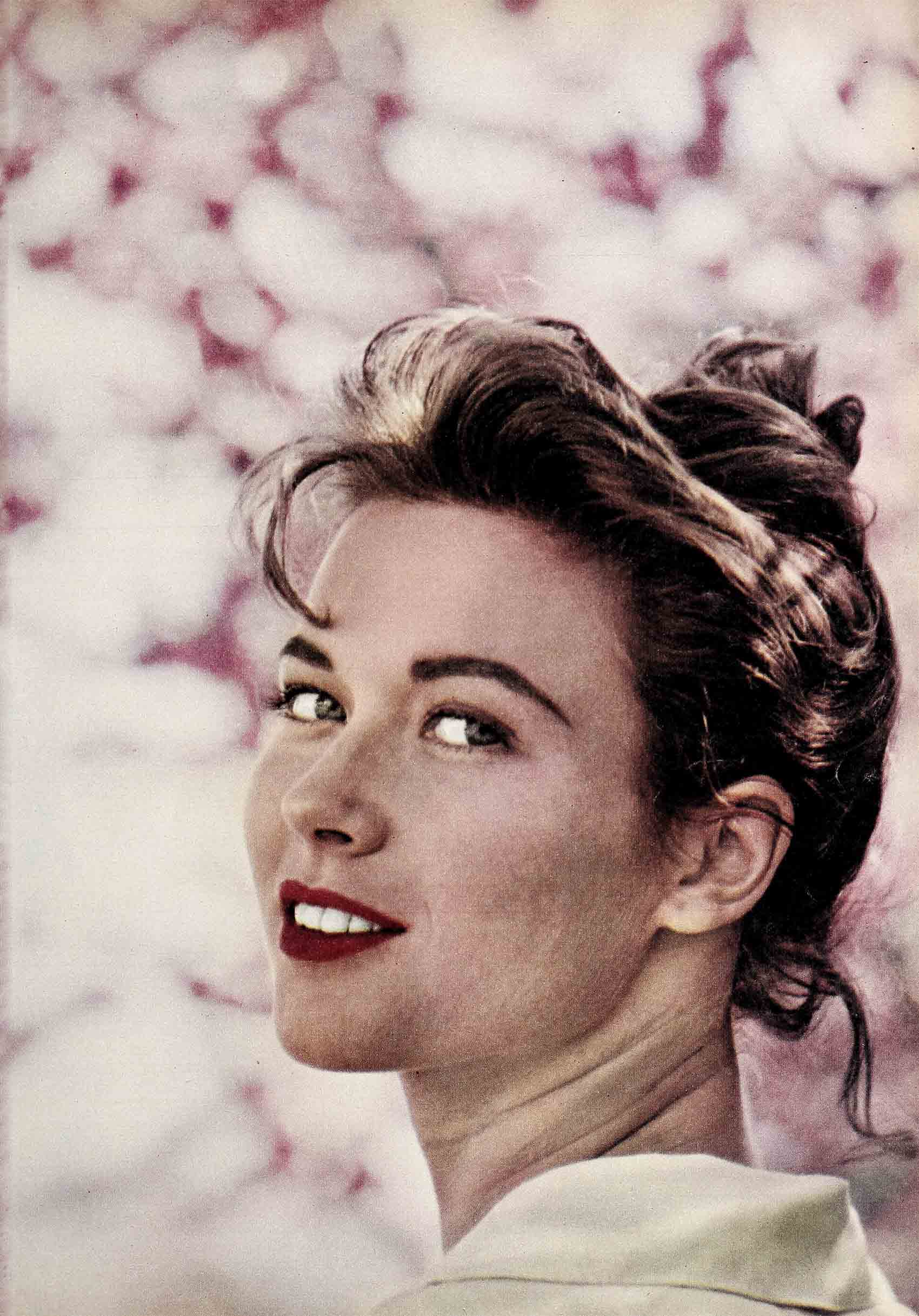

Child Of Sorrow—Gia Scala

The double performance was over for Gia Scala. The long hours in front of the camera at the studio, and the much tougher show she had given every evening for her mother, at home.

Tonight they were previewing the picture that could make her a star. But it almost seemed an anticlimax to this emotional young girl, who had given her finest performance during the seven months she’d watched a dark-haired Irish lady slipping away from her. Her mother, who was so much a part of her success. Her mother, so much a part of Gia.

“. . . Mama, here’s the most wonderful part. We will go to Europe—when you feel better.” . . . “When you get well, we will buy a farm, Mama. We can buy our very own farm . . .”

