France or Norway. But it was Danny who thought I was kidding. He takes planes like a New Yorker takes taxis. Flies his own silver Beechcraft all over the country. To him it’s part of a modern vocabulary, today’s living. Pretending planes don’t exist—it’s like pretending cars don’t exist, he said, and why don’t I ride a horse to the studio? Then, when he realized I was really scared, he started talking like a Dutch uncle. Had I ever tried to do anything to get rid of the fear? Well, of course I had. Psychiatry. Plenty of it. Danny kept walking back and forth and then he snapped his fingers as if he had found the answer and said he knew just the thing. Hypnosis. Had I ever bumped into Arthur Ellen? No? Well, Ellen was only the greatest, a night club sensation who’d hypnotized all kinds of people. He was the one who’d saved Jackie Jensen’s career with the Boston Red Sox when Jackie’d quit the team because he was terrified of flying and couldn’t keep up with their schedule by train. Last year Arthur Ellen hypnotized Jackie, and after that he flew from Boston to L.A. for the game with the Angels. He’d get Harrah to get in touch with Arthur Ellen, Danny said, if I was willing to give it a try.” That evening, a dark-eyed man wearing a natty fedora of sheared beaver rapped on the door of Tony’s suite. Harrah had located him at his home in Northridge (just outside of Los Angeles), and Ellen’d flown right up.

“Hey, dig that crazy hat,” Tony said.

The two men shook hands. They’re the same height, about the same build, Ellen has a few silver streaks at the temple, they have something in common—a warm, genial ease of manner, a quick communication. The living room of the suite was buzzing with people. They walked into the next room and closed the door. Soft-spoken Arthur Ellen told how he’d met Tony Martin in Las Vegas three years ago. Tony was to open that night, he’d lost his voice with laryngitis, the club hadn’t found anyone to replace him. Pandemonium! They’d met in a store where Martin was using sign language to buy a few shirts. Ellen had taken him into the stock room, sat him on a stack of boxes and hypnotized him. That night Tony sang—and well.

“Laryngitis is often a manifestation of anxiety,” Arthur explained to Tony. “Even a great pro can be unconsciously nervous when playing Vegas where a great deal of money’s involved, where he wants to do his best and outdraw the competition. Under the relaxation of hypnosis I’m usually able to demonstrate to a subject that he’s able to do the very thing he hasn’t the conscious confidence to do—whether it be to sing or to stop smoking. “In Pittsburgh I ran into a young girl who’d survived a malignant brain tumor operation at seven. At seventeen she was still in a wheel chair, atrophied, unable to walk. Doctors could find no reason why. Her mother and father came to the Monte Carlo Club where I was playing and asked me to come to the house. Under hypnosis, I took her back to the moment when, just before anesthesia, she heard two nurses discussing how sad it was she’d never walk again. Within minutes, Tony, I had her on her feet—walking. Of course the subject is the one who determines the success or failure of the venture. It depends on your own sincere wish.”

On wings of love

Tony had two very urgent reasons for wishing—sincerely—that he could be cured of his aversion to flying.

One is Christine Kaufmann, the seven- teen-year-old German actress with whom Tony is in love. Christine of the sexy face and figure was then in Berlin making “Tunnel 28”—only a handful of hours from Tony in Hollywood if he’d fly to her on wings of love (and a jet). But by train to New York and then boat to Europe, Christine was but a distant dream. Who can afford time for that kind of leisurely courting—especially now that Tony is no longer just an actor.

Which brings us to Tony’s second reason for giving ear to Arthur Ellen: Tony’s burgeoning career as producer. I’ve known him since he first came to Hollywood and I’ve never known anyone more bent on learning, enlarging his horizons, growing into the man he wants to be, than Tony Curtis. He learned to fight as a little street tough—with fists and feet and anything else that was handy. When Ire determined to learn how to act, he fought hard to learn. He longed for security, he fought toward it. When he found that swallowing twenty years of education and social know-how in two was a little confusing, that the complexities of his and Janet’s lives were pressure-producing, he wasn’t afraid to ask for help and to learn from that help. He regarded analysis as his college education.

