Their Marriage Is A Lifetime Honeymoon

The soldier and his girl walked hand in hand toward the small white church. Their steps quickened as a group of clouds gave way to a sudden shower. And they broke into a run when the shower became a mighty downpour. Once inside the church, the soldier turned to the girl with concern in his eyes. Poor kid, he thought. He knew how much a wedding outfit could mean to a bride. And now the lavender suit was splashed with rain—the flowered hat soggy.

The bride-to-be took off the hat to inspect the damage. The groom-to-be held his breath, waiting for a sign of tears or temper. Her grin was slightly waterlogged, but she managed to find words. “If only they’d been real flowers,” she sighed. “It might have done them some good.”

That was the end of Miss Lydia Clarke’s hat. It was the beginning of—well, it was quite a beginning. There they were—a fellow who’d vowed he’d remain a bachelor for the rest of his days, and a girl who’d insisted that she’d be no man’s Hausfrau.

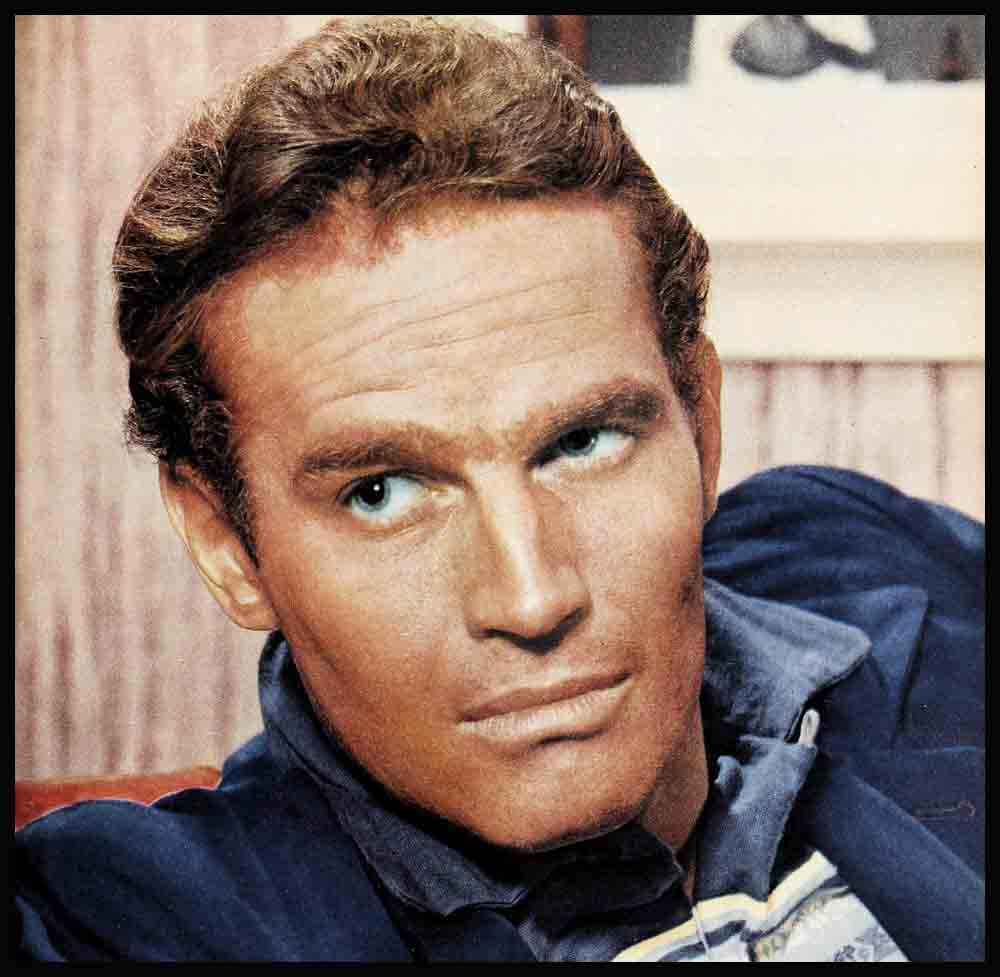

Charlton Heston had entered Northwestern University with the firm conviction that he would never wed. He wanted to become an actor and he was certain that it would be impossible for an actor to find anyone who could make him a good wife. He had still another theory: “I often think people get married for insufficient: reason—just because they believe they ought to be married. I don’t think you should get married if you can be happy unmarried.”

