David Niven’s Magging Tales

All my life I have suffered from what practically amounts to a pathological inability to say “No.” I can’t say “No” to film scripts I don’t like. I can’t say “No” to people who ask me out to dinner even when I know perfectly well that I’m going to be in China on the day they suggest. I can’t even fire anybody. I once had a Japanese gardener who used to steal my vegetables and sell them to the neighbours. The only way I ever lost him was when our crops went off and he left for greener pastures. This inability to say “No” has landed me in some strange situations. Once, to my own surprise, I heard myself agreeing to make the film of “Macbeth” with me playing Macbeth. And you can’t get more ridiculous casting than that. I went home and told my wife, Hjordis, who said that this time I had gone too far, and I must call up the producer immediately and put a stop to it. So, I called him up and asked him out to dinner. And after dinner said—“Tell me, are you serious about my playing Macbeth?”

He said indeed he was.

I asked if he’d mentioned it to anyone else. He said indeed he had.

“So,” I said, “and when you mentioned it, have you noticed that their jaws drop like a stone?”

He said now that I happened to mention it, he had. But I w as going to do it, wasn’t I?

“Oh yes!” I said. Hjordis was furious.

In the end I had to cable Sam Goldwyn. to whom I was under contract at the time, and get him to send a very abrupt letter to the producer, saving that I couldn’t possibly be released to do the film. So I got out of that one . . . very “chicken.”

The fantastic Mike Todd

The one time I didn’t even attempt to say “No” and never regretted it, was on my first encounter with the fantastic Mike Todd. The phone rang one Sunday afternoon and a voice at the other end said. “This is Mike Todd. Come right over. I want to see you.”

Normally I never go anywhere on Sundays, but as usual I couldn’t say “No.” So I got out the car and drove over to his place, fortunately having the sense to gather up my agent on the way. He came, but protesting about the ruin of his day off.

Todd was standing by his swimming pool wearing white bikini pants and a big black cigar. “I’m going to make ‘Around the World in Eighty Days,’ ” he said.

“Would you like to play Phineas Fogg?”

Without hesitation I said Id play it for nothing.

“Good.” said Todd. “That’s settled then.” And dived into the pool.

On second thoughts I realized I didn’t exactly mean nothing. though I discovered afterwards that there were actors, top stars, who offered to do just that after I had signed the contracts. So I dragged in my still-protesting agent, whistled Todd ashore, and got the money part arranged.

It took some months before the production got going, and for a while once it did. I began to think that Todd had taken my “do it for nothing” remark seriously. I had no pay for fourteen weeks and we all began to get a little disturbed.

We were in Paris at the time, and Todd said not to worry. Everything was under control. He gathered up his secretary, told her to wear a bright red sweater and parade on a certain corner.

For a while we all thought the worst, and that things must be really rough. But after she’d been there for a bit. a car drew up and a man climbed out and gave her a large suitcase. Opened up, it was full of brand-new, crisp banknotes. This performance went on in Spain as well, but none of us ever knew where it all came from.

The script called for Phineas Fogg to go up in a balloon, and it just so happens that I’m sick if I look out of a ground-floor window. I told Todd that going up in balloons was out!

“Sure,” he said soothingly. “We’ll write it into your contract. How high off the ground are you prepared to go?”

“Four foot, six inches,” I said firmly, “and if you go half-an-inch higher—I’ll sue you.”

“Anything you say,” Todd said, and it was all carefully written into the contract.

I suppose I should have known better. Came the day of the balloon ascent and I arrived at the location to find the biggest crane in the world, 198 feet high, suspended over a two thousand-foot canyon.

“Remember my contract, Mike.” I said firmly, keeping well away from the edge which was making me dizzy.

“Everything’s fine,” said Mike. “We got doubles.”

Well, you could have fooled me. I looked at the doubles for Cantinflas and myself and thought I was seeing orangutans.

Cantinflas looked at them doubtfully. “They don’t look much like us, do they?” he said.

They certainly didn’t. But I was sticking to my guns. “That’s Todd’s problem.” I said.

Cantinflas, who is a very brave man and a Mexican bullfighter as well as an actor, said. “I think we’d better do it ourselves.”

“I,” I said, “will personally murder you if you get into that balloon.”

The orangutans climbed in. The effect was ridiculous.

“Gee, boys,” said Todd. with what looked suspiciously like a smirk on his face. “I don’t think it’s going to work.”

Without a word, Cantinflas climbed in. That just left my orangutan. Todd still wasn’t saying anything.

Well, what could I do? The whole honor of the Anglo-Saxon race was at stake. Todd was standing there grinning, surrounded by two thousand American extras.

“Ali right,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

“That’s my boy,” said Todd. “Anything we can do to help?”

“Yes,” I said. “Get me a bottle of brandy.”

That scene was played. swaying over a 2000-foot drop, on the entire liquid nourishment of a bottle of Hennessey Three Star. It’s probably the most drunken scene ever filmed—but it didn’t show.

