Glenn And Annie’ Love Story

Annie Castor Glenn put her head down on her knees and wept. She couldn’t help it. It was not just because she was tired—although she had been up since 5:30 that morning. And she had been busy ever since, setting out trays of plates and cups and glasses, piling dishes with coffee cake and buns, getting breakfast, greeting the people who were to spend this day with her. But she was not tired, not really—excitement gave her extra energy. Nor was she simply frightened, although she had reason to be. Her husband had just begun to circle the earth.

. . . Ahead of him loomed the dangerous re-entry into the atmosphere. . . . Any of a hundred possible disorders could end in his fiery death. At the moment of the launching, when smoke and flame belched from the rocket, their daughter Lyn had hidden her eyes and cried. . . . But Annie herself had been calm. She had reached out to pat the fourteen-year-old without taking her eyes from the television screen. Nor did she cry purely from relief at the dangers that her husband had already survived, nor from tension and taut nerves. For all these things—fear and relief, weariness and tension—all these had lived with her for so many years that they had lost the power to make her weep. . . . Nonetheless, she did cry. And the millions who, a few days later, would hear the Mayor of New York call her a “wonderful courageous lady,” could only agree, tears or no tears.

Now she lifted her head and dried her eyes. She turned a little to smile at the anxious circle around her—her daughter, her son, her parents, her closest friends and neighbors, the Millers. But before she saw any of them clearly, through the mist of tears she saw one other thing. It was her husband’s pearl-encrusted sword, hanging above the mantel.

How beautiful it was! As beautiful as on the day she had seen it first, so many years ago. That day she had touched it reverently, because it symbolized the fulfillment of John’s first dream—to become an officer of the Marines.

How many years had passed since that day of shining pride! How many things had changed!

The changes had begun with the sword, for it had divided past from present, one life from another, one way of love from another way.

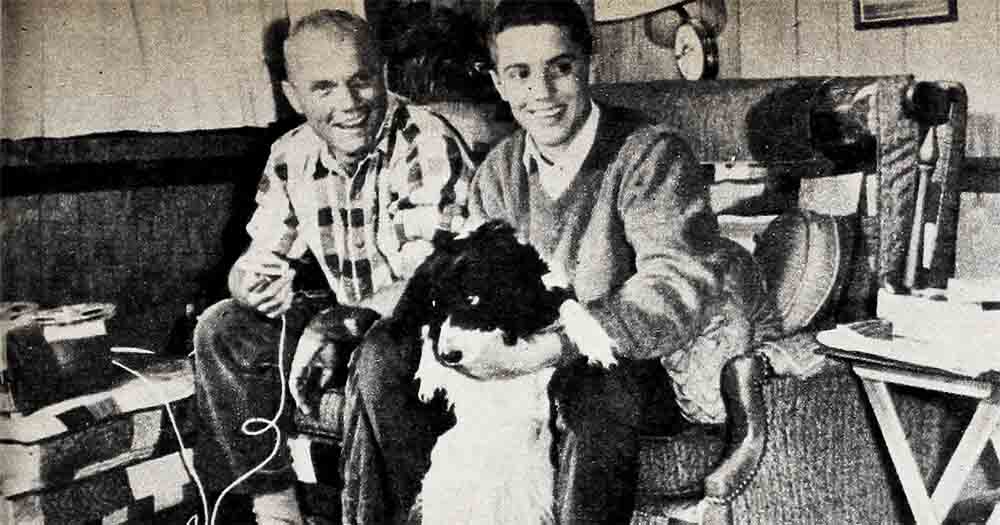

Once—long before the sword and all that it meant came into their lives—Annie Castor and John Glenn, Jr. were inseparable. They had known each other so long that Annie could not remember meeting John for the first time—they had always been together. When she searched her memory, she decided that they were probably six and seven—she the older—when they became “pals.” They played together until one day they looked up with new eyes and each saw the other. Not as the dear friend, but as the one—the only—dearly beloved, now and forever. After that they were no longer playmates but “steadies.” They went on to high school, they danced instead of playing games. But still together. Annie and John, always together.

