For Sale: One Pair Of Traveling Boots—Kirk Douglas

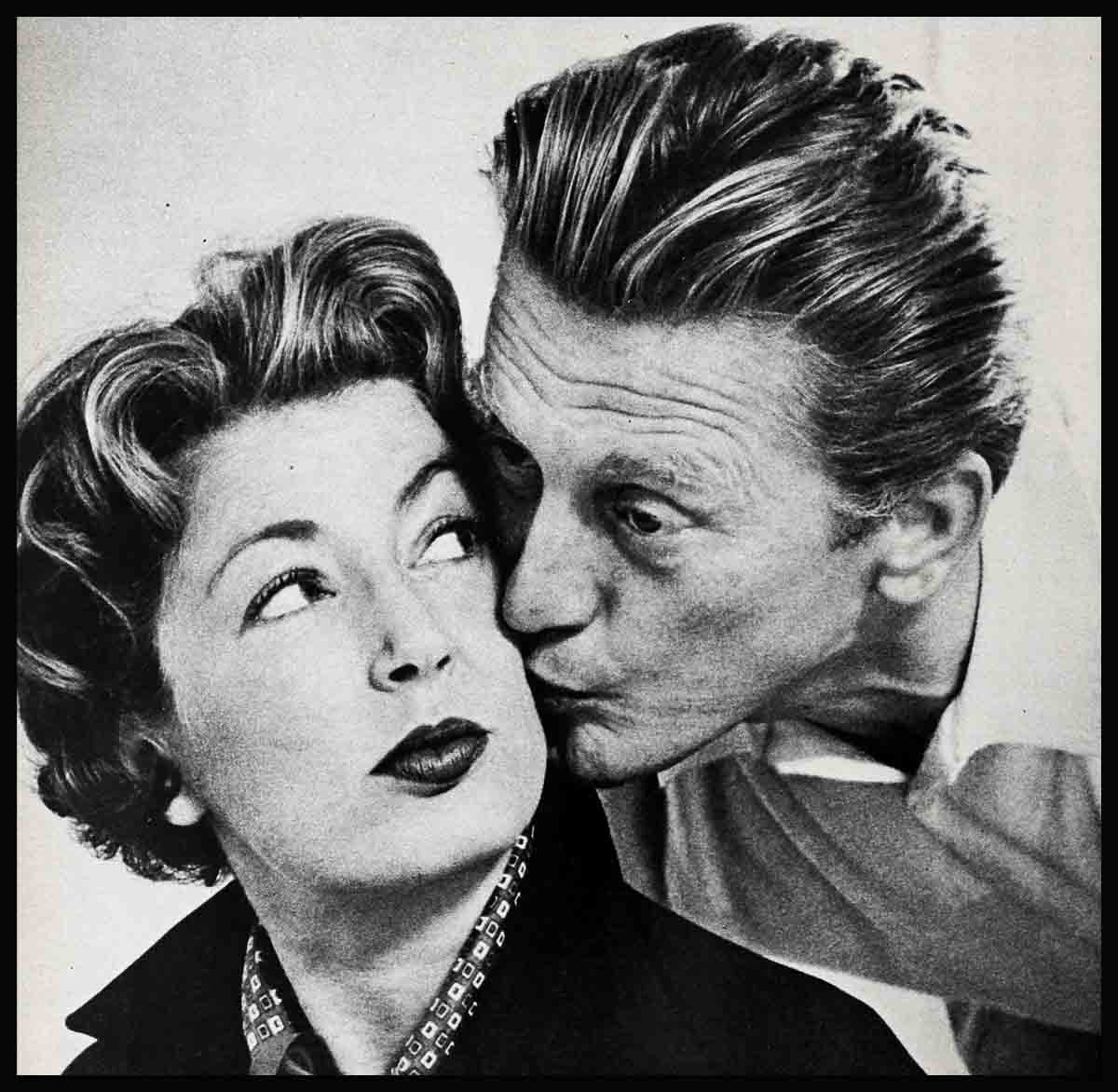

His chair tilted back against the wall of his tiny office, Kirk Douglas, full-time actor and part-time producer, sat relaxed in slacks, sport jacket and polo shirt, the picture of a contented man.

