How Jacqueline Kennedy Gets On With Her In-Laws…

The White House—like most houses—has had its share of that most hair-raising problem of them all (war, revolutions and national defense notwithstanding): The In-Law Problem. Mary Todd Lincoln reportedly had several “kin whom Abe, despite his general kindliness, could not abide.” James Polk, an otherwise calm and patient man, is supposed to have once ordered a brother-in-law “off these premises, federal to some, and private to me.” They still gasp in Washington when long-suffering Eleanor Roosevelt’s problems with FDR’s incredibly possessive mother, Sara, are recalled. (One example—about Inaugural Day, 1933—from Alfred Steinberg’s Mrs. R: “Once inside the White House door for the special lunch before the customary parade, Franklin and Eleanor were now officially President and First Lady. However, Franklin looked uneasy. The answer was not hard to find. He had to take his lady’s arm and lead the procession to the dining room. The problem was Sara Delano Roosevelt, beaming with joy on this wonderful occasion. Franklin looked helplessly at Eleanor. Then he took his mother’s arm and the two walked first in the procession, with Eleanor walking behind.”) What do they say in Washington today about Jacqueline Kennedy’s relationship with her in-laws—the fabulous, remarkable, incredible, overpowering, clamorous, nearly a dozen-strong Kennedys? “Things could have been awful between Jackie and—as I call them—that in-law mob,” says one society gal, a good friend of Jackie’s, “—but they’ve turned out beautifully. For the First Lady, let’s say, the in-laws are an in-group. Jackie had her doubts about them at first; I don’t think that’s any secret. She was scared stiff of them at first-back in 1951 when Jack was courting her, when she first met them. Who wouldn’t have been scared? They were, after all, a very, very different kind of family than most of us have ever known . . .” Said reporter Harold H. Martin, in a Saturday Evening Post article written in the early ’50’s: “When an outsider threatens to thwart the ambitions of any of them, the whole Kennedy family forms a close-packed ring, horns lowered, like a herd of bison beset by wolves.”

Said one of the Kennedy girls, Eunice supposedly: “It seemed for a while as if none of us would ever get interested enough in anybody outside of the family—even to get married.”

Writes family friend James MacGregor Burns in his recently-published book John Kennedy: A Political Profile:“Although (at the time he was courting Jacqueline) Jack and the older of his sisters were now in their thirties, they still behaved like children out of school when they congregated together at Hyannisport. All the in-laws and in-laws-to-be. Jacqueline included, had to conform to the hard physical and mental pace.”

Said Jackie herself after a weekend date with Jack at Hyannisport: “Instead of playing tennis one day and going sailing the next, like other people, they start right out early in the morning and go through tennis, swimming, golf, touch football and everything else they can think of. Then at night they play parlor games. . . . It wears me out just to watch them. Sometimes, during Monopoly, I get so sleepy that I deliberately make a mistake to end the game. Does Jack mind? Not if I’m on the other side.”

Rules for visiting . . .

A story goes that one Friday night, a few minutes after she’d arrived at Hyannisport for the weekend. Jack’s father handed his travel-weary daughter-in-law-to-be a letter which a family friend named Dave Hackett had sent them. The letter was captioned: Rules for Visiting the Kennedys. The elder Kennedy thought it was vastly amusing, and he read it aloud to Jackie: “Prepare yourself by reading the Congressional Record, US News & World Report, Time, Newsweek, Fortune, The ‘ Nation, How to Play Sneaky Tennis and The Democratic Digest. Memorize at least three good jokes. Anticipate that each Kennedy will ask you what you think of another Kennedy’s a) dress, b) hairdo, c) backhand, d) latest public achievement. Be sure to answer ‘Terrific.’ This should get you through dinner. Now for the football field. It’s ‘touch,’ but it’s murder. If you don’t want to play, don’t come. If you do come, play, or you’ll be fed in the kitchen and nobody will speak to you. Don’t let the girls fool you. Even pregnant, they can make you look silly. If Harvard played touch, they’d be on the varsity. Above all, don’t suggest any plays, even if you played quarterback at school. The Kennedys have the signal-calling department sewed up, and all of them have A-pluses in leadership. If one of them makes a mistake, keep still. But don’t stand still. Run madly on every play, and make a lot of noise. Don’t appear to be having too much fun though. They’ll accuse you of not taking the game seriously enough. Don’t criticize the other team, either. It’s bound to be full of Kennedys, too, and the Kennedy’s don’t like that sort of thing. To become really popular you must show raw guts. To show raw guts, fall on your face now and then. Smash into the house once in a while, going after a pass. Laugh off a big hole torn in your best suit—or a twisted ankle. They like this. It shows you take the game as seriously as they do.”

