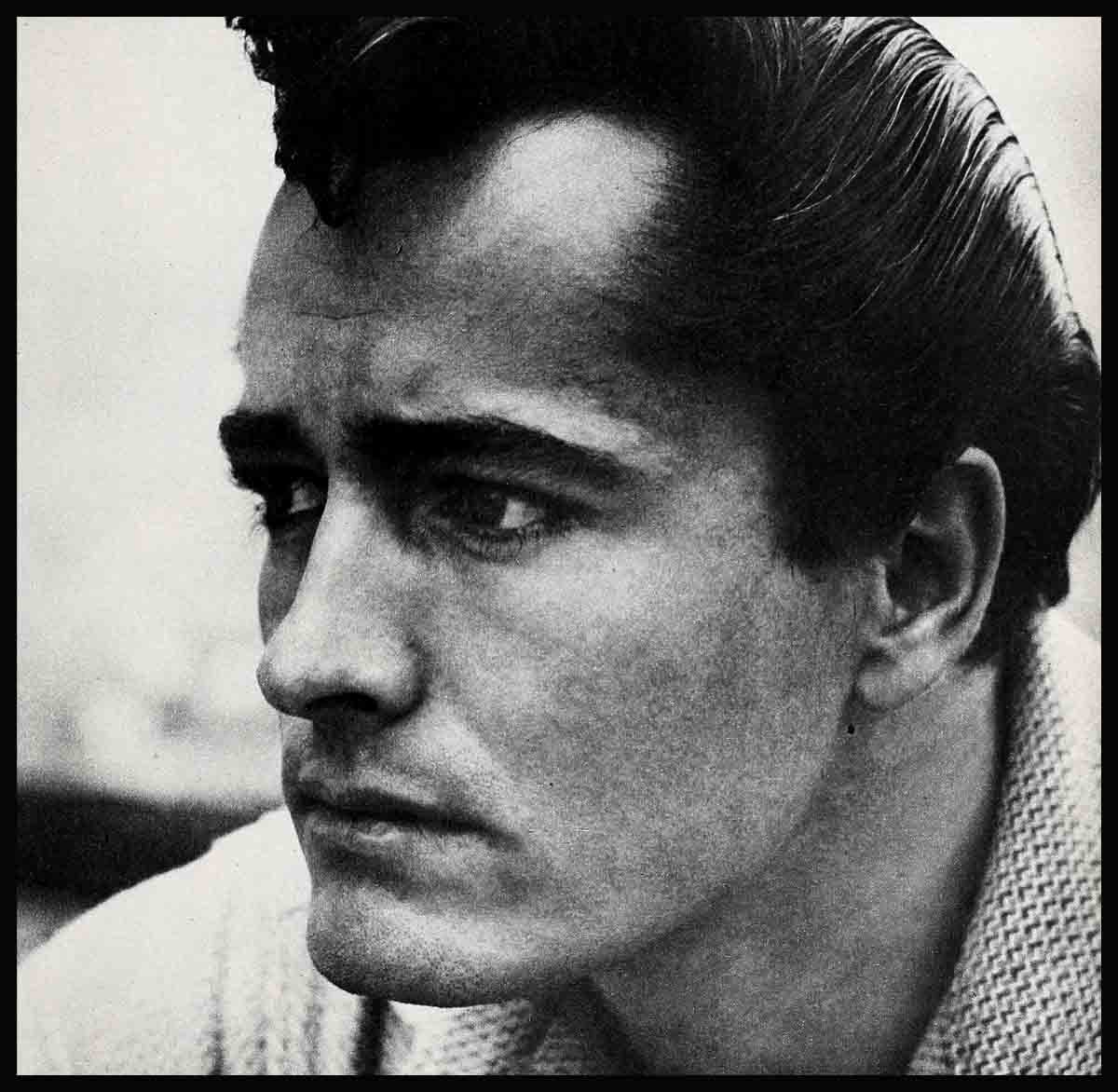

The Truth Behind John Derek’s Bust-Up

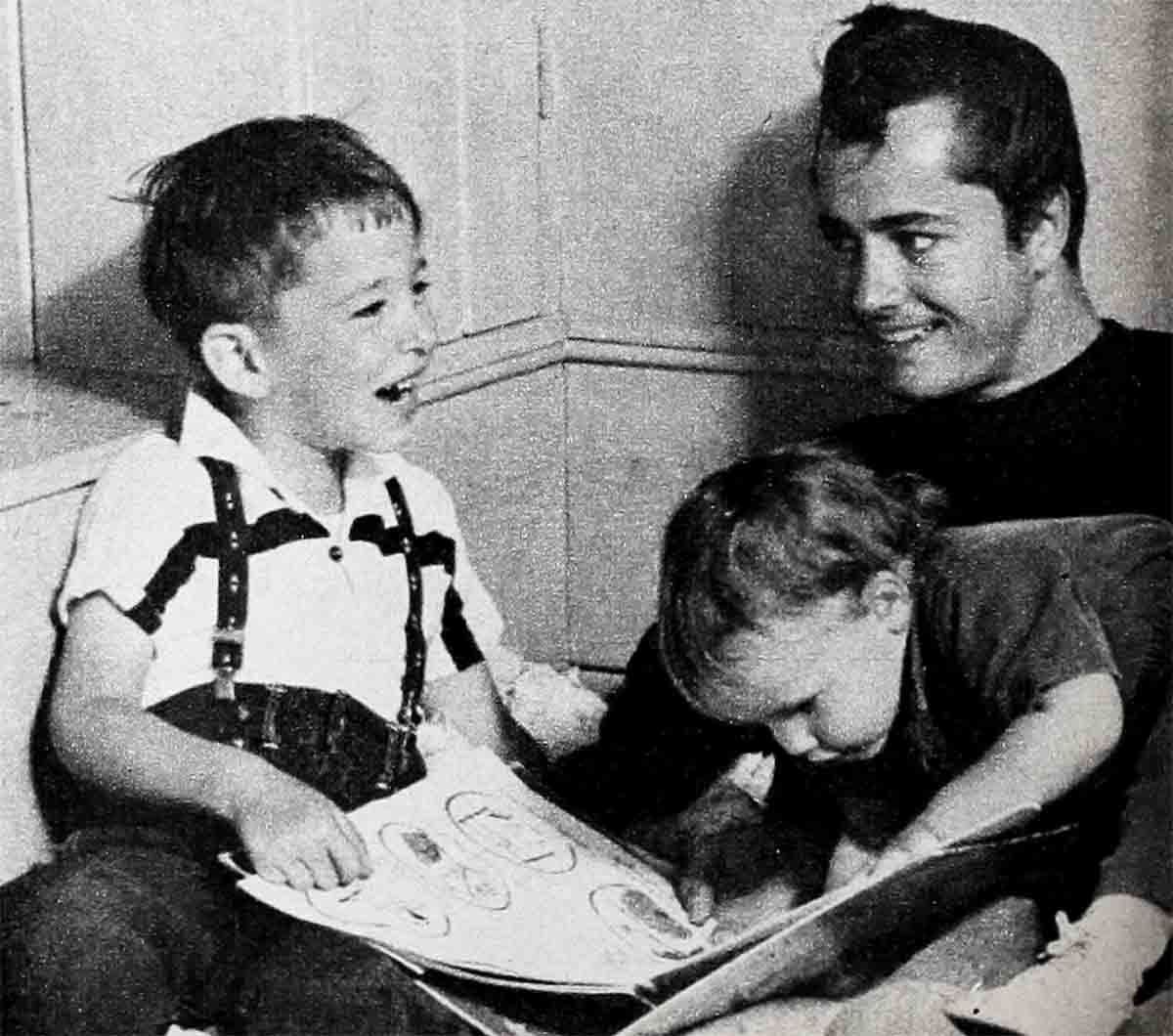

Tonight as this is written, John Derek is sitting in a small apartment on Sunset Boulevard trying to find the words to tell a five-year-old boy and two-year-old girl why their world is dividing and why Father isn’t coming home.

