Tracey Hillevi Davis—May Britt & Sammy Davis Jr.

The woman stared into the thin darkness of a false dawn and closed her teeth on a groan. A long moment, wrapped in pain, finally ended and ease returned to the woman. Clenched fists and feet relaxed, and the hard sinews in her neck softened into the flawless column of a white throat.

Her name was Maybritt Wilkens Davis (to moviegoers: May Britt), and her first child was supposed to be due in a month. It was a child unlike other children, for millions of people would be watching it from the day it entered the world.

Maybritt’s had been a difficult pregnancy, complicated by many factors. On her wedding day she had been ill with ptomaine poisoning, and she had conceived during the first week of her marriage.

She had tried to travel with her husband and to be his good companion during the early months of their marriage, knowing how desperately—far more than the average man—he needed her. Yet, when her weariness grew too great, she had been persuaded by her husband and her parents to return to Sweden for a visit. Those weeks in her native land had given her new strength.

Now she was back in California once more, living in the house she loved, the shelter she and her husband had planned as sanctuary for themselves and the children they hoped to have.

The pain returned, more terrible than before. She tied a knot in the corner of the sheet and bit the fabric so as not to disturb her sleeping husband.

The spasm passed and she dried her forehead with the back of her hand. The baby was not due for another month, so she must endure this false warning with the old, old fortitude of womankind since time began.

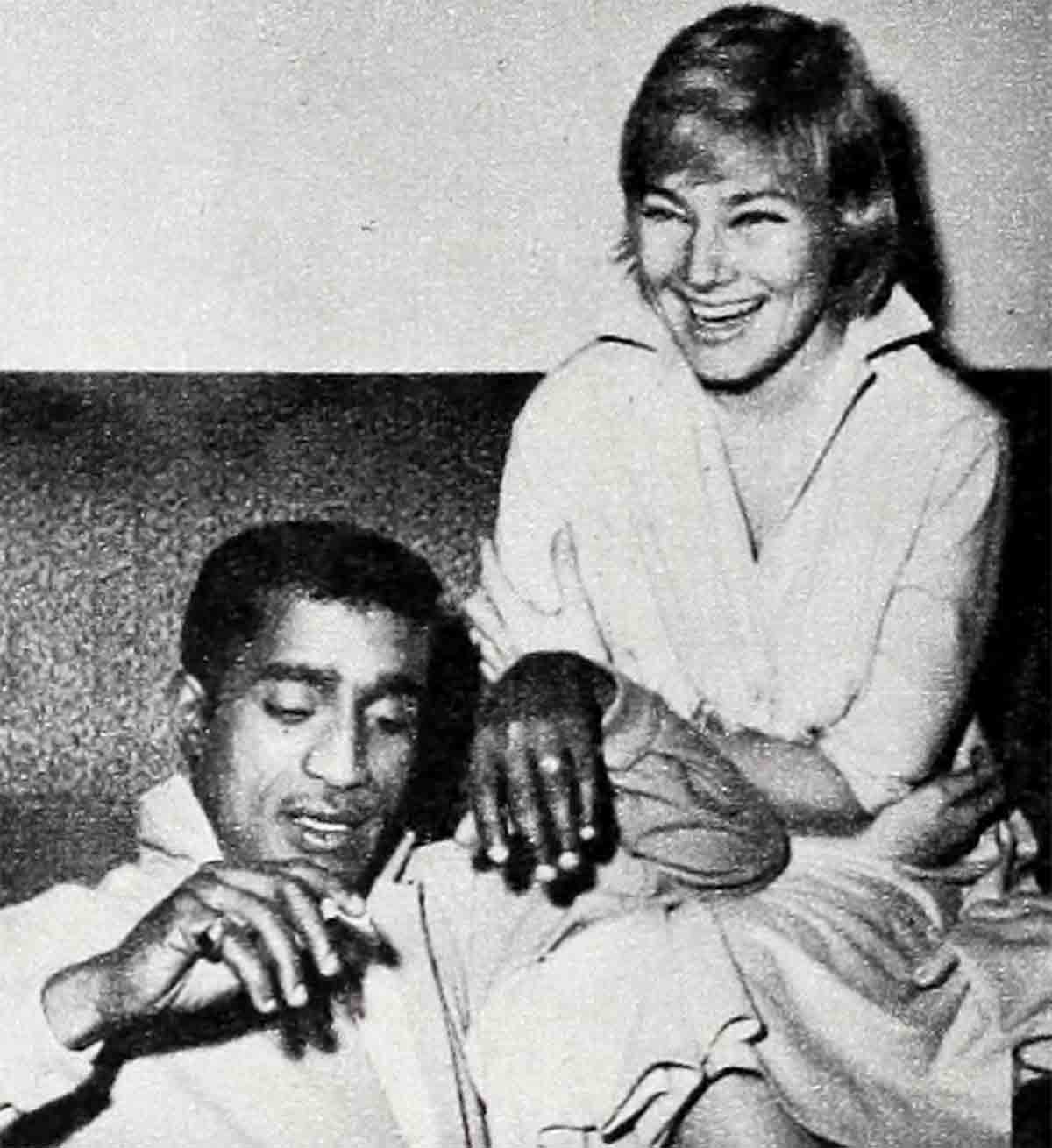

She turned her thoughts to happy times—to the night she had met her husband. At first she had refused to go to the party, as she had refused many other invitations. Hollywood parties depressed her. Conversation moved too fast, and often the quips were too slick for her unsteady grasp of English slang. Frequently, a tipsy guest would undertake persistent pursuit. Maybritt felt herself to be isolated, excluded, subtly different.

