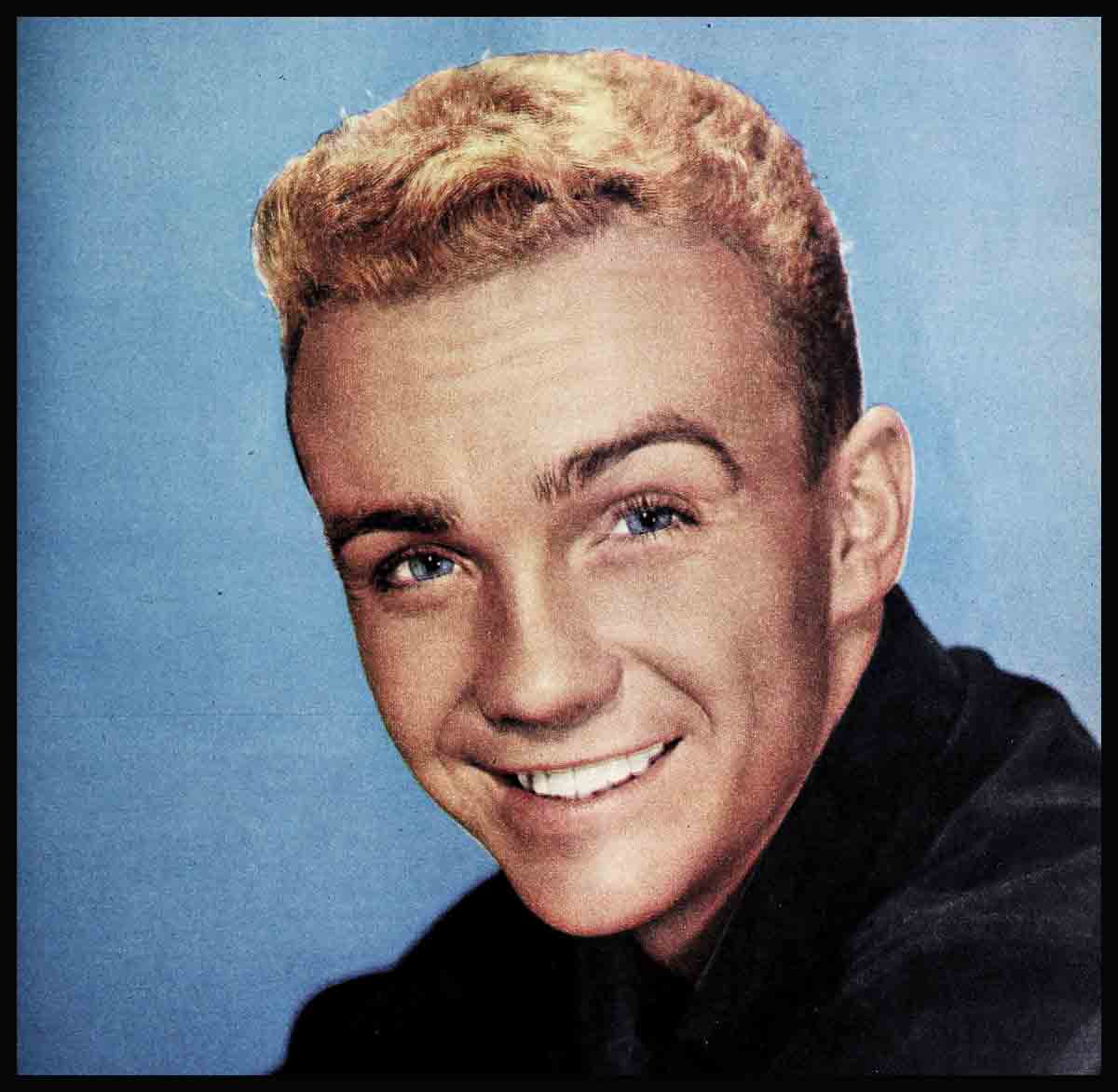

Ben Cooper’s 21 And Terrific

“I can’t date a girl younger than I,” groans handsome Ben Cooper. “We have nothing in common. I date older girls. I hear the oe wee old ‘mother-complex bit.’ What do I do? I’ve already got a wonderful mother. I don’t want another. I just want a girl I can be mentally emotionally and physically attuned to. So I look like a kid and olde girls feel awkward going out with me. Let me put it this way. I am available; I’m wide open to love and romance. I’m one hundred and fifty pounds of willingness.”