The office was his own, headquarters of his newly formed Bryna Productions, dedicated to the filming of at least six independent pictures under Kirk’s own banner. His hair was still damp and his face ruddy with a steam-room glow; he was fresh from the gym where he had worked out for an hour. He chuckled in reminiscence at the comment of a fellow independent, Otto Preminger, who had said wryly, “Kirk, you’re the only producer at this health club with real muscles.”

“But here’s the thing,” said Kirk. “A year ago you wouldn’t have caught me dead in a gym. It would have seemed a waste of time; there were too many other things to be done. Or, if I did go, I would have used the gym to try to prove something—what, I don’t know. But I’m beginning to take a breath now and then; I’ve stopped running so fast. I’m no longer tilting at windmills, trying to knock them over just because they’re there. Now I know you can’t bull your way through every wall that gets in your path. Sometimes you have to go around it or even wait for the wall to fall down by itself.”

For Kirk, of course, the lean years are long since gone—the long, lean years when the boy from Amsterdam, New York, was fighting to overcome something: poverty, lack of opportunity, the pain and hurts of the things he hated in his youth. His fight seemed more against things, than for something concrete, positive, constructive. He was the man without a star, a kind of wanderer without a positive philosophy of living, too busy carving out success for himself to really live.

He remembered starting to work even before he started in school, “running errands for the guys down at the carpet mill.” When he was seven he was already in business, getting up at five a.m. seven days a week to meet the train from New York, to pick up and deliver the city newspapers, returning home, if he was lucky, by 7:30 at night.

At his house the cupboard was always bare, or so it seemed, and there was hardly ever anything in the icebox—sometimes nothing but a can of cooking oil, the smallest size. Said Kirk, “It drives me crazy today if the refrigerator at my house isn’t crammed with food. When I go to a fancy dinner party (I have a complex about food) or an expensive restaurant, I feel I have to eat everything on my plate. I can remember too well when there simply wasn’t enough to eat.”

There was also in Kirk—for a long time, anyway—a terrible urgency to get going, to work, to run through life as fast as he could towards the things he wanted. There seemed never time for real happiness; he was always waiting for the time when he could “afford it.” For a long while, too, all that mattered to Kirk was success. Not the work he did, only the success from it. What seemed to mean most was what people might say about his work, not what the work itself said. And he wanted to be admired and loved, just as everyone wants to be loved. But there was a hitch. He wanted to be loved just for himself.

So this was the way Kirk was building his life, unconsciously spending time and energy getting “even” with what had hurt him in his youth. He had nothing left for creating happiness in the present. And then he met a girl named Anne Buydens in Paris—met her, fell in love and asked her to be his wife. They were married in Las Vegas, Nevada, May 29th, 1954, and came back to a house Kirk had bought in Beverly Hills—the first house he had owned in his life. He said goodbye to wanderlust and settled down—with Anne and his two boys, Michael and Joel, sons of his first marriage, whose custody he shares.

Today he has his own home, his own production company, his name on an office door and many lessons learned. A thoroughly happy man? “No,” smiled Kirk. “Who is? But say I’m almost happy—anyway, ninety-nine and forty-four one hundredths per cent. And I’ve discovered when not to fight. I’ve found out how wasteful it is to create opponents, get mad without reason.

“How many times in the past would I make an appointment to go in and see a producer about a part and then start building up anger in advance, feeling sure the part he intended offering me would be too small? Even before I’d go in I was already mad, and for nothing, no reason at all.

“But I’ve learned there’s no percentage in that anymore. It’s like that wonderful story that Danny Thomas tells, about the man who gets a flat tire on a lonely road at night and has to find someone from whom he can borrow a tire jack. The man starts down the road looking for a garage, telling himself that the owner of the jack will probably want at least fifty cents to lend it. The farther the man walks, the higher the imaginary price rises. Pretty soon it’s a dollar, then one-fifty, then two dollars, and he’s getting angrier and angrier at the thought of anybody asking that much just to lend a jack. And remember, he hasn’t even found a garage! After about an hour of walking, the man is just beside himself with self-pity and anger, and in his own mind the price for the loan of the jack has risen to an outrageous figure.

