He Got Out From Behind The Ball

For Jeff Hunter. the search had only begun.

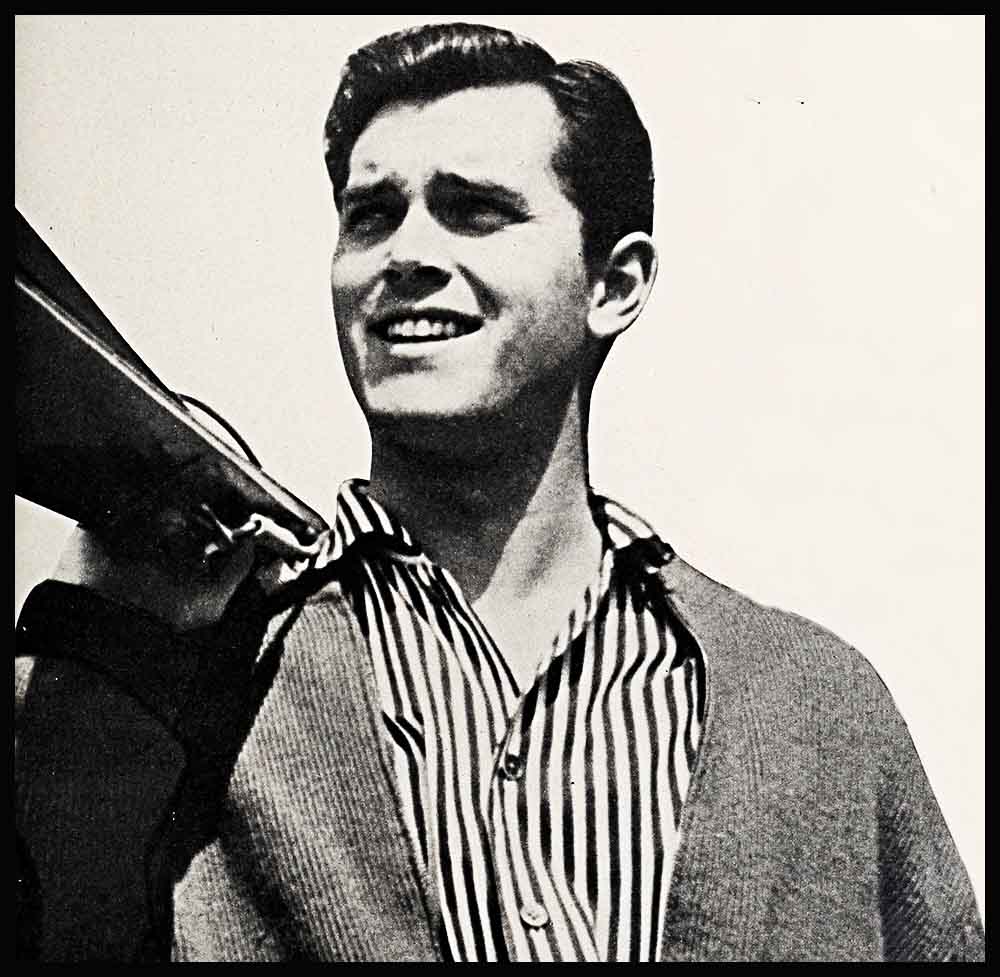

A journey to nowhere—that’s what it must have seemed to the handsome young star that night, almost two years ago, in Durango, Mexico.

In his motel room, Jeff packed his bags, wearily wondering where he had failed, and why. From next door, the jukebox in the cantina was flooding the air with Spanish love songs, and from somewhere across the September night there echoed the soft strum of a guitar.

But the night held no romance for Jeff. Not too long before, the beautiful girl who had been his wife had told him their marriage was through.

AUDIO BOOK

Now he had finished making “The White Feather,” and he was going home. But not to “the early Byrd house” he and Barbara Rush had saved for so long to buy. That was no longer his home. And their sturdy little boy. Chris—who held his father’s heart in his little hand—would be with him only half of his waking hours from now on.

Hollywood had tabbed Jeff’s and Barbara’s the “perfect marriage” and had predicted a brilliant career for Jeff. All his life, in fact, he had been voted the boy most likely to succeed. His home town had summed it up on an achievement plaque they’d presented to him, forecasting, “Future—Unlimited.”

Now Jeff Hunter was flying back to face that future. There was no marriage, no brilliant career, not even any pictures scheduled for him. It was ceiling zero—all the way around.

He wondered what his life would have been like if he had remained Henry McKinnies and become the college professor he’d once planned to be. And he wondered what Jeff Hunter’s life would be like from now on. What now?

Life had never conditioned him for failure in any way. Life had always been his friend, welcoming him with all its warmth and smiles. And Jeff had always given back the same—living and working and loving with full trust and sincerity.

