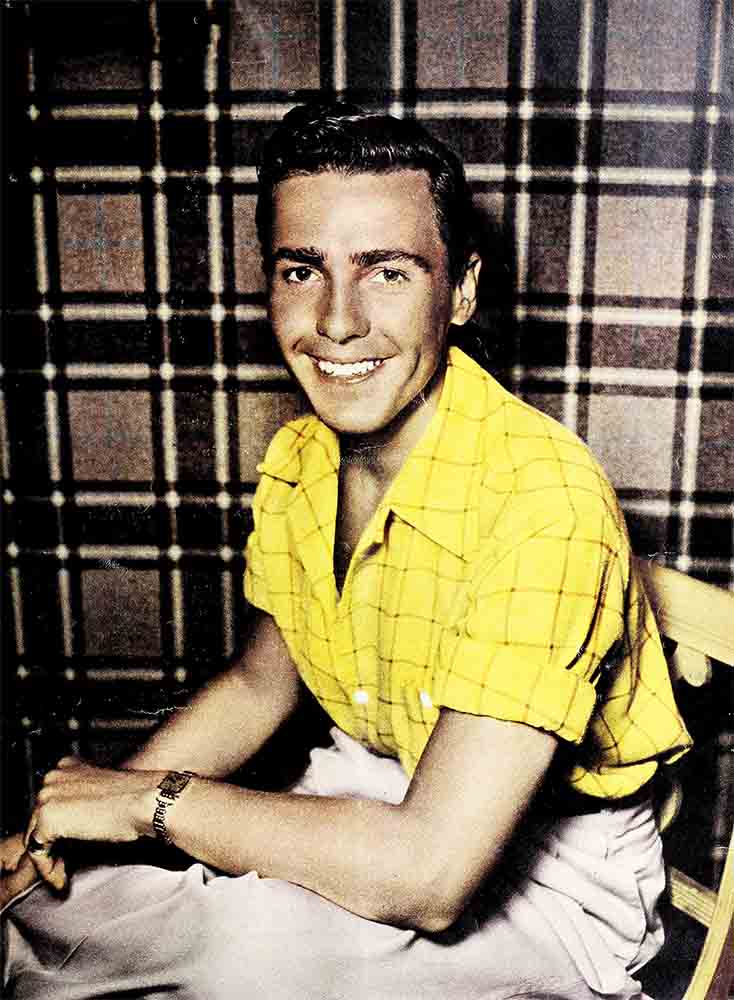

Eyeful Of William Eythe

Time was when William John Joseph Eythe was the loneliest six-footer at the Twentieth Century-Fox studio. Out of all that bustling city, modestly known as the lot, there were only three people he knew—and he didn’t know them very well.

That was two years ago and it isn’t lonely on the lot any more for Bill, who is no longer a newcomer but is an established fact—one of the facts that gives Fox stockholders that smug expression. The two years have been crowded with learning things—not only about his job but about life in general and Hollywood in particular.

AUDIO BOOK

He has discovered, and certainly to his own surprise, that he doesn’t prefer actresses to other women. This was something of a blow, he doesn’t mind telling you. He had expected to be crazy about actresses. He has also discovered that he doesn’t like night clubs or large parties or parlor games and that he is terrified of meeting motion-picture executives socially. And—here’s news—he thinks he knows what is wrong with most Hollywood marriages.

He has just rented himself a house, high, high above the Sunset Strip, where he can see the ocean, Los Angeles City Hail and also get a nice bird’s-eye view of his neighbors who seem very interesting. It has four rooms and a bath and he says the furnishings and decorations are purely of the “hodge-podge school—no sense to any of it.” He is pleased, however, with the bedroom which is done in flamboyant red because if there is anything Bill likes better than most other things it is the color red applied almost anywhere. The owner of the apartment he has just vacated was pretty appalled to discover that Bill had pasted red plaid wallpaper on every available space.

The particular lure of this house (aside from the advantages of gazing at the City Hall and spying on neighbors) is a large fireplace situated in a room which is nearly all glass and makes him feel as if he were living in an aquarium. He can curtain the glass (in red) he thinks, install his piano, his records, books and the few really fine paintings he owns—and then he can sort of “wrap it around him” and be lonely and cozy and thoughtful. A cleaning woman disturbs him only a little bit, coming in twice a week. And he knows a fine cook who will “do for him” when he entertains an occasional “large party” of six. He wouldn’t dream of inviting more than six people to his house at once. Too confusing.