Did Jackie find the letter amusing?

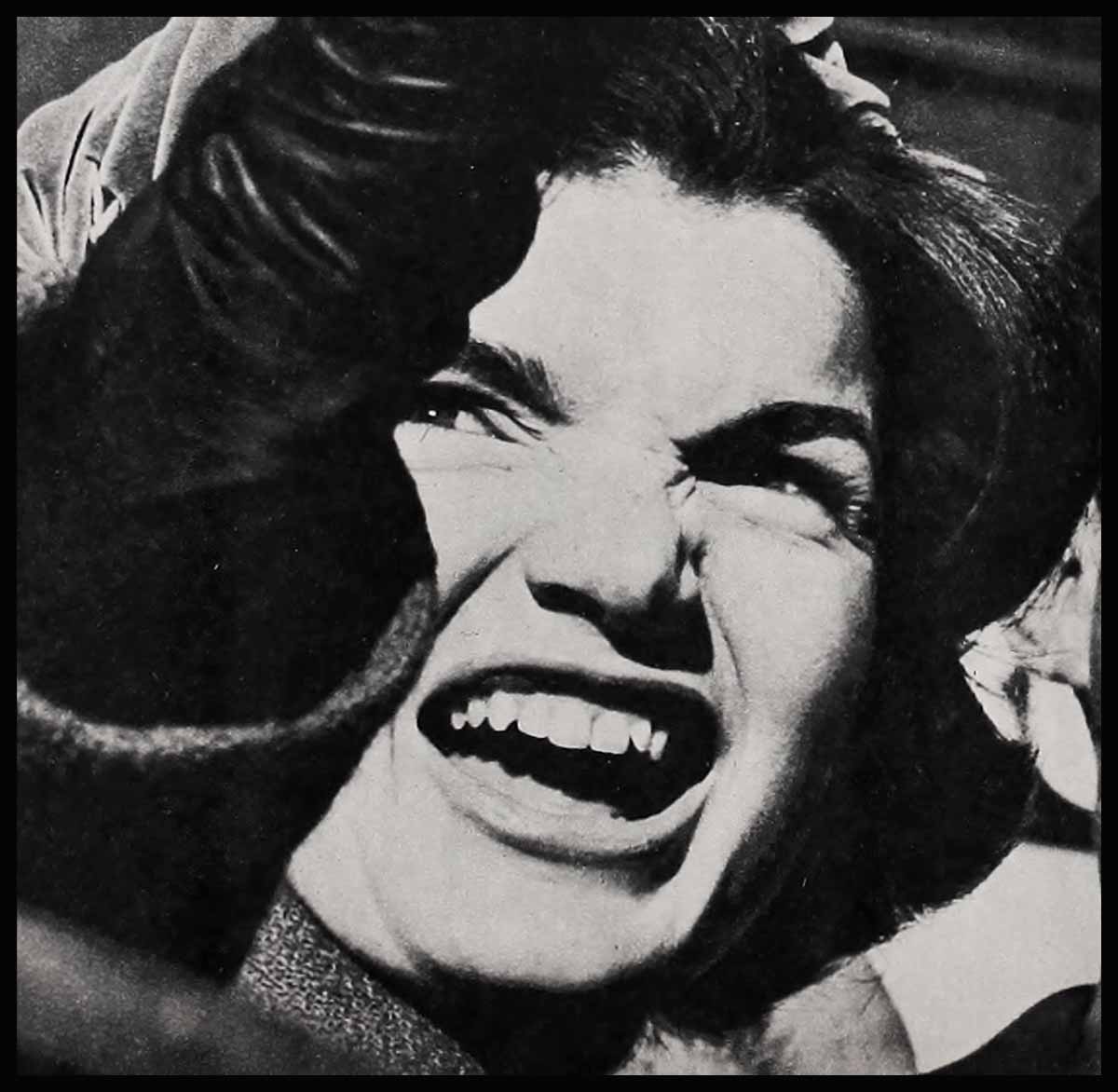

“Sort of, at the time,” says her Washington friend. “But only sort of. She still had a hard time getting used to this family and its ways. And she had a harder time getting used to the touch football routine. Once it even cost her a broken limb, poor thing. The family was outside the house playing the game one morning. They persuaded Jackie to join them. She did—and two minutes later she broke an ankle.”

That night, it’s said, Jackie decided that the time had come to assert her independence. At dinner—when someone asked her how her leg was getting on—she ignored all The Rules and softly answered that her ankle pained her “terribly” and that she was “through with football for good.”

Later that evening during a rare lull in family conversation, Jack turned to the unusually quiet Jackie and, smiling, asked: “A penny for your thoughts?”

Whereupon Jackie smiled back at Jack and—again softly, but loud enough for everyone in the room to hear—she said. “But they’re my thoughts, Jack, and they wouldn’t be my thoughts any more if I told them. Now would they?”

The lull in what had been conversation became dead silence now. The Kennedys all looked at one another, amazed. Then Joe, Sr. laughed suddenly and said something about liking “a girl with a mind of her own—a girl just like us.”

And the others laughed, too. Uproariously. A good loud Kennedy laugh.

And so—though Jacqueline Bouvier, soon-to-be Kennedy, would never quite become “just like us” and would prove herself, as the years passed, an independent spirit in her own right—the rapport between herself and “that mob of in-laws” was established.