“Finally, and at long last, the man finds a garage. He knocks on the door. When the door is opened, does the man with the flat tire explain his predicament? No. ‘Robber, thief, highbinder!’ he screams at the mechanic before he can say a word. ‘Pay you five dollars for the loan of a lousy jack? Never. Keep your jack, you crook; I’ll see you in hades before I borrow anything from you!’

“Well,” laughed Kirk, “I was like that man who needed the jack. Boiling mad and without good reason. One day I stopped and asked myself, ‘What are you fighting against? Why must you be a Don Quixote all the time?’ And finally I learned just to walk in and say, ‘Please, sir, may I borrow your jack?’ Simply, just like that. No fighting, no building up anger in advance. I started taking inventory of myself. I mellowed, began to take a quiet breath now and then, instead of running nowhere at full speed. Finally I became aware that when I was aggressive, always fighting, I wasn’t really enjoying my life.”

It takes an honest man to admit all this, and Kirk Douglas is an honest man. Long ago he discovered that something happens to dreams when they come true. “Did you ever try to catch a snowflake?” he asked. “Once you put your hands on it, it’s gone. A dream is just as fragile and dissolves as soon as you attain it. Yet a man must always have a dream, a goal, an ambition—or his life is just a series of aimless wanderings.”

So, always he fought and, fighting, wondered why all the success didn’t add up to happiness. He was forever The Young Man in a Hurry. Life couldn’t wait; it had to be now, now, NOW. “Kirk,” said a close friend, “learned to play the banjo, for instance, in two weeks, when other people would still have been mystified by the fingering. He learned juggling the same way (it was for a role in a picture)—quickly, at a hundred miles an hour. He learned the harmonica, tennis, skiing, boxing, French, Hebrew, Italian at the same speed —furiously, almost violently. Once, in Switzerland, when he was taking skiing lessons, he couldn’t seem to get the knack of a certain turn. The instructor tried to tell him it would take time, it couldn’t be learned in a moment. ‘No,’ said Kirk, clenching his fists, ‘make me do it. Make me do it!’

“Another time, in New York, he went to dine at the Colony with some friends and insisted on speaking French. When the friends suggested that English would be perfectly acceptable, Kirk declined to yield, ‘No, I want it this way,’ he insisted. ‘How else can I learn?’ With Italian it was the same. He wanted to use his talents, always wanted to use his talents.”

It was, of course, this same intense drive of Kirk’s that led him to become what he is. Born the only boy in a family of six girls, of parents who were Russian immigrants, Kirk received none of the coddling and spoiling that usually goes with being little brother to a lot of girls. At high school he led assemblies, won oratorical contests, recited poetry, staged plays and did his share on the debating team. At St. Lawrence University, to which, as has been told before, he hitchhiked atop a load of fertilizer, Kirk worked as a part-time waiter and still found time for sports, becoming, within a few months, the college’s undefeated wrestling champion.

During his senior year he was Student Body president, Campus Council president, president of the Dramatic Society, president of the German Club and president of the National Student Federation of America. During the lean years of his theatre training and apprenticeship in New York, he was a wrestler with a carnival, bellhop, punch press operator, parking station attendant, waiter and usher.

With a background like this, with an ambition and a drive so unrelenting, Kirk was catapulted to stardom with his performance in “Champion.” Describing the Kirk Douglas of that period, one writer said, “His was not a new face in Hollywood, but there was something about his remarkable portrayal of the fighter to whom nothing was important except to win. He played a vicious man with such insight that audiences, understanding Midge Kelly,pitied him.”

So, too, was his way of immersing himself, body and soul, heart, spirit and ambition, in every role he later essayed. He studied for three weeks with Harry James to learn trumpet fingering for “Young Man with a Horn.” He worked as a general assignment reporter on the Los Angeles Herald-Express prior to starting a newspaper picture, “Ace in the Hole.” And before he would even tackle “Detective Story,” he spent considerable time with New York detectives and then played the role on the stage in Phoenix to become better acquainted with the character.

These things were all constructive in aim; they were part of his job to make himself a better, more successful actor. But there was also the all-pervading ambition, the fighting for the sake of fighting. Yet success didn’t add up to happiness, and he wondered why. The dream he had driven himself all his days to achieve wasn’t quite good enough. There seemed something more important in life than merely to win.