Chattering, acting, knowing her mother had always been her captive audience, and was making it easier for her now. Just as she’d always been there to listen and to help a sensitive, serious young actress through all of life’s bumps—the large and the small. The part Gia didn’t get. The scene she felt she didn’t play. And always promising the big break, the great moment of triumph, the success that would come. “Wait, Giavonna,” she would say soothingly. “Just wait, my darling. Some day, it will happen. You will see. It will all come . . .”

And now the success Mama had always promised her was here. Tonight M-G-M was previewing “Don’t Go Near the Water,” at the Pantages Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. But just a few blocks away, in a charming modern apartment she and Mama had shared, Gia could think only that her mother had never seen the picture. And how she had wanted to. They were even going to have a private showing for her—but she couldn’t go . . .”

A few days ‘before the preview, cancer had rung down the curtain for forty-year-old Eileen O’Sullivan Scoglio. Leaving a lost and lonely young girl standing on- stage . . .

During those first days Gia Scala lived in a half-world of shadow and light.

“I was going through some things at home . . . afterward . . . and I was walking around the apartment looking for something. I didn’t know what, but something—” Gia broke off. “You know how you get the feeling you wish they had said something they didn’t say. How you just wish they had told you something they didn’t tell.

“I was walking around, just looking, and I picked up this book. I don’t know when I’ve looked at this book on Egyptian art. It was so strange—” Gia had bought the book during her mother’s illness. “I don’t know when she wrote this—I had never seen it before.”

Inside the cover page in a familiar and endearing scrawl her mother had written a note. But when? And why?

“Dear Gia, I love you and I miss you,” the note began. “We will soon be going on location—” Then her mother had gone on, writing of a picture that had been mentioned for Gia, of plans for her future. “And she had. signed it, “Goodbye, My Darling . . . Love, Mama. . . .”

When had her mother written this? I’ll as she was, her first thought had been of Gia. Of her future and her career.

“She was always my biggest fan.” Gia was saying. “My mother always helped me so much. You know, in a sense my mother is me. She is part of all this.”

Part of today—the today that seemed suspended without her. “Probably I will go to New York and see some shows. Everything is ‘probably’ with me now—” Some of Gia’s friends felt she should give up the apartment. “But I don’t want to run away, and in a sense that would be running away, really,” Gia was saying.

Gia was not alone here now. Her pretty sister, Agatha, who was married to a television technician in England, and her infant daughter, Gia Lisa, had spent the last three months here. But soon they would be going home. And what then?

Gia was still too full to talk of it—yet so full she was spilling over with it. A vivid torrent of a girl, Gia Scala. Half Irish and half Italian. Made of bubbles and earth. Warm, sensitive, emotional, and strangely beautiful. “Farfalla” was her mother’s tender nickname for her. “Farfalla”—lItalian for “Butterfly.”

She lay back against the long beige couch talking in her soft musical accent. Filling in much of that which has been unexplained until now. Sometimes the words would rush out—and sometimes they would not come. And it was the poignant story of two people as she talked.

She had been so happy, on that day when she stood on a New York pier, watching for her mother to step off the boat that was bringing her, at long last, from Italy. She had waited so long. It had been a childhood dream come true when she had come to New York, at fifteen, to live with an aunt in Long Island. She was to stay only two years. But now she knew she could never leave—she was going to be an actress, and this was the place to be.

And that night, a joyous Gia took her mother to see the lights of Broadway. “I just couldn’t wait to show her.” They walked through the electric world of animated signs, high as buildings, glittering theater marquees, hustling crowds and honking taxis. Her Giovanna was as beautiful as any of it, her mother thought, watching her green eyes sparkle and her face light up.

They took an apartment on East 55th Street. Gia worked as a reservations clerk for Scandinavian Airlines during the day, and studied with Stella Adler’s drama group at night. She helped pay for her lessons by being a professional “quiz kid.”

“It was all accidental—how I started my ‘television career.’ I was sitting in the audience on Arlene Francis’ show, and she was interviewing me about fashions and Italian clothes. I won a waffle-iron. Then I went on to ‘Name that Tune,’ ‘Stop the Music, and other shows. I won $350 one night—$450—$250—sometimes it was a bad night,” Gia laughs.

Hollywood soon discovered her—“and that was accidental too. I was studying at Stella Adler’s and a pupil of hers took me to his agent. Not for any work, really, because I wanted to finish my course first.” But Universal-International was looking for a young actress with unusual beauty to play Mary Magdalene in an epic planned, and Giovanna was soon enroute to Hollywood to make two tests for the part. “One before she changed—a drunk scene—and one after.”

To Gia seeing herself on film the first time “was a very bad experience. It’s shocking to see yourself on the screen. You don’t believe it’s you. We all have such a different concept of ourselves. I was so depressed.”

Depressed—and sure she would never have a future in the American films. Gia’s mother had remained in New York until they could know the outcome of the test, and when U-I offered Gia a contract, she put in a call to her. “I don’t want to make it,” Gia said.