“The rapport between them today,” says someone who should know, “is a lovely thing to witness. At its simplest, Jackie has come to adore the Kennedys, and they to adore her. I don’t know who her favorite of the group is. Jackie isn’t the kind of girl who would say. She knows some better than she knows others. But . . . well . . . if I had to guess, I would say that she loves Rose Kennedy, her mother-in-law, just a little bit more than the others. This is only natural, if you know Rose. . . .”

Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy

The daughter of a Boston politician, she went against her family’s wishes—they wanted her to marry a prominent middle-aged contractor—and she married instead a brash young upstart named Joseph Kennedy. In time, she would bear Joe Kennedy nine children. In time, she would glory in the success of several of them—but, too, she would suffer through the death of two of them (Joe, Jr., the oldest, who fell in World War II, and Kathleen, who was killed in a plane crash in 1948).

Jackie first heard mention of Rose Kennedy during one of her early dates with Jack, at a small dinner party, in Washington. The subject of mothers came up at one point, and—after a few of the other guests had made with the Freudian cracks and analyses—someone noted to Jack that his mother was an amazingly uncomplicated woman.

Jack nodded and said, “Yes. She’s that. Uncomplicated. And amazing. . . . But most of all she’s a terribly religious woman. Her faith in God, I think, is the most amazing thing about her.” He went on to say: “I remember . . . while she was always very close to us, she was, at the same time, a little removed when we were kids, and still is—which I think is the only way to survive when you have nine children. I thought she was a very model mother for a big family.”

