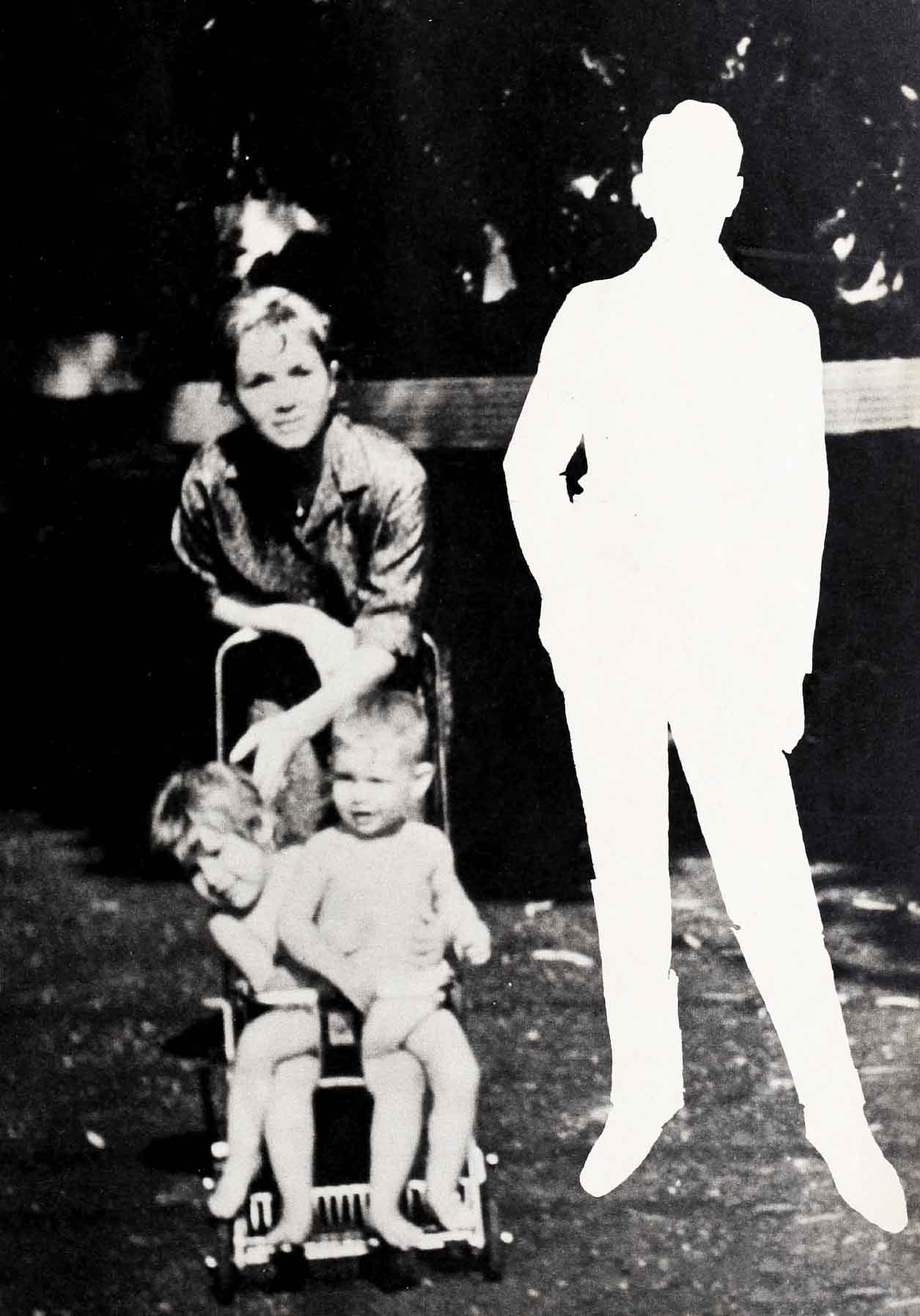

Exclusive Family Picture

“Don’t frown, Franny,” her mother called, and just the sound of her girlhood name made Debbie laugh. She turned her head, so the sun would no longer be in her eyes, and then her mother clicked the shutter. Later, when the pictures were developed, they’d go in her family album. She could look at them and remember the way Todd and Carrie squealed with delight over their Hawaiian costumes. They could bring back the carefree vacation when there’d been no secrets to hide except maybe a surprise gift for Todd. And no decisions to make. It was so different now.

