Brooklyn Eagle

People hoped that Marjorie and Jeff Chandler would settle the differences that parted them. This was no lip-service hope, but the McCoy. In self-protection, studios generally view the emotional upsets of their stars with objectivity. The Chandler case proved an exception. Out at Universal gloom greeted the news. As one girl wailed: “Sure, I’d feel worse if it happened to me, but not much. You can’t even take sides, they’re both so swell.”

A year ago, the Chandlers would have been left in peace to work out their problems. Now, with Jeff emerging as a top screen personality and an Oscar Award nominee, everyone wants to get into the act. It’s the same old price you pay for prominence, and it can’t be helped.

Jeff said of his break-up with Marjorie, “It had nothing to do with Hollywood. I get tired of hearing Hollywood made the goat. It had nothing to do with my being an actor, except in so far as actors are strange people. To want to be one, you’ve got to have a neurosis, so maybe actors are more susceptible to the things that cause break-ups. Maybe. I’m not sure. Who doesn’t have a neurosis? My father was a silk salesman, married to a Russian girl. Their marriage broke up. My wife’s parents were a Midwestern girl and a newspaper man. Their marriage broke up. None of the four was remotely related to greasepaint.”

Chandler’s a friendly person, direct, easy to talk to. neither spilling over at the edges, nor playing hide-and-seek behind his face. As he talked he seemed to have been addressing his hands, folded quietly on the table. Now he looked up.

