Jerry Lewis Helps Answer A Little Boys Prayer

The little boy gripped the arms of the wheel chair and turned his head away. Now he couldn’t see the jumble of letters and cards and torn gift wrappings that surrounded the other kids. But he could still hear their loud, happy voices as they jabbered away to the parents and friends who had come to visit them at the Massachusetts Lakeville Sanitarium for Handicapped Children. “So what,” he told himself. “I don’t care. I don’t need . . .” But he did care—oh, ever so much—and his need was even greater than any of the others’. His big brown eyes were wide with tears and they fell unheeded down his cheeks and onto the striped pajamas. He hated himself for crying, and that only made the tears come faster.

“What’s the matter, Little Boy Blue?” a gentle voice asked.

The boy looked up and saw his friend, Mrs. Shaw Reynolds. He tried to answer but he just couldn’t.

She touched his face lightly and her hand, as always, felt cool and nice. He let his face cradle against her fingers and slowly his crying stopped.

“That’s better,” Mrs. Reynolds said, “much better. You want to be a great jet pilot some day. And you know jet pilots don’t cry. Can’t see the instrument panel through tears, can you?”

“No,” said the boy, “you can’t. But I’m not a pilot yet. I’ll have to wait till I’m big, big like Dr. Jellinek, before I can fly. But I’m getting bigger and bigger. Why, I’ll be nine years old Tuesday. Won’t I?”

“Yes, you will . . . on Tuesday,” Mrs. Reynolds said. And then the little boy looked away from her, back at the other kids.

She watched him as he watched the others. The expression on his face as he looked at the children playing with their toys, reading their cards aloud, and talking with their mothers and fathers, was heartbreaking. It was bad enough, she thought, that Little Boy Blue (the hospital records listed him simply as Francis X.) was suffering from muscular dystrophy and that his case was incurable, although, thank God, he didn’t know he was going to die But even worse, in a way, was the fact that no one came to see him, no friends or relatives. The other children received postcards, presents, letters, and love . . . he received none of these.

Mrs. Reynolds wheeled Francis back to his own room. Carefully she helped him into bed. She sat down next to him and brushed a wisp of hair back from his forehead. He smiled at her for a second, and then he started saying his prayers.

“Dear God ” he prayed, “this birthday, please have someone send me some cards for my birthday . . funny cards with clowns on them . . . not many . . . just a couple. And God bless everyone specially Mrs. Reynolds and Dr. Jellinek and Jerry Lewis. He’s funny . he makes me laugh. Good night, God.”

Mrs. Reynolds turned out the light and bent over and kissed the little boy. Softly she said, “Little Boy Blue come blow your horn. The sheep’s in the meadow, the cow’s in the corn. And where is the boy who looks after the sheep?”

And Francis whispered. “He’s under the haystack, fast asleep.”

Mrs. Reynolds left the room and went in search of Dr. Jellinek. That night the two of them made a couple of telephone calls, one to Henry Bosworth, a feature writer for the Boston Herald, and the other to Jerry Lewis, national chairman of the Muscular Dystrophy Association, in California. And Mrs. Reynolds and Dr. Jellinek told both men about Little Boy Blue and his prayer.

After Jerry hung up the phone, he sat for a moment looking blankly at the far wall. Then he picked up the picture of Patti and the boys from his desk. He gazed at the face of each of his sons as if he were seeing it for the first time. One little boy. One little boy. Each of his own youngsters was one little boy. More precious to him than anything, more precious to him than life itself. And in Massachusetts, another little boy, one little boy, was dying but didn’t know it, had a dream but didn’t think it would come true.

Jerry heard the front door bang closed. “Gary,” he thought, “Gary . . . Who else bangs the door?” And aloud he called, “Gary, that you? Back from the game already?”