Now, everything seemed to be pushing her toward a decision. And in her heart, though she might have doubts and second thoughts, she knew she had made it. It was only natural to have second thoughts about a decision as important as marriage. And she had to be sure, so sure. “Especially the second time,” she said.

She took the family album down from the shelf and spread it open on the coffee table to add the new photographs her mother had taken of her and the children. In a way, because this time she had to be sure—for the children even more than for herself—she could be grateful that, for a little while longer, the decision must stay a secret.

Yet, it was not an easy secret to keep.

Always questions

It was like that other time—how long ago it seemed—when she’d stepped off a plane in San Francisco and the reporters, pushing aside the members of her family who’d come to meet her, had shouted, “When’s the wedding? Are you engaged or not? What’s with you and Eddie Fisher, anyway?”

Then she had fought back the tears of indecision and frustration. “I . . . don’t . . . know,” she said slowly. “I don’t know.”

Yet, in her heart, despite all the ups and downs of the engagement, she had known, just as she did now. Only she couldn’t answer them. She and Eddie were engaged for a year before they married and looking back on it now, she knew that it had been a mistake. They hadn’t given their love a chance to grow in private. She knew now that you needed to be alone, to have the privacy to get to know the person you loved, before you announced your love to the world. And for all the waiting, she’d gone into something for which she wasn’t equipped. The Mary Frances Reynolds who’d been raised a clean-living homebody couldn’t permit her bridegroom Eddie to hand out keys to their home. She got them all back. Jazz trumpeters sleeping it off on the living-room sofa, she said, was going too far.

So now, even if she knew her answer to the “When are you marrying?” “Who are you marrying?” she hugged her secret close to her.

Sometimes, the question was asked with only the lift of an eyebrow. Like the man at the studio who’d asked. grinning, “Have fun in New York?” He’d looked at her knowingly, as if he was sure he could see through those dates she’d had on her trip to New York and wanted her to know that she wasn’t fooling him. His grin seemed to say that he knew those other dates were just a camouflage, that he knew nothing was changed between her and Harry Karl.

Sometimes the questions were spoken out loud. “When’s the wedding?” they persisted. And after she and the children and her mother had come back from a trip with Harry to Palm Springs and, later, made a trip to Las Vegas with him, they pushed her even further, adding, “December?”

But she couldn’t answer them. Harry’s divorce from Joan Cohn didn’t become final until October, and she couldn’t say anything until then. She had always believed strongly in observing that kind of convention, and she had never been the kind to grow impatient with the year-long waiting period of a California divorce and rush off to a wedding in Mexico or Las Vegas.

And then there were the whispered speculations. Like the woman who’d been walking her dog along Benedict Canyon and had heard voices coming from the backyard of No. 906. There was a “For Sale” sign on the front lawn and the rambling, two-story Spanish style house was supposed to be deserted. The woman had investigated, making her way to where she could peer through the trees and shrubbery that shielded the rear garden. An old blanket was spread on the grass and there was Debbie, with little Carrie and Todd and her mother, having a picnic. The woman had tip-toed away. The scene seemed so private. She had stumbled on them outdoors, in a garden, and yet they seemed so unguarded, so at ease and at home. It was like peeping through a window into a family’s house and seeing the people who belonged there relaxing.