A friend of the family told Jackie not long after, “I never saw a mother with such devotion to her children. When they had the house in Bronxville decorated by Elsie DeWolfe, Rose’s room was furnished with pieces that had a very beautiful but very delicate and fragile silk upholstery. Rose took one look at it and had it covered up immediately with rough, hard slip covers. She said the room was no good to her unless the smaller children could play in it with her. This great closeness that the Kennedys have as a family I think is entirely due to Rose. . . . But you’ll see what I mean, as time goes on, Jacqueline.”

Time did pass. Jackie got to know more and more about her mother-in-law. Part of what she must have learned about the character of the woman is perhaps best summed up by James MacGregor Burns, who has written: “What Rose Kennedy lacked in intellectual brilliance she made up in her intense love for her family. Love and a sense of duty were needed in the Kennedy home. The children were so numerous that she had to keep records of their vaccinations, illnesses, food problems and the like, on file cards. But she was still able to give each child some individual attention. Somehow she survived and even thrived, keeping her face unlined and her figure as modish as ever. Years later, on meeting this mother of nine still looking so young, a gallant gentleman took her hand and exclaimed, ‘At last—I believe in the stork!’

She led the table talk

“In her husband’s absence, she would even work up current-events topics and guide the discussion of them by the children at the table—her husband would have expected that. With him away so often and for so long, the daily routine, despite household help, was not simple—certainly not so easy as it later seemed to some.”

The story is told that Rose Kennedy’s greatest delight in life are her grandchildren, of whom she has hordes; that one of the most tragic days in her life was the day in 1954 when Jackie suffered a miscarriage and lost her first child.

Jack, recuperating from a grinding political tour, was with his father and brother Bob at the family’s Riviera villa. Jackie’s mother, stepfather and sister Lee were also in Europe at the time.

“On hearing the news about Jacqueline and the baby,” says a friend, “Rose—who was in Boston, visiting some relatives—wept for a little while. Then prayed for a little while. And then, suddenly, she said, ‘Good heavens, what am I doing here being so sorry for myself when that poor girl is lying there all alone?’ And she got into her car, drove to Newport, Rhode Island, and the hospital there; and for the next two days she barely left her daughter-in-law; she sat with her, comforted her.”

Joseph Kennedy

If Jackie was somewhat awed—and even frightened—by Jack’s father when she first met him, no one could possibly have blamed her. Despite his relatively humble beginnings (son of a Boston saloon-keeper turned politician) Joe Kennedy was—by the time he first shook Jackie’s hand and said hello to her that day in 1951—former Ambassador to England, former confidante of FDR, former movie producer, former bank president, former chairman of the Securities Exchange Commission and a man whose personal fortune was conservatively estimated at $250-million.

Though she’d heard from others that he was a man of great wit (He fractured the English once when, after making a hole-in-one in golf, he said to reporters: “I am much happier being the father of nine children and making a hole-in-one than I would be as the father of one child making a hole-in-nine”) ; though she’d heard that he was a man of unusual, if somewhat aggressive, charm (He once told the wife of George VI that she was a “cute little trick” and the Queen replied that she was “pleased beyond words”); though she’d heard that he was a warm and wonderful husband to Rose Kennedy (“Without my wife,” he’d once said, “none of us would have amounted to a thing, believe me”)—still, Jackie reportedly found it hard, at first, to warm up to the man.

But Jackie didn’t stay frightened for long. Because, the story goes, one day shortly after her marriage to Jack, while tidying up her husband’s study—Jackie came across an old folder, marked Letters from my Father. And in sudden curiosity, she found herself beginning to read.

One message which Jackie read was a cable, dated June 1940, and sent from the Ambassador’s office in London on the occasion of Jack’s graduation from Harvard. It read: “DEAR SON, MOTHER NOTIFIES ME THAT YOU ARE GRADUATING CUM LAUDE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AND RECEIVED MAGNA CUM LAUDE ON YOUR THESIS. I AM SORRY THAT THE WAR HERE IN EUROPE PREVENTS ME FROM ATTENDING TODAY BUT I SEND MY PRIDE AND BLESSINGS TO YOU ANYWAY. TWO THINGS I ALWAYS KNEW ABOUT YOU, ONE THAT YOU ARE SMART AND TWO THAT YOU ARE A SWELL GUY. LOVE, DAD.”

