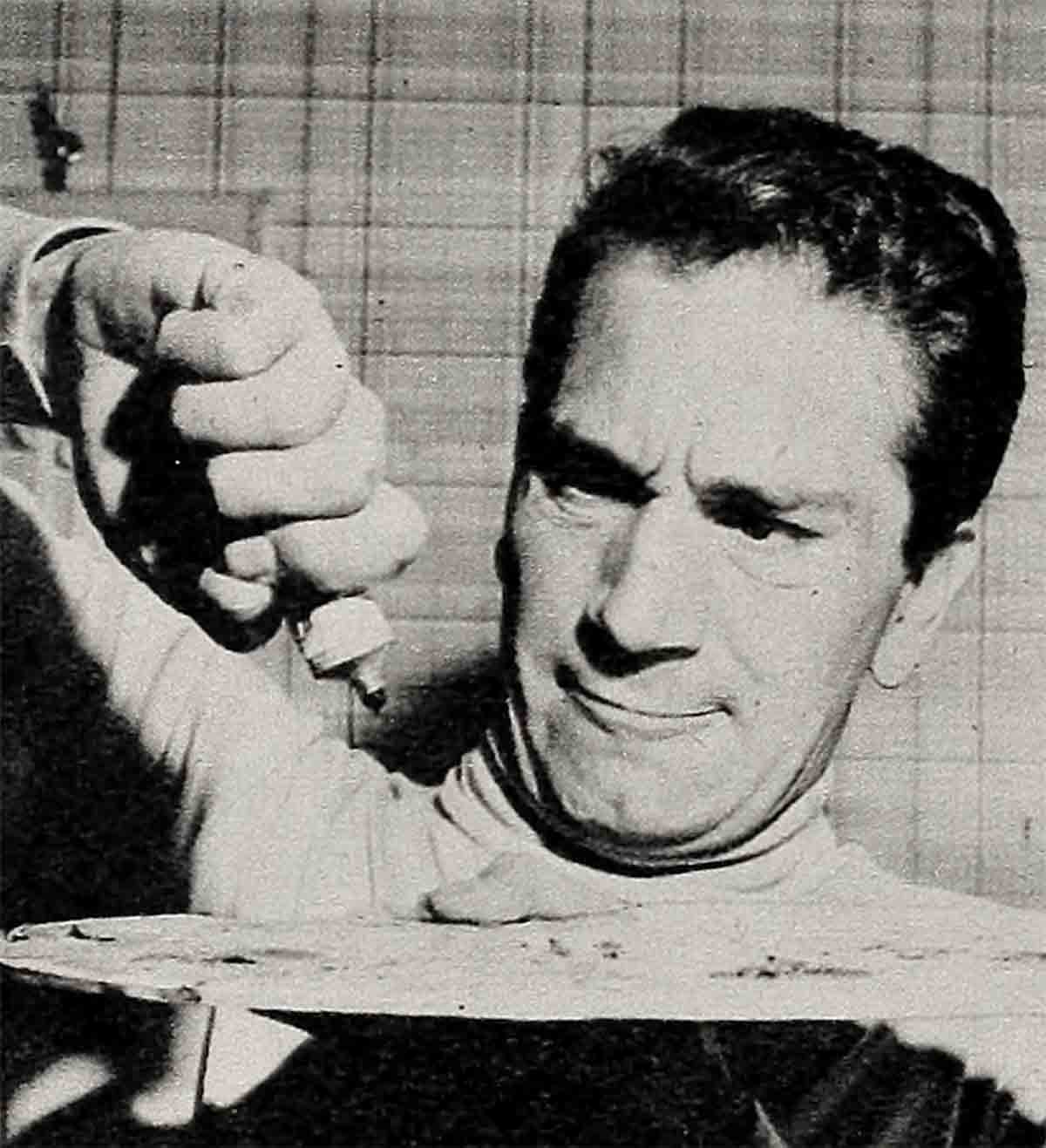

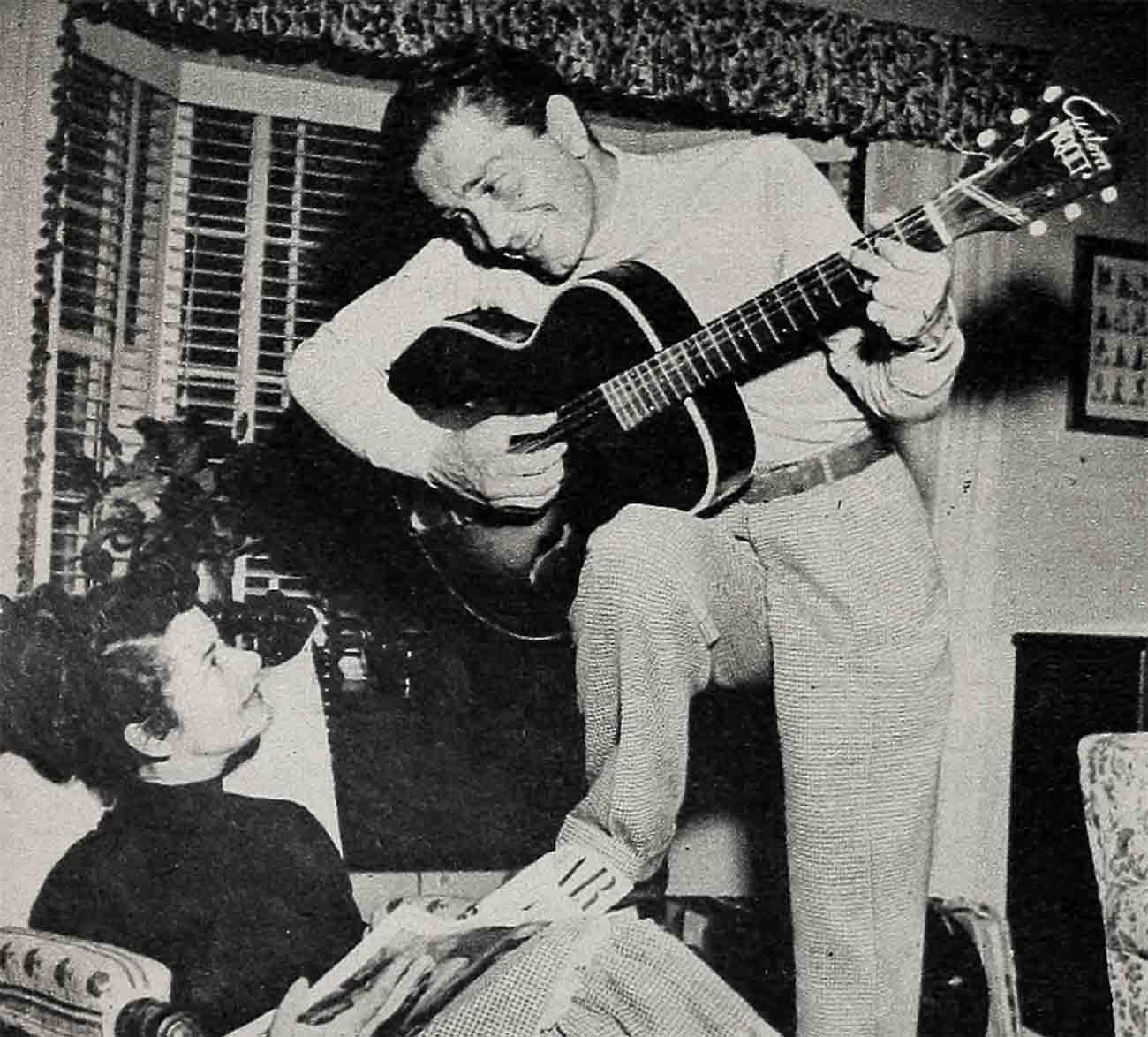

“Easy Street”—Richard Conte & Ruth Storey

Values are easy, for some people. Take Richard Conte. He lives on a hill, in Hollywood, and. his wife has a mink coat, and a maid stands around being helpful, but he got his the hard way, and none of it fools him a bit.

You know what’s real, and you know what isn’t, and you can enjoy them both. It would be silly to say Conte doesn’t. But the balance is there.

Go back to New York, and the stage. Off-months, he’d work in his father’s barbershop. Go back still further, to his childhood. A Jersey City slum.

His father, Patsy Conte, got off the boat from Italy, and came to Jersey City. There wasn’t any reason. He could have ended up in Kansas if he’d had the fare.

He opened a barber shop. Haircut 35c, shave 15c. (During the depression, the combination went for a quarter.)

Richard was born in a tenement. It was right on the Hudson River, in a neighborhood of factories and freight yards. “It wasn’t nice, but it was interesting,” he says now. “It was the kind of background that sets you up well for whatever happens later.”

Times were bad. You can remember how bad times were. There weren’t any clothes, there wasn’t much rent. Some months, the Contes would have to face the landlord. “We haven’t got the money.”

And the landlord would shrug. “Never mind. Another month. Things will get better—”

Sundays, Richard got his nickel allowance. If he was feeling low, he’d rush right out and get an ice-cream cone.

Other Sundays, he’d wait, holding the money carefully, until the Nickelette opened. The Nickelette had 200 seats; it had Tom Mix; it was food for the soul.

There was the usual gang of boys in the district. They’d swim in dirty Hudson water, sneak into freight cars.

At home, life was good. Somehow, you ate. And there was always music in the house. Nicky’s father had played with street bands in Italy; there wasn’t an instrument he couldn’t handle.

He tried to pass his gift on to Nicky. They spent hours together, the man pulling the boy’s ear and crying, “No, no, no!” He never pulled the ear hard enough to hurt it any, and Nicky knew about solfeggio, when long division was still a mystery to him.

After Nicky got to high school, he’d help out in the shop, Saturdays. He’s proud of a faded old picture he has. It’s the inside of the shop, and three barbers behind three chairs. Nicky’s chair was second.

High school being over, eventually, Nicky took stock.

