Better To Be Certain Than Sorry

The floodlights at the Los Angeles airport were whiskered with rain, and little streams of water trickled down the field. It was the day after Thanksgiving, 1953, but it didn’t seem as though anyone could be thankful for anything on such a day.

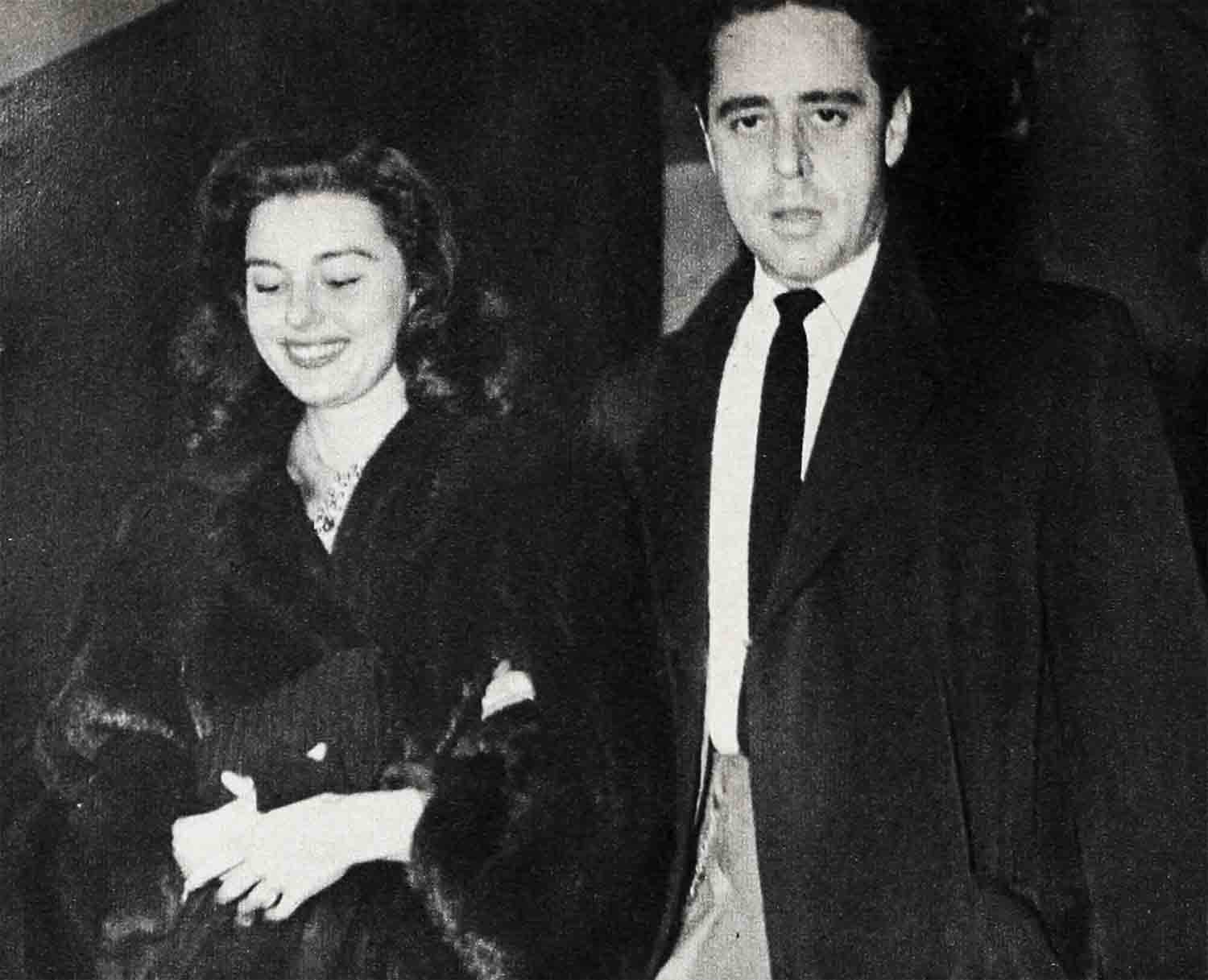

Elaine Stewart, her coat drenched and- her feet wet and numb, stood in the center of the air terminal signing soggy autograph books. On her right side was the handsome young man who had fought for and won the honor of escorting her to the airport. On her left were the three equally-handsome young men who had lost—and had driven to the airport anyway.

They glared at each other.

Elaine Stewart didn’t notice. She smiled and laughed and thanked her fans, but it was automatic. The smile seemed wired to her face. Her eyes were bright with fever, and she was so exhausted that she hardly knew—or cared—that it was raining.