“When you’re young,” said Kirk reflectively, “you’re always thinking: Ive got to get a job, make some money, go to high school, finish school, be a big man, hitch a ride somewhere, get to New York. It’s fight, fight, fight all the time. You’re bursting with the need to arrive someplace, be somebody, no matter how. After I got the part in ‘Champion,’ I thought I had fulfilled the dream. I had broken through the barriers, many of which I had set up myself. It was no longer a question of getting somewhere. I had arrived; I’d clicked for the time being. And still I hadn’t proved anything to myself. I found I was more loused up than I’d ever been. I was fighting to retain the values I’d set for myself, but I discovered that I’d merely been slashing at daisies. It was as though I’d been robbed.”

Kirk was silent for a moment, seemingly lost in the past. “Look,” he said at last, “you fight to become something, to become a person, gain dignity as a man. You feel a lot of things you desperately want to express. Maybe you can express them only by being forceful and over-aggressive That’s wrong, I know; it’s not constructive. And yet I must say this: I was never fighting for material things—the biggest house, the biggest car, the biggest wardrobe. I never thought in terms of wealth; I was a kind of rebel without a cause, fighting to express myself creatively, to say what I had within myself.

“Why once,” laughed Kirk, “my family came out here and were actually disappointed at the size of the house I was living in, it was so small. And every secretary I ever hired owned a better car than I did; it became a kind of standing joke. Now, finally, I’ve got a better car than my present secretary; maybe that’s why I like her so much!

“But anyway, there comes a time when you learn you’ve got to operate on a different basis, you just can’t keep knocking things down, and then you ask yourself: where do I go from here, what do I replace those early fights with? That’s when you really have to come up with the answer.”

