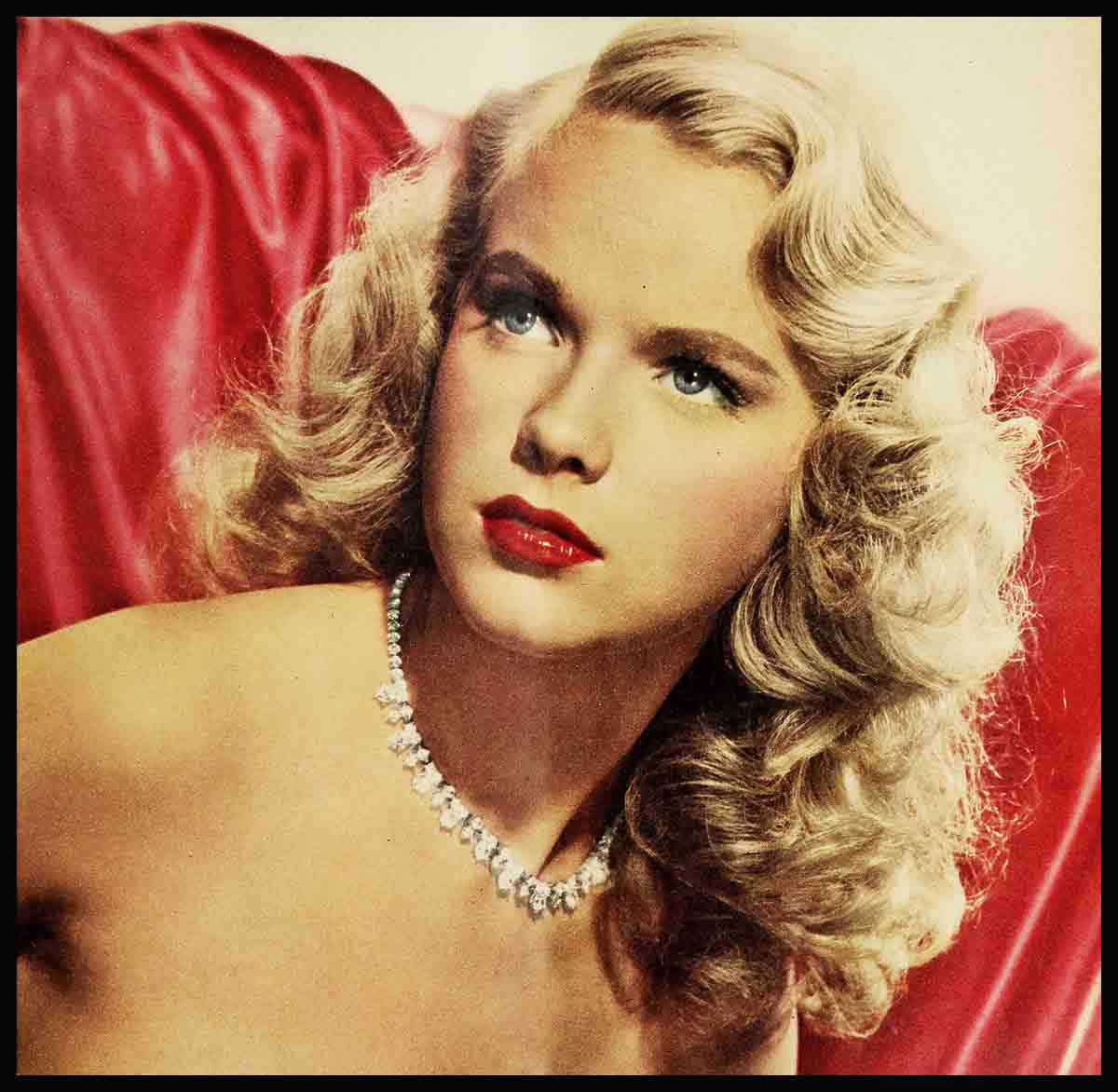

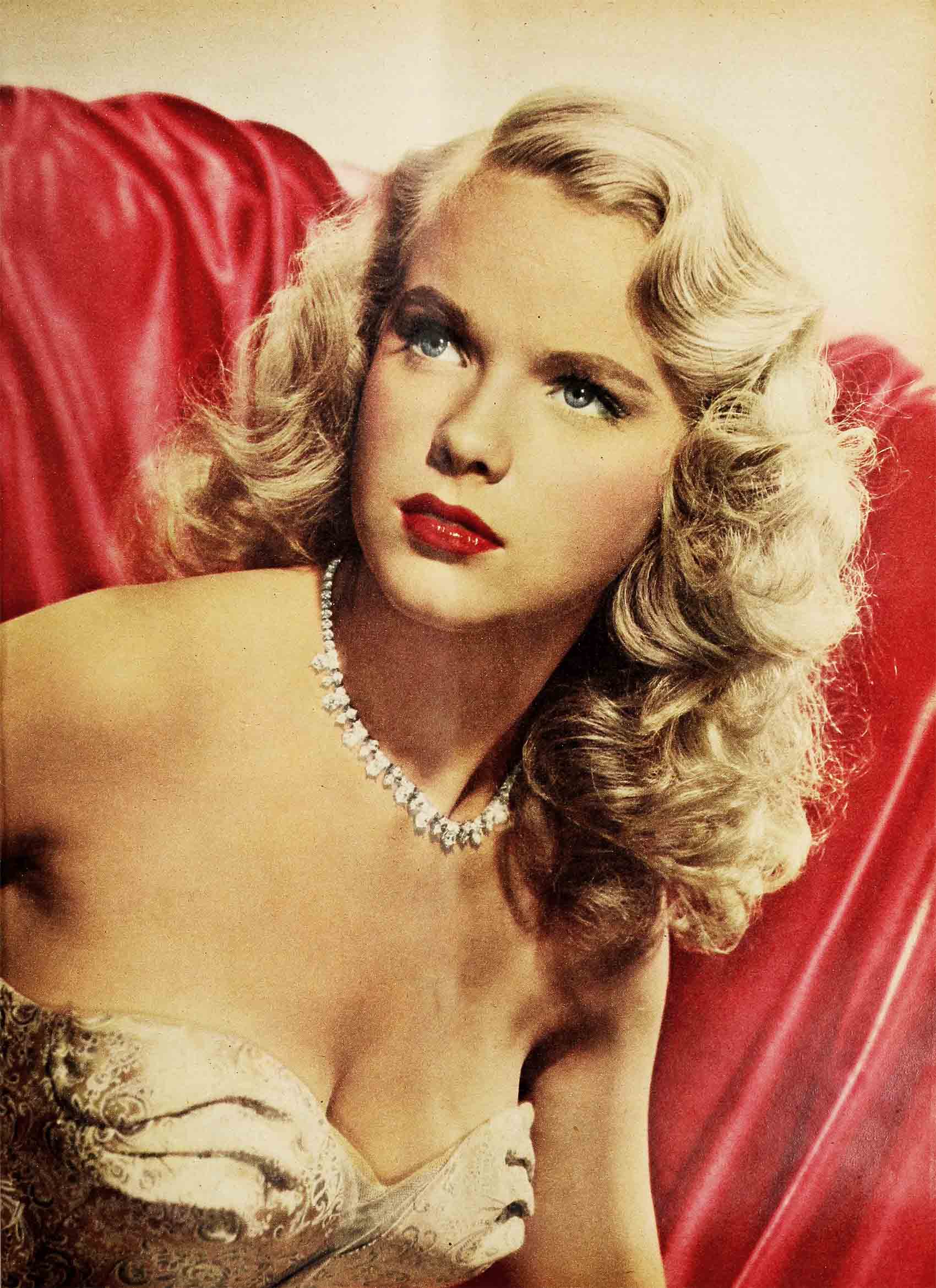

Married Madcaps—Anne Francis

In September of 1951 Anne. Francis took a wastebasket to the incinerator shared by tenants of her apartment house and started a fire that’s been burning ever since. For also at the incinerator, armed with his own rubbish, was a darkly handsome young man named Bamlet Lawrence Price.

“You go first,” said Anne. “You were here first.”

“Allow me,” said the young man, and gallantly dumped Anne’s milk bottle tops and Kleenex into the inferno, along with his own milk bottle tops and cardboard shirt stiffeners from the Chinese laundry.