Ben’s problem of looking younger than he is, yet having the maturity of a guy much older, is a problem this talented, rising young actor has been fighting since he was eight. He’s always looked young, acted older!

First of all, at twenty-one, Ben’s already a veteran of thirteen year in professional acting. “Since I was eight,” he explains, “I’ve had to give the same quality of work—and receive the same pay base—as men two or three times my age. Because I had to mature faster, I was treated as an equal in the theatre; at home Mother and Dad treated me the same way. If I planned a weekend and a show came up, they left the decision up to me. I had to use my own judgment. Of course,” Ben grinned, “I usually chose to do the show.”

Child stars grow up in one of two ways. Either they gather their little false world around them and refuse to grow out of it when they reach the teens or they have the basic stability and intelligence to grow faster, learn much and mature beyond their age.

When, at eight, Ben gained the part of Harlan, the youngest Day boy, in New York’s “Life with Father,” the pattern of his life was necessarily changed. But with the supervision of his practical and loving parents, he was taught to make his own decisions as soon as possible, to look upon acting in the right light and to take his normal place with the fellows he played with. As a result, Ben never once went through the harrowing experience of being ragged about his acting by his schoolmates. His allowance of fifty cents was the same as theirs, he played the same kind of ball; enjoyed all their normal pleasures and indignations and shared his horse, Gypsy, with them.

Even at eight he showed the outgoing interest and deep perception that was to become so much a part of his personality. On his fifth night in the Broadway production, the prop man forgot to leave the catechisms on-stage. In an ad lib, Howard Lindsay as Father Day, asked Whitney to bring them. Then he turned to Ben playing Harlan and started to ad lib through the wait. “What,” he asked, “would you like me to read you?” He could have cut out his tongue the minute he said it. What indeed does an eight-year-old boy want to read? Comics, of course. Young Harlan looked at his stage father and ad-libbed, ‘Gulliver’s Travels,’ I think.” On that night, Howard and Dorothy Stickney Lindsay proclaimed Ben a ‘pro.’

Later in the run, another actor took Lindsay’s place as Father Day for the summer. In the third act, while the family was seated around the breakfast table, the actor suddenly went blank. Ben was the first to see it. In a low tone, with his head down in his cereal, he cued the actor. The man picked up the line and remained blank. For the duration of the third act, young Harlan was unusually close to Father Day. He was giving the actor his part—line at a time. When the curtain rang down, the actor publicly, in front of the rest of the cast, thanked Ben. Age—smage—an actor had come to the rescue of another actor. Ben was indeed a pro.

At home, too, he was exhibiting the same instinctive good judgment and understanding. One night when Ben and his mother were having their usual after-theatre snack, she sent him up to bed while she cleaned up the kitchen. As Ben started up the stairs, he saw a hugh shadow on the stair well. Looking up he saw his older sister, Bunny, leaning dangerously far over the top banister on the second floor. In an unearthly voice, she said, “Don’t be afraid, Benny, it’s only me.” Ben realized she was walking in her sleep and ready to topple over the rail. Slowly and quietly he started walking up the stairs talking softly. He reached her, pulled her back to safety and led her back to bed. The next morning she didn’t remember it at all. But his ability to master any situation without childish fear was proven.