As she was explaining now, “I just didn’t want to sign. In fact I called my mother long distance twice. I was a little bit frightened. I wanted to be in the theater. Then I thought too, having an accent—”

From across the miles there was strength and assurance. “Stay, Giovanna. Sign. Give yourself a chance. You can do it. You will see.”

“My mother gave me so much encouragement. I used to give up here. Many times. You know you always get discouraged—that’s one of the actor’s trademarks.” Her mother’s happy-go-lucky Irish nature would lift the depression, and her intense faith in Gia would hearten her to stay.

“We had just one room when I started. No furniture of our own. No nothing.” And in a small cubbyhole of an apartment near the studio, Gia Scala fought the weary battle of waiting, wondering, hoping, waiting.

“The waiting—that is the worst. Even though you have a contract and you get paid, that doesn’t mean anything, actually. It’s very hard when you don’t get any parts—and you don’t find your own place where you fit, you know.”

Did her mother like Hollywood?

“She liked it for my sake. She never did really feel at home here. I think it’s hard for people who just live here to feel at home. There is no life really. You’re looking for parts, or trying to get a good part instead of a wrong one.”

It was an excited Gia who came home one day with the joyous announcement that she made a “part” in Rock Hudson’s picture, “All That Heaven Allows.”

“I thought it was the most important thing in my life,” Gia was smiling now. “And I never had even one line. I called the front office for about a month to see if my lines were ready. My lines were never ready. I was just a girl visiting Rock Hudson’s house with my parents in the picture. You could hardly see me—just a few seconds on the screen. But my mother saw me. She thought I was just great.”

Then came “Never Say Goodbye”—“and I had two lines—so that was good. Then I had a whole scene to myself—then I had a part, one of the leads in ‘Four Girls In Town.’ Then ‘The Big Boodle’ with Errol Flynn.” And now other studios were asking to borrow Gia Scala. She was loaned to Columbia for “The Garment Jungle” and to M-G-M for “Tip on a Dead Jockey,” with Robert Taylor.

Her mother—so proud, so happy—would work on Gia’s scrapbook, pasting in every picture printed, every word written about her. And she would wait expectantly every evening for Gia to park her little Austin Healey and come rushing in to give her a colorful account of her day at the studio. “She missed me even when I was gone a little while.”

It was an exciting day when Gia got the lead opposite Glenn Ford in M-G-M’s “Don’t Go Near the Water.” “It was a big thrill—and a little sad, too. Anna Kashfi was to do the part. She became ill, and I was very sad because she is such a lovely girl. Of course it was a wonderful break for me.”

But life, as though balancing the score, was giving with one hand and taking away with the other . . .

Gia’s mother had developed a bad, irritating cough that wouldn’t go away. A concerned Gia persuaded her to have a routine checkup, and X-rays were taken. Gia had to leave for New York and a scheduled appearance on Steve Allen’s NBC-TV show the following Sunday. Mother’s Day.

“I didn’t make it on the show. It was very strange. I kept calling my mother before the show to see how she was. Usually when I was away, you know, we’d phone each other and write. But this time—I couldn’t get her on the phone.

“I just had to talk with Steve Allen on the show, and he is such a nice, easy man to talk to. But I didn’t make it. I don’t know what came over me,” Gia was saying now. A nationwide television audience saw Steve Allen introduce Hollywood’s bright new star, and saw her rush off the stage. “I said a few words, and then I just couldn’t go on. I don’t know what happened. It was subconscious. I was terribly worried. I’d kept trying to call, and no answer . . .

“And that day,” Gia added slowly, “she was found by a friend of mine lying there on the floor, and with such pain . . .”

When she returned to Hollywood, her mother underwent lung surgery at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital. And Dr. Bert H. Cotton, specialist in heart and lung surgery, was faced with the sad duty of finding the right words to tell Gia her mother had a malignancy that was inoperable. To prepare her for the months ahead. Knowing how close Gia and her mother were, the surgeon was concerned, lest Gia have a breakdown. Worried how this would affect her.

He asked Gia to meet him at the Los Feliz Brown Derby, not far from the hospital. “The doctor called me and said he didn’t want to talk to me on the phone. He invited me for a cup of coffee. Then he told me, and I didn’t believe it. I—mean, you know—what are words?”

She just couldn’t believe her mother wasn’t going to live. This had happened too fast—they had been too close. “Now is there any chance?” Gia would say over and over—after the surgeon had explained there was none.

The night Gia Scala finally accepted it she made headlines in the papers with a traffic accident. She was charged with driving while intoxicated. This was not true and the charges were dismissed. But the accident happened—sadly enough—after a toast Gia had taken with the doctor and her mother—to celebrate her mother’s belief that she was getting well.