Then Lydia Clarke walked into his classroom and into his life. “And what are you going to do when you find that you can’t be happy single?” Chuck was soon asking himself.

He found the answer. He proposed. However, the lady also had plans which excluded matrimony. “Marry me,” he’d say.

“Go away. I’m not interested,” she’d retort.

Only a war could have budged him. And since there was a war, eventually he went away. He was in the Army, taking his basic training in Greensboro, North Carolina, when he received a wire from Lydia. “I have decided to accept your proposal,” she stated briefly.

So maybe it was fitting that the weather, too, did a turnabout on the day that these two former rebels against marriage picked for their wedding. Since that March 17 in 1944, Lydia and Chuck have not only proved there can be exceptions to the saying, “Happy is the bride the sun shines on.” They’ve also merrily upset the rule that a wife’s place must be at her husband’s side—and vice versa. For about a year now, Lydia has been with the Chicago company of the stage hit, “The Seven Year Itch,” while Chuck’s movie and television work has kept him shuttling back and forth between Hollywood and New York. For ten years, they’ve kept their love alive through poverty, separation, and perhaps the greatest of all marital hazards—Hollywood success. The question which has been asked by both fans and friends is how?

“The most important thing is to be sure you marry the right person in the first place,” says Chuck. And this is one reason why neither Heston will ever step into a divorce court with that familiar complaint, “We have nothing in common.” It was their mutual interest in the theatre that first brought them together. However, in those days, Chuck was concentrating solely on his own career—Lydia on hers. It was their mutual love that made Lydia’s success important to Chuck and Chuck’s success important to Lydia. “It’s possible to respect someone you don’t love,” Chuck has said. “But it’s hard to love someone you don’t respect. I have the greatest respect for Lydia’s work and for the things that are important to her.” It works two ways.

The ability to compromise plays a large role in any marriage. What the Hestons have is even stronger—“the desire to compromise,” they call it. As far as she’s concerned, Miss Lydia Clarke’s career is secondary. She’s steadfastly refused to sign a Hollywood contract because it would mean that she couldn’t leave the West Coast when Chuck leaves. On the other hand, Chuck has never put his foot down about her work. Last spring, when they returned from a location trip, Lydia headed east for television. Chuck went west for a movie. One evening his phone rang. It was Mrs. Heston. “They’ve offered me a lead in ‘Seven Year Itch,’ ” she told him, “the Chicago company. What shall I do?”

“Take the part,” he insisted. “But don’t do any more television before you start rehearsals. Come back here while I finish the picture.”

Often it’s been necessary to work at it long distance. It’s been that way since the beginning when, two months after their wedding day, they faced their first separation. Chuck was sent to the Aleutians. Lydia returned to Northwestern University. They both wrote daily. And now when they’re apart, they do the same. Recently, however, Chuck forgot to include a bit of vital information in one of his communiques. He mentioned that he would be catching a plane, but he neglected to say which one. He knew that Lydia had a morning rehearsal and an afternoon matinee and he didn’t want to add a 4:00 a.m. visit to the airport to her schedule.

Lydia knew that when her husband flies, he likes to sleep en route. She checked evening flights from Los Angeles and, on the chance that he would be on the first morning arrival, she drove to the airport. The first voice Chuck heard in Chicago was a sleepy, “Good morning, darling.”

Chuck married no Hausfrau, but he married a girl who has a remarkable talent for making a home wherever she happens to be—Chicago, Michigan, New York or Hollywood. And she can turn out a meal to rival one dished up by a Waldorf chef—a talent she has acquired through the years. As a brand-new bride, she knew little about cooking. During their early days in New York’s Hells’ Kitchen, she shopped on fifteen dollars a week.