The woman had meant to respect this privacy. She had meant to tell only one friend. And, yet, somehow the rumor had spread and the next day, when it was reported that Harry Karl had bought that house, nothing could stop the gossip. People began calling it Debbie’s Honeymoon House. Debbie herself called it her “dream house.” A columnist quoted her as saying that, though Harry had handled all the negotiations, the property was in her name.

The house is so stately, so elegant, people said, it belongs to the old days in Hollywood. You’d need an army of servants to run it. Those who thought they knew Debbie said it wasn’t the kind of place she’d be happy in.

And then an architect had confided that Harry was talking of tearing down the house and building a smaller, more compact one on the almost-priceless site. That would be more the thing for Debbie, people said; she would want a more homey and comfortable place.

A family-size place. For first to consider, were Carrie and Todd. They had to be happy in any house she lived in, in any decision she made.

Seated on the couch, the family album on the low table in front of her, she turned to an empty page and began to add the new pictures. She smiled, remembering how happy the children had been the day they were taken.

Harry gave so much

Carrie and Todd were getting to know Harry. They seemed to really like him, to look forward to his visits. Her parents, too, seemed to approve of him. He’d been like one of the family at her brother’s wedding, and he’d still fitted in easily and naturally, even though his gift had been diamonds, at the simple hamburger party her mother had given her for her birthday. And he was so thoughtful. Only a man like Harry would file away in his mind a casually mentioned date and then, some months later, remember it with a birthday party for her mother and all the family at L’Escoffier.

Harry seemed to give so much, and in a way that obligated nobody. It was almost as if he were grateful to you for allowing him the pleasure of giving.

She could never forget the look on his face the day when she had reversed things and given him a gift. There had been surprise, confusion, almost an awkwardness as to how to act when someone else was doing the giving. With a little pang, she realized how much Harry had given all his life and how little he’d gotten in return.

He’d been all thumbs as he tried to open the package without tearing the ribbon. “Here,” she laughed, “let me help.” Finally, he lifted the lid of the little white box to find a pair of Star of David cuff links studded with diamonds.

“Oh, they’re beautiful,” he said, not even realizing, at first, that each cuff link opened up. That had been the best surprise. She had shown him how, inside one of the cuff links she’d put a tiny portrait of her two children and, in the other, a picture of herself.

Still smiling, Debbie added the final picture of the children to the album and then twisted the cap back on the bottle of glue. Then, as she always did when she added new pictures to the album, she began turning the pages back to other older pictures.

There was a picture of her and Eddie, snapped by a night-club photographer at his Cocoanut Grove opening, their second date. Neither of them had dated very much before they met each other and then, suddenly, in a lovely, bewildering time, they were falling in love for the first time. There were other pictures of them, when they’d joined the gang at Janie Powell’s pool. She looked at their faces, close together, laughing up out of the pages.

And there was their wedding picture. Not the one she’d planned on, not the one of herself in a long flowing gown with the train carefully arranged by the floor and Eddie, in a formal suit, standing by her side.

Somehow, after being engaged for a year, after planning so long on a big, beautiful wedding, they had ended up with a hectic, last-minute affair at Grossinger’s. They decided only a couple of days before and then they’d telephoned her mother in California. There was no time for fittings for a dress. Her mother, without explaining why, so as not to give away the secret, managed to borrow the air-mailed the dress to her.

Still it had been a lovely wedding. She had come down the stairway in the cottage where Jennie Grossinger’s daughter lived and had caught her breath at the sight of the giant mums in tall vases and the gold and russet leaves that filled the room. A string trio began to play “Moonlight and Roses,” and, for a moment, she had faltered. “No, please,” she’d whispered. “Could they play the ‘Wedding March?’”

And then, with fifty guests looking on, County Judge Lawrence Cooke had married them. She tried to speak her marriage vows in a clear voice but, in the double-ring ceremony, she was so nervous that, without realizing it, she put Eddie’s ring on the wrong hand. But it was a borrowed ring and, later, she bought him another. After the wedding, someone told her that when, finally they were man and wife and Eddie took her in his arms and kissed her, she had emitted a sigh that everyone in the room heard. She didn’t remember it.