Those dearest to him had also expected the ultimate from their only son. “I always expected perfection from Hank,” says his mother, Edith McKinnies, a wise and charming woman. “But I wasn’t conscious of this at the time. What mothers are? Naturally, I wouldn’t do it again. It isn’t fair, and I’m sure it put too great a strain on him.”

Yet, the habit of doing all that was expected of him, having the strength to measure up to their faith, was to prove vital later, when Jeff was grasping for happiness and still greater success.

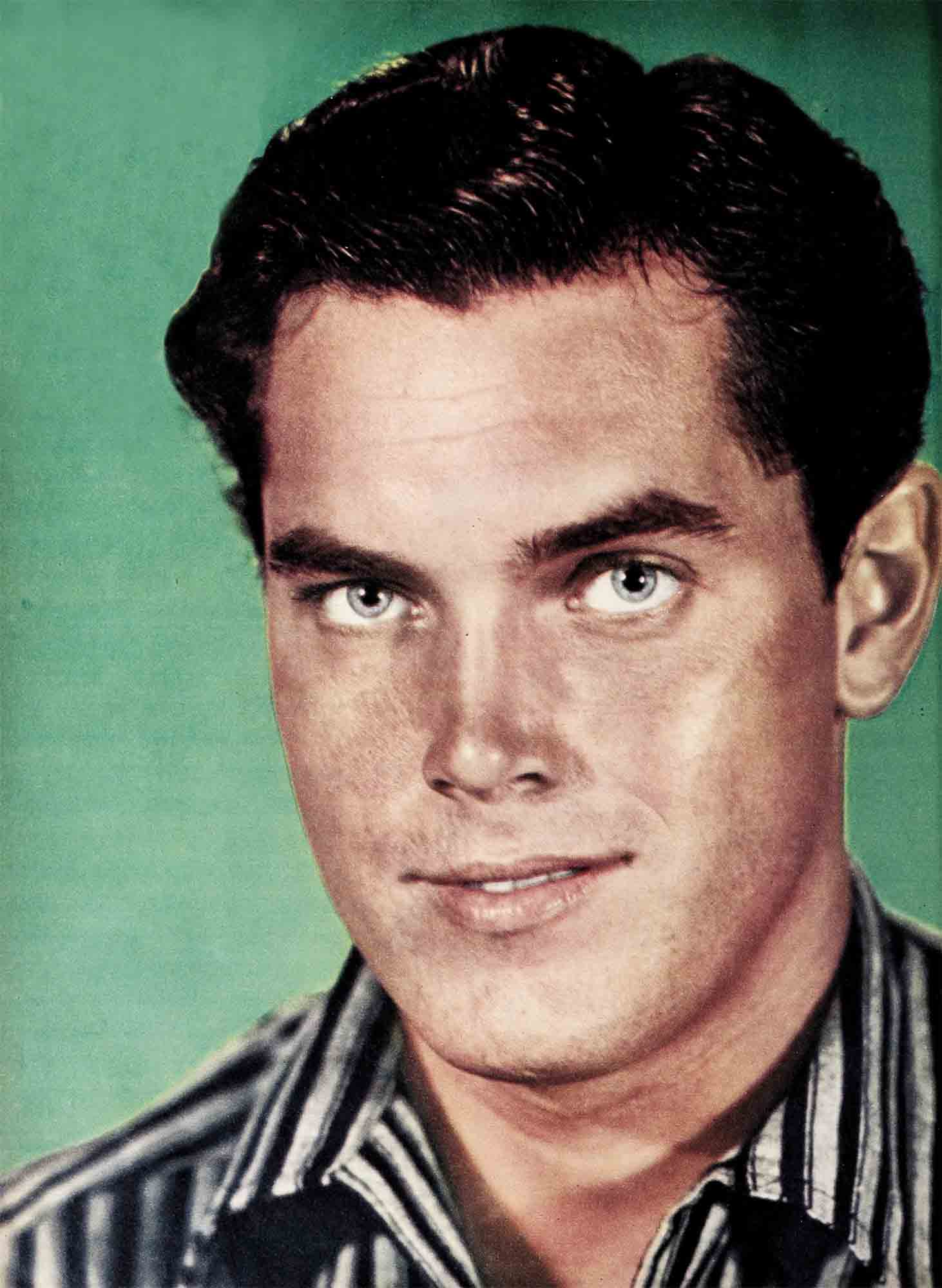

Success, in every form, had always seemed inevitable and easy to come by from the hour he was born. As a baby, he had the bluest eyes and the biggest smile of any in New Orleans’ Jefferson Parish. He was christened Henry McKinnies, Jr., and nicknamed Hank. His happiest New Orleans memory dates back to when he was four and, dressed in a clown suit, stood on Canal Street, holding tight to his mother’s hand and watching the Mardi Gras parade.