Although times have changed considerably, she still runs into food problems now and then. Once, for instance, she finished a television show in New York and flew to Hollywood where Chuck was at work on “The President’s Lady.”

“Lydia was tired, dead tired,” Chuck remembers.

Lydia also remembers. She dropped her luggage at their apartment and rushed out in search of ingredients for a fine dinner. She even baked a cake, and soup was on when Chuck walked in. He took one look and seemed to turn pale. She watched as he choked down each bite of his fine dinner. Finally, he gave up. “I’m sorry,” he groaned. “I just can’t take any more.”

Lydia tried another piece of meat. In no way did it resemble shoe leather. “I didn’t want to mention it because you’ve gone to so much trouble,” her husband explained. “But we shot a breakfast scene today . . . practically all day. And I’ve been eating since shortly after dawn.”

Lydia breathed a sigh of relief. “It’s hard to be married to an actor,” Chuck admits. “And an actor’s wife, especially if she’s an actress herself, has a double job. In addition to her own career, she has to be able to cook for her husband and be able to give him a kind word when he comes home after a tough day. She has to be mentally equipped to discuss his work intelligently. She must soothe his melancholy moments of deep disgust with all the work he’s ever done or ever hopes to do. She has to be prepared and inclined to remind him of the kind of work he wants to do and the goal he’s headed for.

“She has to be able to live out of a suitcase when you’re working . . . sometimes cook out of a footlocker when you aren’t. She has to be able to make a home in a cold-water flat, or, with a choice of three apartments and a ranch, make the one home wherever she is.”

Neither Chuck nor Lydia will ever forget their years in the cold-water flat. Their wealth was limited to love and laughter because they had no money. The problem of earning a living kept them both working whenever work could be found.

Chuck still tells of a Christmas which showed promise of being especially dreary. Lydia produced a package, as if by magic, on Christmas morning. “We needed a present,” she explained, handing him a couple of books on painting which she’d known he’d wanted.

However, the lavender suit was missing from her closet. She’d taken it out, packed t in a battered suitcase and spent an entire afternoon walking up and down Ninth Avenue, visiting secondhand clothing stores. “Throw in the suitcase and I’ll give you twenty dollars,” one man said.

“Sold,” said Lydia, taking the bill and departing for the bookshop.

As far as Lydia’s wardrobe is concerned, her hats have taken the worst sort of beating since her wedding day. Something semi-tragic seems to happen to each new one. First it was rain. The last time, it was wind. Chuck was driving her to a radio show in Chicago. The convertible top was down and there was a brisk breeze. As they were passing the water tower on Michigan Avenue Lydia reached for her hat—and missed. “It’s gone,” she shouted.

“What’s gone?” inquired her husband.

“That hat. It went that way.”

Chuck stopped the car, got out and momentarily disappeared. He returned victorious. “At the risk of life and limb,” he said grandly, handing her the headpiece. “Only for you would I chase hats down Michigan Avenue.”

The hat looked as if he might have found it beneath someone’s foot. Which may or may not prove that it’s hard to be married to an actor.

“It isn’t exactly easy to be married to an actress,” Lydia claims, thinking of the endless separations.

Ten years of memories, ten anniversaries—and they never know where they’ll spend the next one. The first found Chuck in the Aleutians, Lydia at Northwestern. The ranch in Michigan was the scene of the second. They were in the middle of Little Theatre rehearsals in North Carolina when the third rolled around. The next year they celebrated in New York, where Chuck had a role in “Antony and Cleopatra.” Number five was spent in Georgia, while Chuck was shooting an Army training film. Lydia was touring in “Detective Story” when her husband joined her in Minneapolis to celebrate a happy sixth. The following year, they were in Gallup, New Mexico, en route back to Hollywood from a location in Florida. After that came London. Number nine found them in Nashville, Tennessee, for the world premiere of “The President’s Lady.” Chicago seemed the most logical meeting place for their tenth anniversary celebration. And Numbers Eleven to Fifty?

They don’t know and they won’t care—so long as they’re together.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1954