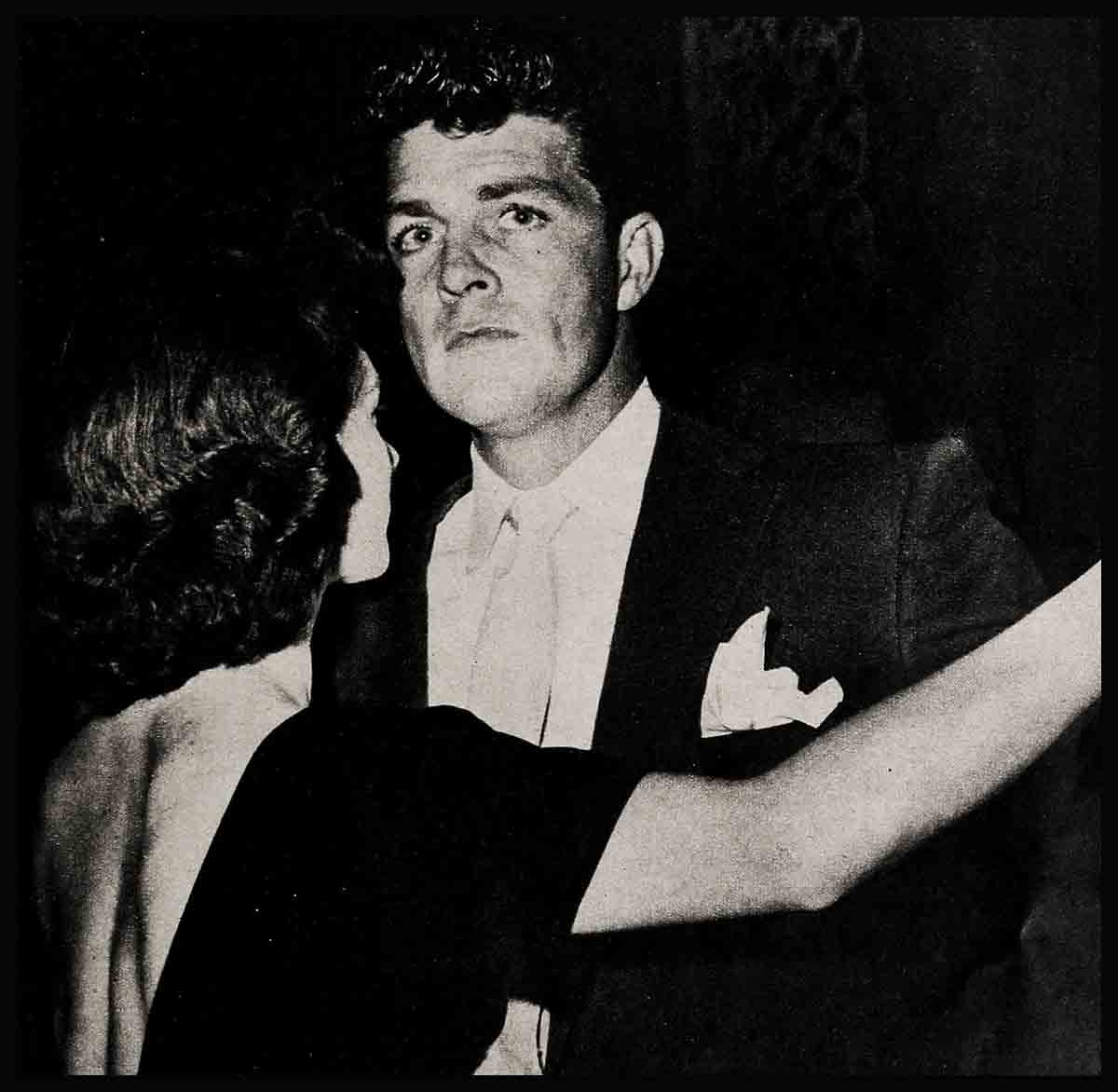

Going . . . Going . . . Gone!—Frederica Jacqueline Wilson & Dale Robertson

“I guess he never loved me,” Jackie Robertson mumbled, choking with tears. “Or maybe there’s just no love in his heart.” This beautiful twenty-two-year-old girl was talking about her impending divorce from actor Dale Robertson. She was trying to reconstruct the tangled web of their unhappy marriage.

Why had this marriage foundered?

Was it Hollywood’s fault?

Was the marriage too sudden?

Was Dale to blame exclusively?

Was Jackie an inadequate wife?

What went wrong with a marriage that three years ago was blessed with so much promise?

You recall its romantic foundation. MODERN SCREEN covered the love affair in detail. So did many newspapers.

In 1951, on the set of Friendly Island, Mitzi Gaynor introduced Jacqueline Wilson, a poised, sloe-eyed young actress, to Dale Robertson.