A letter, again from London—this one dated 1941—referred to a book titled Why England Slept, recently published and written by the then twenty-four-year-old Jack Kennedy. It read: “I am very proud of you, my boy, and of the excellent reviews your book has been getting. You would be surprised how a book that really makes the grade with high-class people stands you in good stead for years to come. I remember that in the report you are asked to make after twenty-five years to the Committee at Harvard, one of the questions is: ‘What books have you written?’ And there is no doubt that you will have done yourself a great deal of good. I am sending copies of the book to Professor Laski, to Churchill and to the Queen. I am sure they will all find it as excellent and interesting as did . . . Your Dad.”

Jackie read next a short note to Jack from his father—this one mailed from Paris, and dated 1937. It read: “You will learn soon from our lawyers that I have fixed separate trust funds on you and the rest of your brothers and sisters, each one amounting to well over a million dollars. I have done this so that you or any other of my children, financially speaking, can look me in the eye and tell me to go to hell. Also, there is now nothing to prevent any of you from becoming rich idle bums if you should want to. I trust that you won’t. But you are all now on your own.”

Finally, Jackie read two letters, both dated 1936. One was from Jack to his father, written from Choate—a New England prep school Jack was attending at the time. It read, in part: “My pal Le Mayne (Billings) and I realize we haven’t been doing such good work recently and we have definitely decided to stop fooling around. I really do realize. Dad, how important it is that I get a good job done this year. I really feel, now that I think it over, that I have been bluffing myself about how much real work I have been doing.”

The answer, from Jack’s father—in Washington at the time, working on a special job for the government—read: “I found great satisfaction in reading your letter, Jack, especially to find a forthrightness and directness that you are usually lacking. . . . Now Jack, I don’t want to give the impression that I am a nagger, for goodness knows I think that is the worst thing any parent can be. After long experience in sizing up people I definitely know you have the goods and you can go a long way. Now aren’t you foolish not to get all there is out of what God has given I you? . . . After all, I would be lacking even as a friend if I did not urge you to take advantage of the qualities you have. It is very difficult to make up fundamentals that you have neglected when you were very I young and that is why I am always urging you to do the best you can. I am not expecting too much and I will not be disappointed if you don’t turn out to be a real genius, but I think you can be a really worthwhile citizen with good judgment and good understanding.”

The letter went on and on; four or five more pages, as Jackie recalls. And, ret calls a friend of Jackie’s, “After she finished reading it, she found herself picking up a phone, calling Jack’s office at the Senate Building, and telling her stunned husband, simply: “You know, Darling, you have a wonderful father.”

“The rest—between Jacqueline and Joe Kennedy—came easy after that.”

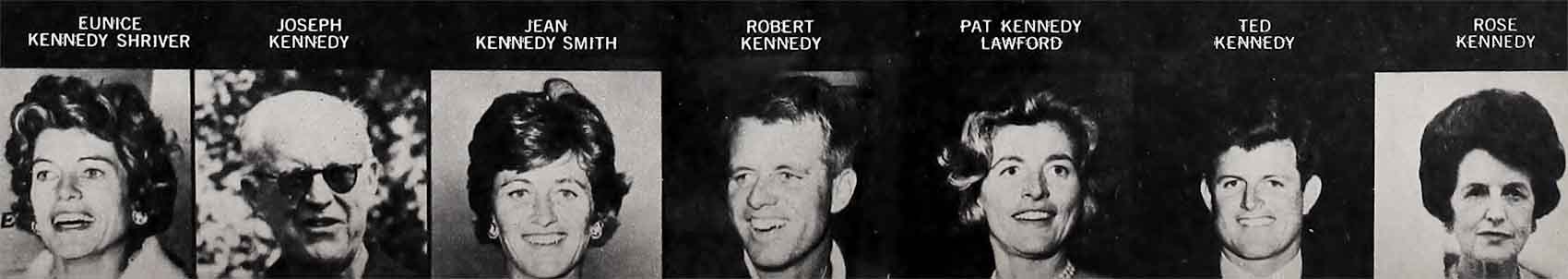

Of all the Kennedy girls, it’s been said that Jackie knows Rosemary and Pat the least and Eunice the best; with Jean running a close second to Eunice.