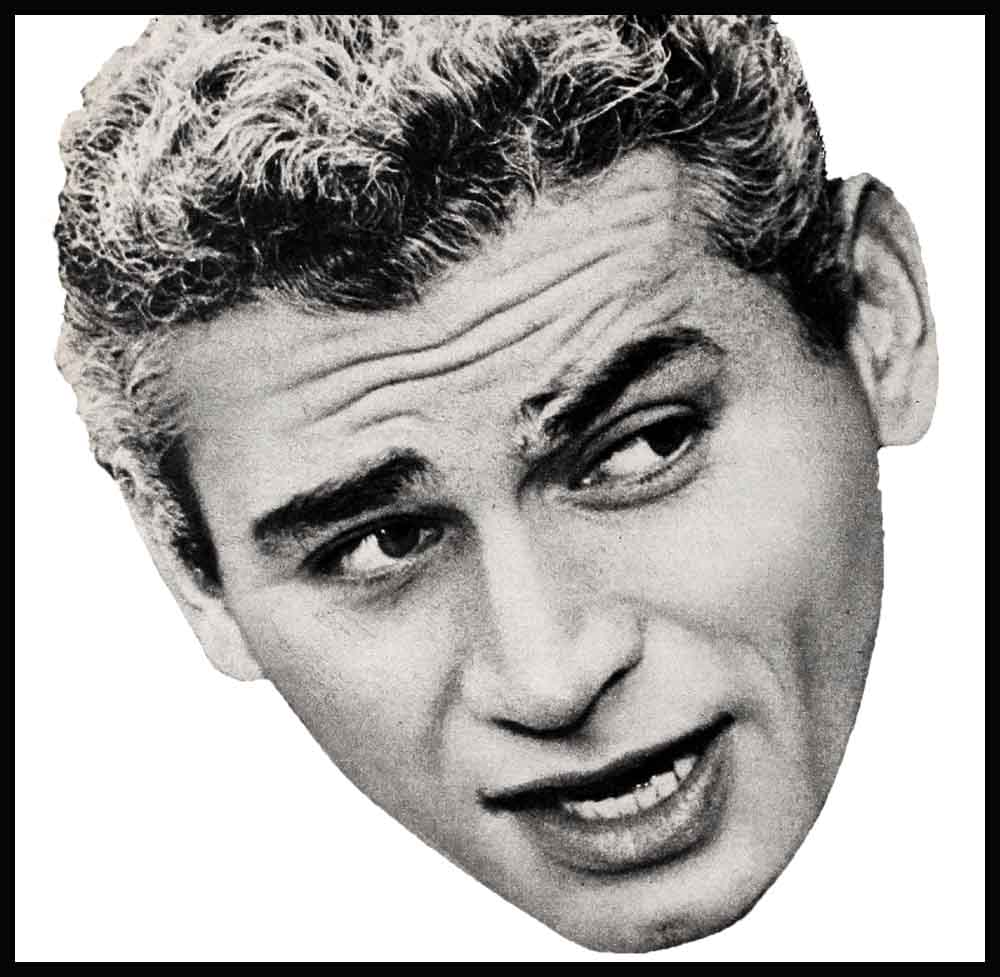

Actually, Jeff’s highly articulate. Humor glints in his eye and laces his speech. His prematurely graying hair makes him seem older than his thirty-two years, and he gives you the same feeling of inward strength that marked him as Kurta in “Sword in the Desert,” as Cochise in “Broken Arrow.” So completely did he make these parts his own, that it’s hard to separate them from the man. Which hands him a laugh now. For years they told him he was the mug type. They said, “if Mazurki doesn’t want the job, we’ll call you.”

Then an agent named Meyer Mishkin came into his life, Mishkin studied the deep-set eyes with their trace of melancholy, the expressive mouth, the lean, six-foot-four frame carried with ease and authority. “You know something?” he said mildly. “You’re a leading man.”

Jeff maintained his composure at the time. “But my ego wanted to jump up and kiss the guy,” he says.

According to Chandler, earlier screen tests had been met with cries of pain. Allowing for hyperbole, it’s clear that he’d made no dent on movie minds. In 1949, U-I called him to test for a minor part in “Sword in the Desert.” What magic Mishkin used to get the brass to consider him for one of the leads instead is his own trade secret. Unwittingly, the technical adviser did his bit. “That part was written for a man of fifty. None of our group leaders was older than thirty-two.”

Which clinched it. Mishkin called his client. “You’re not playing the part you tested for. You’re playing the fourth lead.”

Chandler dropped dead.

Before the picture was half finished, U-I had his name on a contract. After it was finished, Jeff, watching it unfold, slumped low in his seat, longing only to get out of there. “I don’t like my face,” he explains. “Especially enlarged. This didn’t, however, prevent me from getting Meyer on a hot telephone when I learned that Twentieth Century-Fox had ‘Broken Arrow.’ ”

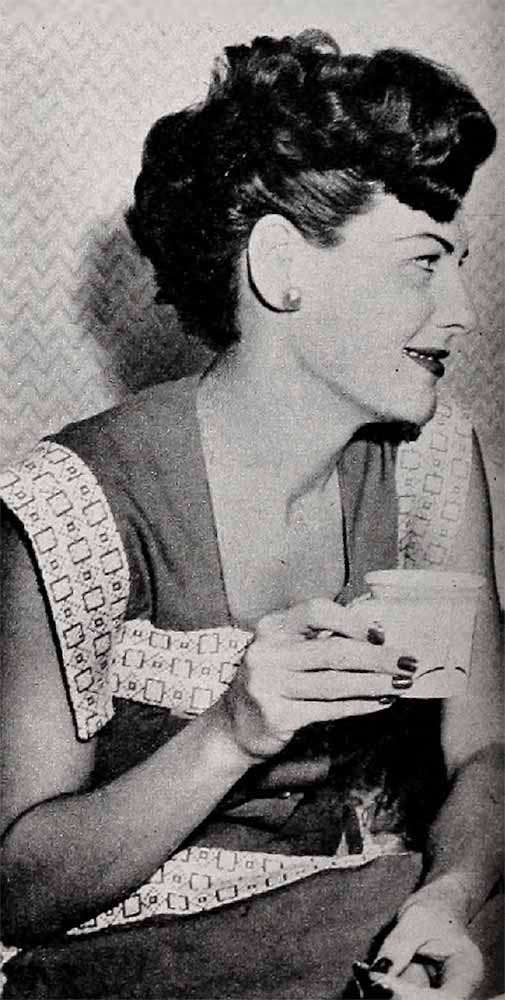

“Marge had a fair career of her own but she quit the whole thing for the kids”

He’d heard about “Broken Arrow” two years earlier from his radio agent, Don Sharpe. “Joel McCrea may buy it. And there’s an Indian in it you should play.” McCrea didn’t buy it. But Jeff read the book, and Cochise was in his blood.