There, in pictures, she saw the story of their marriage. The brief honeymoon. Their first house. Carrie as a baby and then before long, little Todd Emanuel. They were a complete family now.

It all looked so perfect. Yet, had the camera lied? Had she somehow lied to herself, smiling through those years but really playacting at marriage? Perhaps it was true, after all, that she had shut her eyes to the trouble and clung to an image of the marriage as she wanted it to be. Now that it was all over, she could no longer deliberately forget the times she and Eddie had appeared in public in frozen attitudes that showed their unhappiness . . . the times they’d gone to friends for advice . . . and even to psychologists and to a marriage counselor. That had been a year before the breakup, a year before her marriage ended in the very place it had begun, in Grossinger’s, when Eddie and Liz went there together.

Recently, on Decoration Day weekend, she, too, had gone back to Grossinger’s. “Jennie Grossinger is my friend,” she had told people when they looked at her wonderingly. Yet, before deciding on a new marriage, it had been a good place to go and face the truth about her old love once and for all.

She flipped quickly past the pictures of herself taken shortly after Eddie had left her. The camera had caught, too well, the drawn face and the eyes rimmed with dark circles. No longer smiling, she continued to turn the pages of the album.

After the divorce

There were pictures of the men she had met and dated after the divorce. Before her marriage, she had never been one to date just for the sake of going out. And, though she was anxious to begin a new life, she still felt the same way, she had to like the man or not go out at all. Yet strangely enough, once she was free, she found that there were not very many men around who were eligible, especially when they had to measure up as a prospective husband for her and a father for Carrie and Todd, too.

“The next man I marry,” she has vowed to friends, “will be one hundred percent good for my children or I’ll stay single.”

For a while, there was Bob Neal. They’d had good times together. Yet Bob was a perennial beau, probably having too much fun changing Hollywood beauties with the seasons to really want to settle down.

On trips to New York, she saw Walter Troutman. On a trip to Hawaii, she’d dated Tab Hunter, but he was a friend and only that.

And then there was Glenn Ford. They’d enjoyed working together in “It Started With a Kiss,” and they had fun together on dates off the set. He took her to the Foreign Press Awards dinner and it was a memorable evening. They ran into Maria Schell there. No matter how lightly she may have taken their dates, it was hard not to be hurt a little when she learned that, all the time Glenn was seeing her, he had been secretly and deeply interested in Maria.

And then there was Harry Karl. A kind and generous man, respected and admired by everybody, he began by dating Debbie casually. At that time, he was caught up in a romance with Joan Cohn and, eventually, married her. It was hard to say what had happened, but, on their honeymoon across the country, they suddenly called a halt to the marriage and Harry came back to Hollywood a free man—except that he would have to wait a year for his California divorce to be final.

Was that when she began to see Harry in a new and serious light, during that time when she missed him? For it was hard to deny that she had missed him. His constancy. His tenderness. His Rock of Gibraltar strength in the face of his troubles, his unflinching loyalty and devotion that, so far, no younger man had offered.

“I have everything—everything beyond what I ever dreamed of years ago,” she insisted to people, pointing to her home, her children, her successful career.

All of it she’d earned the hard way, throwing herself into work while the humiliation of Eddie’s rejection seemed to strip her in public. She worked and played thirty benefits in ninety days, and took such care of her children that no one was surprised, later, to hear how she slept on the floor next to Todd’s bed, one night, when he had the croup. Fingernails cut short, she kept removing the phlegm from his mouth on the three hour shifts she alternated with the nurse. To offers of help she said stubbornly, “I have to do it myself.”

She tried to bury her problems in work, until she collapsed with a blood clot and an ambulance had to be called. “What are you trying to prove?” her boss at Twentieth asked. “That all bachelor girls die young?”