Of all the girls—according to one observer—“Rosemary, closest in age to her brother Jack, was a sweet, rather withdrawn girl, not up to the children’s competitive life.” After college, Rosemary attended a special teachers’ school and then left for St. Coletta, a Catholic school near Milwaukee, where to this day she has helped care for mentally-retarded children. Says a family friend: “She comes home rarely, she sees the others rarely. She has been at Hyannisport a few weekends when Jacqueline has been there, and from what I could see the two women got along nicely, walking along the beach together and indulging in quiet conversation.”

Chances are Jackie would know Patricia Kennedy (Mrs. Peter Lawford) better if Pat, as the wife of a TV and movie star, didn’t spend most of her time in Hollywood. “And,” as someone has said, “their lives are miles apart. . . . To the glamorous-enough Jackie, Pat seems to be an ultra-glamorous figure—a vividly romantic girl who turned down Lawford’s proposal of marriage with an I-don’t-know-yet, took off immediately after on a world cruise, changed her mind midway in Tokyo, cabled her family about her intentions concerning Lawford, laughed cheerfully at her father’s typically Irish-American reaction (“The only thing worse than marrying an actor, is to have you marry an English actor”) and then took off for the States and for Lawford’s arms.”

Those Kennedy Girls

Jean Kennedy (Mrs. Stephen Smith)—the youngest of the Kennedy girls—has been described as the “cheeriest of the bunch” and is reportedly a constant feather to Jackie’s funnybone. With remarks like: “The trouble with being a Kennedy is that people always mix us up. Women are continually asking me how it feels to be married to Peter Lawford—or what do I really think about the Peace Corps!” Remarks like: “It was a howl. Steve and I and the kids decided to go to Puerto Rico after the Inauguration. For a three-hour jet flight we figured, ‘Who needs to go First Class? We’ll go Tourist.’ So we arrived in San Juan, and what happened? There was a reception committee standing at the head of the First Class ramp—flowers, ribbons, everything. As we got off the plane, Steve and I stood on the Tourist ramp for a minute and wondered who the big celebrity on board the plane had been. Later we found out it had been me—the President’s kid sister!” . . . With stories like: the time she and Jack spent part of their Christmas vacation alone at the family’s Palm Springs house. She must have been seven and Jack sixteen. “And,” Jean said, “he was just a horror to be with. I remember one night my father phoned from New York and asked me how everything was going. I told him that I’d seen Jack kiss a girl named Betty Young under the mistletoe down in the front hall the night before, and how I thought that was just awful. I also snitched that Jack had had a temperature of 102° one night and that Miss Cahill, our housekeeper, couldn’t make him mind; that he ran out of the house to go driving with some of his friends. My father,” said Jean, “asked me, very seriously, what I thought about all this mischief on Jack’s part. And I thought for a moment, and then I said, ‘I suggest. Daddy, that you get right down here and give him one whale of a spanking!’ ” . . . Said a friend who witnessed Jackie’s reaction to that story: “I have seen Jackie Kennedy laugh before. Always little more than a smile, however, a twinkle of the eyes. But this night I saw her really laugh—break up. Pretty darn good family going, I say, when one sister-in-law can have that effect on another . . . don’t you think?”