Through ability—and likability—Hank McKinnies was destined early to lead his own parade. Never, however, from any sense of fevered dedication. Just by constantly doing his best, as a scholar, artist and athlete. Later on, this was to puzzle other actors; they couldn’t understand how he could be so well-adjusted and be an actor. Nor could they understand why he wanted to act, since he had none of their own fevered approach. As a friend in one summer stock company put it, “Hank, you’ll never make an actor. You’re just too darn normal.”

But this was his goal—to be a well-rounded success; to excel in all he tried; to be liked by all he met; to measure up in every way humanly possible.

And his parents gave him every assist. He knew only harmony at home. As Jeff says today, “I was blessed; my parents are two very devoted people.” For his mother, a former English instructor, and for Henry, Sr., sales engineer for industrial refrigeration, life centered around their son.

“Hank always had some project going, and his dad was always helping him,” his mother recalls now. One year his father, whose hobby is miniature trains, made him a real sharp boy-sized locomotive, complete with a motor and two passenger cars. It seated six children, and it was always filled. When the church had an outdoor fair, Hank raised more money than anybody, selling nickel rides on his train.

Throughout his school years in Whitefish Bay, a suburb of Milwaukee, Hank’s parents never pushed him toward any particular trade. “Above all,” says his mother now, “we wanted him to be a fine person.”

“I didn’t get into too many fights, to be honest,” Jeff says now. But he seldom provoked any. He was well-liked, and later on he was too husky. Besides, since early childhood he’d been taught it wasn’t gentlemanly to use force. However, in the second grade there was one boy who wouldn’t stop bullying him, so Hank “let the boy have it.” He came home tired, disheveled and winner by a nose.

However, his urge for self-expression, by more peaceful means, was always strong. “We had a pretty big back yard,” he recalls, “and I was always putting on a carnival or circus. I had a puppet show, too, and I used to do magic tricks.” He was most adept at making his Christmas money disappear buying magic equipment. Then one day he met a boy who turned out to be an expert magician and, as his mother laughingly recalls, “Hank gave the boy all of his gear, everything he had. And he’s never done a magic trick since.”

Like any boy, Hank went to the movies. He particularly liked Western stars and character actors. “I loved ‘Stagecoach,’ and I was a real fan of John Wayne’s,” he says. Of course, he never dreamed then that the day would come when he would be co-starring with Wayne. But then, there was never any stardust about acting for Hank McKinnies, no burning dream to be a movie star.

Hank’s first stage appearance was indirectly his mother’s idea, and sort of a family emergency. Mrs. McKinnies was on the board of directors of the North Shore Children’s Theatre group. All the member communities put on shows and gave exchange performances. “The talented ones would have the leads, then we’d bring in our children for spear-carrying or whatever needed to be done,” Mrs. McKinnies recalls. once, when the White-fish Bay group was stuck for somebody to play a sixty-year-old man, one of the members suggested, “Why don’t you get Hank up here and make him do this?” And Hank did.

Not long after this, their community decided to organize a radio group, The Children’s Theatre Of The Air, and they needed some adults to read certain parts. A friend asked Mrs. McKinnies if she would like to read. No, she said, she would not. Then she was startled to hear her son break in with, “I’d like to try.”

“This was the first I’d ever known of Hank being interested in radio—aside from listening to l Love A Mystery,” she says. “They were holding try-outs in the high school auditorium. Hank was too young to drive a car, so his dad took him over. They got there late and had to sit in the very back of the auditorium. There must have been two hundred people there, all reading for the same thing. By the time the director got to Hank, the boy had heard so many ahead of him, he knew the reading by heart.”

Hank loved radio and continued to work professionally in a wartime series, Those Who Serve. At first, as his mother recalls, “Hank was the soldier who called ‘Nurse! Nurse!’—but he got paid.”

Soon Hank entered the “Junior Achievement” program fostered by the Milwaukee city fathers to encourage youth activities in various fields. The motto: “Future—Unlimited.” This seemed to be the story of Hank McKinnies’ life then.

The record shows he was president of his class, president of the student body, football hero, recipient of the Citizenship Award and of a scholarship to Northwestern University. Nor was romance neglected. His “steady” was a lovely dark-eyed girl named Mary Mockly. As Jeff says, “I’ve always gone for brunettes.”

Whatever the activity then, the score was the same. He played halfback and end on Whitefish Bay’s Blue Devils team, and was co-captain the year they won the championship. In Hank’s sophomore year, he suffered a football injury which might have kept him off the screen, but didn’t. His nose was broken in seven places, and there was danger the cartilage would collapse forever.