And that will teach me not to believe in odd clauses written into contracts.

Another time he landed me into playing a scene with some of Britain’s finest stage actors—people like Trevor Howard and Robert Morley—with sixteen pages of dialogue to learn on an airplane. Personally, I can’t even read, let alone learn anything on planes, and I arrived unprepared.

We did the scene with my dialogue written on bits of paper all over the place. Some of it was on the other actors’ shirt fronts. I could mentally hear all of them muttering to themselves about “damned Hollywood actors.”

Todd had the most fantastic methods of getting his own way. When we were filming the sequences when the dreaded balloon was floating gently over Paris, Parisians were standing about gaping at the pretty sight, and getting mown down by the traffic like flies. So the police said enough was enough, and arrested the balloon and the taxi that towed it.

Todd was livid. He still had one more shot to get with the balloon floating over the Place Vendome.

The poliçe had mounted guard around the taxi with the balloon tethered to it, and I couldn’t for the life of me see how he was going to get his last shot.

But he did.

He bought two taxis and their drivers and paid them to run into each other and have a terrible accident on the other side of the square. They were game for anything, the money Todd was waving around. They hit each other head-on with a sickening crunch. Every policeman for miles rushed to see what was happening, and as they ran, Todd signalled the driver of the balloon taxi which whipped away and with the camera turning, got the last shot.

What patriotism cost me

At one point in my career, after having been right at the top, I just didn’t know where the next film was coming from. For eighteen months I really thought I was finished.

Up to a point it was my own fault. As a British subject—I still am and always will be, even though I live abroad—when the war started I became very excited about the whole thing, started to wave a sword wildly and took myself off to Britain to fight for home and country.

Financially the whole expedition was disaster, though I’d do it all over again. Sam Goldwyn, to whom I was under contract at the time, was so annoyed at losing one of his stars by this foolhardy display of patriotism that he promptly suspended me—which meant no pay.

I was away for six and one-half years, and when I came back Goldwyn insisted on taking up my contract where we had left off. I still had five more years to go.

I wasn’t exactly happy about the films he was putting me in, and rebelled violently. And worse, I believed my own publicity . . . that I was God’s gift to Hollywood.

So one day I stormed into Goldwyn’s office, and demanded to be released from my contract.

He looked up and said—“Right, you’re out. That’s as soon as you hit the street.”

I must say I felt he had given in a little easily, but was still pleased to have my freedom until I found that other studios were not exactly breaking their necks for my services.

And then it began to dawn that perhaps all those publicity statements weren’t so accurate. I did one more film for Goldwyn, and he certainly got his own back. It was an all-time stinker, called “A Kiss For Corliss” which I made with Shirley Temple. And after that—Silence!

I work on the theory that when things are at their worst, that’s the time to do something really spectacular.

So one day I said to Hjordis, “Come on—we’re going on holiday.”

I packed her and the two boys up, drained my bank account down to the last cent, and went off to Barbados, where we had a wonderful time. I had every intention of selling the big house on Pacific Palisades when I got back, and starting all over again.

But it didn‘t work out like that. When I came back I was approached to do a play on Broadway. Not that I’d ever acted on the stage in my life, but I was prepared to have a go. It seemed like a good moment for a gamble—win it or lose it.

Whalebone up my nose

It was a play called “Nina”—a French farce. So French it completely baffled the New York audiences who saw it. And my leading lady was Gloria Swanson, who had just had a huge success on Broadway.

I played the lover. Gloria was my mistress and Alan Webb played her husband. See what I mean? Typically French.

On the first night I made my entrance practically speechless with nerves. There was a glossy and expensive first-night audience in front with friends like Rex Harrison, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh who really knew what they were doing on a stage. That made me feel even worse.

Gloria Swanson at that time had a business interest in a fashion house. On account of this, she was allowed to design and wear her own clothes for the play.

She appeared wearing what I can only describe as a tremendous black taffeta tent.

Shaken by this apparition and nervous anyway, I grabbed her to kiss her (part of the script) but grabbed too hard. She wasn’t easy to find under all that taffeta. There was a sort of twanging noise, and up from the front of her dress shot a length of whalebone—straight up my nose.

Not only was this disconcerting, but painful. It had gone so far I couldn’t disengage myself. Thinking hopefully that perhaps it didn’t show from the front, I tried to play the love scene, tears streaming down my cheeks.

Eventually by standing on my tip-toes, I managed to disencumber myself, but there it was, yards of whalebone sticking into the air with Gloria quite unconscious of anything.

Desperately I pushed the runaway stay back down the front of her dress and she squeaked. The audience, who up until then had sat in unbelieving silence, burst into roars of laughter.

But the whalebone kept bobbing up again. Finally, the only thing left to do was to pull it out completely. And there I was left with it in my hand. The only thing to do seemed to be to wave it triumphantly. The audience applauded madly.

The next morning one New York critic said, “I understand from the programme that Miss Swanson designed her own clothes. Like the play, these came apart in the first act.”