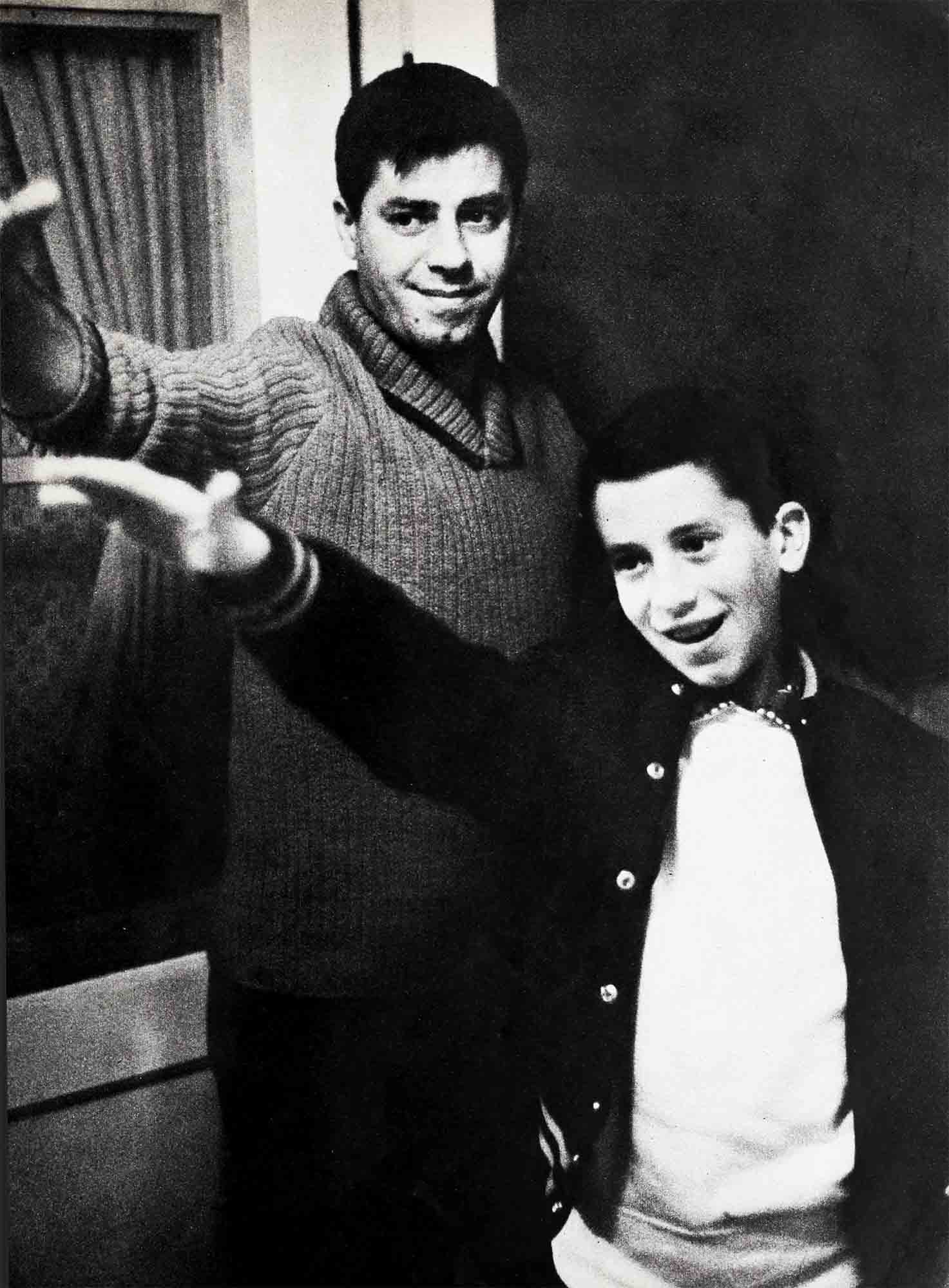

His son came into the study. Jerry stared at him, studying every feature of his young face, noticing the glow of health and the smile of happiness he saw there.

“What’s wrong, Pop,” Gary asked, “Why are you staring at me? Did I do something wrong?”

“Nothing,” Jerry answered, “nothing. I was just remembering that you were once a little boy.”