It was Barbara Luna, who had worked with Maybritt in “The Blue Angel,” who suggested to Sammy Davis Jr. that he telephone May personally if he wanted the Swedish actress to attend the party Sammy and his parents were hosting for Dinah Washington.

Maybritt had answered the invitation by saying, “No, thank you. I cannot be there. My mother is visiting me.”

“Bring your mother,” Sammy had suggested. “We’d love to have her.”

Instead, Maybritt brought a date to the party, a chap she had known for some time: a friend and nothing more. Almost immediately the friend went table-hopping, and Maybritt was alone.

But across the room she met the eyes of a man who was, without effort, a central figure at any party. In that swift glance, a spark of understanding and kinship leapt from one to the other. Casually, he moved toward her corner, bringing her into the vortex of a group. Through a trick of timing known only to a genius of show business, he slowed the tempo of the conversation without stalling it. The party still swung, but lento, not adagio. The easier pace picked up and carried with it the girl who had been excluded.

Sammy told Maybritt long afterward, “I go to lots of parties. I know what goes on in the minds of some people: Will I, as they say, keep my place? That’s the way it was that night. I was in the midst of the struggle again—trying to make them understand, without begging, that I was a human being . . . that although I knew they could tear my heart out if they chose, I trusted them . . . that I was not a freak, but a man with all the yearning for love and happiness they had. And right in the middle of all that, you walked in. I looked at you and you looked at me. Something happened inside and I cried out, in my mind, ‘Oh God! Don’t do this to me!’ But it happened. It clicked between us, and a door in my heart opened to a room I had never known before.”

An odd courtship

Theirs had been an odd courtship. They had moved in a group, in the midst of a perennial party. In Maybritt’s presence, Sammy once said to a member of his Singing & Marching Society, “Isn’t it wonderful to find a girl who’s lovely and intelligent and digs staying up until 6 A.M. watching movies?”

When Sammy went to London te fulfill a night club commitment, Maybritt made arrangements to meet her father, Hugo Brigg-Wilkens, in England, so he could meet Sammy.

Afterward, in describing those London days, May told a friend, “Sammy and I began by walking around the city in the wee hours of the morning . . . getting to the food depots already astir . . . watching men wash the streets, passing sleepy workers on their way to work, being stopped by beggars who, after a night in the park, are ready for the day’s ‘work.’

“Everything between us was natural and right. We could talk or not talk; we could look at a scene and know, without words, what we felt. We began feeling that we were quite happy together, that both of us were a complete unique thing, that we were no longer so lonely and sad. Contrary to what happens for most human beings, our love began at daybreak, with the first sunbeam.”

Sometimes Sammy talked at length about his boyhood in Harlem. Mainly the memories were a montage of stickball games on the street, forays in and out of gushing fire hydrants when the weather sizzled, nights spent backstage with his father and his uncle. He said, “My family was on relief, fighting to survive, for years. I was starving in vaudeville and burlesque from the time I was three years old. I never had a day of schooling in my life. I’ve never even been in a classroom. If I have kids, I want them to get as much education as possible. You know how some parents say, I didn’t have an education and I didn’t have a car, and I didn’t do this or that, so my children are going to make it up for me. I’m not for that, but I do want them to have an education. Only educated people are able to survive.”

And he said, “My father wanted me to become a big star. I watched acts and studied them from the time I was a little boy. I don’t know how to swim. I don’t know how to play baseball. I don’t know how to roller skate. I want my kids to do all those things—to have an ordinary childhood the way happy kids have it.”

In the midst of her thoughts another paroxysm caught and shook May. It was violent; it had meaning and purpose. It would achieve something magnificent.

But that other pain, the pain she had suffered when her friends warned her bluntly of the certain loss of her career and of other, more subtle, agonies should she marry Sammy Davis Jr.—did that pain have a meaning, a purpose?

She had been courteous to her critics; she had accepted their predictions with grace, saying, “It is possible we may happen to find hotels where we are not allowed to stay as husband and wife. There may be some states where we will not be received in the families. There may be public places where we will be obliged to part, owing to the different color of our skin. Well, let it be so. We will avoid frequenting these hotels, these places, these friends, and it will not be a great sacrifice for us.”