“You’ll have to play with a faceguard if you ever play football again,” specialists told him. But Hank’s concern wasn’t the shape of his nose but rather the shape of the team and whether he was failing them. He used the faceguard—and typically, another injury (a broken arch), which could have knocked him out of the line-up, happened during the last game of his last season, when they’d already won the championship.

During the war, serving his hitch in the Navy, Hank McKinnies studied radar. He asked for sea duty and was assigned to the OGU—Out-going Unit—fully expecting to sail with the fleet to Japan. Instead, he was sent to the Ninth Naval District at Great Lakes.

In the fail of 1946, several months after his discharge, Hank entered Northwestern on a scholarship and the GI Bill. His college record reflected the familiar pattern of perfection. He pledged Phi Delta Theta, became president of the fraternity, and was graduated in three years.

If only Hank had failed somewhere— anywhere—he would have been better prepared for the setbacks he was to suffer later on. And he would not have blamed himself for “failing.”

Throughout college, Hank worked for his meals, “hashing at the Chi Omega sorority house,” as he puts it. “It was a little shocking at first to see the glamour girls coming down early in the morning without make-up, but I got to be real fond of them and felt real brotherly and protective toward them,” he says now, with an unprotective grin. He further augmented his funds by doing some modeling.

While at Northwestern, Hank couldn’t decide whether to be an actor or teach English literature “on a college level.” But the desire to act “sort of grew.” He played Peggy Dow’s father, an old New England sea captain, in “Years Ago.” During the summers, he worked with North-western’s stock company. “I played nine different character parts with nine different noses,” he laughs. “That’s the good thing about having a small nose—a small broken nose. You can always put another on top of it.”

Ape 8: Music was an early love of Jeff’s

When he graduated from Northwestern, Hank turned down a job teaching at a small university, deciding momentarily to get his Master’s Degree in radio at U. C. L. A. “Chicago was becoming a desert for radio then,” he recalls. “I had another year left on my GI Bill, and I wanted to come to California. I don’t know what I would have done about teaching, if nothing had happened in Hollywood.”

But many things happened—and soon. Hank’s life had never prepared him for some of them. The pattern of perfection was to be broken and, for the first time, he was to experience a feeling he’d striven so hard never to know—rejection. And he was to take even the smallest of failures to heart.

Hollywood discovered him when he met Estelle Harman, then in charge of the Actors’ Training Program at U.C.L.A. The famous drama coach was about to direct the university’s presentation of “All My Sons,” and suggested, “How about coming over and reading for the part of Chris?

“Hank wasn’t even a stage major,” Estelle Harman says now. “He was a radio major, and he was a little reluctant to audition. But finally he agreed to come. He read against some good people, but Hank was able to understand even at first reading that Chris wasn’t only an angry boy, but a tormented boy. He gave the part emotional dimension.”

At Northwestern, yen to act “sort of grew”

Hank trained long and hard for that part. “When I first met him,” says Estelle, “he was overweight and very casual about his clothes. He had the habit, like a little boy, of piling everything into his back pocket. I kept feeling that someday I’d probably find a whole fishing tackle back there, and I was always having him back up to me and emptying his pockets out in a big heap,” she smiles. “I would clip out pictures from Esquire and say, ‘Now this is how I want you to look.’ I talked to him about a diet—one of those green-salad-and-no-dressing type of things.

“Hank really stuck to the diet,” Estelle continues, “and the weight just melted off him. The suit he’d planned to wear in ‘All My Sons’ was flopping in the back by the time of the play, and it had to be tailored very quickly for opening night. He’d lost so much weight, the bone structure in his face showed through, and with his suit tailored to fit, this was a Hank with much commercial appeal. And with camera appeal.”

At 16: A high school hero and award winner

Although once that door opens, Estelle Harman emphasizes, good looks can be a disadvantage. “Being so handsome can be a handicap for an actor like Jeff. When Hollywood discovers he’s not only one of the handsomest, but one of the finer young actors,” she says warmly now, “there will be Academy Award material.”

Milton Lewis, Paramount talent scout, was convinced about Hank from the beginning, too. On opening night of “All My Sons,” after the first act, Lewis was backstage inviting Hank to read at the studio.

But for all the applause, the raves, and the fact that a major studio was talking about a screen test for him, Hank’s night of triumph was shadowed by a bad review in the school paper, written by a student who knew nothing about drama. As a college friend of Hank’s recalls, “A freshman journalism student covered the play. He didn’t like Hank’s interpretation and said so. And no matter how much everybody else praised his performance, Hank treated that freshman’s review like a consensus of all the top New York critics.”