Puppy love, the older and wiser called it. Maybe it would last, they said; maybe it wouldn’t. Last or not, it burned then with a warmth that gave luster to their successes, comfort to their failures. When John played the lead in the senior play and sang in the choir at church, it was Annie he looked to for the approval that really mattered. Her shining eyes counted more than all the applause and praise. When he made only the second team at football, it was she who consoled him for the impatient hours of bench-warming while other boys ran and tackled and scored (poor John, who was known even then for wanting things so much!) and made him see that it really didn’t matter. (So that years later, when Life Magazine wrote him up as a big high school football star, John Glenn was able to laugh about it.)

But she was not only on the sidelines of his life—there were many things they shared equally. Their love of God, for example. At the Presbyterian Church, Annie played hymns on the organ and John sang. She took church doctrines very seriously and John agreed, even once berating his friend Ed Houk for singing “Hail, hail, the gang’s all here, what the hell do we care,” after both boys had taken a vow against using profanity. Little things, all, but part of the fabric of their young lives. They were bound so close that even the food they ate and the prayers they said were still another thread of the bond between them. Annie and John—never apart.

John went on to Muskingham College, right in New Concord where they lived. And though all the girls looked at John, he looked only at Annie. But then came the war. America’s fleet was crippled at Pearl Harbor, and her island strongholds in the Pacific were conquered one by one. John Glenn read the papers and now he began to look past Annie—he began to look at the stars.

“I want to be a pilot,” he said. “I must fight in the war.” And of course that was to be expected of John, who loved his country, loved his God and was never one for half-way measures. Annie was proud of him when he took civilian flying lessons, then quit college for the Marines.

Their first separation

And thus the sword lured him away from her.

Away. John and Annie—together no longer. Of course, millions of girls and millions of fellows were separated by the war. Of course it was a good thing to test love by the trial of separation, in which puppy love would surely fail and true love endure. And of course there were letters and phone calls and weekend leaves.

(But would Annie Castor have been human if just once she had not asked herself, Did he have to go before he was called? If he loved me as much as I love him, wouldn’t he have waited? Has any woman said goodbye to her man without asking that, in her heart, if only once?)