Sammy had said, “Actually, interracial marriages have a better chance for success than other marriages. I read about it in a survey by an English organization. The problems and pressures that surround a mixed marriage help bring a couple closer together. They have to stand together against criticism.”

And he answered the ultimate question with head-on resolve, “Of course we want children—about five hundred!”

The time is now

That had brought a thunderous denunciation from a Los Angeles social worker: “For the Davises to have a child is a plan of ultimate selfishness. Neither of them is considering the feelings of the child!”

A faint light gleamed against the draperies as Maybritt awakened her husband. This could not be false. The time must be now.

And, as uncountable millions of women have done since time began, and uncountable millions will do in days that are to be, she reassured a man who could scarcely shave himself, who was frantic because he couldn’t find his left shoe. “Don’t worry,” she said. “Everything will be all right.”

While he paced the floor, she sat before her dressing room mirror applying lipstick, eye-liner, eye shadow, eyebrow pencil, and combed her long blond hair with infinite care.

“Come on, Baby,” he said. “Are you okay? Let’s get going. The doctor said to like roll it.”

“I will not come out of that delivery room looking like an actress in white makeup, giving up the last breath,” she said, and she added another brush of mascara.

They drove through the mists of a California summer dawn. At the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, Maybritt was taken to her room in a wheelchair while her husband filled in the admittance forms.

The doctor told Sammy, “Better have some breakfast. This may be a false alarm, not at all unusual for a first baby. We may send your wife home in an hour or two.”

Sammy drank three cups of coffee in the hospital’s snack room. He is five feet six inches tall and has the complexion of freshly brewed java. He felt six feet seven inches high and as pale as Hamlet’s ghost.