Over at Fox, they wouldn’t listen to Mishkin at first. A persistent man, he bypassed the casting office and snagged himself a session with Delmer Daves. “I’ve never asked any favors. All I ask now is that you put Chandler’s name on the list of possibilities.”

His earnestness must have carried persuasion. They sent for Chandler and decided on a test. As a rule, such tests are rough around the edges. There was nothing rough about this one. Daves directed it, Jimmy Stewart played opposite Chandler, it was fully edited before being shown to Zanuck. And it turned out to be the only test made for Cochise.

On tenterhooks and on the home lot, Jeff was working in “Abandoned Woman” when Bob Palmer, casting director, hove into view, shaking his head, sighing, “Too bad, too bad.” Jeff’s hopes hit the familiar toboggan trail. Palmer eyed him sadly. “It’s a rotten shame, Jeff, you’ll have to shave your chest.”

“Broken Arrow” was shot almost wholly on location, so they didn’t see much of Chandler around Fox. But the minute his stills went up, the doves started cooing (studio parlance for a murmur and flutter among the secretaries) which is considered a fine omen by the front office. Out of a wallful of photos, visitors would invariably pick his. “Who’s that? Such a quiet face, yet so alive—” After the preview, a rival producer clapped a Fox executive on the shoulder. “Great performance. Sorry you’ve only got the guy on loanout.”

“Don’t cry,” said the Fox man, “we tied him up for six pictures.”

So they were pleased, but hardly astonished, when he was tapped for Academy honors. “Simple justice,” they said.

Chandler took it less calmly. People had been offering him bets that he’d be nominated—a steak dinner here, an ice cream soda there, a quarter with Sid Skolsky. He took them all on, naturally expecting to lose. This time he was working in “Iron Man.” As they broke for dinner, the unit manager came over, faking a busy hunt through his pockets. “I’ve got a piece of information for you here.”

“Don’t show me. tell me. I’ll believe you.”

“Believe what? It’s nothing. Some idiot item in some idiot paper . . .”

The item was finally produced. You can still see the hole in the ceiling where Jeff’s head hit it.

He was born Ira Grossel in Brooklyn, and Van Johnson’s partly responsible for his movie name. Having worn his own for almost thirty years, nothing else sounded right. Helpful friends made suggestions. He’d give them a brief whirl, then wriggle out from under. The subject began to weary his pals. One day he saw a picture called “Easy to Wed,” in which Van Johnson played a newspaper man named Bill Chandler. It rang less strangely on Ira’s ears than most. That night he dined with friends. “I’ve got a name.” The chorus of groans rose and subsided. “This time it sticks. Chandler.”

“And the first name?”

“W-e-ll . . .”

“What about Jeff?”

“Jeff Chandler. Sounds like an English cowboy.” He struggled feebly, but the faces closed in on him. “Okay, okay.”

Their host vanished and reappeared with a Bible. “Put your hand on this.”

“What for?”

“Put your hand on it, brother, never mind the what-fors. Now repeat after me: ‘I solemnly swear that from here on in, my name’s Jeff Chandler and finished’.”

His wife and mother call him Ira. To Sheila MacRae, a friend of ten years, he’s Jeff in one sentence and Ira in the next. Gordon calls him Jeff-rey, starting as a baritone and ending in the bass. By now Jeff answers automatically to all three.

In revolt against an over sheltered childhood, he grew an overdeveloped sense of independence, and hates having anything done for him—whether it’s a necktie to be chosen or an illness to be nursed. One generally brackets over protection with wealth, which is a fallacy. Jeff was the sun round which his mother’s world turned. They lived with her parents after her marriage broke up, and she worked at what she could—now in a factory, now as a practical nurse. Money was scarce and earned in the sweat of one’s brow. Yet she saw to it that the boy went to nursery school and that his clothes were good. But fears for her ewe lamb stalked her imagination. Years ago her brother had broken his leg on roller skates. On three separate birthdays, hardier relatives gave Jeff roller skates. His mother found good reasons why it was better that Cousin Leonard should have them. Her attitude was understandable. So was Jeff’s reaction. Differently constituted, he might have been infected by her terrors. As it was, he began to feel fenced in.

