Heritage Of Love

Under ordinary circumstances, one would expect to find a young movie actor in Hollywood, making—or waiting for the chance to make—movies. As in most phases of life, however, there’s always an exception to the rule. In this case the exception is nineteen-year-old James MacArthur, who makes his screen debut in RKO’s “The Young Stranger.”

Nowadays, Jim is to be found in Boston—on or near the Harvard campus, to be exact, where he is a freshman. If you’re in the vicinity, you’re apt to catch him hurrying across the quad to a history class . . . or tinkering with his Thunderbird (his high-school graduation present, which periodically acts up, much to Jim’s annoyance) . . . or lounging in one of the two big easy chairs he and his roommate acquired secondhand . . . or munching on a snack from the icebox they acquired the same way . . . or deep in a beer-and-bull session with the boys.

In many ways, Jim is just what you expect a college freshman to be. He has natural, boy-down-the-street good looks. His steady eyes are clear blue, his skin glows with health, and his sandy hair is so crisply crew-cut that only a suspicion of a curl remains. He stands about five-feet-six and has the trim, lithe build of an athlete. He is the kind of fellow any girl would love to date and any guy would like to pal around with.

We’d be the first to agree that Harvard seems about the most incongruous place for a rising young actor to be. But Jim MacArthur would disagree pointedly, and he has his reasons, all of which makes sense. They also make you realize that Jim is an extremely levelheaded, farsighted young man.

“I can take my time with my career,” says Jim, with all due modesty. Besides, he’s not sure that he wants to be an actor—although he greatly enjoys acting—and either way he is determined to get a well-rounded education as part of his preparation. “The most important thing for an actor is versatility,” he feels. He believes that experiences are “like building a pyramid”—the more you add and the higher you get, the closer you come to your goal.

According to Jim, “Harvard’s great,” and he seems to relish particularly the fact that there are no restrictive rules. He is also pleased to have met many different types of young men at Harvard. “I’m pretty adaptable,” he grins, leaving it unsaid that he gets along fine with almost anyone.

Although Jim is putting college before career, don’t think that you won’t be seeing him for the next four years. On the contrary. He is under contract to RKO to make a picture during each of his next three summer vacations. In addition, he has been approached frequently to work on television and plans to accept roles during vacation times, provided they do not interfere with his studies.