But evidently even psychiatry didn’t dispel his fear of flying. And successful as Tony is, the one thing hampering his career has been this inability to fly, with its resultant lack of flexibility. Ordinarily he is a man who makes every minute count, but on this one score he wastes actual months of time traveling by train and boat. This bottleneck must be as frustrating to him as it must be to his production people.

“Okay,” he told Arthur Ellen now, “I’m afraid and I’d like not to be. It has nothing to do with what people think of me, it’s for my own sake. I’d like to be free.” “Look at me,” Ellen said—the same words he’s used on more than 40,000 subjects in the last twenty years. “Now relax loosely . . . sleep deeply.”

As simply as that. Tony was asleep. Some people fight hypnosis. He did not.

“Now talk to me, Tony,” the hypnotist said. “Let’s go back and find where the fear started. . . .”

Tony went back . . . all the way to his h first trip to Hollywood. Bob Goldstein, then Eastern talent scout for U-I, had seen him in “Golden Boy” with the Cherry Lane Players in Greenwich Village. He had called Tony in for an interview. Three days later, aboard a luxury airliner for the first time, he was en route to Hollywood and scared to death. Suppose he never got there? Suppose something happened? He sat tense as a robot from La Guardia to L.A. He vowed that if he ever got there and if he ever got a toehold in the business, he’d take care of himself, he wouldn’t take chances, he’d never jeopardize all that Bernie Schwartz had dreamed of.

Now Arthur Ellen led Tony back one step further. Now he was Bernie Schwartz, signalman aboard the submarine USS Dragonette . . . he was helping load torpedoes in Guam . . . a winch chain snapped, struck him, he lay with both legs paralyzed for four weeks. That was when the boy who was to become Tony Curtis really had time to think for the first time. To know that if he ever could walk again, acting was for him. He’d had a taste of it before the service but now nothing would deter him. If he could only walk again. . . .

Well, he walked. And he got that contract at U-I. And his star began to rise. And he married his dream girl Janet. They flew all over America making public appearances. They flew to England for a benefit. Then they did shows for the Air Force camps in Germany.

Tony’s fear showed

“We spent most of our time in the air, in Army planes that carried on dauntlessly in all kinds of weather,” Tony recalled. “They were dauntless, I wasn’t. I never did like flying and I didn’t want Janet to know I was scared. But of course she knew. I took sedatives to calm me down. Then one night we hit a fog so thick, we couldn’t see the window sills—until a motor caught fire and lit things up for us. I wasn’t just scared, I was in a state of shock. Somehow we managed to land and fire engines, ambulances were waiting—the whole bit. When we got to our hotel I walked in and collapsed.”

Tony never really expected to fly again after that. But he and Janet were in Europe, they spent that first Christmas in Paris, knowing no one except themselves. They found a scraggly little tree and a few berries and tinsel to trim it, they called up home and talked to Tony’s parents and to Janet’s. They walked the streets, looking in windows. When, at last, they were free to go home, they flew.

On the last leg we flew into a headwind that even turned the crew green,” Tony said. “I’ve never been through anything like it. When we finally landed (years later) at the Los Angeles airport, I made a vow: ‘No more. That’s it.’ And it has been.”

The hypnotist rationalized. Of course Tony’d been over-protective in his desire not to let anything hurt his career, a kid from a basement in Hell’s Kitchen with the chance of a lifetime! That was where the fear stemmed from. Certainly he’d had experiences in the air—but just because of an impulsive vow, why make oneself suffer for the rest of one’s life? “As soon as you realize that it’s infantile to have to cling to this all your life. . . .”

“But there are an awful lot of crashes,” said the peacefully sleeping Tony, his brow slightly furrowed.

“And car crack-ups and train wrecks and people falling in their own bathtubs and breaking their necks,” Ellen listed. “We live in an era of speed. Why make your own life difficult? Isn’t everyone better off getting places quickly, transacting business quickly, seeing the people that matter quickly?”

Tony listened. He said no more. The hypnotist waited a moment. Then, softly: “Your sleep is coming to an end. You are waking.”