Through grade school and freshman year at Erasmus, he was an honor student. Then the realities began to assert themselves. His grandfather died. With her small savings, his mother ventured into business—a candy store complete with soda fountain. Jeff, already responsible. arranged his class schedules so he was through at noon. Between them, they kept the place open from six a.m. till midnight. After two and a half years, the store failed anyway and the savings were lost. Meantime, school grew shadowy compared with the grinding present and impatience for the future. You could pass, Jeff discovered, without studying much. Without studying much, he graduated at sixteen.

Then his mother re-married. Healthily aware that this was a good thing for both, Jeff realized this marked the passing of a dream. His dream had been twofold—to be his own boss and to take care of his mother. For the latter, there was no longer any need. Concentrating on the former, he went to work as cashier in a restaurant run by his father, who’d reentered the scene some years earlier to make friends with his son.

At seventeen he met a girl older and wiser than himself, whom he remembers with affectionate gratitude. She recognized growing pains when she saw them and helped him through the confusions of adolescence. “Quit lazing around,” she told him. “Don’t wait for the world to knock at your silly door. It won’t. Make up your mind what you want to do and do it.”

He wanted to be an actor. That he’d known from the time of his first appearance in a school play. So he took a course in commercial art. By Jeff’s youthful logic, this was more reasonable than it sounds. His skill in drawing had won him prizes at high school. “You can study art or dramatics,” said his father. “I’ll pay.” He could get an art course for $200, dramatics cost $500. Early conditioning made favors stick in his throat, but if it had to be a favor, the smaller the better. “I figured, as soon as the art course was over, I’d go out and knock ’em dead, make half a million and be an actor in five minutes! What a schlemiehl!”

In an upper Manhattan room at $4.50 a week, and helped by uncanny timing on his mother’s part, he got by. “Call it intuition, call it accident, all I know is I’d be down to my last nickel, wondering where next week’s rent was coming from, and there’d be a ten-dollar money order from my mother in Jersey. In principle, I shouldn’t have used it. But I used it.”

His spirit, however, remained unquenchable. The art course completed, he got himself hired by Montgomery Ward at eighteen dollars per, and found that his assistant was making twice as much. Jeff demanded and was promised a raise. Next week, no raise. “How come?” he inquired.

“It’s got to go through channels,” said the boss. “They have to pass on it here, then in Chicago—”

“You mean my little measly raise?”

“That’s right. This is a big organization.”

“It’s too big for me. Good-bye.”

Lesson No. 1: you can’t knock ’em dead at eighteen dollars a week or even thirty-six dollars. The thing was to free lance. He free lanced. “It developed,” says Jeff, “into a tremendous nothing. I went back to art school as an instructor.”

One of the students was also studying dramatics at the Feagin School in Rockefeller Center. She invited half a dozen chums, including Jeff, to a school play. Sitting there in the darkness, the forces working within him fused to decision. As if a clock had chimed, he knew that this was the hour. No more fooling around, wasting good time, good youth. “Make up your mind what you want to do and do it.”

Next day a young man appeared at the Feagin School. “Hello. I want a scholarship—” Not quite so abruptly, but he doesn’t recall the preamble. Only his own sense of urgency. “I’ll do anything—paint scenery, sweep floors—”

He’d picked his hour better than he knew. Classes were overloaded with aspiring Juliets, and men were at a premium. They asked him to read and withdrew in a huddle, out of which one of them broke. “Well, young man, you won’t have to sweep floors. Mr. Rockefeller does that—”

It was a great year, both for the training he got and the friendships he made. Sheila Stephens was there, who later changed her name to MacRae. So was the guy you now know as Jack Carter. Jack used to bring two huge seeded rolls for lunch, filled with everything in the icebox. These he shared with Jeff, who held up his end by investing a dime in two candy bars. Art still came in handy. He drew at night to pay for his room and board.

When it came to leaving, however, he and the school held clashing views. Jeff was offered room, board and ten dollars a week at the Millpond Playhouse in Long Island. To him, this was heaven-sent opportunity. To the school, it was a run-out. “Either finish your work here now or don’t come back.” He chose to follow his star to Millpond.