“Here’s something for the plane.” The handsome young man who had won handed her a package tied with red ribbon. It was quickly joined by packages done up in green, pink, and blue ribbons.

Elaine fumbled with the packages, and.a magazine slipped from her arms. It was a copy of PHOTOPLAY that she had bought and hadn’t had a chance to read, a copy that called her “The Most Popular Girl in Town.”

Being the most popular girl in town—when the town is Hollywood—means a spotlighted premiere one night and Ciro’s the next. For Elaine, it means changing escorts and evening dresses seven times each week. It means “living it up,” “having a real George time,” even though her day may have begun at dawn and another will begin at the same time tomorrow. Being: the most popular girl in town can mean excitement, thrills, plaudits, a soaring career and—exhaustion.

To Elaine Stewart, living up to her hard-won title had meant losing ten pounds and narrowly missing pneumonia. It had meant the kind of weariness, physical and emotional, that she had never dreamed possible. It had meant sitting quietly one day long enough to evaluate the life she was leading. And finally, it had meant searching for a big, firm rock that she could cling to, a rock that wouldn’t teeter and roll in the Hollywood currents.

Elaine was slipping away from her work in “Brigadoon,” away from Hollywood that wet November day to see just what of real value life might hold for her. Frankly, she had met a man, and like so many women before her, she wanted to find out if everything she believed about him was true.

She had walked and talked and danced with him for three days only, and no one but the telephone operators knew of his existence or of the nightly phone calls from St. Louis.

“St Louis, Missouri calling. Mr. Curt Ray wishes to speak to Miss Elaine Stewart.”

The telephone operator couldn’t know—no one could, not even Elaine—what those calls were beginning to mean to her.

The airplane moved into place. Elaine said her good-byes to her escorts, climbed aboard and settled back. As the plane winged eastward, her thoughts were on Curt Ray, the man who would be waiting to meet her in St. Louis.

At the St. Louis airport, a man stood in the darkness and looked up at the sky. A tall man with dark eyes and dark hair and the faintest trace of a drawl in his voice. Curt Ray. Radio executive and announcer. Son of a lumber king. Soft-spoken southern gentleman. He lit another cigarette and looked at the sky again and waited. Waited patiently. The glow from his cigarette lighted the touch of grey at his temples. Just a stroke of grey, but it was enough to remind him that he was thirty-seven years old and that the years for get- ting a wife and starting the family he had always hoped for were slipping by. Curt had waited a long time—waited until he had matured and grown wise. He must be sure, he told himself. And she, she must also be sure.

From high above his head the roar of airplane motors broke into his thoughts. He crushed out his cigarette and turned in the direction of the sound. It seemed to take the plane forever to circle and land.

Elaine was the first person out. The fever still showed in her face and she looked small and lost on the big windswept field.

Curt walked to meet her. For the first time in three months, they were together.

The beginning was last August on a Friday. Elaine flew into St. Louis on a tour for her picture, “Take the High Ground.” An M-G-M official took her arm, escorted her to a car, and said, “You’re going on a radio show.” There was no rehearsal for the show. She was driven to the radio station; she was on the air; and Curt—as the man in charge of the show—was beside her. After the show he bought her a cup of coffee and took her back to her hotel, and the next morning there were flowers.

Roses. Elaine’s favorite flowers. “He couldn’t have known they were my favorites,” Elaine has said. “But he did. He seemed to know lots of little things about me from the start.”

He took her to dinner and out dancing that night and brought her back to the hotel at 11:30—a scandalously late hour because she had interviews the next day, Sunday. That night he took her dancing again, and Monday morning he drove her to the airport.

St. Louis was just one of sixty cities—just one three-day stop—and she was on to Omaha, Des Moines, and the whole state of Texas.

In her one day in Omaha, Elaine went hrough the same hectic program of interviews and posing for photographs that she had in St. Louis. But she went back to her hotel early. And Curt called.

“I guess I was expecting it,” she had said. “But I didn’t know it would make me feel so good. Sort of as though I was homesick before the call came without realizing it.”

He called every night after that, called to Fort Wayne and Fort Worth and Dallas and Amarillo. He managed to get a copy of her schedule on the tour and when he didn’t know what hotel she was staying in, he called them all until he found her.

The nightly calls followed her to Hollywood. Wonderful, exciting calls that touched on astrology and the way an ocean looks by moonlight, her career and how many stars there are in the sky, his career and the smell of roses.

Now, for the two people standing on the St. Louis airfield, there was no need for phone calls. For two weeks—weeks that Elaine had begged from the studio—there was no need for phone calls.

Curt touched her tired, drawn face with his hand. Then he led her to his car.

“Excuse me, darling,” he said. “I’ll be right back.”

He was gone for fifteen minutes. When he came back, he slipped into the driver’s seat and started the motor.

