Jack Webb: Just The Facts, Ma’am!

Every actor in Hollywood sooner or later finds himself under fire, with the press, his relatives or old pals taking shots at his integrity. The reason is obvious. Success inevitably gives birth to envy, and the urge to find a place on the financial gravy train is an itch few of an actor’s casual friends or members of his family can resist.

Jack Webb, who has become to television what a combination of Alan Ladd and Clark Gable would be to pictures, is no exception.

Here are a few of the accusations not too lately hurled at the creator and star performer of Dragnet. That he is upstaging his friends. That he is too temperamental. That he all but socks on the nose anyone who has the nerve to ask a question about his private life. That he already has decided who the next Mrs. Jack Webb will be.

Because of the stories circulated by Hollywood gossip, a disreputable old bat with a tic in her eye, let’s look at the whole story of Mr. Webb and see what sort of man he really is. Mr. Webb has already been thoroughly worked over by two esteemed journalists in Los Angeles.

They deserve credit for getting straight answers to direct questions from a man a couple of columnists had claimed was impossible to interview. Mr. Hal Humphrey, Radio and TV Editor of the Los Angeles Daily Mirror,had this to say about Mr. Webb’s romantic life: “Webb is understandably nettled at all of the rumors concerning his private life. ‘All I’ve tried to do is entertain the public and grab a little happiness. Naturally, I haven’t any plans for marriage now. There are still nine months to wait before my divorce becomes final. I’ve been going with Dorothy Towne and I may marry her in the future.’ ”

Mr. Humphrey’s reliability as a reporter is not to be questioned. Yet it is impossible to completely verify Jack’s romantic plans. No man can be completely certain that he’s going to wed any girl in nine days, let alone nine months. The facts, however, would seem to confirm that the romance with Dorothy is definitely on. A photographer who took pictures of them dancing together had this to say: “The only two people in Hollywood who never smiled for the camera in my recent experience have been Marilyn Monroe and Jack Webb. A few months back Marilyn began to smile. Now she’s Mrs. DiMaggio. Every time I run into Webb he’s smiling, so I draw my own conclusions.”

Now a quote offered by Jack Webb to Erskine Johnson of the Los Angeles Daily News, in answer to the charge that he’s too temperamental. Said Jack: “Sure, I’ve blown up on the set. I don’t like to be distracted. It happens to everyone in our business. But I don’t feel I’m difficult to get along with. I’ve had the same cameraman and most of the same crew for sixty pictures. I really don’t take myself seriously.”