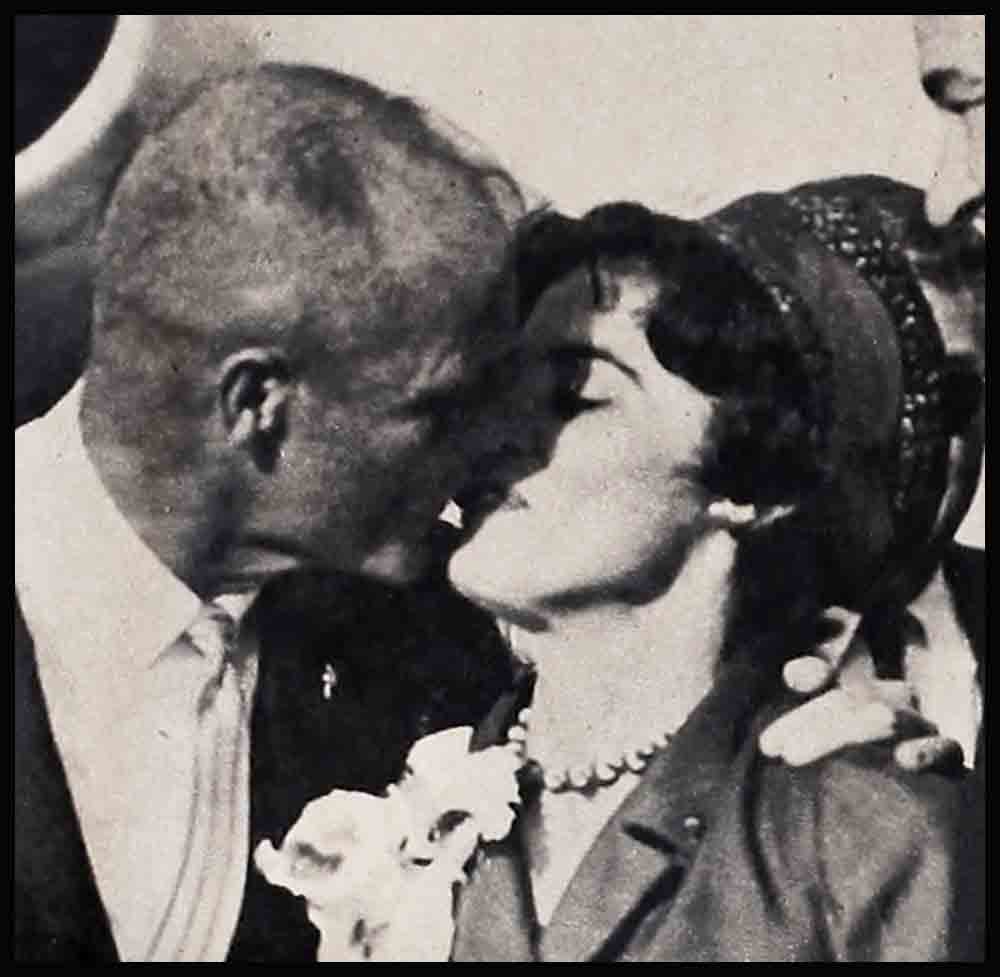

In the spring John came home wearing gold wings and a trim blue uniform, and, love having endured, he and Annie were married on a sunny April day. “Till death do us part,” the marriage service read, and surely it seemed to them that that was how it would be, John and Annie together again. God had joined them together. No man would put them asunder.

But the war sundered them, quickly enough. They had a honeymoon in California while John trained. They had a baby, too, a son they called David. He was old enough to wave bye-bye but not to know what it meant when John went to the Pacific to fly against the Japanese enemy.

Annie knew, though. “It broke my heart.” So terrible was the moment of loss that neither she nor John could face it openly. So: “I’m going down to the corner store and buy some chewing gum,” said John Glenn, on his way to war. “Well. don’t take too long,” said Annie, his wife, not knowing if she would ever see him again.

Love. What does love become, stretched across thousands of miles, squeezed into little words on V-mail stationery, in danger of sudden death by flame and bullet, of slow death by time and distance? How does love survive in a woman whose heart is broken, and a man whose skill and thought is given over to staying alive while dealing in death? John and Annie, together no longer—what becomes of them?

John won five Distinguished Service Flying Crosses and an Air Medal with eighteen clusters. He was a hero, one of the most decorated Marine pilots of World War II. Annie Glenn received the news and congratulations with quiet, smiling pride.

(But was there ever a woman who sent a man off to war without thinking, I don’t want a hero—I only want him to come home alive. Let the men who have no families, the men less loved, take the risks. Let my man remember me and take care of himself.)

Home again . . . alive

Somebody bigger took care of John Glenn. He came home from the war alive and well. Did he find things a little changed? Was David bigger than the snapshots had shown? Were Annie’s dark eyes a shade more solemn, matured by waiting, by loneliness, by fear? Had John himself changed, back there in the daily company of death?

Two new people picked up the threads of an old love. Surely those threads had changed, surely a little of the shine had rubbed off under pressure, surely they formed a new pattern now, of man and woman, father and mother, instead of boy and girl. But equally sure, the pressures had made the strands stronger, and the pattern, though more complex, was more beautiful.

Love had changed, but love endured.

Out of love, a new life was born. They named the little girl Carolyn and called her Lyn. Now life was good and love was easy once again. Annie raised her children and worked for charity. John did his job as an officer and taught in Sunday School. Annie and John—together once more.

But the Korean War came next. Lyn was a big girl of five when she, like her brother before her, saw her father off to war.

(Did Annie Glenn, leading her children home from the airport on that chilly day in 1953, say to herself. He fought in the last one, the war that was to be the end of wars. There are those who did not fight then. Why must he go a second time? If she thought it, she rejected it at once. But what wife wouldn’t have thought it?)

John became a hero again. It was his nature to be quietly, efficiently, almost casually a hero. His crew referred to their plane (officially the Lyn-Annie-Dave) as a Hying doily, so full of holes was it. But to Annie Glenn, waiting at home once more, posing her children for smiling pictures to send to Korea, all that mattered was that the doily kept flying.

Eventually John came home again, safe and sound. Surely her prayers were prayers of Thanksgiving now. Thank you, God, for past dangers safely survived. thank you for this present moment of homecoming, but thank you most of all for the quiet future ahead, for the fearless nights and happy days I will know, when death is not in every ring of the doorbell and the phone.