There it shone for a while. Though he slept on an Army cot, which his visiting mother regarded with horror, he was happy. Though they didn’t always get the promised ten bucks, he and the others were having the time of their lives, developing into an all-year stock company. Food, shelter and the theater sufficed till the cold winter of 1940 set in, and they found themselves craving a certain degree of warmth. Each weekend the producer took off for his cozy hearthside, abandoning them to their heatless dorms. On one such occasion they raided the cellar. Led by Jeff as supervisor of the troupe, they gathered a bucketful of coal, piece by priceless piece, built a meager fire and tried to get the deep-freeze out of their bones. Monday restored the producer to their midst. He called them into conclave, and he wasn’t kidding.

“I understand you used some coal over the weekend. Are you responsible, Ira?”

“Used it?!” exploded Jeff. “We mine d it.”

“You had no business to. That coal was supposed to heat the theater for the first two performances.”

Allergic to being shoved around, Jeff blew his top. packed his bag and went to visit his mother. For six weeks he stayed put in New Jersey.

Big things, however, were brewing. At Millpond he’d met Bill Bryan, whom he still refers to smilingly as “my brother,” so close was their friendship. Bill’s folks were starting a summer stock company in Marengo. sixty miles from Chicago. ‘I’m directing,” said Bill. “You’re acting and designing. How can we miss?”

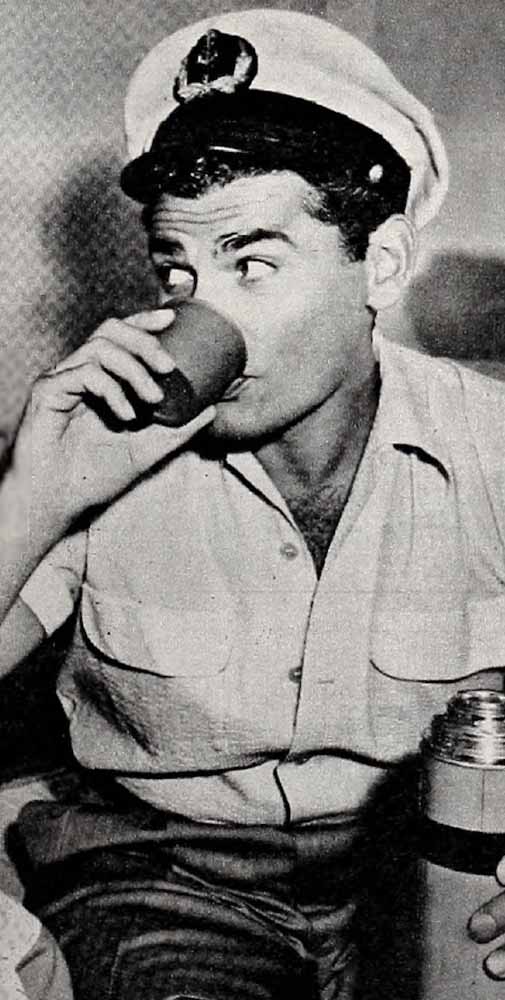

It was a gag, but it turned out to be fact. They wound up in the black, a rare State of affairs for summer stock in its first season. Life would have stretched rosily ahead, except that the fail of ’41 showed little rose-color. Both boys had been classified 1-A. They returned East, discussing the advantages of enlistment. Jeff plumped for the Air Force, but the Air Force was being choosy in those days. Candidate Grossel weighed in at ten pounds over the limit of 200. He was all set to apply to the Royal Canadians when Bill breezed in. “Hey, I’m in the cavalry—”

“You’re crazy—”

“Could be, but I’m still in the cavalry.” Bill was a skilled horseman. Jeff, a smart city cookie, knew one end of a horse from the other, and that’s all he knew. But a sudden sense of overwhelming loss engulfed him at the thought that his friend would no longer be with him. “Are there any more vacancies?” he asked.

“One.”

“Well, what are we waiting for? Let’s get it.”