It was the same when he and Danny, his best friend, went paddling out in the Long Island Sound in a kayak. As they lived two houses away from the Sound, Ben was on friendly terms with the ways of water. But both boys missed seeing a large ship coming until too late. The heavy waves from the ship’s backwash turned the kayak over. Danny came up choking and sputtering. Ben swam to him and became wound up in a death grip. Slowly and easily he worked with Danny and finally, through his own lack of fear, eased the death grip. Then he pulled Danny and the kayak back to shore.

By this time he had grown, literally, into the role of Whitney, the second youngest son. During that period, he discovered the medium of radio. Or, rather, it discovered him. For inside a year, he was playing five running parts in daytime dramatic series and playing in top shows with top stars. He was working so much in radio that he finally made the decision to quit the cast of “Life with Father.” By the time Hollywood beckoned, Ben had worked in thirty-three serials and thirty-two hundred radio shows.

At fourteen Ben had developed a social conscience that would put a lot of grown men to shame. At the height of his radio career, he was asked to go on tour with Bob Feller to combat juvenile delinquency. The Joe Lowe Corporation was a Popsicle company. They made their money from kids, but they wanted to do something for the kids in return. So they asked Ben to lose his own identity and become Popsicle Pete. Because Bob Feller was a sports hero and not inclined to speechmaking, Ben became his personal representative in the field. They gave mails awards to kids who had done an outstanding service to the community. It could be saving a life or organizing a better Boys Town. Whatever the reason, the kid received a $100 war bond and a gold medal. Ben and Bob went before club after club—Kiwanis, Rotary, all of them—to tell of what they were trying to do. In these meetings, Ben learned to speak easily for five or thirty minutes, according to the need. He learned to ad lib and, because he believed so completely in the project, there are thousands of men

ay who remember that earnest Popsicle Pete selling the good in kids.

It was inevitable that a day would come when Ben sat at the speakers’ table of National Father’s Day. Bob Feller had been proclaimed Sports Father of the Year. After a brief thank you, Bob turned the talking over to his side-kick and personal representative, young Ben. Bernard Baruch, Dwight Eisenhower, Drew Pearson and Jo Stafford shared the speechmaking with a fourteen-year-old Popsicle Pete that day.

In 1947 television reared its infant commercial head and Ben got in focus. He was as successful in Tv as he continued to be in radio. During his teens he managed to do between two hundred and two hundred fifty shows, mostly leading parts, starring in some. His talent put him in shows like “Suspense,” “Kraft Television Theatre,” “Armstrong Circle Theatre” and “Fireside Theatre.” The top-caliber shows were using only top-caliber actors; they could depend on Ben.

During this period he completed his studies at St. Luke’s School and Lodge High School in New York and entered Columbia University at sixteen. “It was rough at first,” Ben remembered. “I was with veterans and older students. They looked at me as if I were in diapers. It usually took about two sessions in a good class before they could accept me as one of them.” Majoring in dramatic art during his two years at Columbia, Ben studied directing as well as acting. One of his instructors was Gertrude Lawrence.

His home life, too, was rich and rewarding. The Cooper home was always open to friends and more than half of the parties and dinners were at Ben’s home. “Ever since I was young, younger, that is,” Ben corrected hurriedly, “a wonderful home open to friends has been part of my life. I could always call and ask to bring two more home for dinner and always get a

happy okay.” Between Ben’s high school gang and college friends and his acting friends, the Cooper abode was happily and noisily occupied at all times—except Monday nights.

Monday nights Ben was with the troupe that went to a veterans’ hospital. His social conscience and desire to reach out to others led him to entertain in that hospital and learn very much, very young. There he saw strong men weak and weak men become strong. He experienced in every way indirectly the aftermath of war. The mental wards were the most heartbreaking. The men there took care of each other. “One fellow couldn’t remember to put his cigarette out. If he weren’t watched, he would let it burn right through his fingers. These fellows wouldn’t even interrupt a conversation to take his cigarette away. They just reached over at the right time and snuffed it.” Ben sat with his memories for a minute, “Some of those Monday nights, I’d be so tired I’d hate to make the effort. But the minute I was inside that hospital I knew it was worth it. We’d all go out refreshed.