John went home to see both of his children, Russ, and his daughter, Sean, to tell them why he and Pati were no longer together. But the answers wouldn’t come.

“Daddy, you’re home,” Russ had said, running to meet him.

“Got any arguments?” said John, cuffing him playfully.

A little embarrassed, Russ said, “No—now we won’t get to sleep in the big bedroom with Mommy anymore.”

Russ had no arguments until his Dad started to leave again.

John had been gone for two weeks then. Any future for Pati and himself still looked pretty hopeless to him. He was convinced their marriage was at an end. He’d gone back to pick up a few clothes and to see his children and talk to them. But the words still would net come. And Russel, watching his Dad, kept at John’s heels. And questioned him.

“Why do you have to go, Daddy?”

“I have to go to work,” John said.

“I’ll go with you,” he offered eagerly. “No, you can’t go, lover. It’s a big studio and there are so many people working there—and . . .”

“But I wouldn’t be in the way, Daddy. Why would I be in the way?”

“Because I’ll be busy working in front of the cameras for Mr. DeMille.”

“I’ll work, too,” said Russ. “ I’ll work—I’ll tell Mr. DeMille I’m as big a ham as you.”

“I’ll don’t think Mr. DeMille would go for that. And you wouldn’t like it, lover, anyway. You’d have to sit very quiet.”

“I’ll be so quiet, Daddy.”

“But you’d have to be so quiet for so long, for days,” John went on, making conversation, and wondering how and where all this would end. Tough dialogue—fencing with words with this five-year-old—who was so much a part of him.

“I go where you go,” he said. “I’m not going to stay here. Why should I stay here if you don’t?”

“You’ll stay here with Mommy. I’ll be back in a few days. And I’ll take you riding,” John said.

Slowly John backed his car down the drive, eyes still on the little figure standing in the road. He blew him a kiss—and Russ turned his back on him. Then while John waited, Russ turned around.

“Bye, Daddy,” he said.

“I threw him a kiss and he turned his back—and I almost broke up,” John told Photoplay’s reporter later, the picture still vivid in his mind.

As he talked he was turning back the clock to twenty-four years before, trying to feel what five-year-old Derek Harris had felt. Trying to understand how Russ might feel.

“I’ve been sitting here in this stupid little apartment, wondering what to tell Russ. What can you tell him that he will understand? I don’t know how I felt at five now. I can’t remember. And I’ve been sitting here trying to think—to remember.

“I came from a divided home. I knocked around from pillar to post. I haven’t done too badly. And I don’t feel insecure. Certainly being exposed to our constant arguments couldn’t be healthy for him. That’s not a healthy atmosphere to raise any child in. Pati and I argued about everything—even how to raise him. And our tension and bickering was reacting on him. It got to where—whenever wed have an argument—Russ would start choosing sides and playing us against each other.

“No matter what happens Russ isn’t going to be without his father. I love those kids, and I’ve been more a father than many fathers of two. As Pati’s been more a mother—much more. We’ve been closer to them than many parents. We’ve been tested more.

“I left home—and that makes me the heavy. And that’s okay. But my heart’s in this thing, too. And I’ve got plenty of tears still inside of me—more than some people—because I’ve used them less.

“Unless we changed—and in seven years we haven’t—Pati and I just don’t belong under the same roof. It isn’t a healthy situation for anybody. And I believe we’ll all be a lot happier this way ultimately. If Pati fights me—and if this is going to drag on out for months and make Russ miserable—then I don’t know what will happen. We could get back together, although what would be achieved by this I don’t know. I don’t want to see either of the kids hurt. But, of course, Sean’s too young to know now.”

To Hollywood rumors that a third party had broken them up John said decisively, “This just isn’t true. And it isn’t fair either, involving other people in our troubles. I didn’t leave home because of another girl, and I’m not staying away now because of another girl. When Pati says ‘Somebody’s trying to break up our marriage,’ she’s right. But that somebody is Pati Derek—and that somebody’s John Derek—and between us we’ve done a pretty thorough job of destroying our home.”