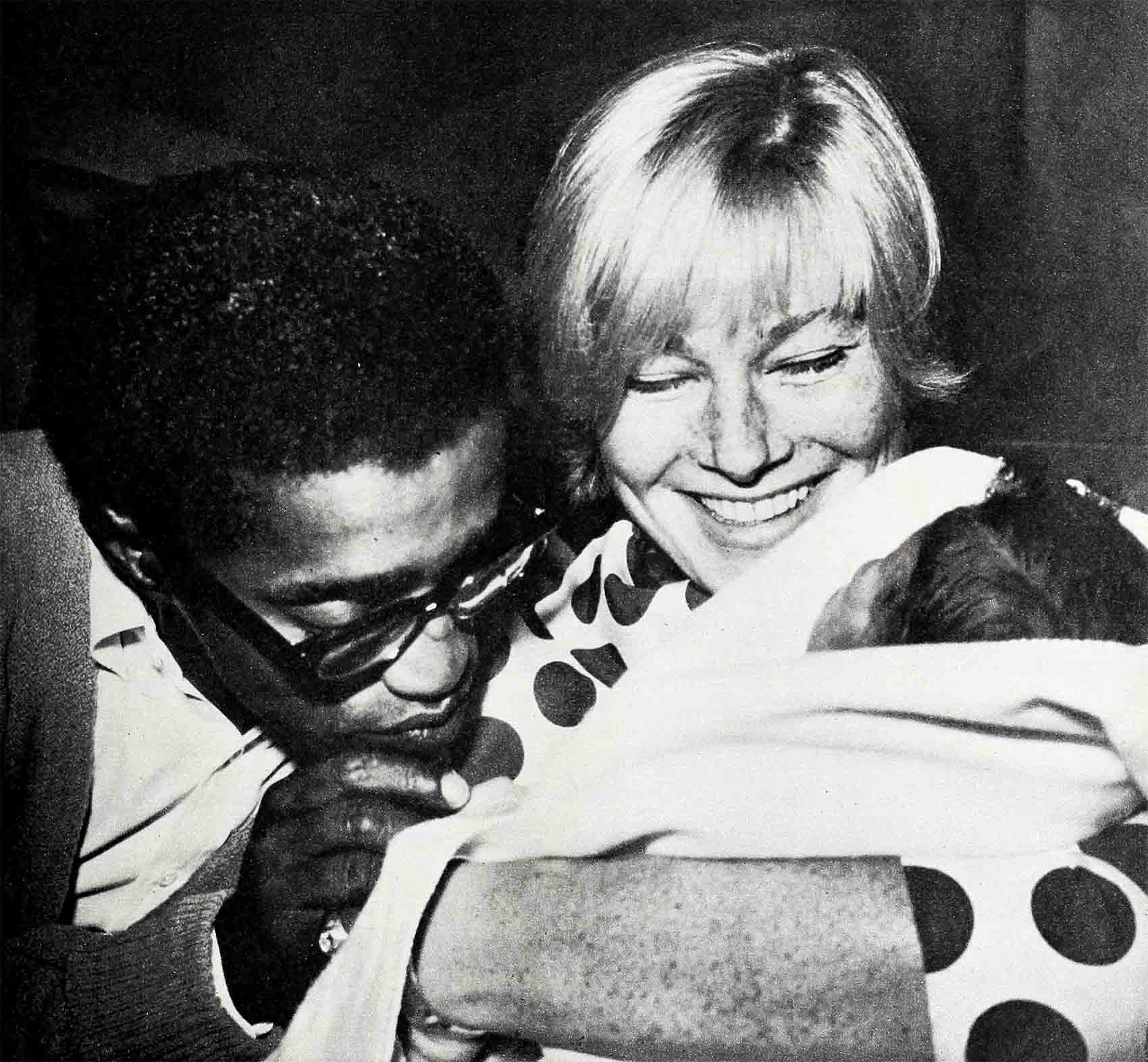

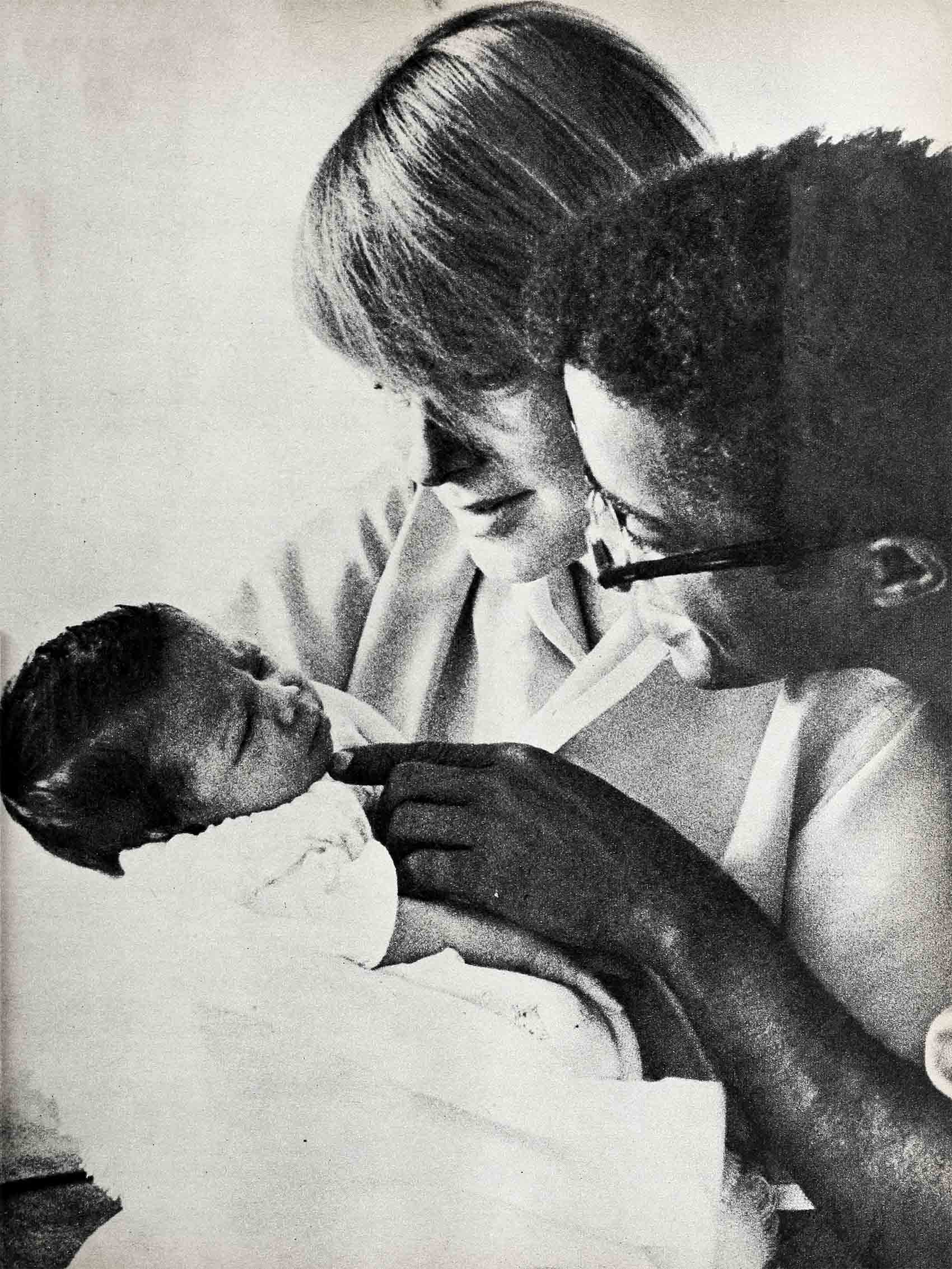

As things turned out, it was not a false alarm and Sammy was standing in the corridor as his wife was wheeled out of the delivery room. She said, “Hi!” and grinned. Her color was excellent: slightly suntanned with freckles showing through. Even her eyeshadow was unsmudged.