Desperately wanting to give her mother the world—all the beauty of the world—whatever happiness there was to give—Gia took her to the sunny shores of Hawaii. It was all the enchantment Gia and her mother had often envisioned, when they’d planned some day to go. “It’s so beautiful, it hurt,” Gia was remembering now, fingering color slides of her mother, loaded down with leis, that were taken over there.

“She was a very strong woman, a wonderful woman, with great heart. But Mother had really five days out of the trip that were good. She was quite ill there.”

Fighting even harder not to let Gia know she knew. Theirs was a double performance to the last. Her mother acting for Gia—and Gia giving a performance she would probably never equal again.

“Gia played the game all the way,” a close friend says. “It was just wonderful to watch her. She gave a performance every night at home. She kept her mother laughing and smiling.”

A weary girl, working all day on the set at U-I, getting no sleep at night, would come in from the studio, go into her mother’s bedroom and start clowning. Repeating her scene for the day, playing every character—in a western, yet. “Oh, Gia, you’re so crazy!” her mother would say, loving every moment of it.

Gia had always told her she had pneumonia. “I said that from the first.” But later, she was to learn that a priest in Honolulu, believing one of her faith should know, told Gia’s mother what she had probably suspected before. “But she always knew what she had in a way . . . and she fought until the last.”

Her mother had wanted Gia to go on working.

Gia turned down any role, however important, that would take her on location away from her mother. But she made “In The Middle of the Street,” with Audie Murphy at U-I during the final weeks of her mother’s illness. And how she got through the picture, Gia doesn’t know now. “I don’t know how I was there, believe me. Because I couldn’t sleep—I haven’t been able to sleep for so long. But I think it was the best work I’ve done. Because, after a while, my mother was so glad I was working. And the studio was so nice during production, to give me a car to go see her.

“My mother wanted me to go on with my career. I went to a premiere, ‘Raintree County,’ and actually I wasn’t feeling like going at all. But she was in the hospital and she had a television set. She said, ‘Oh, you go—I’ll get to see you on television.’ ” And she had been so proud, watching her Giovanna there with Earl Holliman, being interviewed, along with Hollywood’s most famous stars.

Later, their close friend, Dore Freeman, of M-G-M’s publicity still department, brought a picture of Gia at the premiere to her mother’s hospital room, adding it to the many colored stills of Gia and Glenn Ford from “Don’t Go Near the Water,” that he’d brought and which surrounded her bed. Her mother would look at the stills lovingly, proudly.

All her thoughts were of Gia and of her future. To the doctor her mother said, “I must live, because Gia is not ready to be by herself in this. I must live for a few more years.” And two days before she left she gave a sacred trust to their good friend, Dore Freeman, who had been so thoughtful and helpful, always standing by: “Will you take care of my Gia for me?”

But when Gia Scala’s mother left—it was with a smile on her face, as though in some way known only to God she knew that for Gia the show would go on. And that her Giovanna would not be alone—would never be alone—or without hope.

But for the sensitive, talented girl who had longed to find her own place in life—who had come thousands of miles to a strange country, mastered a strange language, and reached stardom—during these first days there seemed, now, no place.

As she puts it, “You’re looking for something. You call it a place. You try to find it in people. I realize now you don’t fit any place. I mean, really—only with your own family—”

Gia’s father was getting older and would never want to leave Italy. Her pretty sister Agatha and her little namesake, Gia Lisa, would soon be going back to England. “I don’t want to get too used to you—it will be too hard to let you go,” Gia would tell her sister.

“It’s awful to be alone and not to be able to think for somebody,” Gia said. “You must do things for somebody to be happier. You have to give of yourself. Now what do I do? Not thinking of anybody else—”

But out of the void of emptiness, of time suspended, Gia was beginning to know now what she would do. To realize there was somebody else. Someone who had given so much of herself to Gia and her career. Her mother, with her gay Irish philosophy and her tender, unshakeable faith.

“I don’t know about leaving this apartment. I don’t like running away, and that would be running away, really,” Gia was saying slowly now. “Sure, there are things you remember, and they remind you, but . . .”

Her mother’s last thoughts, her last words—the letter she’d written—were all for Gia’s future.

“I want to work,” Gia was saying now. “I want to work, work, work!”

Her place, Gia realized, was here. This was her place. This was where she belonged. And this was their future—her mother’s future too. There was the feeling, that as long as she worked here—she would never be alone.

“There’s more than just—the person. They don’t just—disappear” Gia was saying slowly. “My mother helped me so much. In a sense she is me. She is part of all of this. She lives for me . . .”

And she would live. As long as her Giovanna created happiness for others. As long as her star lasted. As long as the name of Gia Scala was known.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1958