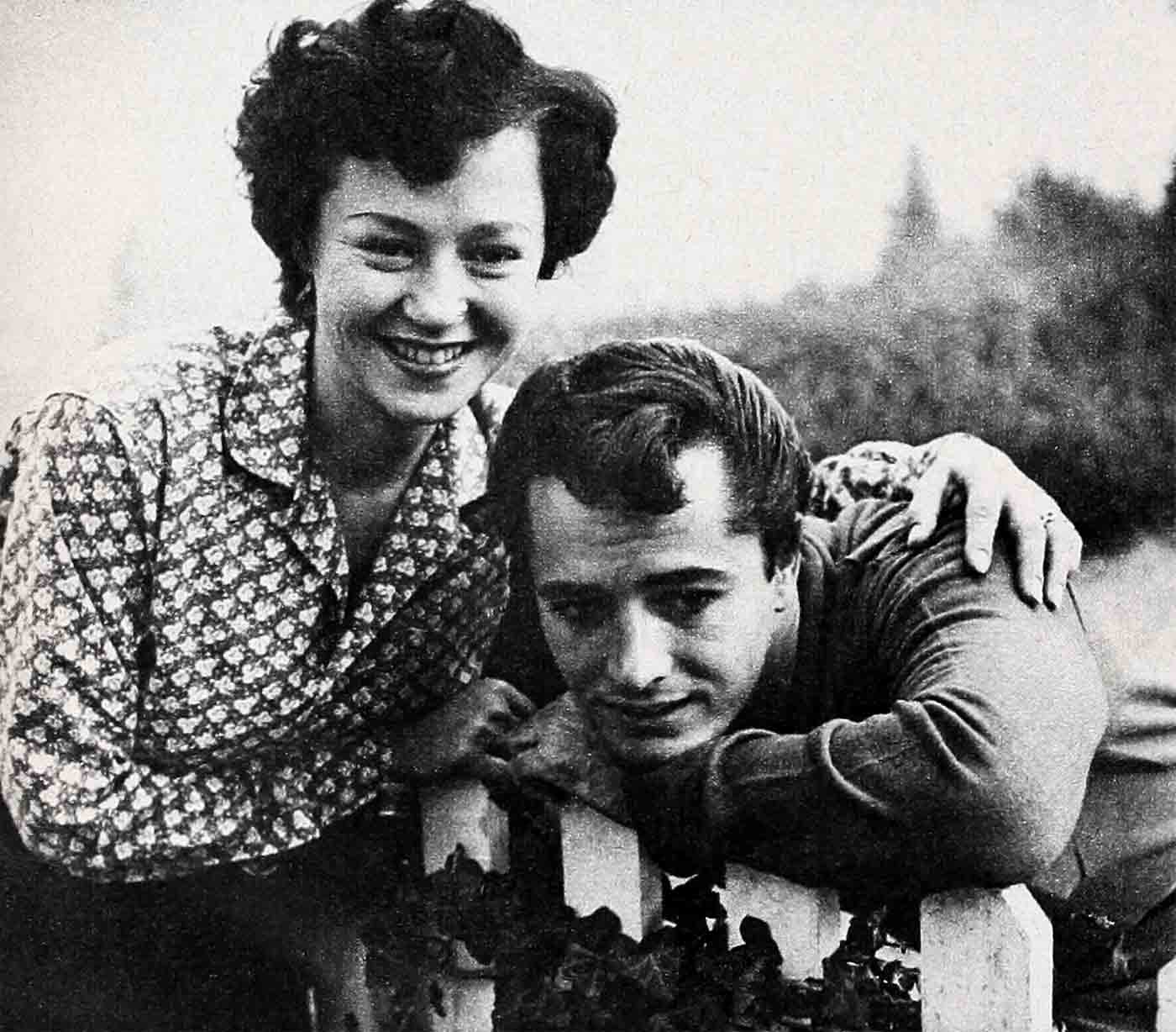

John filed for divorce, charging mental cruelty. As he talked, legal wheels were in motion writing what seemed to be the beginning of the end for the pretty dark-eyed French actress, Pati Behrs, and the handsome young actor and ex-paratrooper, who were married in Las Vegas when they both were just beginning their movieland careers seven years ago. They’ve been Hollywood’s stormiest love story, two vivid spirited people who’ve fought and loved with equal enthusiasm.