Before the day ended, Jeff was a cavalryman. Toughest of all prospects lying ahead was that of breaking the news to his mother. In New Jersey he kept his bag hidden till half an hour before it was time to leave. Then he brought it out.

“What’s the bag for?”

“I’m going into the Army—”

She burst into tears. “Why didn’t you tell me sooner?”

“That’s why,” he explained, putting his arms around her. “To keep you from crying all night . . .”

. . . A year in the cavalry. Then O.C.S. and a lieutenancy in Army Aircraft. The Aleutians for two years, and back to Texas as a training officer Altogether four and a half years. From a boy of twenty-two to a man of twenty-seven. How does Jeff feel about those years? He shrugs. “They’re four and a half years that you put away, that you’ll somehow make up for and grateful for the chance, since you’re one of the lucky who came out alive and unhurt.”

In New York he met Marjorie Hoshelle again, whom he’d first met in Marengo. She was about to leave for Hollywood and picture work, Whether this had anything to do with Jeff’s decision to try Hollywood, you’ll have to dope out for yourselves. In any case, here came Jeff, primed with a wardrobe on which he’d spent one third of his savings of three thousand bucks, because for pictures you need clothes. Neither his clothes nor any other visible asset got him a look in.

As his bank account dwindled, he wrote letters to radio producers. Then he took further action. A hamburger joint needed a night counterman. “How about me?” asked Jeff.

The boss looked him over. “Sure. Starting tonight.”

It happens in stories, it happens in life. He got home to find a call for a radio show, and that was the beginning. If movies gave him the brush, with radio it was love at sight—or sound. Jobs snowballed. Before long he was hitting the majors with productions like Lux and Academy Award. A year later he had two shows of his own, and the following year became “Our Miss Brooks’s boy friend—a part he still plays for love as well as money, since in some ways he prefers radio to movies. “It’s not a mishmash with everybody’s finger in it. once you’re at the mike, you’re on your own, and you have to do it all with the voice.” Contrast the mild-mannered Boynton with Cochise, and you’ll see how a voice can distinguish character.

Back in ’48, prompted by Dick Powell, the movies took fleeting note of Mr. Chandler. At a radio rehearsal, Dick ambled over to him. “Ever think of working in films?”

Picking himself off the floor where the shock had bounced him, Jeff stifled a horselaugh “Yeah, I’ve thought about it.”

“Tell you what, come over to Columbia tomorrow. We’ll have a reading.”

Dick introduced him to the casting director. “This kid ought to be in pictures.”

The director’s eyes moved from Powell to Chandler to Powell. Jeff read and translated his thoughts. “All right, you so-and-so, if you want him in pictures, we’ll put him in yours.”

He appeared in “Johnny O’Clock.” If you remember him, you’re one of the few. Not till the advent of Mishkin, almost three years later, did he get a crack at performances you can’t forget.

Back in ’46 too, he and Marjorie Hoshelle were married at the home of friends. “Marge had a fair career of her own. She’s a good actress. But she quit the whole thing for the kids, and took a tremendous joy in my career. For a long time,” he says soberly, “it was pretty wonderful.” Then his face brightens. “And we have two wonderful children. They’re monsters, but they’re great—”

Four-year-old Jamie was named after a character played by Hepburn in “Without Love.” Jeff’s responsible.

“I always liked Hepburn, and I liked the flourish she gave to the part. It was fine with Marge. But when she picked Dana for the second, boy or girl, I got conscience-stricken. ‘Look, we’ve loused up one girl with a boy’s name, let’s not do it again.’ We settled for Deborah or Dana, depending on sex. Then in a softhearted or soft headed moment, I said, ‘Okay, Dana either way,’ thinking for sure it would be a boy. So Marge crossed me up and we had a girl. She’s Dana.”

So new is their rift that Jeff speaks of the past as if it were the present. “Wherever we go, we paint the walls dark green. It’s the only color that goes with the furniture. Maybe someday we’ll have the furniture re-covered . . .” At which point, he stops short.

You hope that someday they will have the furniture re-covered. Out at Universal, everyone’s rooting for Chandler and his wife to find happiness. As you leave him standing with the sunlight on his grizzled hair and his kindly eyes shadowed, you find yourself rooting too.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1951