Elsa Maxwell’s Book Of Etiquette

Etiquette is a lot of bosh and nonsense. The old -fashioned stereotyped brand I mean, of course—the unspeakably stupid kind of etiquette which decrees only a fork shaped thus and so can be used for salad and only a spoon of a certain size and shape is proper for ice cream and so on, ad nauseam. The myriad rules about what is and what isn’t the proper silverware were invented to sell cutlery. They’re a racket, like so many other manifestos of etiquette.

Hollywood stars, bless them, are less and less subject to the dusty, dated dicta which have been perpetuated too long by succeeding self-appointed arbiters of good manners. Again and again I find the stars defying the text-book theories of etiquette to practice the true manners which come from the heart.

For instance, etiquette books still hold that a gentleman never, never allows a lady to walk on the outside of any pedestrian thoroughfare. This used to make sense. When roads were filthy with mud and slops which carriage wheels splashed and when there was an added danger of runaway horses and horses tethered at hitching posts, certainly it would have been less than chivalrous for a man to walk anywhere but on the outside of the way.

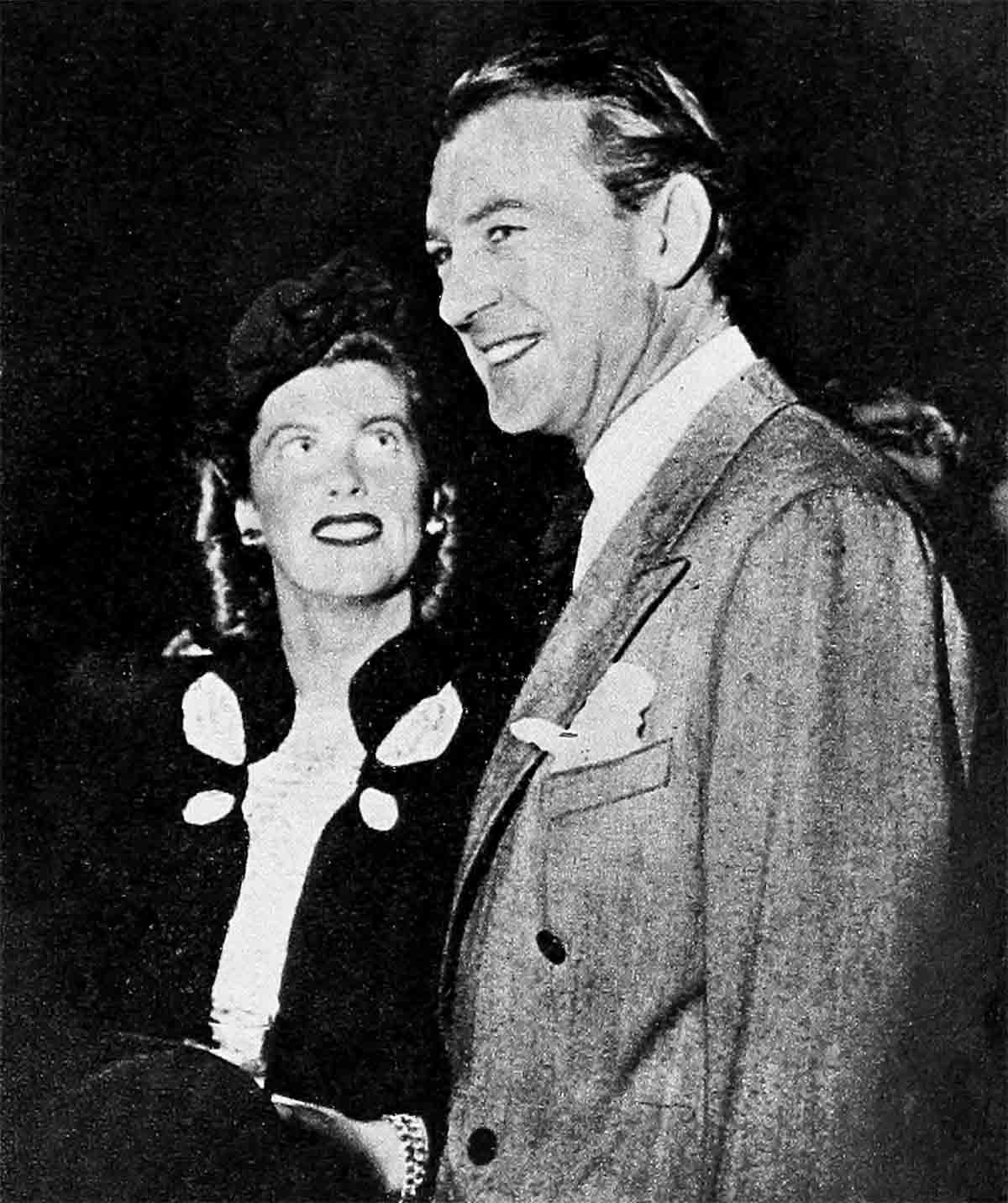

Today, however. Vine Street in Hollywood—along with most thoroughfares—is neatly paved and safely devoid of equine traffic. Consequently it presents no dangers. Thus, only the other day Gary Cooper walked quite a distance at my left. Not because he isn’t a gentleman. On the contrary! Because he was too much of a gentleman to interrupt what I was saying while he switched to my other side. Ordinarily Gary would walk on the outside; simply because it long has been the custom for men to do this. However, these days—in my book—only a man less a gentleman than Gary would insist upon walking on the outside every step of the way irrespective of any and all circumstances.

Essentially to be a lady or a gentleman is to be primarily kind and secondarily inconspicuous. We’re inconspicuous, of course, when we control our emotions and practice such obvious niceties of behavior as . . .

Not pushing or shoving . . .

Not interrupting . . .

Not talking or laughing too loud . . .

Not making scenes . . .

Not topping another’s story . . .

Not forcing our company upon others . . .

Not forcing our opinions upon others . . .

Not dressing in an ostentatious manner . . .

Not boasting of possessions or accomplishments.

To show you exactly what I mean let us compare, say, Errol Flynn and Ronald Colman. Both are British, intelligent and well off. Errol is indisputably brilliant, stimulating and amusing. Invariably I find myself liking Errol even while I disapprove of the things he does and doesn’t do. Not in my wildest imagination, however, would I call Errol a gentleman. Ronnie, on the other hand, is a very great gentleman. Before he married Benita—who is a very great lady—he never was known to take too many cocktails, to get into fist fights, to contribute in any way to newspaper headlines or community gossip. As a bachelor he lived and worked quietly—just as he does now that his life is enriched by a wife and baby daughter whom he loves deeply but without any public display.