Of all her sisters-in-law, however, the one to whom Jackie seems to be closest is Eunice Kennedy (Mrs. Sargent Shriver) . Eunice is, first of all, a basically sober girl, as is Jackie. Writes Joe McCarthy in his book The Remarkable Kennedys, “Eunice is the most serious-minded of the Kennedy girls. A friend of the family recalls that in her college days she would whip out a notebook and pencil and jot down notes when a guest at the dinner table said something that interested her. She is at the same time, in contrast with this seriousness, the most casual of the girls; says a friend, “Every time I’ve seen Eunice at Hyannnisport she’s been wearing her brothers’ sneakers.”

The two women got to know each other—really well—in Washington, back in the early ’50s, at the time of Jackie’s engagement to Jack. Jackie was working then as an inquiring photographer for the Washington Post and Times Herald. Eunice, a former social service worker in Chicago for the House of the Good Shepherd, was now working as executive secretary of the Justice Department’s juvenile delinquency section. Unmarried at the time, she lived with her bachelor Senator brother. Jack. She was the perfect person to fill Jackie in on the so-called little things about her husband-to-be.

“About dinner—to really make Jack happy, start with a good homemade soup. Then a roast—never overdone—and fresh vegetables in season. Perhaps, too, a potato or noodle casserole—Jack loves these.

A thinking man forgets

“About his absent-mindedness—don’t fret. It’s just a part of Jack. I’ve seen him leave once for the Senate in his old khaki pants. Sometimes his tie was spotted and his shirt-tail hung out. . . . He’s not being affected when he does things like this. It’s just that he has a great mind for big things, and when he’s thinking big things . . . he seems to forget completely about the lesser things.

“And Jackie, after you’re married, don’t he surprised if you come home from shopping some afternoon to find a delegation from Massachusetts waiting in your living room for your husband. He’s always inviting people over. Sometimes—don’t be shocked—he’ll even ask them to dinner.

“And if sometimes you expect to find him home late of an afternoon and George, his valet, tells you that Jack is down the street playing football with some of the neighborhood kids—don’t be surprised. He does that once or twice a week.”

And so it went—the sister talking to and advising the sister-in-law-to-be. And so the friendship between them grew. Culminating, it seems, one night in 1960, during the Presidential election campaign.

As Deane and David Heller tell it in their book, Jacqueline Kennedy: “At one particular rally in Wisconsin, it was bitter cold. There was snow all over the place. The Senator himself was late arriving. Jackie Kennedy and Jack’s sister, Eunice, had to fill in for him. There was a big crowd around, but the cold made them impatient. Something had to be done in a hurry if a large part of the crowd wasn’t to melt away before Jack Kennedy arrived. So the girls took over. They made impromptu speeches and Jackie Kennedy told the crowd: ‘I hope all of you will vote for my husband.’ It wasn’t long before she had them all in a good mood. During one lull in the long wait, Jackie called out over the microphone: ‘Doesn’t anybody want to sing or do a tap dance?’ That got a laugh. Somehow, Jackie and Eunice managed to keep the crowd happy—and kept them from leaving. When Senator Kennedy arrived, mushing through the snow, it was a very successful rally. It sure wouldn’t have been if it hadn’t been for the girls”—the two friends.

The Kennedy Boys

Jackie reportedly was not too sure about her feelings concerning Jack’s brother Bob when she first met him. While there was no question about his being a brilliant young man, his what-seemed-to-be abnormal ebullience—“He was the one who was always instigating those touch football games, for one thing,” a friend has said—is said to have made Jackie squirm on more than one occasion. Added to his own ebullience was an equally-ebullient wife, the very pretty Ethel Skakel Kennedy—a champion swimmer and horsewoman before her marriage and a gal who “just loved that touch football”; a seemingly indefatigable gal who had borne four children at the time of her first meeting with Jackie (with three more to come over the next few years) ; a gal whose happy household included, aside from husband and kids, assorted horses, cats, dogs, geese and even a pet seal which the family kept in a big swimming pool next to their house—and, well, let’s say that Jackie just wasn’t too sure at the beginning.