Four years later, he was still taking stock. He’d driven a truck, played piano in a summer hotel orchestra, been a Wail Street runner, a stock boy, a floorwalker. He was no nearer his first million, and he didn’t particularly mind. What he did mind was that he hadn’t yet hit anything which satisfied him emotionally.

He was reflecting on this, as he tried to shove a pair of small shoes on the large feet of an insistent lady. If you were a shoe salesman, and he was, you were not permitted to say, “Madam, go away, I beg of you.”

Eventually, she went away, anyhow, and he wiped his forehead, and greeted a friend named Peter Leeds, who had just come in.

Leeds had a brilliant idea. “Why’n’t we get jobs as waiters in a summer hotel?” he said. “In the Catskills.”

The Catskills sounded green, and cool. The city streets were grey, and the heat blinding. “Sure,” said Nicky happily.

In the Catskills, it was pleasant. Only the waiters were expected to pitch in and stage-act too. This, Nicky hadn’t been told. It was a place with entertainment for the paying guests, and the first thing he knew, Nicky was playing Vanzetti, in a play about Sacco and Vanzetti, the martyred Italian labor leaders.

Politically, he- was ignorant; but the speech he’d been given stirred him. He read his lines so well that three members of the Group Theater (the famous cooperative group) approached him after the performance.

“We’d like you to join our acting classes.”

“Thanks,” he said. “But I’ve got no time for acting. I have to earn a living. When I’m not serving in the dining-room, I’m cutting hair in the barn.”

They invited him to come to the rehearsal of a play they were doing, in any case, and the next Wednesday night, he went.

It was Clifford Odets’ Waiting For Lefty; he sat there spellbound, and shaken. He’d never seen a play before; and such a play.

When the final curtain came down, he tore backstage and accepted their offer.

His three discoverers were John Garfield, and the two directors, Sanford Meisner and Elia Kazan.

By the end of the summer, he could think of nothing but acting. “Up until that time,” he says, “I’d been a limited Italian boy, aimless, looking. for something—”

In the fall, he got a scholarship to the Neighborhood Playhouse free, and he got $15 a The course was for two years, and on. The course was for two years, and he lived at home, and cut hair on week-ends.

In the summer, he got odd stock jobs.

When he graduated from the Playhouse, he was scared. No more 15 bucks. No more security. But there was a job for him in Saroyan’s My Hearts in the Highlands (it ran six weeks), and then a gangster part in the road company of Golden Boy.

After that came his first Hollywood try. He made a movie called Heaven With a Barbed Wire Fence, then turned around and went back to New York.

“I’m not ready,” he explained, more to himself than to anyone else. “I need experience.”

So it was Broadway again. Four weeks in Heavenly Express. Two weeks in Odets’ Night Music, and he was earning Equity minimum. Forty bucks a week, and half pay for rehearsal. It wasn’t a living.

But he was in love, and it kept him going. He’d met this girl, this Ruth Strohm in Hollywood, at John Garfield’s house.

She was an actress, and now she was back in New York, too, and when either one of them had money, they shared it.

empty pockets, full hearts . . .

Ruth had a mother, a singer, who was generous about meals; Nicky had a cousin, a Bostonian, who handed on his old clothes.

They’d walk around the streets at night, and call it having a date. It didn’t much matter what you called it, it was wonderful.

She loved him because she could see through him. That his intensity, the brashness, was a natural response to a hard world, that he was hiding an oversensitive spirit, lyric and poetic.

He loved her less analytically, because she was small and pretty and red-headed, and bright, and she made him feel good.

They saw the last two acts of a lot of Broadway plays. It’s an old trick. You stand around and mix with the people who come out for a cigarette during the first act intermission. Then the bell rings, and you march into the theater with the rest.

The only times it wouldn’t work were when shows were sold out. Those days, practically nothing was sold out.

In 1941, Nicky got a lead. Walk Into My Parlor, it was. George Abbott saw him, and handed him the starring part in Jason; Jason won him the Critics’ Circle award. It all led up to a year in the army.

He walked into Ruth’s place eventually, a medical discharge in one hand, and nothing in the other. “I’m free,” he said, and she said, “So you are,” and he got a job in a play called The Family. It didn’t last.

He had a lot of movie offers by then, though, and he started to think them over. “Steady money,” he said to Ruth. “People even get married, and have homes, on steady money—”

She kissed him. “Go and get it—”

He sent for her after three months, and she came to California. They were married in 1943, by a Los Angeles judge, and everything was great until Richard (he was by then Richard) told Ruth that their apartment was $150 a month.

“You’re crazy,” she said flatly.

After a while, she got used to it. People saying, “Get a Cadillac; better than the Ford.” Or, “Why don’t you buy a house?”

Nicky (he’s still Nicky to her) was doing well. Somewhere in the Night, 13 Rue Madeleine, Walk in the Sun—he kept making pictures for Fox, and they were good pictures, and they brought the money in.

So now she’s used to it. The mail, the cars, the tennis, the flowers, the $200 suits. And the mink coat. Or, at least, she pretends to be used to it.

But sometimes he catches her just stroking its softness, and murmuring, “Nicky. Ah, Nicky.”

THE END

—BY KAAREN PIECK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948