As for the fundamental causes of their incompatibility, John says, “I just don’t know. All I know is that after seven years together—I’m not there. It’s not a game. I’m not playing a part in a picture. And I didn’t leave for another girl. I don’t know what’s wrong with us basically. I’ve never told Pati—but I even went to a marriage counselor. But when you come right down to it—your problems are your problems and the answers have to come from you. Distrust and too much discord—constant discord—can be difficult to overcome. And let’s face it, I’m not too great to live around. I’m selfish and I have a very bad temper. I’m impulsive and when I want to do something—when I want something—I want it now.

“I want Pati to have separate maintenance,” John said. “And she’ll get more money that way. I want her to have the house, the Cadillac, all the money we can manage. I just want to get it all squared away, get the visitation rights settled and be able to see our kids in a good atmosphere. I miss our kids.

“Pati’s a wonderful mother, and she can be a living doll when she wants to be. She’s a very attractive woman, too. We’ve been very close—closer than many—because of our little boy. If we were to go back together ever, we could be on our best behavior for a while and everything could be fine. But that would just be a crutch. The basic difficulties, the arguments would still be there. And if we broke up again, it would be even worse for all concerned. The older Russ is, the harder it would be for him.”

To friends of both, their separation has often seemed an eventuality. Theirs has been the constant friction that could weaken and wear away the strongest tie.

There’s the clash of John’s impulsive way of living and his artistry—versus Pati’s more cautious practicality. John’s fever for perfection—and Pati’s feeling of rejection.

Ironically enough, this was to be their year to straighten out their differences. To have the time and freedom to make their marriage work. “It will be easier,” John said, “when Russ is in school—when Pati isn’t confined so much.”

But life wouldn’t wait, so now they fight with the same gusto they’d loved.

An alternately angry and tearful Pati is convinced there’s a third person seriously involved in their difficulty, although she admits, “John is not a girl chaser.”

“I’m not a girl chaser?” says John in turn. “Then why did she always tell me I was? Why was she always so jealous?”

“John says he isn’t happy and I’m the reason. I’ve told him he has to give happiness to get happiness. All John can say is, ‘We don’t get along.’ That we fight, fight, fight. Sure we fight. He doesn’t realize he provoked them. I’m willing to get along, but he has to help me a little. And that’s not enough after seven years anyway.”

When it comes to provoking arguments, Pati’s right. He doesn’t realize it—nor would he agree with it. “I want Pati to fight for her convictions. When she really believes something. But not just for the sake of argument. I don’t like to argue with her anyway. She’s too clever for me. By the time we’re through, I’m always wrong, and the law of averages won’t allow anybody to be that wrong. Pati will argue when she doesn’t even know what the subject is—until I finally say something that gives it away.”

They’ve always had their own definitions of extravagance.

“He bought a swimming pool—and a hi-fidelity—and I didn’t think that’s right when we haven’t finished furnishing our house. We still have no curtains in the bedroom—and the doctor bill for the children’s shots still not paid.”

“Ask Pati what she spends on shoes. How many pairs she has. And that French imported coffee—we could do without that —ask what she spends on ‘just Pati’ and what I spend on ‘just John’—I like to have things everybody can enjoy.

“It wouldn’t make any difference how many nurses we had—Pati’s always done their job for them,” John suddenly said. “We’ve never fired any of the help—we didn’t have a chance. They all quit.” He admits he’s allergic to making plans. He likes to move on impulse. For him, planning, scheduling take all the adventure out of the whole thing.

In Pati’s opinion, “I understand you shouldn’t neglect your husband for your children, but you shouldn’t neglect your children for a husband who doesn’t know what he wants.”

John, on the other hand, believes he’s definite about what he wants. “I want to live. Not just exist. Not just talk about living. I like hobbies, too. Pati won’t participate, won’t share the fun with me.”