The cook is a patient soul who endures, without very much complaint, Bill’s invasion of the kitchen just as the guests are arriving, to stick his fingers in the stew and the pudding, to lick, to frown and to remark “Howzabout another bay leaf in that one?” He thinks he is a pretty good cook himself (beef Stroganoff is his specialty), but he never feels efficient enough to try to get everything ready at once for guests. So he employs a cook—and kibitzes.

He says he was “conditioned” to playing second fiddle early in life so it doesn’t bother him now, even with the cook. He was born in Mars, Pennsylvania, and if you haven’t heard of Mars Bill thinks you should be ashamed of yourself because it was the home of the famous “Dutch” Eythe—“you know—that guy who won All-American football honors when he played halfback for Carnegie Tech!” He was Bill’s brother.

Bill was different. When he was about eight “Peter Rabbit” came into his life. It was a play and his school class was giving it and his mother probably didn’t know what she was doing to her little boy when she browbeat him into acting in the thing. Because he never got over it. Not that he wanted to act, you understand. He wanted to be that man who bossed everything and ordered everyone around—the director. From that time on he wore his cap backward, carried a box with a funnel stuck in the front of it and commandeered every kid in the neighborhood to “act” in front of his “camera.” One day he ran out of Tarzans and was forced to essay the role himself. He fell out of a tree and was laid up for seven months with two fractured legs. It gave him time to think, he says now.

All this thought turned to an abandoned barn he knew about. As soon as he could hobble he turned it into a theater where he produced “Eythe Productions.” He wrote, produced and directed his plays with no profit to himself or his company whatever. “It probably wasn’t even fun for anyone but me,” he admits cheerfully.

In 1937 he entered Carnegie Tech, scene of his brother’s athletic triumphs, and confounded everyone by turning his entire attention to the drama school. His chief interest was, as always, in sets and costumes, but they always seemed to be running short of actors and he was always absentmindedly consenting to add a performance to his other duties. When he graduated he was mildly astonished to find that he had acted in more than eighty productions. In the meantime, by way of paying his expenses through college, he had lectured on astronomy at a planetarium (he memorized the lecture and if anyone had asked him an intelligent question about the stars he would have died on the spot). He had also produced musical fashion shows at a department store by way of selling ladies’ clothes. (He says these were terrible.)

After that he settled down to acting and his story is pretty routine—summer stock, bits on Broadway, fair parts away from Broadway and so on until he got the role of the neurotic young officer in Steinbeck’s “The Moon Is Down.” He gave a good performance but he took a terrible beating. A “superior officer” was required to cuff him, to bring him out of his hysteria. He did it so thoroughly that when the play was tried out in Baltimore, Eythe’s left eardrum was punctured. Later on, at a performance in New York, his right eardrum suffered the same shattering. He was almost completely deaf for months.

And after that he came to Hollywood. He hitchhiked a ride with a friend whose wife had had to stay home until their dog had pups. “Good old pups!” Bill reminisces. After that—well there was that contract and that loneliness. There were the roles in “The Ox-Bow Incident,” “The Song Of Bernadette,” “The Eve Of St. Mark,” “Wilson,” “Wing And A Prayer,” and now, suddenly, as he goes into “The Royal Scandal” with Tallulah Bankhead, he’s famous. He’s bewildered. He’s trying to make up his mind about things. He has already made it up about several things!

Marriage, for instance: “Trouble is, they try to do it with props! Hollywood is the loneliest place in the world and when two people can’t bear it any longer, they decide to get married. They think that if they get a house and maybe a woolly dog to lie on the hearthrug, all they have to do is marry and move in there and everything will be fine. They forget that they are individuals, with separate tastes and ambitions, with vanity and sensitive feelings and selfishness and with no time to themselves to try to smooth out any difficulties. All the chintz curtains and log fires in the world won’t help them.”

Actresses: “They have to spend so much time trying to seem to be something that they are not they don’t have enough time to be what they are.” He paused, after this ambitious statement, and struggled, “I mean—if a woman has to spend that much time on her appearance and on being seen in the right places and making the right effect—well, then she sometimes doesn’t develop mentally and emotionally. The girls here are devastatingly beautiful, but some of them are shells—sort of. They don’t have that inner quality of—heart.”