“Have you ever seen a bunch of actors not be able to say a word? It happened one night. One fellow in the mental ward hadn’t spoken a word since he’d been there. We made a habit of conducting a talent show of the fellows on a tape recorder and playing it back later for them. Week after week the fellows sang, danced, read scripts and announced—all but one man who sat quietly alone. Then one night he suddenly jumped up, grabbed the mike and started singing “On the Sunny Side of the Street.” He put his whole body and soul into singing that song. He was good, too. When he finished the ward broke into wild applause. They knew how much more than singing had been done. When we played it back, we were running out of time, so the fellows suggested we speed it up so we could hear him sing again. At the end of his recorded song, the gang joined in their own applause again, and the fellow sat there with tears streaming down his face. He wasn’t alone. When we packed up and started down in the elevator together, no one said a word. How do you talk around a giant-sized lump in your throat?”

In 1952, the year Ben became nineteen, he was asked to serve as a delegate to the AFRA (American Federation of Radio Artists) convention. He accepted the nomination. He decided to join the anti-Communist campaign group. He took his stand with, “If a burglar breaks into your home, are you for burglar alarms and a well-manned police force? Naturally. But at that moment you must also be against the burglar. I am against Communism.” Ben was elected and served on the committee that handled contracts with the studios. AFRA had served him well and fairly over the years of his acting and he, in turn, felt the responsibility of serving AFRA. That he served well was proved the next year when, on a visit to New York from Hollywood, he was reelected and worked with the newly merged television and radio union, AFTRA.

“For years I prayed for a chance to act in pictures. I wanted to come to Hollywood in the worst way and,” grinned Ben, “that’s the way I would have come—the worst way. When I did get the bid, I was ready. With even my years of professional experience, my first try failed. I came out to test for Warners’ ‘Retreat, Hell!’ When Russ Tamblyn got the part, I went right back to New York and television.”

But Herbert Yates, Republic’s president, saw the test of the New York cowboy galloping across the screen and decided to put him in his own stable. Fortunately, Ben’s love of his pony, Gypsy, and his constant riding as a boy made him a “cowboy.”

It was as Turkey, the youngster who was lynched in “Johnny Guitar,” that the public discovered Ben. Photoplay and the studio were flooded with questions about him. A studio can only hope they have a star on their hands. The public makes the final decision. On Ben Cooper there was no hesitation, they decided. Ben’s gamble in abandoning a successful career in New York for a chance in movies paid off.