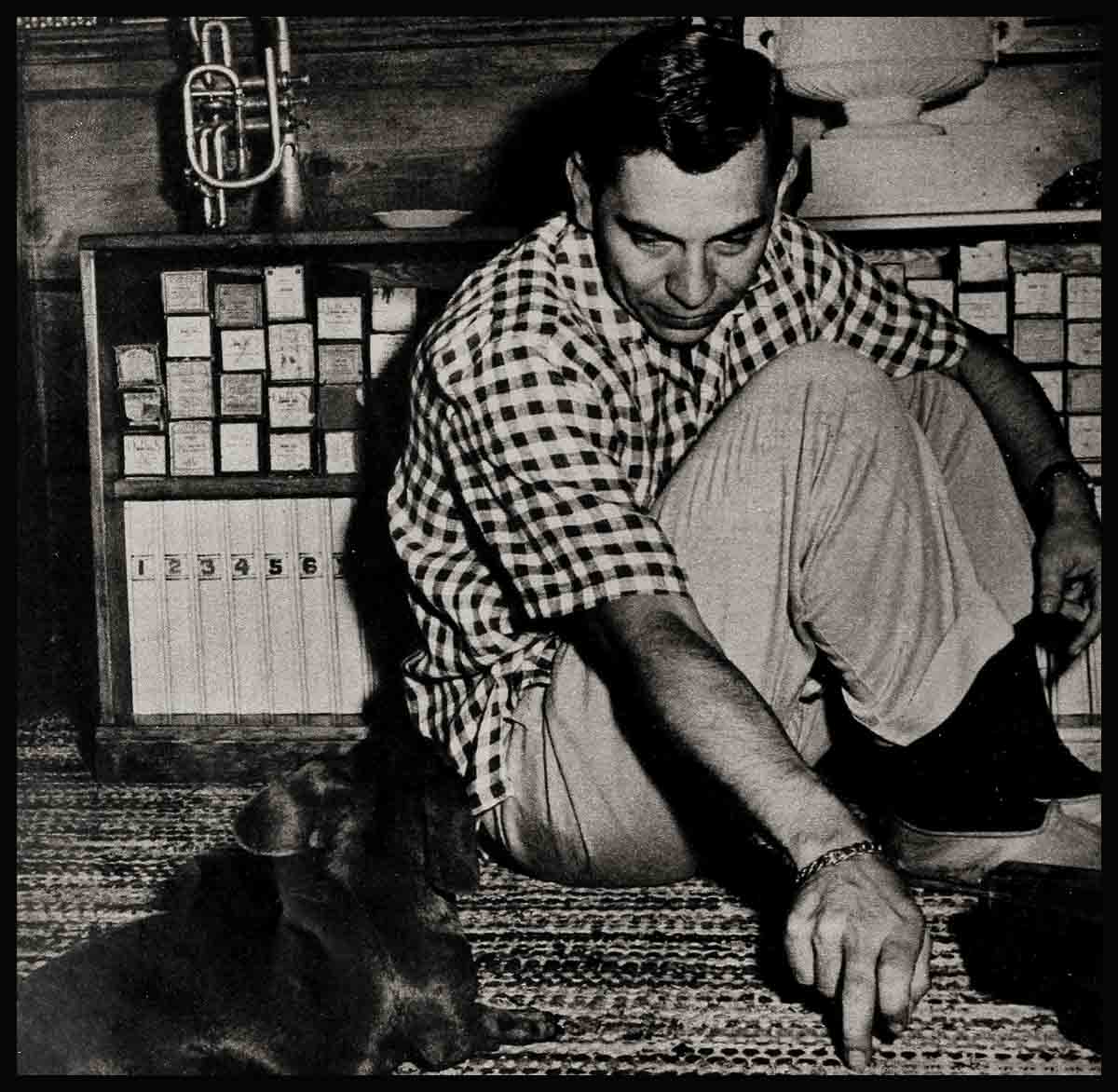

And he doesn’t, although the same attitude does not apply to his work. Sleuthing for MODERN SCREEN, I waited for the formidable Webb in a corner office on the third floor of the Animation building on what the Walt Disney lot is pleased to call Dopey Street. Exactly seven minutes later, the highest rated actor in TV movies walked in, apologized, and said, “Holy cow, we’re not so busy we have to be impolite.” That was a good beginning. As a rule Hollywood actors never beg your pardon unless they are an hour behind schedule. I warmed to this guy immediately.

I asked him: “Do you mind all these imitations of you, like the records, the nightclub character and such?”

“Why should I?” he asked. “I’ll be frank with you. I personally don’t care for the Jones record, for instance. There’s some vulgarity in it. It doesn’t stick with the spirit of the program, which I’d think must be in any real satire. But it’s all right, I guess. Imitation’s the sincerest form of flattery. Of course, they could imitate you right out of the business, but it’s never worked out that way. Take the first good imitation—the record by Stan Freberg. If I couldn’t laugh at that I’d be in a sad way.”

Although he is sometimes referred to as an actor with a crew haircut, Jack Webb’s almost jet black hair is just plain short, not collegiate. Also, he is younger than he appears on the screen. Joe Friday would appear to be forty, smack on the button. Webb is thirty-three years old. He differs from Friday in other ways. His face is much more mobile, his smile more frequent, his justly admired voice freer and less measured.

And on that point I questioned Mr. Webb “I don’t mean to put you on the defensive all the time, but your critics and Dragnet’s charge that this voice business is an over-stylized device.”

Webb rose to the needling, grabbed the hook nicely. “I’ll answer that. In the first place we don’t make Dragnet for the critics. In the second, third and several other places, we haven’t had any demand for a change of pace or tempo from the public. When we do, we’ll start making some changes. The public’s my boss—period.”

That’s unusual. Movie-makers’ attitudes in the past have been that the public consists largely of morons who darned well will take what they’re handed. Webb says, “Not too long ago the public told us to relax a little. Nobody else could have told us unless it would’ be the Los Angeles Police Department. If in one day’s letters I receive as many as fifteen urging one particular reform, and if there are not many dissenters, then there’s a good chance that we may make the change. Last season, you may remember, we made our first pass at humor. It was real quiet humor, the key we thought fitted us best.”

A secretary came in with a script, put it in front of Webb and then handed him a postcard. He turned it over to me, grinning. It was from a girl in the Middle West who expressed the hope that Friday and fiancée would marry so that she, the writer, could baby-sit for them. “That one’s a bit premature,” Webb observed, “but a helpful soul, don’t you think?”

Turning serious again I brought. up the subject, carefully, that has been tossed around among the gossips. Namely that Jack Webb considers himself heaven’s gift to TV and that his opinions and only his are worth anything. His response was not that of a badgered witness.

“Look, Dragnet’s my responsibility. If they don’t like it that way I’m the guy to kick. In fact, I guess I’m the guy to kick for almost anything they don’t like. I’m the director and I help with the writing.”

It might even be said with full candor that Webb is “the works.” Webb is Dragnet and Dragnet is Webb. That is the way he feels about it. “It was a fair little show to begin with. Nothing terribly ambitious. But now I can feel for Dr. Frankenstein. The show’s the monster and I’m the slave. It stuns me a little, what’s happened. But there’s a difference. The good doctor had a pretty wet time after his creation hit its stride. Me, I sort of like it.”

There is little doubt that Jack Webb thoroughly enjoys what he is doing, a strong contrast to most actors who, upon reaching a position in which the public indirectly pays them around $5,000 a week, declare that they hate every second of the time spent exposing themsleves to the cameras. This again puts Webb in a class with men like Alan Ladd and Clark Gable, who actually enjoy acting. It also removes Webb from the class of actors whose small talent has rapidly expanded their hat size.