He likes one Hollywood girl though, he admits. Her name is Carol Andrews and she is a stock player at Twentieth. He takes her out and sees her whenever it’s possible. “She hasn’t got that way yet,” he explains and that’s all he will say about it.

He wishes he could be “sophisticated” and explains hastily that by that he doesn’t mean witty, flip and overwise. He means he’d like to be at ease in any situation (which he is not), would like to be able to adjust himself to people and circumstances without having to struggle. He guesses that he “just isn’t social.” Large parties terrify him, chiefly because he is afraid he’ll encounter “an executive.” “Executives are always sizing you up and judging you,” he says. He dislikes night clubs because nothing of any consequence ever happens in them—“No one even finishes a sentence.”

He detests Hollywood gossip and he is impatient with what he calls “prattle”—brittle chatter about nothing. He wishes that people would talk “objectively” but admits that he finds it difficult to do himself. He likes actors if they are interested in acting as a fine profession and not merely trying to exploit an easy way to fame and fortune. He loves to argue. He won’t hold it against you if you make him mad in an argument either. He gets over it immediately. Sometimes he makes other people mad—and they don’t get over it. He regrets this.

He composes music. Some of it is pretty good—very interesting, modern in mood.

He is extravagant—mostly about clothes, books and food. California delights him because a man can wear all kinds of vividly colored sports clothes, summer and winter, and no one will take the slightest notice of him. He’s a pushover for gay sports shirts, jackets, sweaters and plaid socks. Can’t pass a shop window containing any such thing without going inside to buy. He thinks, ruefully, that maybe these extravagances of his will prevent his marrying—although he hopes not. Maybe he couldn’t support a wife in the style to which she was accustomed and also support his wardrobe in the style to which he is rapidly becoming accustomed.

He doesn’t own any evening clothes and the only time he really had to wear them (he had to take Anne Baxter to a premiere), he rented them and he says he looked very funny in them.

He played in stock with Ruth Chatterton. She encouraged and advised him about his future. He remembers that with gratitude. He is grateful, too, to Mary Morris, a teacher at Carnegie Tech, who did a lot for him. Henry King, who directed “Bernadette” and “Wilson,” really needled him into making a needed effort, he thinks. He yearns to meet the author Marcia Davenport, who wrote two of his favorite books, “Of Lena Geyer” and “Valley Of Decision.”

If the milkman, bus driver or gateman at the studio is rude to him, it upsets him for hours. “What have I done? What sort of heel am I?” he wails. He broods until something happens to take his mind off this deplorable occurrence. A kind word and he bounces up like a friendly puppy.

He is impatient with possessions (except books) and the two he treasures are a tiny brass elephant with an upturned trunk, which he thinks has brought him luck, and one of the socks he wore in his first play. His Irish grandmother taught him to put out. milk for the leprechauns when he was a tot and sometimes he has a notion to fill a saucer at night now. But—he’d feel silly—so he doesn’t. Still . . .

He’s a bit proud of the tuft of chin whiskers he has grown for “The Royal Scandal.” They’re not exactly lush, but they’re there and they are his very own.

He wishes women wouldn’t wear short evening frocks—“they look so unfinished.” And he likes them to have that well-scrubbed look. But he’s afraid that women don’t care a bit what he wishes in these matters.

He loves his parents as much as the next man and he wouldn’t live with them for anything. “Too many American parents forget to wean their children,” he opines. “Ours had the good sense to help us to be on our own, when we were of age. Oh! Did I tell you about the time my mother ‘ran interference’ for my brother Dutch on the football field? It was a high-school game, of course. She got so excited that she ran right along the edge of the field, when he was carrying the ball, yelling, ‘Do it for your mother, Dutch! Do it for your mother!’ That was funny and everyone was amused. But a lot of parents try to ‘run interference’ for their kids after they’re grown up.”

At the moment, finding himself surprisingly in the money, he is torn between two ambitions. When the war is over he wants to travel, go everywhere and see everything. He has a sneaking hunch that the girl of his dreams lives in England and that if he can just get over there he’ll find her. But he also has plans for a “cultural center” in Beverly Hills—and those plans aren’t too ephemeral. Already there is interest and a promise of financial backing. “A theater, an art gallery, a library,” he says, dreamily, “right in the center of everything, where everyone can enjoy it. It would be a monument!”

Other young men have had to choose between monuments and wanderlust. Wonder how young Eythe will decide!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1945

AUDIO BOOK