But Hollywood’s consensus was soon to be heard, and that summer day in 1950, when Hank McKinnies walked through the gates of Paramount studios, was to change his whole life. He read in the “fish bowl”—so-called because of the one-way glass: “They can see you, but you can’t see them.” Afterward, Milt Lewis told him, “We want to option you to make a test.” And at the same moment, Hank’s eyes were “optioning” a very pretty dark-haired girl who’d walked into the office.

In Hollywood, the “perfection” pattern continued-he zoomed to stardom

“Barbara Rush, meet Hank McKinnies,” Lewis introduced them, explaining he’d also discovered Barbara at the Pasadena Playhouse, and that she was one of the studio’s star-hopefuls. Although he couldn’t know it, Lewis was then “casting” one of Hollywood’s nicest love stories.

Milton Lewis was enthusiastic about Jeff’s future. From the first he’d recognized in him “that indefinable quality—they call it star-magic, many things. Actually it’s indefinable. We used an intensely dramatic scene from ‘All My Sons’ for Jeff’s test, and I got Ed Begley, the original father from the New York cast, to play in the scene with him,” Lewis recalls. “Jeff gave a fine performance. He showed great depth and virility. In my opinion, he can do more dramatic things than he’s ever done on the screen. If they give him something really good to do, he’ll knock the heck out of it.”

However, there was nothing else he could do for Hank at Paramount then. It was a great test, and the studio was excited about it, but Henry Ginsberg, who was then in charge of studio operations, was in New York, and no decision could be made until he returned. Hank sweated out the days, then the weeks. Finally, one Saturday morning, he called his agent from a phone booth in the Theatre Arts building and found the studio head was back. The answer was “No.” Ginsberg had issued a studio directive: “No more newcomers are being signed.”

“You don’t shoot yourself,” Jeff says now. “I was disappointed, sure. But I still could have finished getting my M.A. and probably taught someplace.” Actually, he hadn’t seemed too worried about his future then. There was just a sense of failure, of not being wanted, not measuring up.

The following Saturday—“same phone booth”—Jeff called his agent and got a jubilant, “You’ve made it, Hank! You now have a contract, and you will be leaving for New York right away!” Darryl Zanuck had bought him after seeing Paramount’s test, and Hank was to leave on location for “Fourteen Hours.”

“It was just a bit part, but I had more in the picture than the Princess of Monaco,” Jeff says laughingly now. “Yes, Grace Kelly was in it, too.” His hometown paper, however, blazoned, “The Movies Discover Our Henry.” And the picture was billed as starring, “Whitefish Bay’s Own Jeffrey Hunter.”

In no time at all, Jeff zoomed to leading man—on and off the screen. On December 1, 1950, six months after they met, Jeff and Barbara Rush were married in St. Christopher’s Episcopal Church in Boulder City, Nevada. They had only two days for a honeymoon in Las Vegas because Barbie had to report back on location in Sedona, Arizona. Originally, they had planned to be married the following June, but Jeff had learned he would be out of the country on location for “The Frogmen” then.

This was to be the story of their married lives—two scripts passing in the night.

To Hollywood, theirs seemed like the perfect marriage. Two intelligent and equally talented wonderful people who would show the world how to be happily married and have two sparkling careers. Barbara Rush was as pretty as Jeff Hunter was handsome. Like him, she had led a comparatively charmed life—no struggles, no starvation. She’d had her share of scholarships, too. However, there was one difference. Barbara’s father had died when she was sixteen, and she’d had to make the decisions for their family. She also had the determined dream to succeed.

Before their marriage they’d discussed possible career conflicts. But, as Jeff says now, “Actually, all we could do was theorize about the future on any problems. That’s all any young people can do. You don’t know, you can’t know, what to expect. We’d signed to do pictures, and we felt we could go along and work it out.”

Perhaps, if Barbie had been different and less talented . . . if Jeff had been more dominating and less of a gentleman . . . if there had been fewer separations. . . .

At the time, Jeff had said, “Separations are bad. We know this. But we understand each other’s careers, we know their requirements. We hope to be able to work it out. If not, then we’ll make some other adjustment. But I want Barbie to have a career just as long as we can work it out.”

Jeff and Barbie were both winners in Photoplay’s “Choose Your Stars” contest that first year, and Jeff was as thrilled for Barbara as for himself. Theirs seemed a perfect union. They loved to study scripts together. They painted the dining room of their modest Hollywood apartment together. They played duets on the piano and were so grateful the landlady was in show business and didn’t mind the noise.

They talked of saving toward their first home. And much of the time they talked long distance via telephone. In fact, they were separated the first summer of their marriage. Barbara had an opportunity to work in summer stock with an important group in the East, and Jeff was kept busy before the cameras.