Dale was then as hot as a freshly-fired pistol. He had finished Take Care Of My Little Girl with Jeanne Crain. Betty Grable wanted him for The Farmer Takes A Wife. He was receiving three times as much fan mail as Marilyn Monroe.

The tall Oklahoman took one look at Jackie and the total effect was nothing. A few weeks later producer Andre Hakim gave a dinner party, a small affair by the standards of the continental Hakim. There were thirty or forty guests. Among them were Jacqueline Wilson, sophisticated, well-bred, and nineteen, and Dayle LyMoine Robertson, handsome, drawling and between thirty and thirty-five years old.

They began to talk about horses. Jackie had been born in Paris, reared in Princeton, educated in eastern finishing schools. She had been a member of the Eldridge-Hartford: Hunt in Baltimore.

Robertson was a frustrated cowboy who had attended Oklahoma Military College and worked later as a shipping clerk for the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company and as a jackhammer operator for the Charles M. Dunning Company, a construction outfit in his native Oklahoma City.

All the polish he had, he wore on his fingernails. But his is a magnetic personality. He has the same kind of air, good looks and command of situations that characterized Gable when he came to Hollywood twenty-five years ago. And Jackie Wilson, understandably, was attracted to this rugged, square-shouldered six-footer.

“We met on a Saturday,” she remembers. “Then he called on Sunday, proposed on Monday, and we were married three weeks later. If things had worked out, the hurry, the haste, the mad rush would’ve been swell. But the marriage didn’t take; so now I can say the courtship was too fast.

“It’s easy to be wise after it’s all over. But I was so much in love with Dale—I’m still very much in love with him—that I guess love dulled what little common sense I have.”

Dale and Jackie were married on May 9, 1951. Dale’s studio associates seemed to be genuinely pleased.

“Marriage is just what this boy needs,” one actor said. “He’ll hit the top in no time. Dale is pretty unusual for a Hollywood actor. Not a phony bone in his body.

“Know where he lives? Out in Reseda on a G.I. tract. Pays $52 a month for rent. And no marriage will make him move into any of those swanky joints in Beverly Hills.

“I hope Jackie realizes that she’s got a real man in Dale.” That Dale was a real he-man, Jackie soon recognized. He was crazy about fights, baseball, softball, dogs and, of course, horses.

When he wasn’t indulging his passion for these activities, he was hunting or driving to and from Oklahoma City. He worked at the studio, of course, and they worked him long and hard because the young movie-goers liked him.

Dale seemed to pride himself in retaining a fierce independence. Around the studio he referred to his wife as a “fine filly” and, in the words of one perceptive actress, “He gave the impression that nothing, neither marriage nor contracts, would stop him from doing whatever he felt like doing. Marriage changes a man’s outlook. It gives him new duties, new responsibilities. Not Dale. He seemed to strut around as if to say, ‘See, nobody can rein me in. I’m a free soul.’ ”

Out in Reseda, living in the stucco bungalow, Jackie was confused and unhappy. Away from her friends and family, young and inexperienced, her career abandoned, she was eager and experimental. But she was alone most of the time. Even when Dale was at home, he was so continually involved with horses and picture-making and sports and business deals that there was little time for family life.

“Occasionally,” Jackie says, “he told me that he loved me. And maybe he did. I just doubt it. Because if he really loved me then he would have tried to work at our marriage.

“I told him that marriage wasn’t merely a convenience, that it was a companionship two people had to build together, that the sum of mutual experiences is what made it rich and full and good. But somehow, I couldn’t get through to him.

“After a while, I began studying myself. ‘Maybe I’m at fault,’ I thought. ‘Maybe there’s something lacking in me.’

“I went to a doctor. Then I went to a psychiatrist. Then I went to a marriage counselor. The doctor and the psychiatrist said there was nothing wrong with me. I didn’t need treatment or anything. The marriage counselor suggested bringing Dale along for conferences. He didn’t want to go but I insisted until he went with me.

“Nothing helped.

“In many ways he’s a wonderful man. I just don’t think marriage is for him, not a give-and-take marriage anyway. Maybe he needs a wife who will be grateful for any scrap of attention. I’m not like that.

“Dale wants a family, but he doesn’t know how to live a married life. He says he wants to be married, but I guess he doesn’t want to be married to me.”

Before he left for Mexico where he has just put the finishing touches on Sitting Bull, Dale was asked for his version.

Jackie had been awarded separate maintenance of $850 a month for the support of herself and their sixteen-month-old daughter, Rochelle. All Dale would say was, “she asked for a divorce, an’ I told her if that’s what she wanted, it was okay with me. I’ve got nothin’ to say. The marriage just didn’t work.”