The longer I live the more convinced I am that kindness is the essential ingredient of social desirability and true manners an outward manifestation of an innate desire to please. Which explains how a certain assistant cameraman is a greater gentleman than the star I watched him photographing the other day. This in spite of the fact that the star has all the advantages—college and a good prep school behind him, plus the income with which his screen success endows him. The cameraman, however, truly enjoys helping others. He is quick to notice when a star needs her make-up, when an old extra has no chair, when the noise of a fan is distracting to the director—and to correct all these things in a friendly way. Therefore he rarely fails to do the right thing even though he does not always do it with orthodox form. The star, of course, is thoroughly versed in the proper form. But because his gestures are something with which he shows off instead of something whereby he expresses deference they are virtually worthless.

Analyze every polite phrase, every polite custom and you will find an expression or an act of consideration. “How do you do?” denotes interest in a person even as you greet him. “Thank you” shows appreciation. “Good morning” is in a sense an invocation, asking that the morning be good to the one you are greeting or leaving. We stand when a much older person enters a room in evidence of our respect for their greater years and presumably greater wisdom. We give our seat in a crowded room or bus or train to an older person because he is less able to stand than we are. Or a man gives his seat to a woman of any age for the same reason. We make an effort to look as if we are enjoying ourselves at a party so our host and hostess will feel their efforts to please us have been successful. We consider the prices on the menu when our young man takes us out so we will not strain his finances. And we conceal the fact that we do this to save his masculine pride.

The reasons for many customs have changed with time. However, kindness remains the motivation behind them. For instance, in the days of family and neighborhood feuds and vendettas it was customary for a gentleman always and even for a woman to remove the right glove before shaking hands. To indicate no weapon was concealed. Nowadays—although it is no longer obligatory—the right glove is sometimes removed because it, presumably, is less clean to the touch than the hand it has protected. A hostess is still served first. In the days of the Borgias it was done to show guests that the food was not poisoned. Today it enables a hostess to indicate how and when the food is to be eaten.

Have you, by chance, ever stopped to analyze the word “etiquette”? It means, as its very sound implies, ticket. Once upon a time in France if a bundle had a label or ticket tied to its neck declaring its contents it passed without examination. Gradually the word came to denote the unwritten code of honor by which professional men like lawyers and doctors conducted themselves in order to uphold the dignity of their professions. And finally it came to describe the rules of graciousness which we all practise in order to uphold the dignity of the human race. In other words, our manners are our ticket of admission into the family of other kind, thoughtful people who realize that we could not all live together in this world unless we showed each other proper consideration.