“This is the last time we’ll do this,” a lonely Jeff had said then. “Nine weeks is just too long. But I didn’t want Barbie to miss this. It’s such good experience for her.”

But this was far from the last time, for either of them.

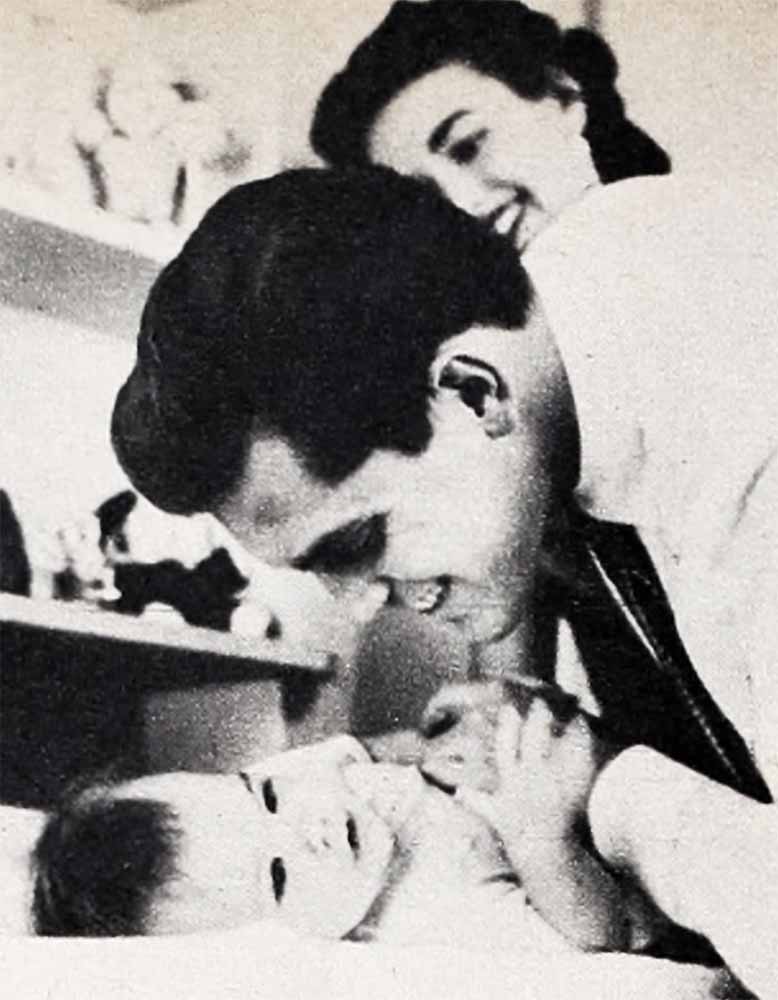

Jeff worried until the final hours whether he could be with Barbara when their son, Christopher, was born. He was scheduled to leave for England and Malta on location for 20th’s “Sailor of the King.” He was so happy when the studio postponed his departure for a week so he could be there when the baby came.

Jeff had tried to be rational about fatherhood, but at the final hour he acted the same as every father-to-be he’d ever seen on the screen. He rushed into the nursery with Barbara’s mother to see his first-born. “He’s a little darling!” Barbara cooed. Jeff, however, was a little shocked. “Is he?” he asked anxiously. As Barbara laughed later, “Hark thought the baby looked terrible—wrinkled and red and with one of his little ears lower-than the other. Hank was afraid he might be like Dumbo. He didn’t know, of course, that almost all babies look like that.”

And there was no time to await developments. “Well, I’ll see you in the movies,” Jeff said to Barbara a few days later, kissing her goodbye and heading for the airport. In London, a lonely Jeff kept looking for theatres where one of her pictures was showing, so he could watch her on the screen. Meanwhile, Barbie, a distinct amateur with a camera, flooded him with pictures, so he could watch his son grow. “You’re too far away,” Jeff would write back. “Please focus the baby!”

Jeff returned from Malta loaded with gifts for his son. Stuffed animals from Italy, a Swiss music box, little uniformed Bobbies from London.

During the months that followed, Jeff couldn’t be pried from his son’s side. Barbara was working much of the time, and Jeff was up each morn at seven, feeding Chris. He changed him, took sunbaths with him, played “duets” on the piano with him.

Jeff and Barbara finally bought their own home, a two-story gabled Byrd home in Studio City. They furnished it in Early American and settled down, after a fashion. But there were more separations, and the strain of their two careers was beginning to take its toll. Tensions which might have healed normally just didn’t have the time or opportunity.

As Jeff says quietly now, “Barbara and I just basically disagreed on practically everything. We rarely ever fought—we just disagreed.