Sammy rushed to the nursery and stared at his daughter. The statistical card on her basket read, “Davis—11:55 A.M., 7/5/61—female. Wt.—7 lb. 7 oz. Ht.—19 inches.”

A nurse said, “If she’d gone full term, she would have been a Valkyrie—probably ten pounds and twenty-one inches.”

His eyes glued on the pink mite trying to gnaw her fist, Sammy asked the doctor, “Is she okay? I mean. . . .”

“All there,” said the doctor cheerfully. “I checked her over carefully. Right number of fingers, toes, ears . . . she’s perfect. A little beauty.”

If a beautiful child walks down a city street, every passing woman will notice the child, but not one man in fifty will pay the slightest attention. Yet, when a man looks upon his firstborn, he discovers in himself the very depths of awe, wonder and incredulity. Before him lies a miracle: love become tangible.

Sammy Davis Jr. kissed his daughter with his eyes, and closed his fists in a shiver of rapture. He had once told an interviewer, “There are only three ways a colored cat can make it: as a fighter, a ballplayer, or an entertainer. But he’s got to make it, see? I remember one time a guy asked me, ‘How far you going to make it, Sammy?’ And I said, ‘I’ve got an agent, some material and talent.’ So the guy says. ‘Yes, but you’re colored.’ And I said, ‘I can beat all this.’ ”

He had beat “all this,” and his success was to become his daughter’s heritage.

White, black or polka-dot

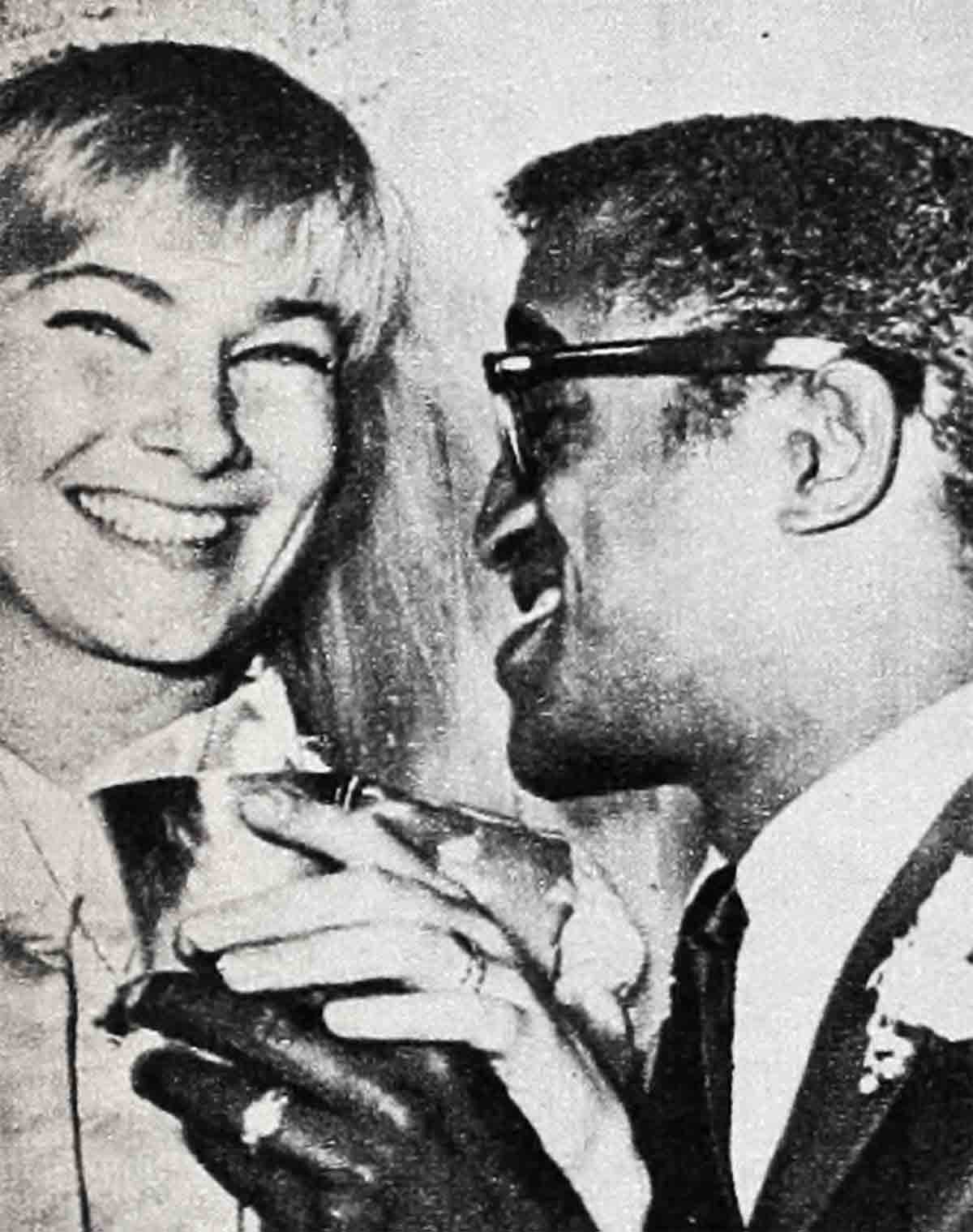

He telephoned the studio. announcing. “She’s a girl. This is the happiest day of my life.”