During the short walk back to their mutual apartment building each recalled having met the other at a party not long before, and during the next few months they grew to know each other quite well. Bam dated Anne on Sundays and learned about her work in Dream Boat and Anne listened, enraptured to Bam’s accounts of his course in motion picture production at UCLA. In May of 1952, they began sharing the same wastebasket. The wedding was a complete surprise to everyone. Anne hadn’t mentioned to anyone that she was considering marriage, or was even in love for that matter. She had dated the usual bachelors about town but no one at her studio gave a second thought to Anne’s becoming a bride. She had been a professional actress since the first year of her life, and with only 21 birthdays behind her seemed quite willing to devote herself entirely to her work and to enjoying her new-found success in movies. And then on Friday, May 16th, she telephoned 20th Century-Fox and calmly announced that she was marrying Mr. Price the following day.

Anne is “different” in Hollywood in that she works with calm assurance and complete lack of temperament. In the three years she has been in town she has fulfilled the best hopes of the directors with whom she has worked, yet managed to live her own life, the kind of life, except for the hours in front of the camera, that might be lived by a small town girl at college.

Her wedding stayed in character. It was traditionally beautiful, quiet, and slightly crazy, but bare of crowds and flashbulbs. It took place in the chapel of the Harvard Military School, an institution in North Hollywood which Bam had attended in his youth. The presiding minister was a friend of Bam’s, and families of both the bride and groom flew into town from New York and Porterville, California, respectively. It should have gone off smoothly, but then, few weddings do. Anne’s father, preparatory to giving away his only daughter, was more nervous than a politician on election eve. “Why,” he kept growling, “doesn’t the organ start playing?”

He ignored the fact that Bam had not yet arrived, and for her part Anne was wondering, in a simmering sort of fashion, what Bam had been doing driving in the opposite direction as she and her father had approached the church. She calmed her own frazzled nerves by telling her father over and over that they were to use the lock step going down the aisle. She neglected to so inform her matron of honor who, as a result, eventually went trotting briskly toward the altar, leaving the bride and her father leagues behind. Bam finally arrived, having been there once before but having forgotten to pick up his best man. This had now been rectified, and the explanation for his driving away from the church ten minutes before the scheduled ceremony was gratefully accepted by Anne.

Secure in her knowledge that the groom was here and that her father knew all about the lock step, Anne went back to visit the pastor, who was just donning his robes for the ceremony. “He looks just wonderful in them, just beautiful,” she confided later to her father as the two of them stood waiting for the strains of Lohengrin. “Blast!” roared her father. “This isn’t his wedding! It’s your wedding! When is that infernal organ going to start?”

The tumult and the shouting and the wedding over with, the new Mr. and Mrs. Price left for a brief honeymoon in Yosemite and San Francisco and then returned to their two apartments. Each was quite small, consisting only of a living room, bath and kitchen, and they decided to keep both of them until a larger apartment was available. They lived in Anne’s, and Bam used his for his work.

Bam’s work must be explained in order to effectively chronicle the first months of the marriage. In his study of motion picture production he must turn out a thesis, which in this subject consists of a complete documentary film, written, produced, directed, photographed, edited, etc. by the student himself. Bam chose the subject of the evils of drug addiction, and when he first met Anne was in the throes of interviewing those unfortunates who had been

a slave to the habit. The project went on until shortly before Christmas of 1952, the last few months being devoted to the editing, or cutting, of the film. Luckily, Dream Boat was Anne’s last picture until she began her role of the swamp girl Flamingo in Warner Bros.’ A Lion In The Streets last December. As a result, she had seven full months in which to devote her time to assisting Bam. She was alternately his script girl, his assistant director, and his Girl Friday, and in helping her husband Anne learned more about what goes into making a movie than she had ever gleaned from her own work in front of the cameras. “I now adore all assistant directors,” she announces, “and don’t know how they ever keep their sanity.”

When the time came last August that a larger apartment was ready for occupancy, they were delighted, although the more Bohemian residents of their neighborhood were saddened by the news that henceforth the Prices would live in one apartment. “What a dee-vine arrangement!” several gay divorcées had clucked. “Twoapartments!” Anne merely smiled. To each his own, she figured, and for her there was only one living arrangement for a marriage—two people with one key.