“I think we would have had a much better chance without two careers,” Jeff says with conviction. “There are just too many divergent factors involved in two careers. And long separations never help anybody’s marriage. Love is basically a communication between two people, and it’s necessary for them to be together physically as well as in name.”

Barbara’s career began making demands on her. At Universal-International, enthusiastic executives were building her as an important young dramatic star. She was given a part in “Magnificent Obsession,” with Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson. Following that she was sent on location to Ireland for three months, co-starring with Rock Hudson in “Captain Lightfoot.” Jeff hoped to be loaned out for a picture in England, but this didn’t materialize. Instead, he went into Robert Jacks’ “The White Feather,” and went on location to Durango, Mexico.

When Barbara returned from Ireland, she flew to Mexico to see Jeff. On her return, she announced they were separating. There was shock and sadness among those who knew them. There was also the feeling among some other young stars that the same bell which tolled for Jeff and Barbara might also be tolling for them—and for their hope of combining marriage and a career.

And, despite their past difficulties, there was no doubt that the bell was tolling heavily for Jeff, and that he was deeply disturbed. This was a sense of failure which was really tough to accept.

It was certainly no part of life’s plan for Hank McKinnies. What had happened to him?

During the final days of shooting in Mexico, far enough from Hollywood to weigh and think and wonder, Jeff did a lot of thinking. His career seemed to be failing fast, too. He’d started out with such promise, and now he was virtually at a stand-still. Some plum parts had passed him by, including the lead in “Prince Valiant,” on which Jeff had set his heart—and which, according to studio rumor, had been virtually his.

“I was disappointed about that one,” Jeff acknowledges now. “It had been mentioned for me in the beginning, and I felt I could really do the part. Then it didn’t go through. They wanted a ‘young Prince Valiant.’ But then, of course,” he says philosophically, “this happens every day.”

Although few knew it, Jeff seriously considered leaving Hollywood then. He thought about Henry McKinnies and wondered what his life would have been like if he had taught English literature in college, instead of being a motion picture star.

“This happens when you go for some time without working,” Jeff says now. “After ‘White Feather,’ I had no immediate pictures scheduled. Barbara and I were getting a divorce. Nothing seemed to be coming up. I wasn’t thinking of leaving my studio—it’s important having a major studio behind you. It was just that I was restless, and nothing seemed to be happening.”

Then he was signed to make “A Kiss Before Dying.” This came as a gay tonic when Jeff could use a laugh. They shot the picture at the University of Arizona in Tucson, and the sorority and fraternity kids swarmed Jeff, inviting him to their dances and various college functions. In the evening Jeff would play the piano, surrounded by crowds of collegians singing up a storm.

In searching for the answers, Jeff was to find the key to tomorrow and a sense of fulfillment he’d never had in the Deep South—in Clayton, Georgia, where he went on location for Walt Disney’s “The Great Locomotive Chase.”

The mood of the people, the tendency to take time to live—and to live more fully, more richly—had a calming, steadying influence on Jeff.

The townspeople of Clayton worked on the picture, and on the set one day Jeff met an inspiring man, who was working as an extra. A “devoted humanitarian,” a brilliant man, and a student of life—culturally and spiritually. Jeff visited the man’s home, and they had long talks between scenes, there in the Georgia countryside. all of which proved invigorating and uplifting for Jeff, just when he needed it most.

“They take time to live there,” Jeff says quietly. “Time to live and pursue many things.”

Today, Jeff’s all-around living is reflected on the mailbox of his smart, modern Brentwood apartment, which reads, “Jeff Hunter, Hunter Enterprises, Henry McKinnies.” And he’s pursuing many things.

With his friend and business partner, Bill Hayes, Jeff’s producing documentaries such as “The Living Swamp,” which won an award. He and Bill are also expanding into feature-length productions in Central America, and Jeff has an eye on Siam. They’ve organized “Executive Business Management,” with star-clients like Rita Moreno, Ben Cooper, and Jeffrey Hunter.

But, as Jeff says, “I don’t want to become too cornered with interests that will interfere with my personal life and not give me time for self-expression. Time to act, and read, and enjoy music.”

As for his motion-picture career, Jeff’s so successful he’s competing with himself on screens throughout the land. He’s been getting bravos from critics everywhere for the best role of his career, as a quarter-breed Indian in “The Searchers,” in which he co-stars with John Wayne. He got the part because director John Ford saw his performance in a picture called “The Three Young Texans,” not one of his proudest credits by far. “That was the only thing Pappy had ever seen me in on the screen,” says Jeff.

So who is to say what constitutes a picture worth making, says Jeff, philosophically. “I’ve been very lucky actually, and my salary has gone up with every option.