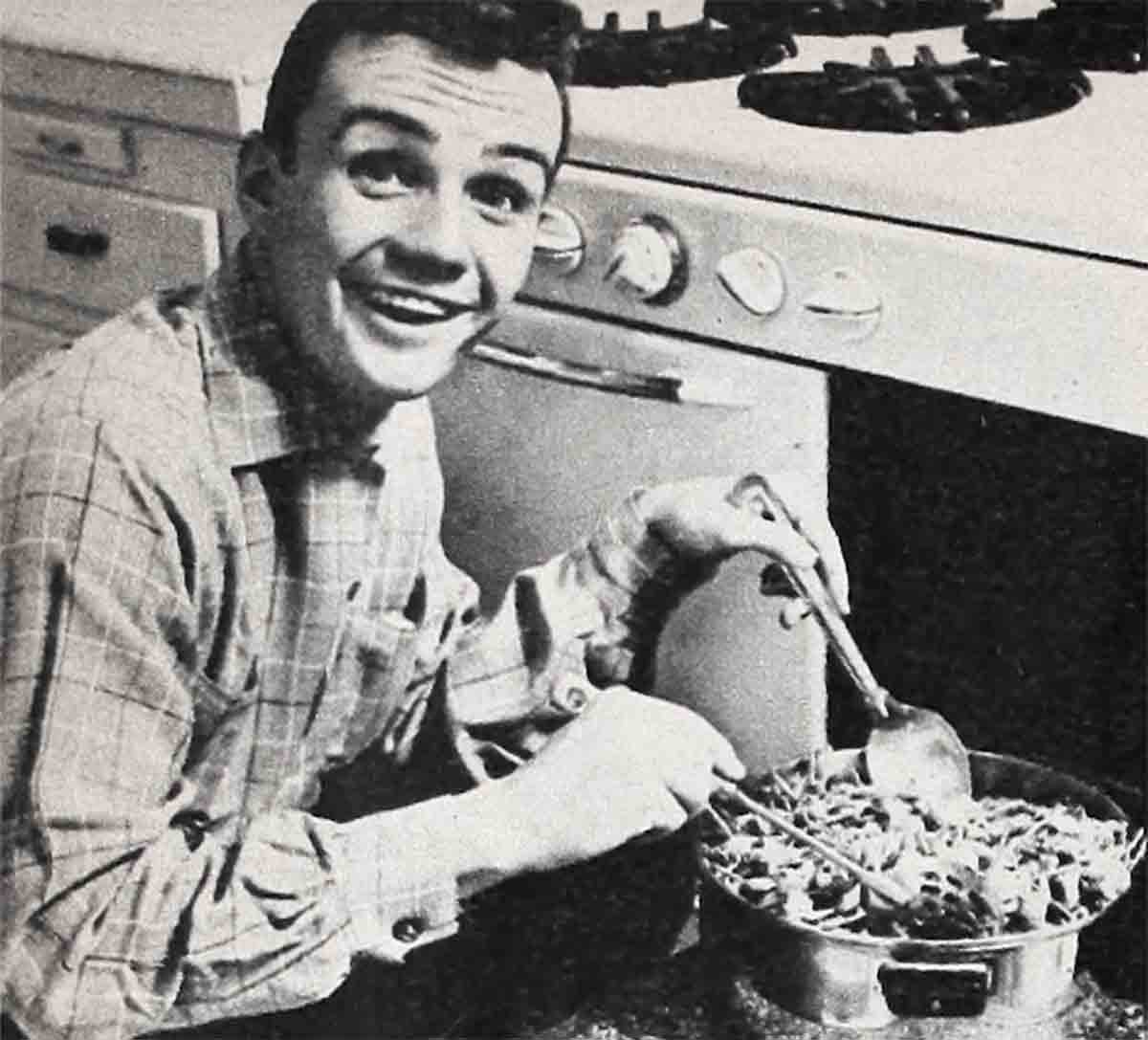

So Ben settled down to living in and loving Hollywood. With his instinctive ability to make friends, he soon had a comfortable and congenial group using his apartment across the street from Republic with the Open Door Policy. Ben’s an excellent cook. Be it two or ten for dinner, he can whip up a barbecued chicken with a special candy-coating sauce, chocolate cake and a chocolate sponge pie (“not ready-mix,” he says proudly). After his guests are lulled into lethargy from very full stomachs, Ben will pull out his guitar and sing folk songs.

One night at Sterling Hayden’s they were celebrating the finish of their picture, “The Last Command.” Suddenly Sterling asked Ben to go home and get his guitar. After Ben left, Sterling said, “I’ve heard a lot of guys sing folk songs, but Ben’s terrific. He should do his own show on television and make a mint.” Ben returned with the guitar and proved Sterling right.

During the filming of “Johnny Guitar,” Ben won an ardent fan and fast friend. Joan Crawford thinks the sun rises and sets in Ben Cooper. “He’s the dearest, kindest, most understanding man in boy’s clothing I’ve ever met. My son, Chris, actually follows him around like a puppy in pure hero worship. Ben has spent many Sundays going to visit Chris at school with me. One Sunday he asked if he might give Chris a cowboy shirt he had loved as a boy. It was a beautiful shirt. When he gave it to Chris, Chris was so thrilled, he almost cried.