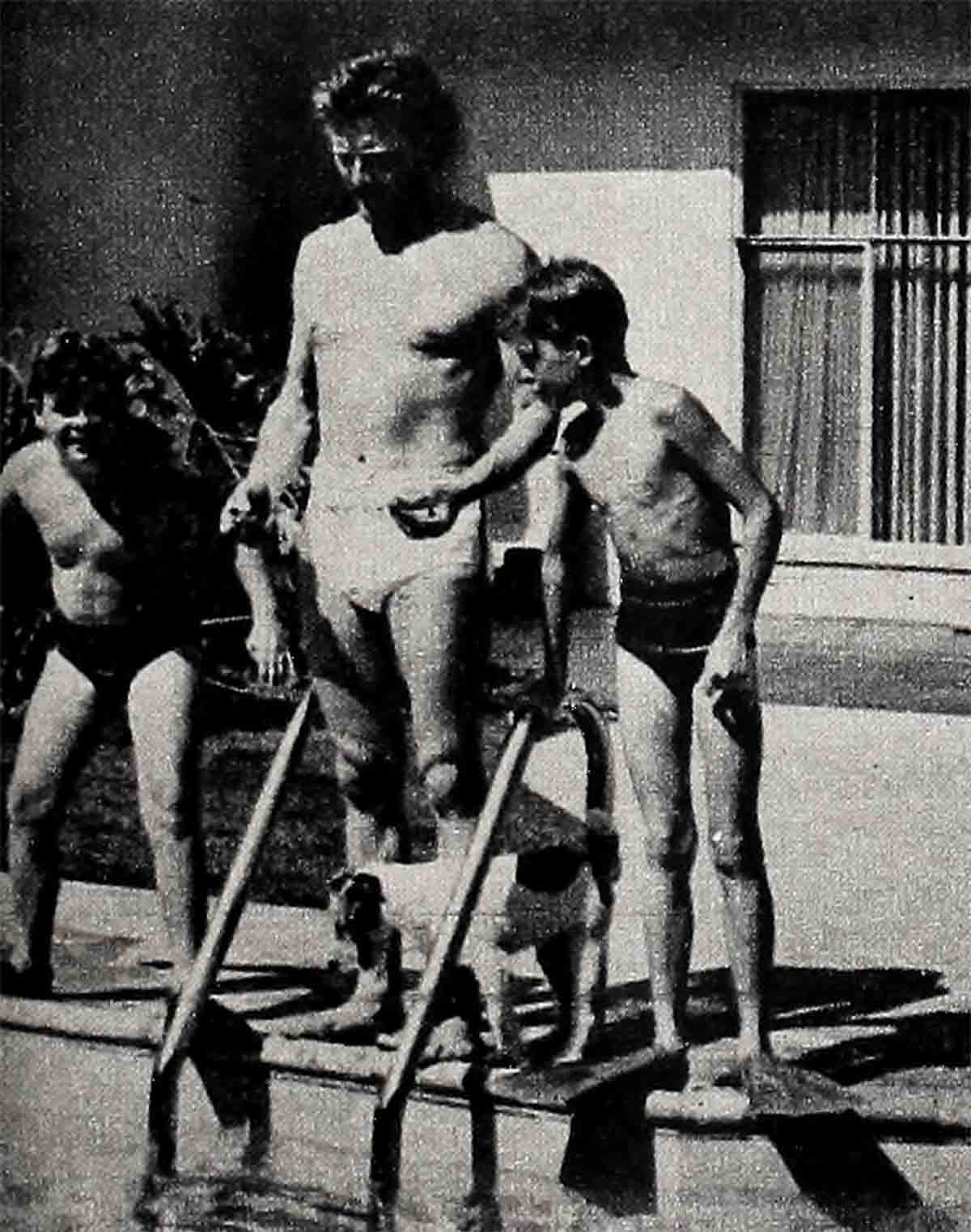

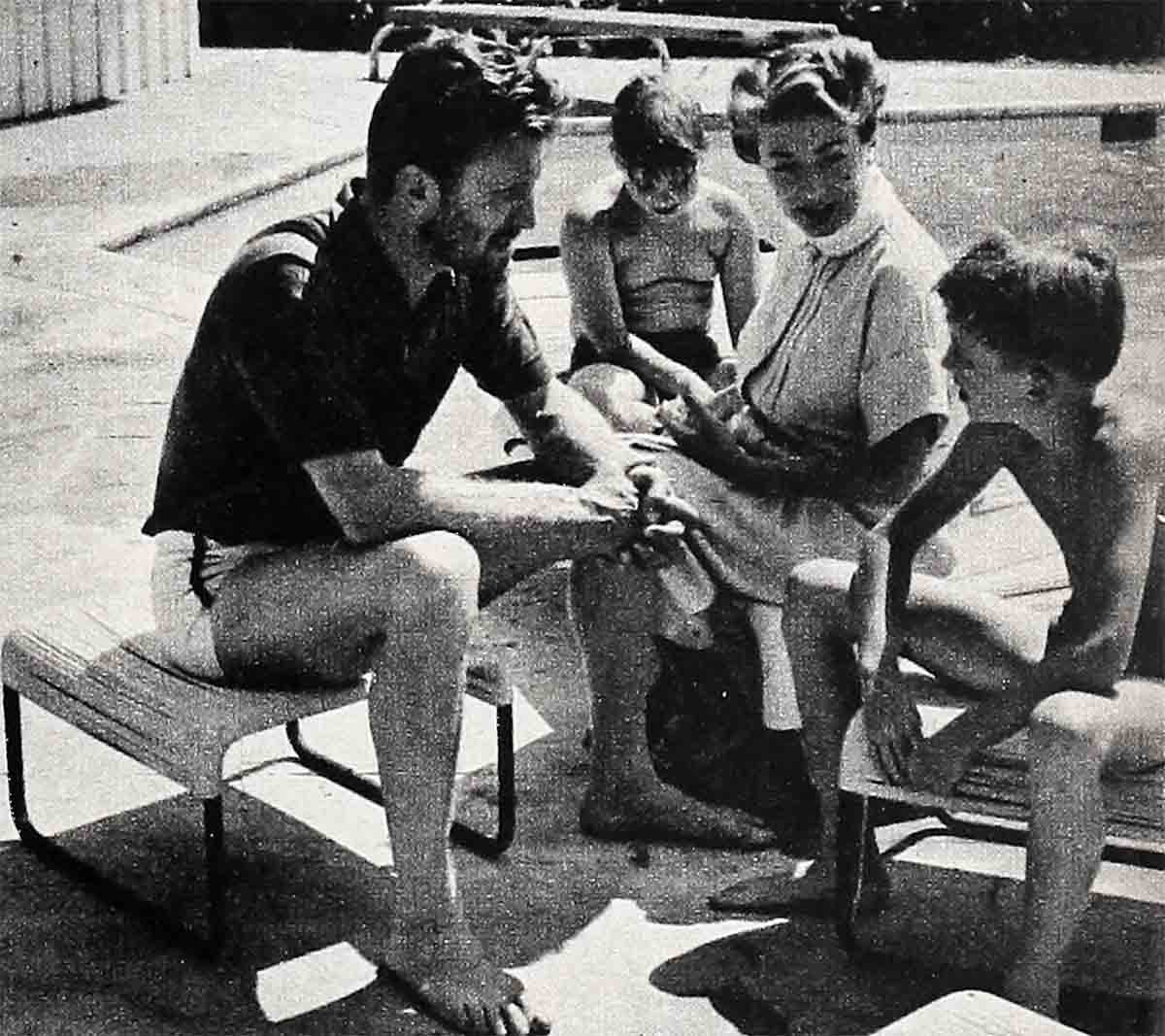

Well, Kirk seems to have found the answer—in Anne, his wife, in his sons, Michael and Joel, who are nine and seven and spend a lot of their time with him; in charity work; in his newly formed Bryna Productions, named after his mother; even in workouts at the gym that help channel his drives. Constructive things—things for something, instead of against them some- thing positive.

There was, as Kirk explained, no one day when the light broke; it was a matter of learning over the years. Meeting Anne helped; his travels in Europe taught him much, making him aware how many things he had in America without even the necessity of fighting for them. And then there was just the sheer process of growing up, discovering for himself that there are others in the world beside himself.

“Kirk’s wife,” said a close friend, “has helped him immeasurably. She has much wisdom. She’s pulled him out of that fighting mood, taught him to be patient, to give up things when necessary. Right now Anne is not only reading scripts for Kirk’s new company; she’s also busy with a new project at the house, making over a bath house behind the swimming pool into a guest house for Kirk’s boys when they come out to spend the summer.

“Then, too, Kirk’s been working six days a week on his production company’s affairs; it’s kept him jumping. Not only has he had to be star, producer, writer, casting director and script editor; he had to be office-looker, too, finding an office where he and his staff could headquarter. It’s lucky he is so busy; if he weren’t, he’d go crazy from inactivity. Kirk never smoked, but this whole business of getting his own company under way has changed him so that he has even started smoking. Someone handed him a cigar one day and he actually accepted it. Of course, he took just one puff, but he took it. Another thing he hates is using the phone. Yet I came in one hectic day and found him with a telephone receiver at each ear, trying to talk business with two different people at one time. Then I knew he’d had it.”

Kirk roared, hearing this apt description of himself. “Well,” he said, “that proves I’ve changed, doesn’t it? Well, I’m doing my best to change—to do what’s constructive and I think I’m slowly succeeding.