“I just called my brother,” he said. “In Kentucky. We’re going there—tonight.”

The car moved smoothly forward over the new concrete road that led to rolling hills and the deep rich grass of Kentucky.

“Somehow he knew,” Elaine said when she returned, “just as he knew so many things, that I was too exhausted for a city.”

“Most of that four-hour drive, I was asleep. I remember Curt waking me for a hamburger and coffee somewhere in Illinois. And I kept thinking how big America was and how wild it looked at night. In Kentucky—near the border—we went up a hill, and I woke up again, feeling as excited as if it was the night before Christmas and I was expecting my first real doll.”

The sky was turning blue and orange and the car was covered with dew when they came to the lake where Curt’s brother has a pinewood cottage. Asa, Curt’s brother, and his wife, Rebecca, were standing in the doorway. The living room was all made of pine, and a fire was roaring in the fireplace, a perfect setting in which to learn about a man’s family—and about the man.

That afternoon, and every day afterward, Curt and Elaine strolled along the lake, step by step beginning to know each other, gradually beginning to understand each other’s similarities—and differences. They walked for miles and talked for hours. They laughed together. And were serious. They were like two people memorizing the verses—line by line—of a rare and precious book of poems.

The week that Curt and Elaine spent in St. Louis was filled with dancing and quiet dinners, more long talks, Curt’s job. Elaine was really seeing him for the first time in his own way of life.

Two weeks—even two magic weeks—must end. And Elaine flew back to California. The Elaine Stewart who returned was a different person. The feverish flush had left her cheeks, and her eyes were no longer tense and tired. She had gained back seven of the pounds she had lost. And, most important, she had gained real insight into the man, Curt Ray.

And then people began to ask why the “most popular girl in town” wasn’t being seen in the gay spots. Was she spending her evenings at home for a reason?

Elaine herself was evasive. She knew that she was staying home because she wanted time to evaluate the two telling weeks she’d just been through. She wanted to take the memories out one by one, hold them up to the light of solitude. She wanted to think—about Curt Ray. And about the other men in her life.

There were rumors that Elaine had returned with an engagement ring. On that score she was evasive too. “I’m not wearing a ring,” she said firmly. “And when I do wear one, I’ll be engaged and busy and planning a wedding. Until then, I might have a ring and I might not, but . . .”

In the meantime the gossip columns were worrying the matter of Elaine’s heart like a terrier with a bone. Wrote Walter Winchell: “St. Louis columns insist movie star Elaine Stewart is that way over Radio Executive Curt Ray, but we hear her heart-throblem is named Johnny Grant.”

A second column said she was practically engaged to Travis Kleefeld, and a third named Gig Young as her “show stopper.”

And Elaine Stewart continued to bide her time, to say little, and to meditate.

When there was an effort made to pin her down on that two-week trip, to trick her into saying that it must have been important, she was forthright. No tricks were needed, after all. “I was tired and exhausted,” she put it. “I needed a place to rest and someone to help give me back my strength. Curt is the only person I know with enough strength for two, and then some extra. I have always looked for Curt’s qualities in a man—his gentleness, his understanding, his rich sense of humor, the way he belongs with any group.”

But when she spoke, she omitted the most important reason of all for her having gone to visit Curt: a mature desire to get acquainted with him, as himself, and as the man who might one day be her husband.

Even if her heart had already determined that she was, indeed, to be Curt’s wife, she wasn’t ready to say so. Not yet.

“Love must have dignity and privacy,” Elaine says. “So I guess if I were in love, I’d try to hide the fact as long as possible, until I was certain that the romance was real—and forever.”

And in St. Louis a tall man was also staying home at night. A tall man who also wanted to be certain.

How long would it take them? As long as it has to, in order to be sure, says Elaine. “Any girl should have a sincere appreciation of her man, and she must be honest with him. Any man must be made to feel that he is important, at least as important as a career. And that’s why it’ll probably be at least a year before I can be really sure. Right now, I’m at the end of three years of terribly hard work. Three years—and I’ve finally gotten my big break. I’ll have to work like a beaver for another year before I can devote half my time to a man.”

Though Elaine has tapered off on her dating, she has not become a recluse. But she’s made it clear that she isn’t going to sacrifice the real and basic joys of life just to retain her popularity title. In this period of making up her mind she continues to see her old friends. Johnny Grant still stops by on Saturday afternoons with a couple of quarts of ice cream and some chocolate syrup. The flowers from her admirers continue to arrive. And the telephone rings all the time.

And to Elaine, this is all a logical part of gaining perspective on Curt’s place in her scheme of things. For she can’t evaluate him in a vacuum. She knows that she must visualize him in terms not only of her future dreams, but of the current experiences and the potential romances in her life.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1954