Needless to say, “Nina” had a very short life and her demise after twelve weeks was merciful. And there I was facing the breadline again.

But fortunately for me, Otto Preminger had seen the play and must have spotted something in it that no one else did. Because he offered me the lead in “The Moon is Blue” and fortunately for me, that turned out to be a big success.

When things are at rock-bottom, they can only get better. Just before “The Moon is Blue,” Charles Boyer and Dick Powell suggested I might like to join them in a new television company they were starting.

I was keen, all right. This was something I could do. Something I could get my teeth into. I coughed up my share of the starting money—about £2000 I managed to raise, and we were away with a Capital of peanuts—£6000.

We made a pilot for a series called “The Four Star Playhouse” and sold it to Singer Sewing Machines—and we were off. The trouble was, we hadn’t a fourth star, and at that time television was poison to film people. No one would join us. They were all scared of the enemy.

Finally Joan Fontaine agreed to do just one play, and we suggested to our sewing machine sponsors, very cunningly, that we had a different fourth star every week. and let the audience be surprised at what turned up.

Surprisingly, they fell for it.

Tears at M-G-M

We nearly all went berserk, rushing about, running the company and starring in scripts ourselves. We were making our films with a three-day schedule, and it was all something of a panic, particularly as we were short of money, but used to doing things on a typically colossal Hollywood scale.

About this time Louis B. Mayer, head of M-G-M, sent for me. He was crying big tears. Louis always cried.

“David,” he said, “we are the studio that gave you your first test. We gave you the break. Now I hear you’ve gone over to the enemy. You’re making TV films. I beg you—don’t do it.”

Biting back the impulse to tell him I hadn’t worked for M-G-M for eight years, and that they’d never used me after that initial test, I said mildly I was very happy and intended to go on making TV films.

Mr. Mayer’s face hardened. The tears miraculously dried up. “Then you’ll never set foot again in my studios,” he said.

I didn’t for a long time, but then I did three films for M-G-M. Television is now respectable.

Actually, I’ve been fantastically lucky. It’s not everyone who gets a second chance. and the opportunity to start again. I’ve almost had two separate careers—one before the war, and one after.

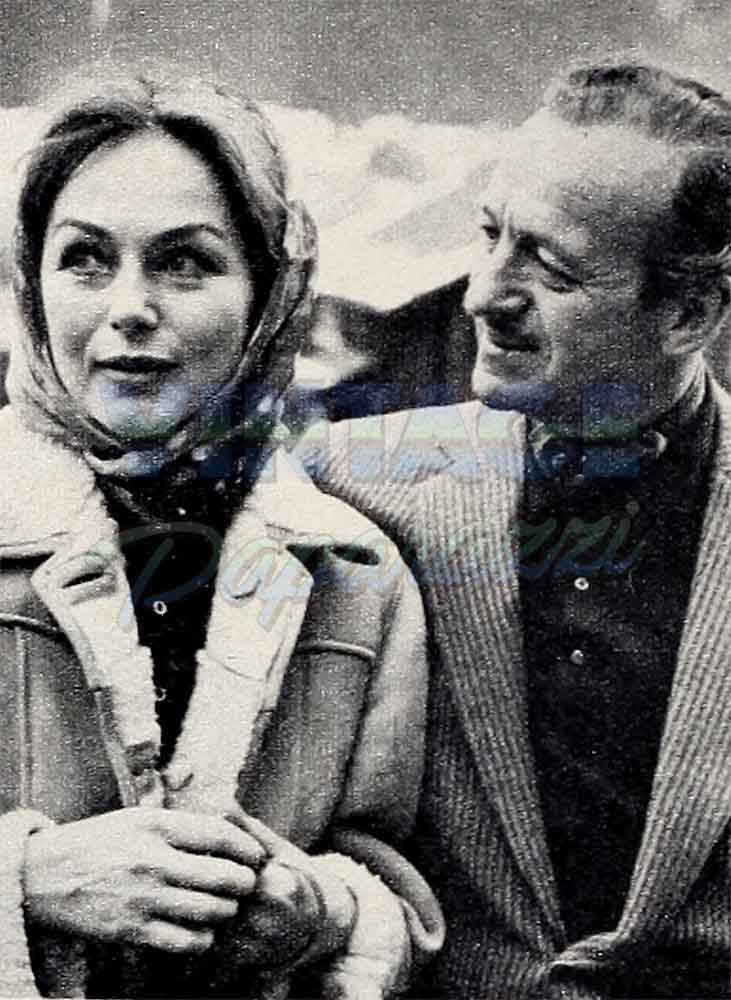

I’ve been lucky in love. Too.

After I lost my first wife, I was fortunate enough to meet Hjordis, my present wife.

I’ve always been married; I like it that way.

Hjordis and I have been together now for thirteen years. She’s Swedish; I’m British; we live in Switzerland with my two sons . . . true Internationals.

It’s a good life! I am very lucky!

—As told to UNITY HALL

David stars in “55 Days at Peking” and “The Pink Panther” for United Artists.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1963