When he stormed onto the set, he was welcomed with elaborate nonchalance. Somebody said, “Only onebaby, Sammy? Coupla years ago in Canada—jackpot! Five kids at once.”

Peter Lawford said, “Big deal. I played tennis all day yesterday, and I feel fine even though my youngest is only three days old. Why you sweatin’?”

Dean Martin said, yawning slightly, “Amateurs. Now, take me—been through it nine times.”

When Sammy’s grin remained glued, and he couldn’t think of anything to say except—“It’s a definite gas!”—friends pummelled his shoulder and shook his hand. Soon there was no mouth on the set without its cigar.

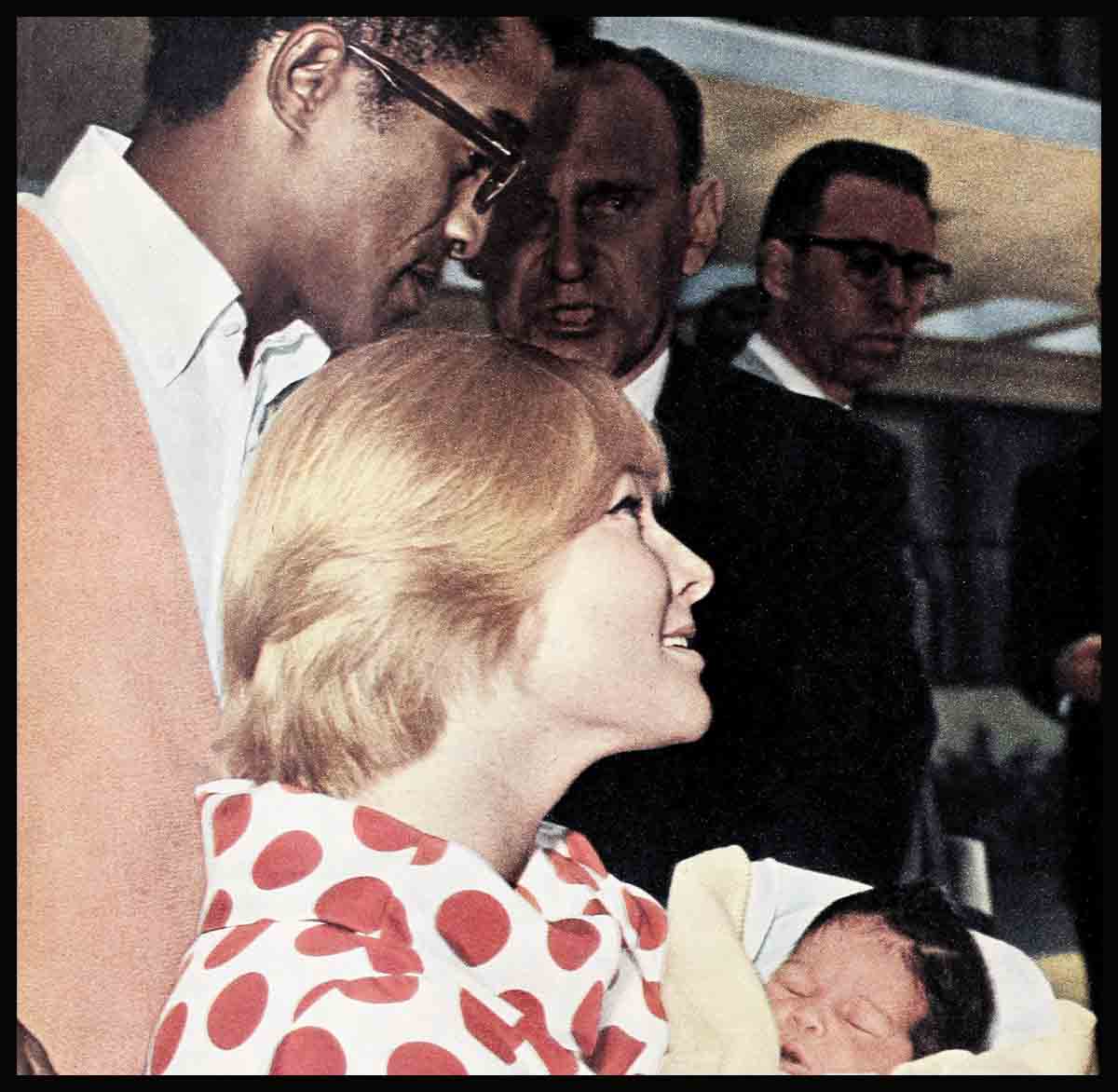

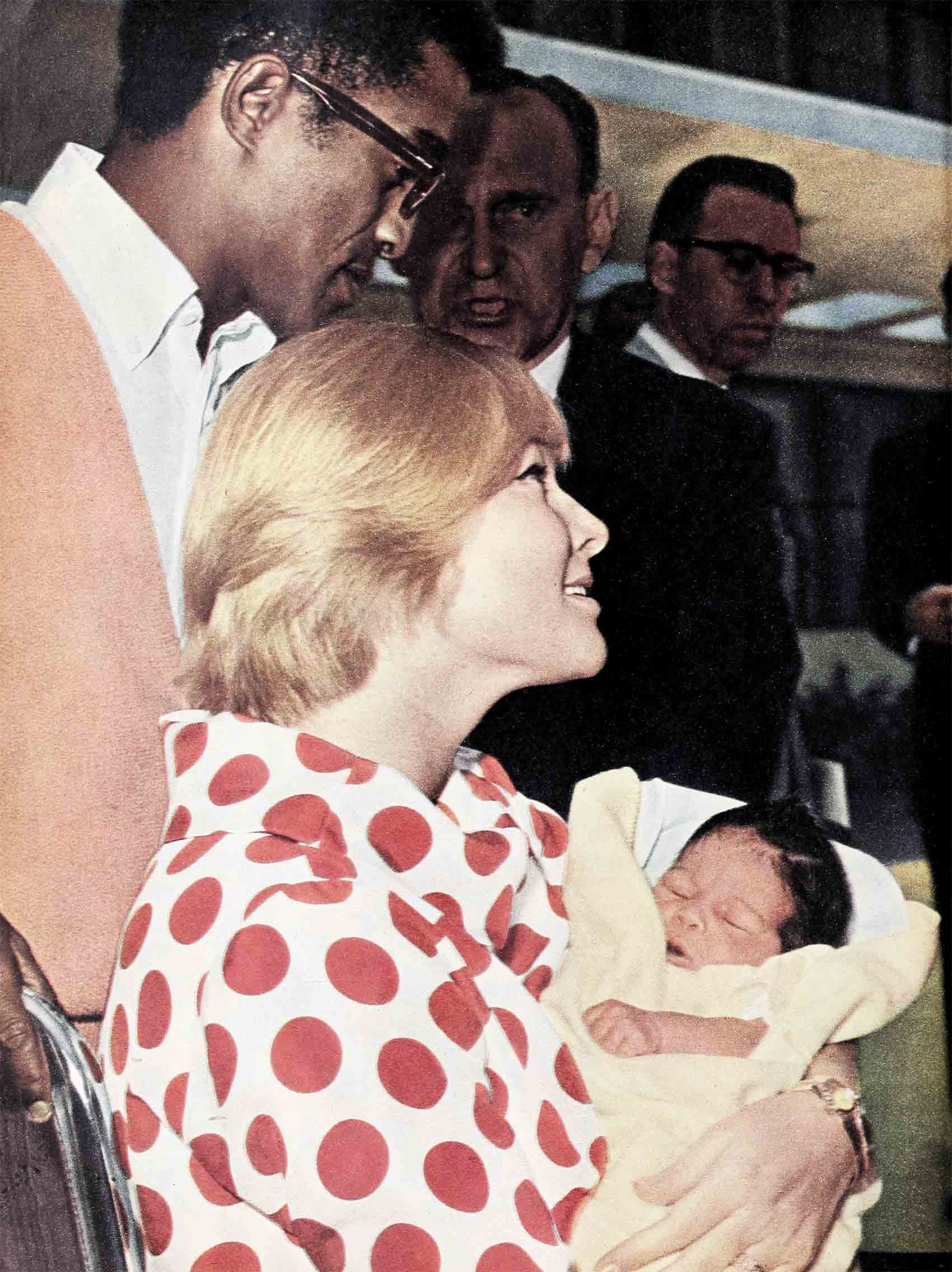

One of the presents Sammy took to Maybritt while she was in the hospital was a red and white polka-dotted dressing gown. It was an extension of a family joke. When news of Maybritt’s pregnancy had been printed, Sammy had told an interviewer, “I don’t care whether our kids are black, white or polka-dot—just as long as they say, ‘Yes, Daddy,’ to me.”

Critics had branded the comment bad taste, without pointing out that the question itself had been inexcusable. By kidding the painful incident, it was made bearable. So Sammy and Maybritt laughed, and when mother and daughter were dismissed from the hospital, Maybritt wore her polka-dotted dressing gown for all the world to see.

Taking a five-day-old baby home from the hospital is, particularly for first-time parents, a nerve-wracking task. Maybritt and Sammy had been instructed in sterile techniques: the bottles must be boiled twenty minutes, the formula must be prepared under sterile conditions.