Still, Jack’s friends wish he could slow up a little. A few sob sisters credit the fact that Dragnet all but consumed Jack’s life for the breakup of his marriage to Julie London Webb last year. This is untrue. The better informed—Webb among them—think he thrives on a fourteen-hour working day, no hobbies and many outside interests.

“It isn’t actually as bad as they say,” Webb contends. “I like to visit friends, have a couple of beers and bat the breeze, and I am interested in a lot of things besides Dragnet and show business.” Two of those include his four-year-old daughter, Stacy, whom he likes to have visit him at the studio, and his almost-two-year-old daughter, Lisa. They are interested in him, too, and so are a lot of other kids. You can’t fool children. They don’t always go for actors who are publicized as their favorites. But one kid said, “Joe Friday—Mr. Webb—he’s real. I went up to him once when he was busy talking to some important people. He walked away from them, gave me his autograph and talked to me a long while. He didn’t have to.”

Jack Webb does a lot of things he doesn’t have to do. One of them is to really worry about the personal welfare of 150 or more people who directly earn their living through Mark VII Productions. They have to eat. They have kids and mortgages on their homes, too.

Webb doesn’t make a big point of this, except to say: “Like some other actor-producers I’m responsible to a lot of people besides myself. So maybe I worry a little and look glum sometimes. That doesn’t mean I’m taking myself too seriously or thinking I’m a crusader. How pompous could I get? We’re entertainers. If a mission sets in along the way, then let’s get it accomplished, and in this case part of that mission is a better understanding of the men who serve on the police force. Take the average policeman. His pay isn’t much. Down here on Main Street a policeman breaks up a barroom brawl and some woman tears the sleeve off his uniform. He’s got to pay for that, and on a salary most of us in Hollywood think we couldn’t live on. So, we’ve got no soapbox, but I’ve wanted to point a program at just that situation. But do you think the Los Angeles Police Department would let us? Absolutely not. They don’t want favors. Not collectively or individually.”

It’s too bad that Jack Webb couldn’t be put in charge of a campaign to dramatize the needs of the courageous and quiet men who enforce our laws silently day in and day out without complaint. Indirectly, he already does that, but if flattered on the subject he’ll only scowl a little and say, “It makes us (he habitually includes his whole crew in speaking of the show) damn happy that most policemen like us and people approve of Joe Friday.”

Delving into Jack’s private life requires a dissolve to a not-too-posh section of Los Angeles where a somewhat frail and asthmatic child was raised by his mother and maternal grandmother because his parents were divorced. Forced by ill health and semi-poverty into rather sedentary pursuits, he became absorbed with painting. Later he turned to a scholarly interest in jazz and jam sessions, a fact which is significant in view of his plan to film a series for TV called Peter Kelly’s Blues. Mr. Kelly will be not unlike the late Bix Beiderbecke who led a brief, intense life during the Hoagy Carmichael college day era.

But that’s a little ahead of the story. Jack Webb had to forego a college education to support his family—the two women who during the worst of his asthma had carried him up hills and stairways. He became a clothing salesman, then switched to a rather aimless and bitter pursuit of acting because of the necessity for more money.

In 1947 Jack married Julie London, after being pleasurably staggered by a pin-up picture of her printed in a magazine during the war. After V-J day they were married. Both took hard the failure of their marriage some three years later. Jack, unlike most of the male favorites in the entertainment world, has refused to discuss the matter with anyone although he is constantly pressed to make public statements.

This writer, who served a little time as a police reporter, tried, then gave up, figuring that Jack Webb is one man who really means it when he passes the word that he doesn’t want his private life or the lives of those around him invaded. Well, you can’t blame him. The memories harbored by the big home in Encino are not too happy. Folks out that way miss him, though. Like over at Love’s Barbeque Restaurant. He used to drop in there now and then for their really famous barbecued beef sandwiches with deep oven baked beans. So did a lot of other stars of both television and the cinema. But Jack Webb’s autographed picture is the only one they framed and hung on the wall.

“I don’t know, though,” one of the waitresses said recently. “We’re remodeling and if he doesn’t get in here pretty soon, we may take him down.” She said it affectionately, though, and I promised to remind Mr. Webb next time I saw him. I’m sure he doesn’t intentionally neglect any of his old cronies, but now he lives way across town in an old-style bungalow kitty-corner from the old Bette Davis home on Franklin Avenue. He lives quietly with his mother and only a few of the closer neighbors know that the fellow who drives up in that sleek white Cadillac convertible is the Joe Friday they see on their television sets.

He’s a pretty average sort of guy whose talent has caught fire in a big way. People will say a lot of things about him simply because he keeps his mouth shut and tends his own affairs in the gaudy, drum-beating world of show business. In trying to show Jack Webb as he really is, you can’t find a better tag line than the quote pried out of him by Hal Humphrey, from whom we swiped a few colorful lines earlier in this yarn.

To wit: “I’m no angel, but I still can look at myself in the mirror when I shave.”—Jack Webb.

THE END

—BY RICHARD MOORE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1954

No Comments