“I’ll never forget his kindness on the ‘Johnny Guitar’ location,” Joan said warmly. “I had Chris with me for a week. It happened to be the time of his birthday, so I had a cake flown up for a party. It was big enough for a hundred. I knew Ben had planned to go to another party that night, so when Chris stubbornly refused to cut the cake until Ben came, I was frantic. Then the door opened and there stood Ben, slicked up and ready. ‘See,’ said Chris, and promptly cut a piece of cake big enough for ten people and handed it with adoring eyes to Ben. Ben graciously gorged himself.

“After Chris went back to school Ben found out he wasn’t writing me. So he wrote him a beautiful letter saying that when he was a little boy he hadn’t written his mother as much as he should, but he knew Chris was better than he about things like that. It worked, too. Chris started writing.

“Along with being a wonderful human being,” Joan said firmly, “Ben is the finest actor for his age of anyone I’ve ever met. His talent and sensitivity can’t be held down. I think his home life with his terrific Mother and Dad and his divinely mad sister, Bunny, has created one of the finest representatives Hollywood is going to have in a long time to come.”

Bunny, Ben’s beautiful sister, has the same zest for living and lively sense of humor that Ben is endowed with. Both claim they get it from their parents. On her first trip out to visit Ben, Bunny (a New York model) decided to diet while here. “Of course, Ben met me at the airport with a report of the chocolate sponge pie (Mother’s recipe) waiting for me at his place. He spoiled me horribly and I didn’t lose an ounce.” Since that first visit, Bunny has been spotted by the talent scouts and is waiting to hear about a contract at a major studio.

When Bunny decided to share Ben’s apartment, the Cooper sense of humor created havoc with Ben’s date life. Bunny would answer the phone sweetly and coyly. When it was a girl on the other end of the line, silence and confusion reigned. “Ben isn’t here,” his loving sister would say, “may I take a message?” After getting all the reaction she could from the uncomfortable girl, she would then explain that she was Ben’s sister.

When Ben plays, he plays hard; and when he works, he works hard. When he won the coveted role of Sailor Jack in Paramount’s “Rose Tattoo” over two hundred other actors, he settled into the job of earning his co-star billing with Anna Magnani, Burt Lancaster and Marisa Pavan. His impassioned scenes with Marisa will plant him firmly in the eyes of the public as a star. Thirteen years of experience went into his portrayal. One girl, lucky enough to see his screen test for the role, said, “It gave me goose pimples. He’s for real.”

Together with his youthful exuberance and vitality, Ben has the joy of living of the very young, and yet, can be father-confessor, brother, arbitrator at the drop of your mood. His maturity and wisdom have abruptly stopped many from starting to pat the head of the happy youngster he looks. He stands firm for the things he believes in and has strong moral integrity. Richard Carlson is already trying to get him on the board of the Screen Actors Guild. He knows that a youthful outlook in a mature mind, plus a deep sense of responsibility, will be an asset to SAG. And if Ben does join the board, he will give his whole heart to it as he does everything.

The boy who started life in Hartford, Connecticut, and spent his childhood on the Long Island Sound and the stages and studios of New York is fully aware of the contradictory parts of his nature.

“I have three questions always uppermost: Where are you going? Where do you want to go? How are you going to get there? I try to keep the answers to those questions straight and unconfused at all times. I realize that I am in the process of my basic attack of moulding my life. I’m forming patterns I want to retain. I want to live up to everything that’s in me for myself and my family.”

There’s no doubt, at twenty-one, Ben Cooper talks and thinks like a man of thirty-five. There’s also no doubt by those who know him, at thirty-five, he will not only be one of our finest actors, he will be a man the industry will be proud of.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1955