Tony opened his eyes. He shook his head, grinned and said, “When do we go up?”

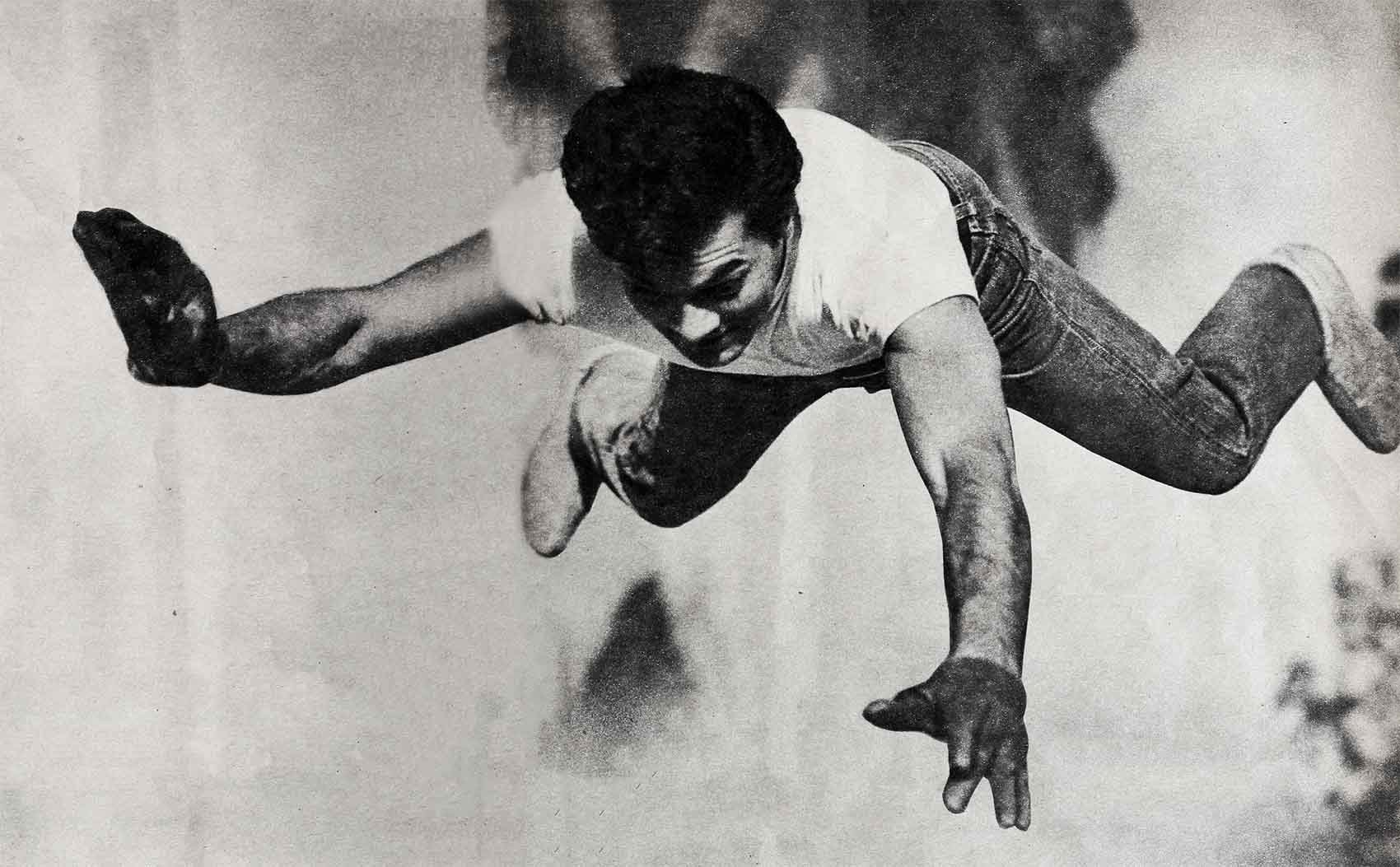

The next morning he got Harrah’s pilot, Bob Woods, and Harrah’s plane and up they went—Bob, Tony and Arthur Ellen.