But—again—time passed, and with Ethel, the rapport was soon established. “She’s an absolutely charming girl,” a friend of both has said, “and more than that, she’s a magnificent mother. Jacqueline realized these things. And the friendship has grown over the years. . . . It’s not at all uncommon today to see the two of them together, at the White House—Bobby (now Attorney General of the United States) and Jack in the room next door talking politics, politics, politics—and their two wives, just a door away, talking children, recipes and clothes.”

With Bobby, the rapport took only slightly longer to get started; coming about, it seems, in late 1952—at the time Jack was campaigning for the Senate. Jackie, it’s said, was extremely impressed—and touched—by the devotion on the part of a kid brother who worked so hard, sweated so much, gave his all for an older brother’s success.

One night during the Senate campaign, with every available Kennedy off somewhere busy doing something or other, Bob was called from his office on extremely short notice to deliver a speech for Jack.

The speech—according to political historians the shortest on record—went: “My brother Jack couldn’t be here, my mother couldn’t be here, my sister Eunice couldn’t be here, my sister Pat couldn’t be here, my sister Jean couldn’t be here, but if my brother Jack were here, he’d tell you Lodge has a very bad voting record. Now I’ve got to get back to our office. Thank you.” Period. End of speech.

“Jacqueline,” says a friend, “tells that story often. She tells it with relish. She tells it, aside from with humor, with appreciation. Yes, I think you could say she likes her brother-in-law Bob. Likes him very, very much.”

That Jackie has always liked Teddy very very much, there’s little doubt. Described by James MacGregor Burns as “the youngest, and considered by many the handsomest and friendliest of the three boys,” it was Ted who — back in those dark days of winter, 1954-1955, when Jack lay near death following the serious spinal operations—sat with his sister-in-law in that little fourth-floor room adjoining Jack’s at the Manhattan Hospital for Special Surgery and made the long hours go by so much less desperately.

As so-called “family sentimentalist,” Ted has a warehouse of family stories at his fingertips, and he went through all of them for Jackie—stories about “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, his maternal grandfather; Patrick Kennedy, his paternal grandfather; stories about his mom and dad and when they courted; stories about old-time Boston elections—and, as Jackie recalled later, “He even got me to laugh a little with those funny stories of his.”

The day, however, for which Jackie will never forget Teddy had nothing to do with a funny story.

The day was February 7, 1955. Doctors had just performed the second operation on Jack’s spine, and one of the doctors had suggested that a priest be called to administer last rites.

Word of this got around New York fast. And soon, reporters from every newspaper in town were at the hospital. Most of them waited in the downstairs lobby for further developments. Except for one reporter, who got into an elevator, rode up to the fourth floor, spotted Jackie and Ted and, rushing over to Jackie, asked, “Mrs. Kennedy, is it true your husband’s dying?”

Jackie tried to say something. But she couldn’t talk.

“My brother’s darn sick”

Teddy talked, though. He looked the newspaperman square in the eye and he said, “Look . . . my brother’s darn sick. That’s all. But he’s going to pull through. You wait and see. His name’s Jack Kennedy—Kennedy—and he’s going to pull through! You understand that? Do you understand?”

Recalls a doctor who was present at the time: “When he was finished talking, Ted too had tears in his eyes. But he didn’t break down and bawl. Not young Kennedy. Instead he took the Senator’s wife’s hand and he began to lead her away. And as he did, she looked up at him—at this young, then very young, man. And the expression in her eyes was one of pure love. For what he had said. For what he had done. For how he had helped her, in this, her most trying hour.”

Said a friend of Jackie’s recently, recalling the same incident: “When she told me about it, years later, I said to Jacqueline, ‘Ted certainly sounds like a pretty wonderful boy.’

“She said to me, ‘Why shouldn’t he be? He comes from a pretty wonderful family. . . .’ ”

THE END

—BY ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote.PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1962