Which brings me—pleasantly—to Gene Tierney. During the time Gene’s husband was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, she proved a delightful hostess when she served tea to other Army wives in the jerry-built bungalow she furnished out of second-hand stores. She is an equally delightful hostess today when she entertains stars and members of the international set at al fresco parties in the patio of her California home. The explanation of her success in these widely divergent settings is simple. She has a gift for making others feel important. When men and women feel important they expand. Stimulating conversation and good fun result. A party becomes a success. I wish you could see Gene at a party, observe the warmth with which she moves forward to meet every new guest, the warm way she says, “I’m so glad you could come!”

Frequently I compare Gene with girls who have had greater social opportunities—girls like Brenda Frazier Kelly and Barbara Hutton Grant. Always it is the others who suffer by comparison.

Roz Russell is another bright light in my Hollywood etiquette roster. . . .

A big house on a hill, good schools . . . these privileges are things Roz always has taken in her stride. They unquestionably have helped her to social courage. However, in the final analysis, Roz isn’t the great lady she so unquestionably is because of any of this; rather because she’s so interested in people and so eager to have them know it. She abides by no set rules, Roz. Her actions vary with the occasion. There’s just one thing she never is deliberately—elegant! Frequently, however, she is unconsciously elegant—in another and far, far bigger sense of the word. The way she was last summer even though she went about too thin with her usual vibrant voice sounding tired. She was elegant then, let me explain, because of the magnificent way she had worked overtime for the political party in which she believed, for the boys in hospitals, and for Sister Kenny’s infantile paralysis treatment:

It’s Roz’s interest in others that makes her such a great hostess. She may not have seen you for a year and she may have met you only once or twice before, but she’ll remember that you love cucumber sandwiches or that you prefer sherry to cocktails.

Gone is the stupid notion that a lady is a female who, at the least provocation, reaches for smelling salts. . . .

In further proof of this I offer Joan Fontaine. Joan, carefully reared and convent bred, has worked in hospitals as a nurse’s aide, bathed strangers who hadn’t been bathed for too long, stood for trying hours in psychiatric wards, emptied bedpans. And has never called quits. That may not be the old notion of a lady. But it’s a swell approximation of a thoroughbred!

Naturally, since woman’s place in the world has changed, feminine manners and customs have changed too. A girl no longer has to sit back and eat her heart out lest a boy thinks she is running after him. If her club is giving a dance or if she has tickets for the theater it is fitting and proper for her to ask a boy she knows to go with her. I am not, let me make it very clear, suggesting girls pursue boys. Not because this isn’t etiquette. Because it isn’t smart. Basically men appear not to have changed at all. They still, at least, like to think themselves the pursuers.

Hollywood’s two Swedish importations—Garbo and Ingrid Bergman—very definitely rate as ladies. Neither shines in any gay cafe set. But both have great dignity, are charming among their friends, and Ingrid is gracious in public. The latter is not true of Garbo because shyness is a phobia with her and she forgets her manners when confronted by strangers.

You’ll be surprised, perhaps, that I also place Dorothy Lamour high in my list of Hollywood ladies. But don’t be misled by the fact that Dorothy is portrayed strictly in her screen character in all publicity. Her producers would not permit anything else. Actually, Mrs. William Ross Howard is a sweet old-fashioned girl—the furthest possible hail from the sarong siren the public knows as Dorothy Lamour.

There’s something else besides being a lady, of course. There’s greatness. . . .

Bette Davis couldn’t be said to be a great lady. Neither could it be denied that she is one. She is a genius; one of the greatest actresses on the screen, one of the greatest personalities in the film colony. Consequently she is a law unto herself. She has little time or interest for most of the superficial things by which many rich and famous women set great store. But she will spend hours—after difficult days in the studio—working for the Hollywood Canteen. Also she’ll blow her lines, hold up production and risk irritating both her producer and director because, with her quick perception, she notices that some bit player is off in his performance and believes he will do better with another try. She’s incalculable and, over all, great!

Hollywood today enjoys considerable social prestige—not only in America but the world over. This began, years ago, when Mary Bickford and Douglas Fairbanks of Pickfair entertained the professors and crowned heads, the scientists and maharajahs, the musicians and humanitarians, the artists and politicians they met on their triumphal travels. There could have been no more perfect ambassadors for the film colony. For Doug, brilliant and magnetic, in a way was Robin Hood off the screen as well as on. And Mary, although less socially inclined, has always been a wise and charming woman.

Above all, refuse to be terrorized by the edicts of etiquette books. Simply be thoughtful and kind and you will, like the stars, themselves, pass, with flying colors, in any society worthy of the name.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1945