The child’s head must be protected until the cranial cavity is closed by the maturing skull . . . the neck must be supported . . . the total infant must be kept out of drafts, away from pets, and safe from germy adults . . . no one must smoke in her presence, and no one was to hold her except her nurse and her parents.

It was impressed upon them that few organisms on earth are as helpless or fragile as a human baby.

When Sammy and Maybritt emerged from the hospital, the infant held snugly in a pink blanket in her mother’s arms, twenty newsmen and photographers rushed forward to snap pictures and ask questions.

What color were the baby’s eyes?

Blue, and almond-shaped, exactly like her mother’s.

What color was the baby’s skin?

Pink, like that of all newly-born citizens.

Did she have hair? What color?

A soft cap of light brown covered her beautifully shaped head.

What was her name?

Tracey Hillevi Davis. “Tracey” because they liked the name; “Hillevi” in honor of Maybritt’s mother.

After five minutes. Sammy pushed his way forward, saying. “Okay. fellas, take it easy. I know you’re all fathers and will understand. We’ve got to go home. You can quote me as saying this is the greatest thrill in the world.”

Incidentally. Sammy was not alone in his nervous excitement that day. A major Los Angeles paper burst forth with the headline, “Davis ‘in the clouds’ after seeing new son!” In the text. the child’s name was incorrectly recorded as “Tracy Hillary.”

The three Davises drove to their beautiful home above the Sunset Strip and Tracey was installed in her white and yellow nursery opposite her parents’ bedroom. The nursery door bears the label, ‘Tracey’s Room.’ On duty was the Caucasian nurse who will take Tracey through her years of babyhood—when she can persuade Tracey’s father and mother to relinquish the baby for a few moments.

Sammy had hung blue, red, green and yellow balloons across the master bedroom, and across the width of one wall was a white paper banner bearing the greeting. “Welcome Home, Mama and Tracey.”

In the bedroom, and throughout the house, were the presents sent to Tracey. There were silver baby spoons, silver porringers, silver cups, stuffed dogs, cats, and pandas; there were sweaters in half a dozen sizes, dresses, gold bracelets no larger than gypsy earrings, an add-a-pearl necklace. There were leather albums for her baby pictures, several pairs of ski boots and a pair of tiny snow shoes.

In the living room stood stacks of letters and telegrams of congratulation. Out of hundreds of such messages there were only six hate letters, and they came—not from he South—but from Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey.

Harry Belafonte called the next day. He has a three-year-old son, also a child of a mixed marriage. Sammy says, “We were just clowning around, but we talked of announcing Tracey’s engagement to Harry’s son. May says the age difference is about right. I think they’d make a very nice couple!”

That much of Tracey’s future settled, Sammy got out his camera and began to take pictures. Professionals agree that Sammy is a great photographer and could have become famous for his camera work, had he not gone the show business route.

“It’s up to the world”

Obviously, Tracey will be one of the most photographed of children, but, says Sammy, “There aren’t going to be many layouts of the baby. We don’t want cover pictures of Tracey. What we want is dignity, and dignity is the reason our marriage has survived and will continue to survive.”

And he says, “People ask how I’m going to raise my baby. We are going to raise her to be a normal little girl. Just a little girl. It’s up to the parents to see that the child remains a child in the home and is given the proper values in life. I don’t believe in saying to a child when it’s four or five years old, ‘Now, look, your mother is white and I’m Negro and you’re a mixture.’

“By that time the child should already have a concept of the love its parents have for the child and for each other. Our daughter, naturally, will be reared against a strong religious background, one May and I share. This will give her spiritual strength. After that, it’s up to us to give her the moral strength that comes from love and understanding.

“I’ll tell you something: I have seen the children of mixed marriages and usually, ninety percent of the time, they are beautiful. They get love and understanding beyond the usual, because the parents of such children have had to realize a greater love and understanding in the first place.

“A big difference in a mixed marriage is made by the economic factor. If you’re poor, you realize poverty is next to hatred. We are lucky in having enough financial security to prevent that. Because of our situation, Tracey will be exposed to the best we can give her of both races.

“As she grows up she will see the difference in the races of her father and mother. She will know I’m a good father and a good husband, and that May is a good mother and a good wife, and she’ll be able to see the great love we have between us.

“Protection can be given a child only to a certain degree, then you have to let her go on her own. We live in a changing world. It isn’t easy to bring up youngsters now, but from what I hear of history, it’s never been easy.

“Still, I hope the time will come when there will be no danger of a chum of Tracey’s suddenly turning on her and saying, ‘Your father is a nigger.’

“All children belong to the world, and the good and evil in it affect their lives. My baby belongs to the world, and what happens to my baby is up to the world.”

THE END

—BY JULIA CORBIN

Sammy Davis will soon be seen in United Artists’ production of “Soldiers 3.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

1 Ağustos 2023You got a very wonderful website, Glad I noticed it through yahoo.