He courted new danger

But that was not to be the future for Annie Castor Glenn and her husband and her family. Because John had decided to become a test pilot. He was going to take into the air the new, untried machines and see if they were safe for other men to fly.

Why? Because John Glenn. with his dozens of combat missions, his medals, his luck and his faith and his extraordinary ability to handle an airplane, knew himself qualified for the job of protecting other pilots’ lives by risking his own. Because someone had to do it. And John Glenn was a man who could not leave a duty undone.

But to Annie Glenn, did it not mean that never, never, never would she see her husband off to his work without wondering if she were seeing him for the last time of all? Never, never say goodbye without wondering if she were saying it forever? (How many women would have cried out. No, I have borne enough for love of you—now give up this one duty for the sake of your duty, your love, to me. How many would have added to their prayers one more; Lord, make him change his mind; Lord, make him stay on the ground!)

John Glenn tested the Navy’s planes, broke the coast-to-coast speed record, did many a dangerous feat and lived to do another. And Annie cooked his supper as if she knew for sure that he would come home for it. She prayed—but she also learned to take an interest in the technical aspects of her husband’s job. and never to take note of the fear any more. Their children grew up bright and strong and friendly. And love—love bent beneath the burden of danger it was never to escape and emerged smiling and strong. Love showed in John Glenn’s voice when he came home saying, “Hi. Squirt” to his wife, in memory of the easy days of love and youth. Love lived in Annie’s eyes, still calm; in her faith. unshaken; in her fingers, playing hymns of thanksgiving on the electric organ for John and the children to sing. And if ever fear crowded in despite all defense, she could remind herself that what she did, thousands of other service wives did. That John’s risks and duties were not, after all, unique.

But when her husband came home to tell her that there was a new project afoot—to put a man into space—and he wished to be a candidate for that role; that he had been told he was too old but thought he had a scheme to get into the project anyway—then did Annie Glenn’s heart sink in spite of herself? For this was uncharted country, unknown risk, toward which John now yearned. Did she harbor a tiny hope that this time he would fail to achieve his dream?

The ultimate risk!

He succeeded, of course. He wangled the assignment of “observer” of another man’s tests, and when the man failed. John Glenn stepped forward and offered to try. He passed the tests, of course. He became a space candidate, one of the ultimate elite, one of the tiny group of Astronauts.

Now surely not even faith could prevent Annie from knowing that John’s days might well be numbered. Even John Glenn’s luck could not last forever; not even John Glenn’s skill assure a return from the unknown shores of space. Now every moment, every second of John-and-Annie-together was doubly precious. For each might be one of the last.

But given his choice. John Glenn chose to live not at home with his family in the new house in Arlington, but on the base where the Astronauts trained. Where he could study, work, practice his role every waking minute.

And so, for three long years, love had only phone calls and weekends and hurried visits in which to store the precious memories it might have to live on forever. Now Annie Glenn once more raised her children without their father, followed scientific news as she had once followed battle reports. Day followed day, each one hurrying toward the moment when time might stop forever for Annie Glenn.

Now she was told that John was not to be the first man into space. but merely a possible last-minute substitute. (How disappointed he was, how stricken the town of New Concord!) But until the moment when Alan Shepard shot through the earth’s atmosphere, leaving John behind, Annie waited and prayed and kept herself calm enough to walk a golf course with a club in her hand.

And now she was told that her husband would be the first man put into orbit. Now she said goodbye to him in person, and goodbye again on the telephone as he lav strapped in his capsule (“I’m going down to the corner store . . .” “Well. don’t take too long . . .”) and fixed chili for the crowd in her living room, and stared at the three television sets on which the moment of his death might appear—and then heard that the shot was called off, to be scheduled again tomorrow, or the next day or week or month. She would have to begin all over again.

“. . . and women must weep”

At last the day came. There were no more postponements. This time it was real. This time Annie Glenn rose at dawn, kissed her children, welcomed her neighbors, ate her breakfast, looked out at the reporters trampling the ivy on her lawn, turned to the television sets, saw the capsule shot into air, wept—and then ceased to weep. And all the while, time, with its changing burden of Annie-and-John-together, Annie-and-John-apart, hung in the balance.