“And the field is opening up now. I have a new contract which allows me to make one picture a year at the studio with our own company.” Jeff was on loan-out to U-I, to co-star with Fred MacMurray in “Gun for a Coward,” and he recently did a fine off-beat Western characterization in 20th’s “The Proud Ones.”

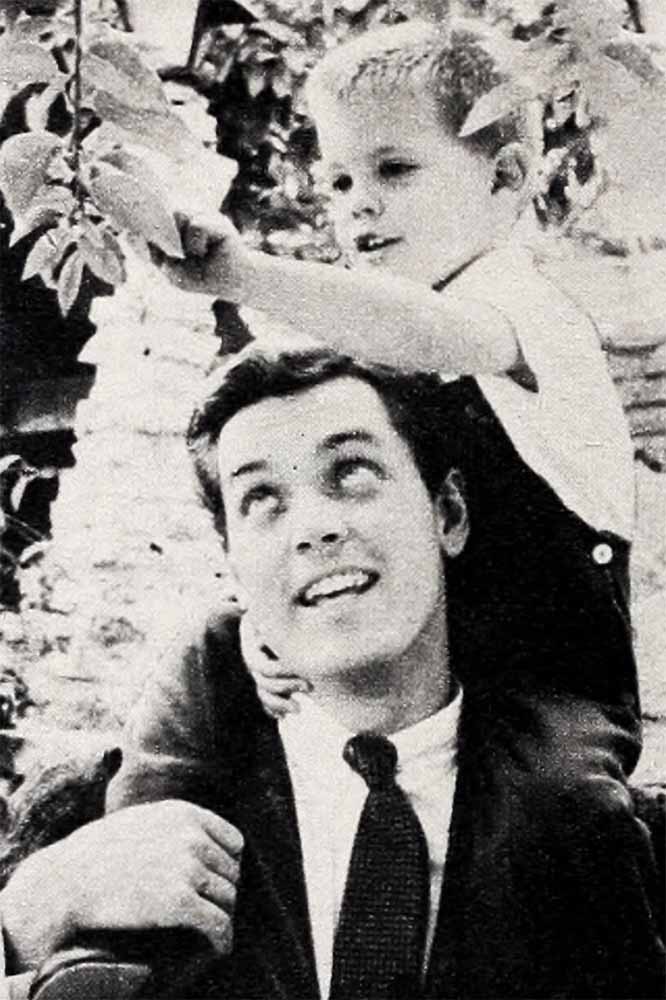

But above all, Jeff’s pattern for living fully now means spending as much time as he can with Christopher, his sturdy little four-year-old.

No star-bachelor lives in Jeff’s smart Brentwood apartment with the lush tropical foliage. A devoted father lives there. And there, too, in plain view, is a boy-sized shiny red tractor with a trailer wagon. It gets a busy work-out, too, when Chris is around.

Jeff has equal custody of Chris. “There’s no time schedule for being with him—that’s the way Barbara and I wanted it. It’s very flexible. I can go see him any time, and I have him with me on Sundays. I take him to little-boy land—whatever he wants to do. We go to the beach, or to the kiddie carnivals, or go fly kites, or to ‘Busyland’—Chris’s pronunciation for Disneyland.”

Jeff never keeps Chris overnight, believing it better for his sense of security and happiness to sleep in his own bed.

Chris is not yet really aware of his divided life. He hasn’t yet asked the usually dreaded, “Why don’t you live at home, Daddy?” As Jeff says, “He’s never asked me anything about not sleeping at home. And I try to get over there as much as I can, spend as much time with him as I can.

“Chris is a well-adjusted child. He’s very happy and very healthy. And he expresses himself very well for a four-year-old.”

Thus far, it has been a little hard for the former scholar of Whitefish Bay High to keep up with Chris. One night recently, Jeff phoned Chris to chat with him. “What did you do last night?” he asked him. “I was home watching Venus,” Chris told him. “Venus jumped over the moon.”

“Venus jumped over the moon!” his father says laughingly now. “Holy smoke!”

Jeff is determined that Chris will have every educational opportunity, “so he will start out in life with an appreciation for art and music and all these things for his own enjoyment.”

And Jeff plans to remarry. “Oh, yes, I’H get married again, definitely. I want a home and all that marriage means. I want to travel, and I want my wife to come with me.” And when he does marry again, “I don’t want to combine careers and marriage. As a general rule, one career is wiser in marriage, I believe. Of course, there are always exceptions, but—”

But Jeff can accept philosophically now the fact that his marriage wasn’t that exception. But beyond this, beyond today, he is leaving the future to the prophets.

“I’m past the stage where you try to project yourself too far into the future. I’m trying to live life a day at a time now. To live every day fully and enjoy it.” Living every day this way, Jeff knows at last, adds up to that future unlimited.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1956

AUDIO BOOK