“I had to go, I didn’t dare stay behind,” laughs Ellen, recalling the hectic day.

The U-I people were screaming protests, you’d have thought Tony was taking off in a balloon. Their concern was the picture. The picture was only half through, suppose something happened? They were still arguing as the plane took off and left them behind.

“I can only tell you it was the most wonderful experience I’ve ever had,” Tony says now, looking back to that day of liberation. “I felt like a kid. free, absolutely free, not a trace of the jitters. We went straight up like some great gull, circled around. Bob Woods let me take over the controls. Do you know what that feels like? You feel as though you are able to do anything. I want a plane of my own, I want to learn to fly. It’s like being the captain of the ship, only greater. Such wonder and delight! I’ll swing that route!” Now he was an enthusiast!

Short hop—a starter

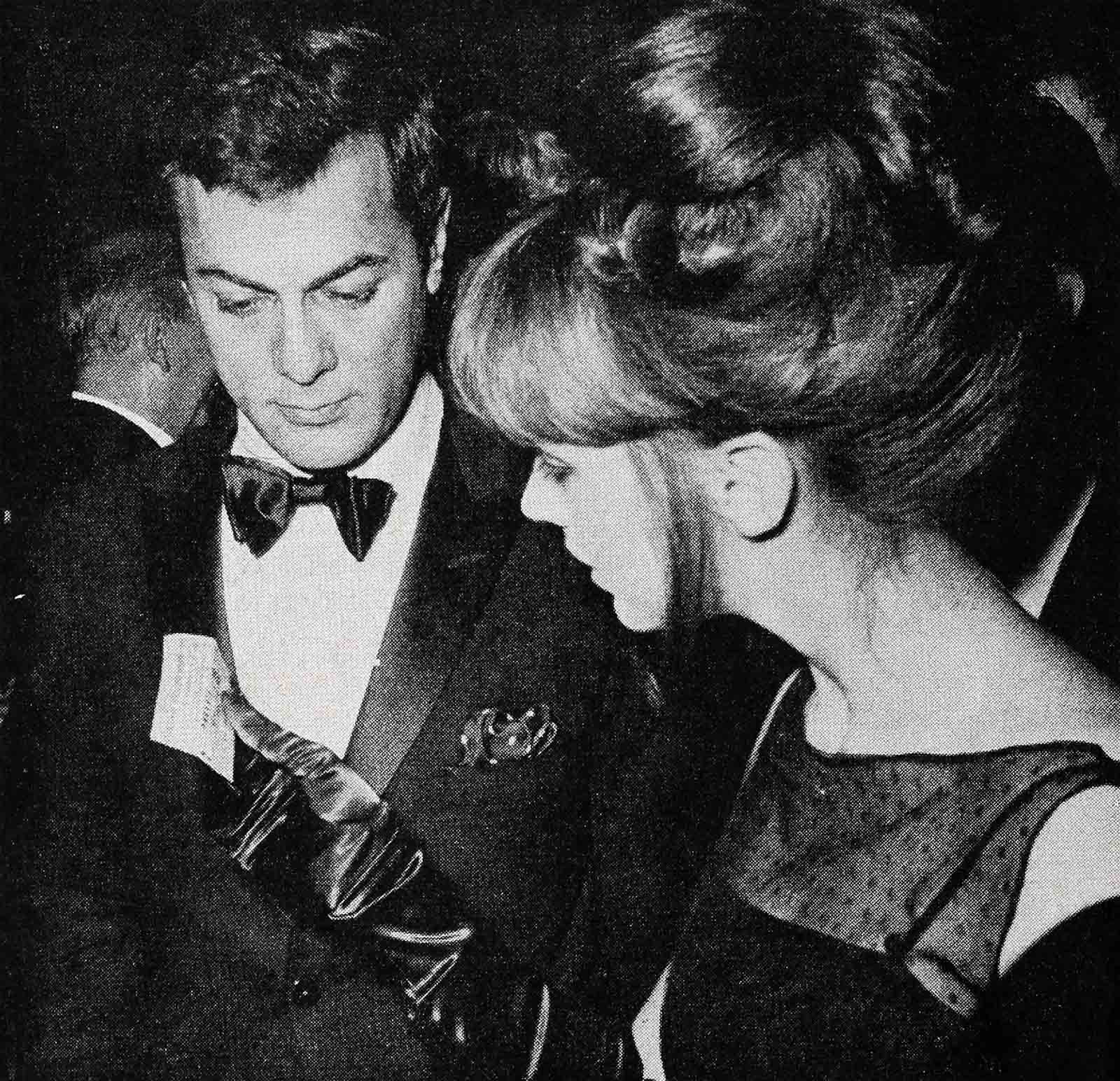

Three days later, Tony flew home to Los Angeles on a commercial plane, playing cards in the lounge with Phil Silvers, Hi Goldberg and Sheldon Bronson. And on his head, Arthur Ellen’s smart sheared beaver hat. Before he left Tahoe, they’d become close friends. Tony wanted to know all about hypnosis and Arthur told him—how when he’d begun, there was no place to even learn about hypnosis, no place to study, you didn’t dare discuss it. Now there are courses at the New School for Social Research, part of the study of treating neuroses and psychoses, the American Medical Association has recognized hypnosis. Ellen himself has conducted courses for physicians at universities throughout the country.

He told Tony how he’d worked with Jerry Colonna and Johnny Mathis (just before Johnny started his career, when he was so tense, so terrified, that his voice was constricted); with Buddy Hackett, Dennis Day and Vic Damone; with George Gobel’s bursitis and Liberace’s block against a specific Paderewski passage.

Tony wanted to know if the effect always lasted. Ellen explained that under certain circumstances the effect is permanent, but sometimes it’s only temporary. A lot depends on the honesty of desire—sometimes a person volunteers to give up smoking, but only out of mere curiosity, daring the hypnotist to rout their negative thoughts.