“Huh?”

Then Jerry told him about the phone call he had just received, and about Little Boy Blue.

For a second, Gary said nothing, but just for a second. “But Dad, that’s awful . . . terrible . . . I mean can’t we do something about it?”

Jerry smiled for the first time since he’d received the phone call. “I’m glad you used the word ‘we,’ ” he said. “Yes, we are going to do something about it We’re going to see that Francis has the riproaringest birthday party a little boy ever had. And you’re my number-one assistant in charge of practically everything.”

Jerry glanced at his calendar and grunted, “Just a few days . . . some commitments I just can’t get out of. But we’ll do it Somehow we’ll do it.”

The first phone call he made was to New York City, to General David Sarnoff, head of RCA and NBC-TV He asked that an hour and a half closed-circuit TV time be made available from Hollywood. California, to Lakeville, Massachusetts, on the afternoon of Tuesday, October 7th. While the General was still sputtering “impossible,” Jerry told him all about Little Boy Blue. All the gruffness went out of General Sarnoff’s voice and he said gently. “Okay We’ll do it.”

Then Jerry and Gary divided up a list of names Between them they had all the top entertainment figures in Hollywood. Jerry made calls from the study and Gary made calls from the other phone, in the living room. At one point, Jerry took a break and went in to see how Gary was doing. The boy was saying. “. . . this means everything in the world to him . . . he thinks nobody cares . . . that must be awful. Okay? You will? Gee, thanks. And my father thanks you, too.”

Jerry tiptoed from the room and returned to his study. He made more calls In half an hour or so he and Gary tallied up the results. The stars were coming! Little Boy Blue would have the rip-roar-ingest birthday party ever.

Now Jerry made the final call of the evening, to Lakeville again, and told Mrs. Reynolds and Assistant Superintendent Jellinek that the party was definitely set for 5; 30 p.m. on Tuesday, October 8th.

Then he and Gary had a glass of milk and went to sleep.

Back in New York, General Sarnoff was already at work. He authorized the expenditure of $100,000 to transform Lakeville into a television relay station. Swarms of technicians were sent into the area and power lines were erected almost overnight.

Meanwhile, Henry Bosworth of the Herald went to the sanitorium and interviewed the medical staff, the patients, and Little Boy Blue. Then he went back to his office and wrote the story of the dying boy who just wanted a few birthday cards. And the article appeared in the paper.

The results were immediate and overwhelming. The wire services picked up the story and it appeared in newspapers all over the world.

Thousands of cards poured into Lakeville. A trainload of toys came from Germany.

Birthday cakes arrived by mail, by express. and were delivered by hand.

Letters flowed in—many of them containing money—so that a special trust fund had to be set up in Francis’ name.

Francis was unaware of all the commotion. He just lay in bed and stared into space.

Out in Hollywood, Jerry Lewis had cleared his calendar. Twenty-four hours before the special telecast was to go on, he sat down with songwriter Sammy Cahn to write the songs, the parodies, the orchestral arrangements, and the special sketches. They worked through the night. Gary refused to go to bed. He brought them coffee and sandwiches. He copied over the routines. He helped in every way that he could.

At dawn, the last word was put on paper. Then Jerry and Sammy went through the whole show, playing all the parts, singing all the songs Gary sat there, trying to think and feel and react like Little Boy Blue would think, feel, and react. At the end he was smiling and clapping. “Great,” he said, “great. He’ll love it.” And he went over and hugged his father.

At 10 a.m. some of the most, famous names in show busines gathered on the TV sound stage. Jerry, who had just taken enough time out to shave and shower, stood before them. Gary sat sleepily in a corner.

“You all know why you’re here, otherwise you wouldn’t be here,” Jerry said. “I just want to tell you that I thank you, Gary thanks you, and Little Boy Blue thanks you. End of speech. Let’s go to work.”