In Life Magazine, Loudon Wainwright wrote of the moment when John Glenn lifted from the earth toward the stars: “Three years of hope, of disappointment, of anger, of loneliness, of joy, of all the feelings that Glenn and his wife and children had shared during that period, were plunging toward their dangerous terminal instant in time.” He was right—but only partly right. For it was not three years, but a lifetime which came to its climax in that moment.

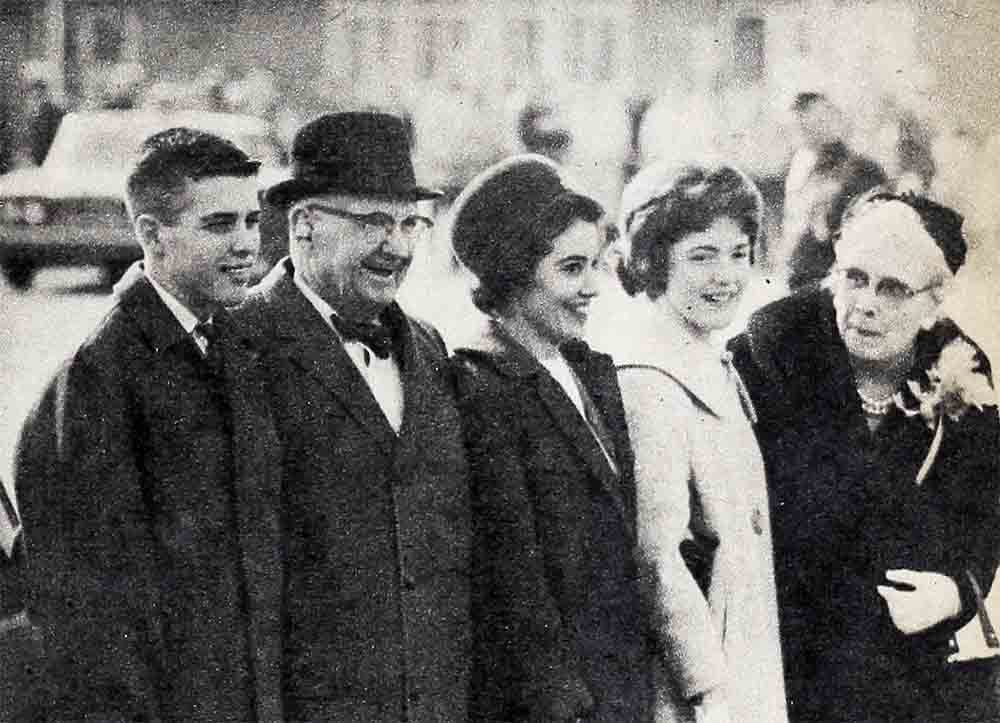

We know, of course, how the story ended, for its end was written in headlines, shown in pictures, seen in the faces of a world gone joyously mad. We know of the parades and the honors, the babies named after Annie Glenn, the streets named after her husband; we have read the words of praise heaped upon them.

But is there a woman alive who thinks such a moment of glory is payment enough for the moments of terror past and to come? Who considers a day in the sun as compensation for a thousand nights in the dark of fear and loneliness? Who would dream that a goodbye, like all John Glenn’s goodbyes, could be wiped away by words of praise for her fortitude, spoken by strangers?

Where Annie gets her courage

No, the rewards and medals. the praise and the parades—these are not the things that make Annie Glenn’s life the thing of faith and beauty that it is. These are not the hopes that balance the fears, these are not what enable her to face the future as she has the past. This is not why Annie is able to keep her head high when love changes; when time stops; when, again and again, Annie-and-John-together become Annie-and-John-apart.

No—what makes the whole thing bearable—and even worth while—is one truth. One rare and precious truth that one man put into bittersweet words three hundred years ago, as prophetically as if Richard Lovelace were writing them today for John and Annie Glenn:

Tell me not, sweet, I am unkind

That from the nunnery

Of thy chaste breast and quiet mind,

To war and arms I fly.

True, a new mistress now I chase,

The first foe in the field;

And with a stronger faith embrace

A sword, a horse, a shield.

Yet this inconstancy is such

As thou too shalt adore;

I could not love thee, dear, so much,

Loved I not honor more.

—CHARLOTTE DINTER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1962