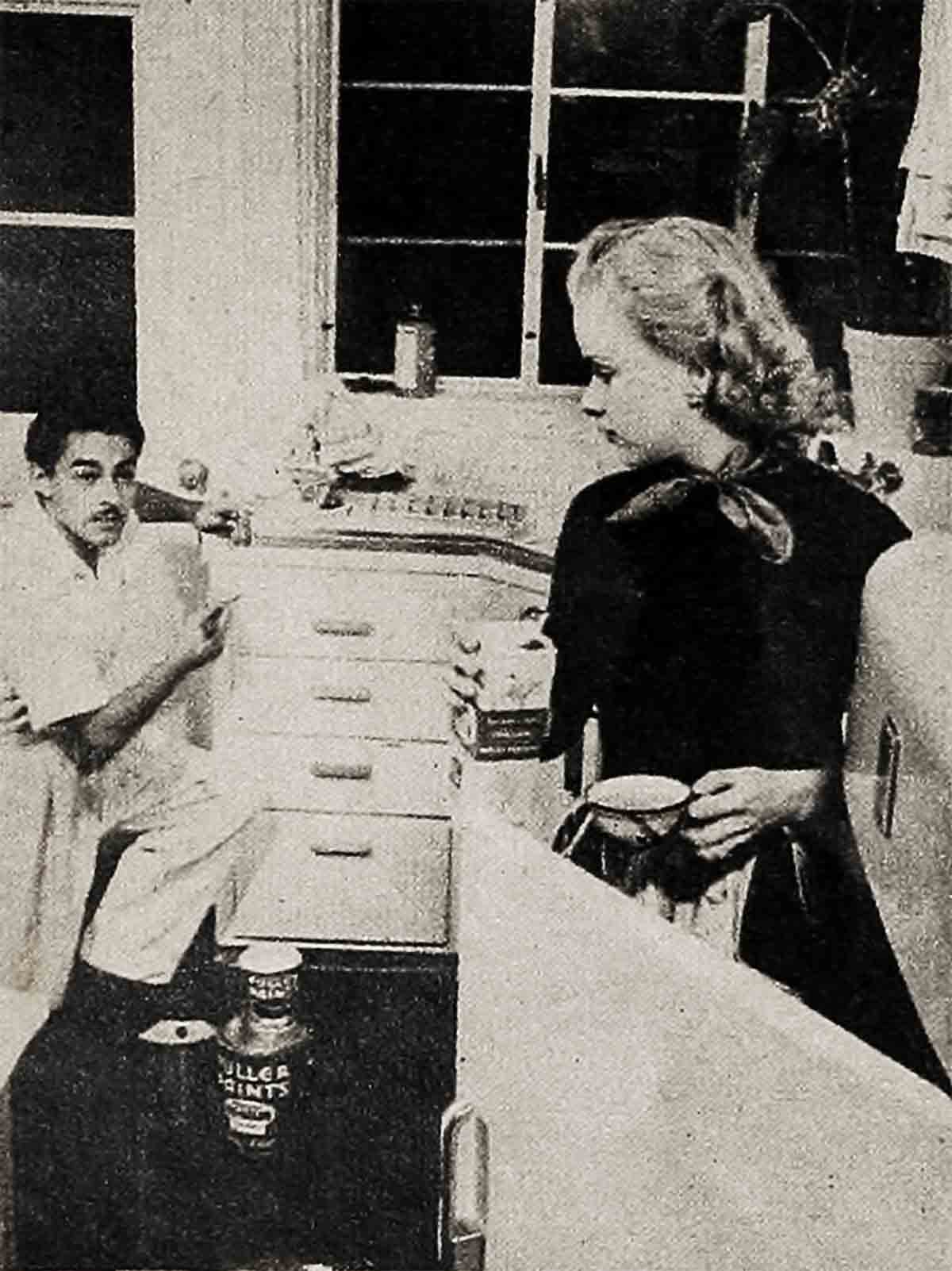

The new apartment gave them the feeling of great spaciousness. There was a living room, dinette, bedroom and kitchen and what’s more, the living room boasted a fireplace. At last, thought Anne, here was a real home. Moving day changed her thoughts somewhat. Bam filled the fireplace with cameras, tripods and batteries, and flashbulbs wandered here and there onto the hearthstone. His desk was put in the dinette and within two days he had strung wires from here to there throughout the room. These were promptly hung with strips of film, and when they put up a folding screen to hide the working room from the living room this, too, was shortly beribboned with film.