But what she earned, was the admiration of millions of Americans who love guts.

A state trooper whizzed up beside her speeding car, his clenched fist up.

“Oh, oh, here comes a ticket,” she thought.

But he was only trying to tell her something. “Keep it up, baby,” he shouted. “We’re all pulling for you.” The fist went up again, a tribute to a girl who’d handled herself right through the most humiliating—that life can hand out, and he roared off.

She says now, “I learned two things from disaster. One is to expect trouble, because you’re sure to get it, and you can pick up the pieces faster when it comes. I don’t mean be bitter—just fatalistic about life. The second thing, the real secret, is to put a new value on yourself. I’d always been my parents’ daughter or Eddie’s wife, now I was me! What was I worth? Nothing, it seemed at first. I had to prove myself all over again.” Which she did—as an actress, a person, and a woman.

For she knew that a career could be up one week and down the next month. She had seen it happen to Eddie. And, anyway, public admiration was no substitute for the stronger, more lasting love of a husband.

A mature love this time. To young love she had given her heart, her hopes and her life. In return, it gave her disillusionment and heartache, embarrassing her before the entire world. With Harry it would be different. With Harry, her heart would be safe.

She looked at the photographs of Harry. They didn’t really do him justice; he was much younger than he looked in pictures, much handsomer.

She turned, again, to the last pages and the new pictures of Carrie and Todd, studying them closely. They both had brown eyes, like Eddie, but people said the shape of their eyes was like her own. There was Carrie, her arms spread wide open, as if she were welcoming the world. She was like that, always full of talk and laughter, always learning a new little dance or song and bursting to show it off. Her mother said she was just like Debbie had been at her age. Todd was a happy little child, too, but quieter than Carrie, more placid.

She could remember the look, only a few short weeks ago, in his deep brown eyes. It hurt and he was scared. She turned from the bed where he lay, to the doctor. Todd had to have an operation, he told her. It was a minor operation and yet . . . how could any operation be “minor”? For a moment she’d felt panic. She couldn’t make this decision by herself. She knew what she must do.

She’d rushed to the phone; she had to tell Eddie, to ask his advice. But though she called every place she could think of, she couldn’t get in touch with him.

It was only later, when it was all over, that she had managed to reach Eddie and he had come flying to Todd’s bedside. How grateful she had felt to Harry during that awful time. He was so solid, so dependable. It was so good to have someone like that to lean on.

Friends would no longer have to say, “Debbie, without a steady man around, is a sad sight—but Lord, she’s admirable.” They could stop telling how this tiny woman, alone now with her children, keeps a loaded 38 by her bedside. The gun was real, but it was also a symbol. If she married Harry, he would take care of her.

There were pages to be filled

He’d be that way as a father, too. He’d be someone the children could always count on, could always come to for good sensible advice. She remembered how Todd had clung to his hand during that trip to Palm Springs. It was a good image to keep in her mind as she went over and over her decision.

Before putting the album away she turned back the pages for one last look at the picture of herself and Eddie on their wedding day. Her hopes had been so high then; the future had stretched ahead of them so bright and shining. And yet, somehow, somewhere, it had all gone wrong.

The picture blurred before her and she shut her eyes, as if to shut out the doubts and fears that came flooding back. Did she really dare to risk her heart again? Was it possible, she wondered, that she could make the same mistake a second time? She didn’t dare think of it; and yet she must.

Finally, with a sigh, she closed the album firmly, as if closing the book on the the past. There were pages in it yet to be filled, she knew. Now it was time to think about the future.

—MILT JOHNSON

SEE DEBBIE IN PAR.S “THE RAT RACE” AND “PLEASURE OF HIS COMPANY.” DON’T MISS HER SPECIALS ON ABC-TV. HEAR HER SING ON DOT. AND WATCH FOR HER IN “PEPE” FOR COLUMBIA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1960