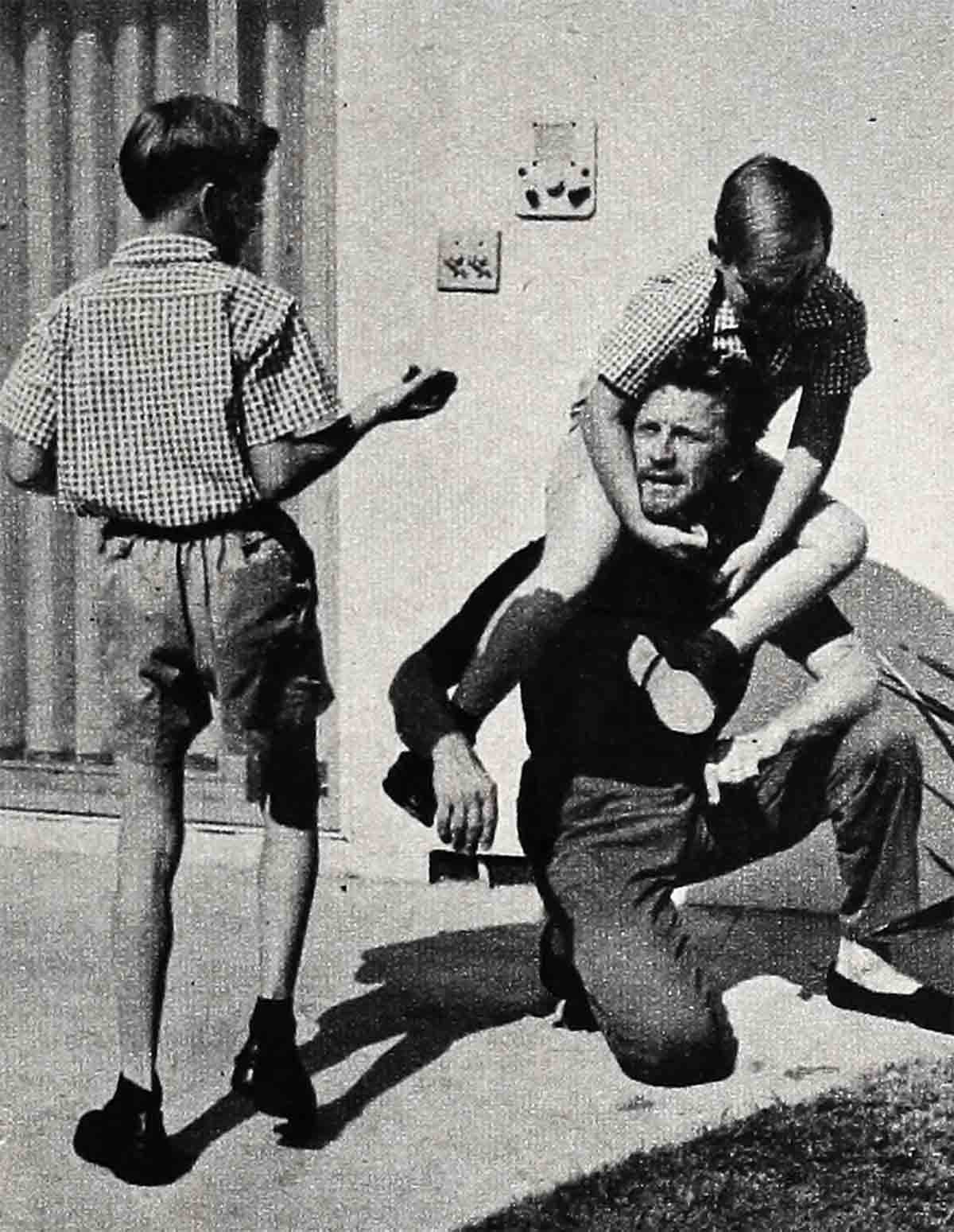

“For instance, not long ago my boys were out here on their regular visit. One day we were playing handball, Mike and Joel and I, and I guess I started favoring Joel, the younger one, a little—feeding the easy balls to him, instead of to Mike. Mike got angrier and angrier, until at last he couldn’t take it. He ran at me in a rage, flailing with both arms. But there was no point in punishing him. I knew he had to work off his aggressions, just as I did. So I talked it over with him quietly, because, being a child, he just didn’t know how to react. Later he came to me and told me he was sorry. I told him I understood. ‘Look,’ I said, ‘you don’t have to like me all the time.’ Anyway, it taught me a lesson, too—taught me to be reasonable. Poor Mike also had to learn how to channel his aggressions.”

Discovering himself through others—that’s been Kirk’s big lesson. Still a rebel, yes—but a rebel with a cause. He admits that he is still like a volcano: quiet for the time being, but with the knowledge that should things go wrong, he may explode again. But right now he’s working not only for his happiness, but for Anne’s and his sons’, and for the new baby due to arrive in the fall. Fighting for something now, making his peace with himself and his world.

And, as Kirk says, “Just learning to walk in and ask, ‘May I borrow your jack?’—simply, without building up anger in advance. That’s been the greatest lesson. It’s the answer to my search. For me, anyway.”

THE END

—BY MAXINE BLOCK

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955