In the days when Bam was shooting his picture things were fairly neat. His day had begun at seven and he whisked out of the house with his cameras and came back later with nothing to show for his work but neat little spools of film. Last fall it became a different story. The cutting of film is the messiest part of the business, and soon after his morning coffee Bam disappeared behind the film bunting and didn’t emerge until dinnertime, when he appeared with bloodshot eyes.

“The only way I knew he was there,” says Anne, “was from the noise of the movieola. Or if he wasn’t working with that he had the radio turned on full blast.”

Once in a while she parted the curtain of film, feeling like Sadie Thompson making an entrance, and ventured in to look over his shoulder. A scene was running through the movieola, a small machine used by film editors. “Uh, uh,” Anne would say, shaking her head in a negative fashion. “That should be a closeup right there instead of a long shot.”

“You think so?” said Bam. “Then what about the closeup that comes just before that? Before the fadeout.”

“Now, wait a minute, wait a minute,” said Mrs. Price, putting her hands over her eyes. “I can see the whole thing clear as day. Now. If you put the closeup before the fadeout and then follow with the—follow with the—honey, I’m losing it. I’m all muddled. Goodbye.” And she parted the film curtain once more and left.

Anne didn’t often enter her producer’s den. As confused as it was Bam knew where to find every scrap he wanted, and as a result neither Anne nor the woman who comes once a week to clean dared to go near the cluttered desk. One day Anne stepped squarely on a closeup, neatly imprinting the film with the outline of her shoe, and she was so angry with herself that she went into the bedroom and sulked for an hour.

While Bam was thus engrossed Anne had time to attend to her own affairs. Those seven months of freedom gave her an opportunity to learn the difference between a broiler and an oven, and how to make dirt disappear from a house. They also gave her a free mind with which to struggle with the adjustments necessary in a new marriage. Despite her youth Anne has the intelligence to know that it takes work to make a good marriage. Most people, she figures, are dreamers. They think that falling in love is the whole answer and the end of all effort, but Anne knows that’s when the work begins.

The first thing she learned about was Bam’s tremendous energy. Anne had thought she was similarly endowed, but after a month of trying to keep up with his schedule she fell by the wayside. He was up at seven to start a 16-hour workday and Anne, who got up and made his breakfast and then worked all day by his side, was exhausted by nine P.M. It dawned on her finally that it would be more sensible to stay within her limits, a practice which in time made her a more cheerful bride.

Her next step was to worry about him. Nobody, she thought, should keep up such a killing pace, but she learned that it is Bam’s way, and that if she fretted about it and nagged him to work less, it would only make him unhappy. This premise was so settled in her mind that when she began work in A Lion InThe Streets and had to be up at 4 A.M. and at the studio by 5:30, she didn’t object when Bam too crawled out of bed and started his own day along with her. She could hear him whistling in the kitchen as he started the breakfast while she took her shower, and she knew that this was what he wanted to do, or he wouldn’t be doing it. She has contented herself merely with talking him into taking Sundays off. “You know, dear,” she said, “just to relax? Maybe take a drive out in the country or something?”

There was no problem with the toothpaste tube; they use different brands of toothpaste, so the argument never arose about whether it should be squeezed flat or rolled from the bottom. They are both prompt people and never have to wait for each other to dress, and each is so attentive to details that often they both try to pick up the laundry on the same day. But Anne hit a snag regarding neatness. In her bachelor days she had always tended to strew things slightly through the apartment, and now that she was married felt quite miffed when Bam left his sports coat on the bed, his bath towel over the door and yesterday’s shirt on the floor. She was even more miffed when she realized that her husband, without having said a word, was deliberately demonstrating to her how messy a home could look when its residents let things falls where they may. By now she hangs up her own things as well as his and the other day when he asked where his jacket was, she smiled through gritted teeth. “I hung it up, dear.” Then laughed out loud.

In the beginning, there was a budget, an idea, Anne hastily explains that stemmed exclusively from her husband. She hasn’t the slightest affinity for arithmetic and not only told him so but proceeded to prove it. They started off with a special budget book purchased from a stationer, and neatly penciled in at the head of each column the names of their miscellaneous expenses. Anne kept it up to date quite dutifully for two weeks and then discarded the idea as entirely too much trouble. “Putting down how much I spend for soap,” she told Bam, “can’t possibly increase our income or decrease our expenses. As far as I’m concerned the budget book is a big fat waste of time.”