The reason it didn’t, according to Kit Carson, Dale’s stand-in and close buddy, is that “the two of ’em weren’t right mates fer each other.

“Dale got married because he wanted a home, a wife and a family. I think he still wants all those things but he’s a man who’s stuck with his nature just like Jackie’s a woman who’s stuck with hers.”

By nature, temperament and background the Robertsons are opposites.

Dale is blunt, honest, stoic, inhibited, proud and unemotional. He has never worn his heart on his sleeve. He had an unhappy first marriage which ended in divorce; he had a rough time getting a break in Hollywood; he was shot up pretty badly during World War II, but he told Jackie very little of all these experiences.

When she tried to thaw him out, when she tried to understand the workings of his mind, to discuss the past and the future, he seemed to rebel. It was as though she were invading his privacy and overstepping the rights of a wife.

“He treated her,” says one of her friends, “as if she were a reporter. And you know how he treats them. Won’t talk to them.

“Of course, I’m Jackie’s friend and I’m taking her side. But honestly, Dale just wasn’t cut out to be a good husband. Hither that, or he married the wrong girl.

“If you love your wife, then you want to spend as much time with her as possible. And with your little daughter.

“Jackie’s very young. Dale is her senior by ten years, at least. During the first year of their marriage he should have been more solicitous.

“Instead he was indifferent. Maybe he thinks it’s unmanly to be in love, a sign of weakness or something. But he really ran the household. And I can tell you this: Jackie really tried to be a good wife. I never heard her complain about anything. And she had good reason.

“Most of their friends were his friends. Practically everything they did, he wanted to do. Dale’s business manager put Jackie on an allowance of $25 a week for spending money. I think Dale got $35 a week. Any time something had to be bought, Jackie had to check with the business manager. It was always his career, his welfare that came first.

“Other girls who are married to actors load up with clothes and big cars and a big house right after the marriage. Not Jackie. Out of her marriage she got a wonderful little baby and a lot of heartache.”

Dale Robertson has never been affectionate or demonstrative. You can tell this in his movie-acting. He would rather act like Gene Autry than Charles Boyer.

His young wife was surprised by this. She believed that gradually Dale would learn to relax, to bare his emotions, to talk to her, to show spontaneous affection.

She had no idea that his desire to become a successful businessman was an obsession. Last year when he told her he intended to invest in the Everlast Laboratories, a company which produces a rubber compound that protects automobile tires from puncture, Jackie said, “Do what you think best, but aren’t you afraid you’re spreading yourself too thin?”

Jackie says now, “I thought he was doing enough, working at the studio and training his horses. And I pointed out that he was putting too many kettles in the fire. He did what he liked. And I certainly hope he succeeds.”

A director who has worked with Dale says, “I have the impression that this fellow is ashamed of being an actor. He tells you that he’s in the game for one reason, money. Maybe. Only I don’t think so.

“I think he likes acting. I think he likes the whole business. If he doesn’t why did he go to night school at the university downtown and take courses in motion picture production? Why has he written three or four scripts?

“My own feeling is that he likes the glamour and the adoration. Secretly, he even likes all the interviews he’s constantly yelling about. Only he won’t admit it.

“He’s got a serious conflict and I guess that’s why he’s a tough man to live with.

“Maybe you don’t understand what I mean. Take a man like Fred Astaire. He’s been retiring from this racket for the last ten years. According to him, every picture he makes is his last. But he keeps coming back. Why? He doesn’t need the money. He’s loaded.

“The reason is that he loves to make motion pictures, and so does Dale Robertson. Don’t let him kid you.”

Dale keeps saying over and over again that he’s pulling out of Hollywood as soon as his contract expires; and while Jackie agreed to go and live with him wherever he wanted to settle, she first wanted to be sure that Dale really loved her and wanted her.

“From the beginning,” she says, “I had the feeling that he regretted our marriage, that he knew in his heart that he had made a mistake and that he was too kind to tell me. I suggested this possibility to him and he said no, that he really cared for me.

“In the months that followed, I prayed that he would prove it by his behavior. I thought that after the separation he would see how bad it was for us to be apart. But no change. Still the same busy, distant, indifferent man.

“When our baby was born he was very happy. I thought that his being a father would change him. He loves our little girl. I know he does but there’s very little demonstration of it.

“l’ve tried everything in the book to make a success of our marriage. Dale is the son of divorced parents, and I didn’t want our child to grow up that way. But there is no use in two people’s living together if they can’t get along.

“I want to say now that I’m not pregnant as the gossip columnists have reported and that there was no third party involved in the failure of our marriage. No other woman—nothing like that.

“I think I could have coped with that, but when a man has fallen out of love with his wife—then it’s just hopeless.

“As a matter of fact, as I look back on it all, it was hopeless to begin with. He just didn’t love me.”

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BARBOUR

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1954

No Comments