When Tony’s imagination is captured, there’s no one like him, and Tony’s imagination was captured. “How’d you like to be in pictures,” he kept asking Ellen. “One of these days I’m gonna make a part for you in a picture.” One night they wandered over to a night club where Kay Starr and Frank Gorshin were billed. They sat at the back, no one knew they were there. When Frank came on and got his first big round of applause for singing, he made a little speech.

“I have to tell you a story,” he said. “I’m probably here under false pretenses. Twelve years ago, I took my wife to a night club in Pittsburgh and volunteered to be hypnotized by the fellow who was putting on the show. He told me I looked a little like Tony Bennett and he thought I could probaby sing like Tony Bennett and that ten minutes after I came out of hypnosis, I’d sing for the audience. I did. I sang ‘Because of You.’ My wife almost fainted, because I’d never sung in my life, not even in the bathtub. I was a bank teller. But I’ve been a singer ever since that night.

“Now the funny thing—this same hypnotist, Ellen, is due to open right next door at Harrah’s and I’m dying to catch his act. But I’m afraid to. I’m afraid he might snap his fingers and I’d be a bank teller again!”

How Tony laughed! He’s told that story to everyone on the U-I lot. He’s had Arthur Ellen come visit on the set, and he tells some of the hypnotist’s wonderful cures.

There’s no doubt that he did good for Tony. Right after “40 Pounds of Trouble” wound up production, Tony flewto Europe. The week that he saved gave him time to tour five cities, plugging “Taras Bulba,” to carry out some public relations jobs for the State Department and to visit his late father’s birthplace in Hungary. And to be with Christine before the start of “Monsieur Cognac.”

Admitting that aviation is here to stay, Tony says, “Hypnotism has changed my life.” He’s an imaginative man, an intelligent and honest one, and he knows there’s nothing left to fear except fear itself. He’s come a long way and he’s planning to go a lot further—and faster. But above all, the new Tony can now fly to the arms of the girl he loves—Christine—no matter I where she is.

—JANE ARDMORE

Tony and Christine are in UA’s “Taras Bulba.” His next film is “40 Pounds of Trouble,” U-I. Hers is UA’s “Tunnel 28.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

No Comments