Their bank statement arrives and stays for days on the same table, each waiting and hoping that the other will be a martyr and inspect it for possible errors. Up to this writing Bam has been the inevitable loser, and one day was foolish enough to attempt to explain to his bride how a bank statement should be checked. “You see,” he said, “you merely check the canceled checks with a check against each—” he turned around in his chair. Anne had disappeared. “Where are you?” he called. “I’m explaining how simple it is to do this thing!”

Her voice floated merrily from the kitchen. “I’m baking a pie,” she said. “This is something I can wrap my mind around.”

Anne indeed can master the mysteries of a kitchen and is rapidly becoming a culinary queen. Bam is no slouch himself and on Sundays, the only day they have time to sit leisurely over breakfast, his waffles alternate with Anne’s popovers.

They both wear white terrycloth fatigue outfits around the apartment, and other residents refer to them as the ghost couple. The neighbors have also had occasion to note that the young Mr. Price may possibly be out of his head. There for a few weeks he was frequently seen in the garden, leaping into the air and flailing his arms for no obvious reason. What Bam actually was doing was collecting food for his wife’s new pet, a green creature three feet long which Anne describes as “a friendly snake.” She had first become addicted to snakes back in Atlanta on a P.A. tour when one night she was standing in the wings of a theater and felt a light touch on her shoulder. Turning, she saw the head of a good sized serpent nestling on her upper arm. This particular snake was due to go on stage soon with his own act, and when editor Paul Jones of the leading Atlanta newspaper saw that Anne was not only unafraid but quite fascinated, he offered to send her a snake for a pet. Told it was impossible to adopt her newfound friend for her very own, she agreed to accept a substitute. “But be sure,” she told Jones, “that he is a friendly one.”

The wire arrived a few days after Anne’s return to Hollywood. “CURLY ARRIVING EIGHT MONDAY MORNING ON SUPER CHIEF COMPARTMENT SIX.” Arrived at the railroad depot on Monday, Anne looked up compartment six and found a pale and shaken newspaperwoman who held out to Anne, at arm’s length, an immense glass jar filled with Curly. “Here,” she said in a weak voice, “you take him. I haven’t been able to eat a thing since I boarded the train.”

Curly was taken home and given loving care. The neighborhood was nonplussed by Bam’s daily safari for a boxful of insects, and friends of the young couple did not take kindly to being met at the Prices’ front door by Bam wearing Curly in his hair or around his neck. All things must come to an end, however, and when Curly died a few weeks later everyone was quite jubilant, except Anne and Bam. They have concluded that it would be easier to raise something more along the human line and are hoping, after they eventually buy the house they are saving for, to start a family of their own.

Meanwhile their respective parents are delighted with the marriage. Bam’s mother and father came down to Hollywood last Thanksgiving, armed with candy and cookies and flowers, plus wood for the fireplace. The latter was stacked out. of sight for the bright day when the fireplace would be empty of camera equipment, and then, because the dinette was bursting with film, they all went for Thanksgiving dinner to the home of Bam’s friends in Whittier, 17 miles away. It was to this same house that last summer Anne and Bam decided to walk, and did. When the elder Prices heard about the jaunt they looked at each other and beamed. Wherever else would their son have found a girl who liked to walk as much as he does?

When Anne’s parents came west for Christmas, a fire was blazing in the fireplace and a dinette set sat where it ought to sit—in the dinette. They had a merry holiday and a fine dinner and when it was mentioned that Thanksgiving day had been spent with their friends in Whittier—the place 17 miles away where they had once walked—Mr. and Mrs. Francis caught each other’s eye across the table. Where else could Anne have found a boy who liked to walk as much as she does?

So although Anne and Bam can account for their finances only the first two weeks of their marriage, although he puts her through her paces in the matter of putting things away, although their first year was lived with a movie, and although Anne goes away from home and orders snakes delivered on her return, this one looks as though it’s going to last. He brings her flowers “for no special reason”, they completely understand each other’s work, and they like to walk like nobody else on earth. To top it all, Bam approves of her driving. “And,” says Anne proudly, “he told me that after we were married!”

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1953

No Comments