In Lakeville, Francis had found out he was going to have a party. Too much was going on to keep the secret. Cards were suspended on strings in the auditorium. Balloons hung from the walls. Huge TV sets were placed around the room. Mrs. Leo Gibbons, party supervisor, and her helpers, women from nearby Middleboro, set the punch, ice cream and fruit out on tables. Four huge birthday cakes were arranged against a floral design of bronze chrysanthemums and huckleberries. Volunteers were still working on the 147 mail sacks—literally two tons of mail, containing 200,000 cards and letters, and more than $10,000 in cash.

Yes, Little Boy Blue had found out. Proudly he invited the other eighty children and the hospital staff to be his guests. When he was told about all the gifts, his eyes widened and he said, “Good. Now it can be everybody’s birthday. Let’s all share everything.”

Four hundred GI’s in Alaska sent 400 presents. And 400 more came from GI’s in North Africa. Fifty smaller cakes and enough toys for more than a hundred kids waited in the auditorium. Ted Williams sent an autographed baseball; a model jet plane and a jet pilot helmet were personally delivered by three Otis Air Force Bass pilots; a football signed by the Boston College squad and a special record cut by Tennessee Ernie Ford—“For Francis from Old Ern”—were on one of the tables.

At three p.m. the eighty youngsters were wheeled in beds or chairs to the auditorium. The last to arrive was Francis. Mrs. Reynolds wheeled him through the rows of happy children while they sang, “Happy Birthday to You.” He was excited, pink and shiny. Francis’s first birthday party had begun.

Now came the rustle and rip of tearing boxes, then the squeals of delight followed. Suddenly it was like Christmas in October. The punch, ice cream and fruit came next. Around five the harried staff straggled in. By five-thirty, Francis X could hardly restrain his joy. He stared at the TV screen. Here, any minute, would be Jerry Lewis putting on a birthday show just for him. The lonely little boy who thought nobody loved him leaned forward eagerly in the wheel chair, his heart pounding. His gay pink party cap and Halloween half-mask were still in place.

Suddenly Jerry was on the screen dedicating the all-star show to “my one boy audience.” Francis drew a sharp breath. It was true. As the show unfolded—directly to and for him, his excitement was almost too much to watch. For the first time in his nine years, he was really somebody, he really counted.

He grabbed the arms of his wheel chair tight with excitement and as Dinah Shore came on and sang “Davy Crockett,” he clapped his hands and hugged them tight. For the next hour and a half the greats of show business sang directly, right off the TV screen, to a little boy who the day before didn’t think he had a friend.

One by one they came out; Mary Costa, Eddie Cantor, Pinky Lee, the Mouseketeers, Eddie Fisher, Tennessee Ernie Ford, George Gobel, Jim Arness, Hugh O’Brian, Jerry Lewis and his son.

And when at the end, everyone joined in both on the screen and in the hospital with “Happy Birthday to You,” Francis’ pale little face was transformed with such a look of glowing happiness that, for an instant, Mrs. Reynolds was possessed of the wild hope that he would live, that this was not just the most memorable event of a too-short life.

As the image on the screen faded away, Francis X sat quite still. For the first time in his life he felt the fierce desire to live. To get well. Somebody cared.

This all happened more than a year ago, on October 8th, 1957.

Miraculously, as this is being written, Francis X is still alive. As Dr. Jellinek said, “Before the party, Francis couldn’t respond, he didn’t respond. And suddenly, he had the will to live.”

This year Little Boy Blue had a very simple birthday. A few cards, some presents from people in the immediate vicinity of the sanitorium, and, of course, something from Jerry Lewis and his son Gary.

Nobody knows how many more birthdays there will be. They can but wait . . . and hope . . .

Yet for one magical afternoon, Little Boy Blue was like every other little boy in the world, only more so. He was remembered, he was loved. And that love has sustained him ever since, and God willing, will do so a little longer.

THE END

WATCH FOR JERRY ON “THE JERRY LEWIS SHOW.” WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 10TH AT 9 P.M. E.S.T. ON NBC-TV. HE ALSO APPEARS IN PARAMOUNT’S “THE GEISHA BOY.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1959