“I like to read and watch television. I’m not taking up ceramics or something with him. Anything John takes up—he’s sensational. But by the time I start getting interested, John’s mastered it already and ready to go on to something else.”

On Pati’s birthday, John thought he had a great idea. “I’m going to take her to Apple Valley for swimming and for lunch.”

“But I don’t feel like going to Apple Valley, I’d rather go to some nice place to dinner here.”

“I want to do something for you, and you don’t want to go.”

“You don’t want to go to Apple Valley for me, you want to go for a drive—and get a tan.”

They wound up going to a movie and having hamburgers in a drive-in. John said, “Pati can’t do the physical things I live for. Horses are my life. I love them, but on the other hand, Pati loves to dance—and I don’t like it. I do it badly, and I’ve made no effort to try.

“Pati’s been under a great strain since Russ was born,” John says now—and he’s said it before. “She’s nervous, and who wouldn’t be, living for five and a half years within four walls, sticking so close, never once overnight away from the children—that’s too much. When Russ was sick, that was the thing to do. That was different. But he hasn’t been sick for a year now—and it hasn’t changed.”

About the filing of the divorce suit, John says honestly now, “I don’t know why Pati would be shocked about this, we’ve talked about it too many times. She shouldn’t be. Only in the way I left—but I have no guts when she starts to cry. It was the only way I could ever have gone.”

Three months before this, they’d reached an impasse. Pati had suggested John go away for a little while and John had gone.

He was gone one night. “The next night I went out to see my kids and pick up some clothes. I didn’t go to stay, but Pati was so nice—I stayed.” She was away from home when John got there, playing Scrabble with some friends. When she got home and found him there, she was starry-eyed. “It’s so wonderful to have you home,” she said. And he stayed.

“I couldn’t tell her.”

Some weeks later, convinced they were just prolonging a hopeless situation, John thought he might just see an attorney and find out what the legal approach would be. While he was there, a middle-aged man walked in. He looked beaten and unhappy. He wanted a divorce, he said. “When did you first decide to get a divorce?” the lawyer asked. “Twenty-two years ago,” he said.

Twenty-two years. John thought of the years the man and his wife have lost. “Go ahead and send the letter,” he told the lawyer.

On Saturday morning, he left the redwood ranch house in Encino with its freeform swimming pool and all the dreams they’d had for it. “It could be a beautiful place—I had a lot of plans,” John says now.

As he left, Pati felt intuitively he might not be coming back. “I wouldn’t be surprised if I were served with papers,’ she said to him. John was stopped. As he says now, “I had no answer.”

“I’m not kidding you,” said Pati.

“You shouldn’t be,” he said.

When he got to the door, he looked back.

“John—”

“What is it?”

“Oh—never mind,” Pati said.

As John says slowly now, “I looked at her and I almost went back, but if I had I’d never have had the guts to go again and I knew we couldn’t go on that way.” But with two like John and Pati Derek, it takes more than a piece of paper, however legal, to close the door. And the strength of their emotions may open it.

“We’ve just been through too much together,” Pati says. “It would be easier to go home,” says John, “than staying here in this lonely apartment. But I think we’ll both be happier when we get this all squared away. Between us, we have brought two more people here on this earth, and we’re responsible for them. We must do what’s fair and what’s best for them.

“I’m not going to tell Russ until I know what we’re going to do. Whether it will be divorce or separate maintenance or what.”

The challenge of still trying to make their marriage work could send Pati and John back together, or a little five-year-old boy could lead them back.

When he gets home from school now, he whirls his red bike back and forth on the patio.

“Daddy has to help me on the big bike, but I can sure ride this little beauty,” he says pedaling away. “I’ll be glad when I can switch from the school bus to my bike and ride it to school.”

But when the sun goes down, his make-believe world stops, and a little five-year-old boy watches tirelessly through the window for the lights of a car and listens eagerly for every ring of the phone, wondering when his daddy is coming home. And beyond the valley on the other side of the hills, his father, John Derek, sits in a room and follows every move he makes from memory.

THE END

—BY DIANE SCOTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1955

No Comments