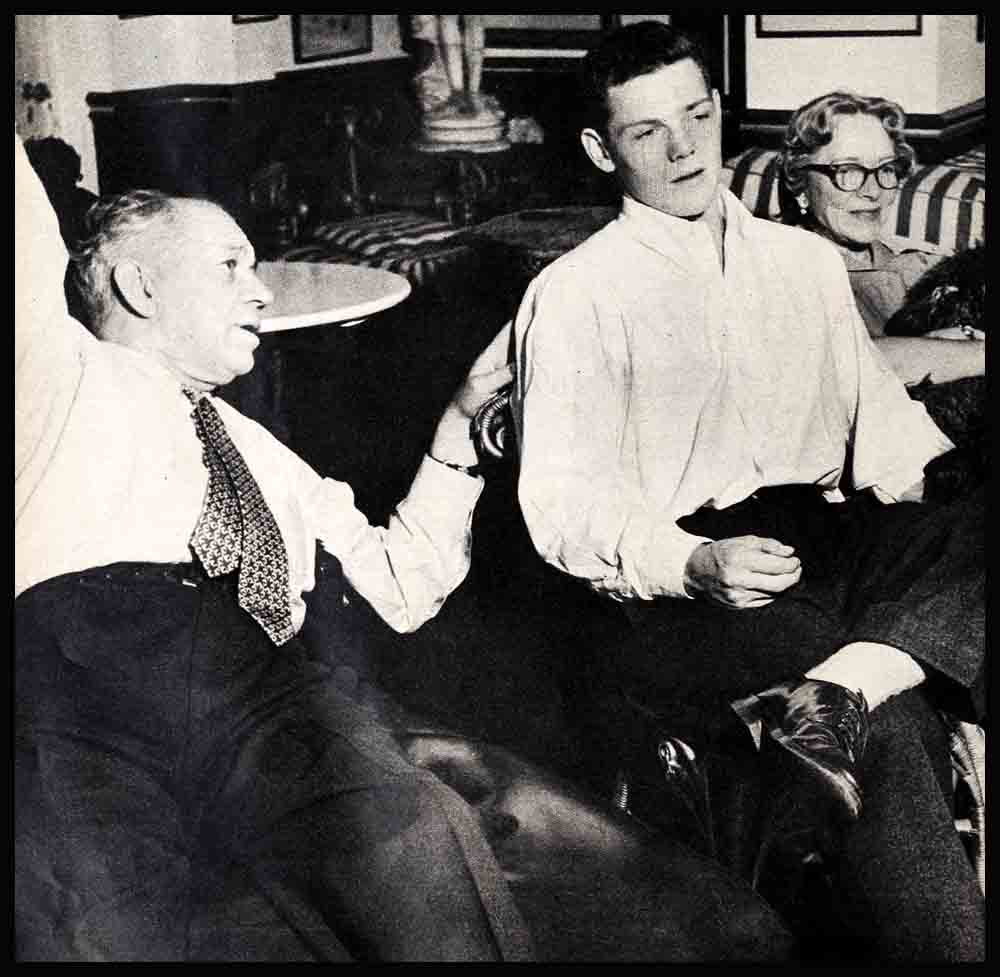

Being in the limelight is not exactly a new experience for Jim. Indirectly, he has been there most of his life, as the son of the late Charles MacArthur, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and ace reporter, and of the first lady of the American theatre, Helen Hayes.

Jim first bounced into the acting spotlight in the spring of 1955, when he made his TV debut in “Strike a Blow” on Climax! His performance prompted raves from critics and viewers alike and led to his contract with RKO. Since making “The Young Stranger,” he has been hailed in show-business circles as a real “comer.” Talent-wise, he has again proved to be an exception, displaying a veteran’s ability.

“The Young Stranger” is the film version of the award-winning “Strike a Blow.” In both, Jim portrays the central figure—a young boy who has to fight for his rights and who wants to be judged for what he is, rather than for what someone has said about him.

This desire to be judged on his own merits is also a vital part of Jim’s makeup, and thus far it has had rewarding results. Kim Hunter, who portrays Jim’s mother in “Stranger,” says of him: “It’s amazing that a youngster with no formal training can have such a sure-footed knowledge of acting. Heritage is a wonderful thing.”

His heritage, indeed, has played a big part in Jim’s life and work so far. The main part of it has been a warm, encompassing sense of being loved, with the perhaps special love which goes to an adopted son. Then there is the intensely theatrical background with which he was always surrounded. But equally important have been a strong common sense and a willingness to stand on his own two feet, the seeds of which were planted early in Jim’s childhood. These qualities have enabled him, among other things, to look upon his notable background with an appreciative as well as realistic eye. Consequently, Jim regards his famed name as both a glowing asset and a heavy responsibility. While he is grateful that it has brought him opportunities other young men must struggle to find, he has also learned to count its cost. “It’s tough, sometimes,” he says, “to have everything I do associated with them, but I still think my folks have been the greatest.” His reasons for saying this are legion.

Growing up in Nyack, New York, Jim lived in an atmosphere of mutual love and respect. In spite of his parents’ notoriety and the many celebrities who constantly visited the rambling Victorian home of the MacArthurs, Jim was allowed to develop normally and to partake in all the usual boyhood activities. He was never rigidly disciplined, nor did he get into any major mischief. “Sure, there were times when my folks didn’t want me to do certain things,” he shrugs, “but they never absolutely forbade me. And, besides,” he grins, obviously thinking of the times he did act against their wishes, “they were always right.”

Jim recalls being the recipient of a spanking only once, “when I was about four or five. I crawled out on the roof outside my father’s room, and when he told me to come back in, I just laughed and kept going. So my father came out after me, hauled me in and paddled me with a hairbrush.” He adds thoughtfully, “I think a talking-to is more effective, myself.”

There was always plenty of good talk in the MacArthur household, for the whole family loved to get into what Jim calls “hot discussions,” even though “my father always won the arguments.” How come? “Well, we’d be arguing along, then my father would use about five big words in a row that I didn’t know and I’d have to go look them up in the dictionary. By that time,” he grins, “the discussion had sort of disssolved.”

Charles MacArthur was an intensely brilliant man who was also noted for speaking his mind. Jim was keenly aware of his father’s strong personality and, although their relationship was not of the typical father-son type, Jim has his share of fond memories. Oddly enough, in relating them he never refers to “Dad,” bu’ always to “my father.”

“We never went on fishing trips together, or things like that,” he says, “bu then neither of us liked to fish, anyway Actually, just going someplace with my father was exciting to me. And when I was away at school he’d call me up once a week and tell me about everything that was going on.”

Jim also recalls that often, when he was little, his father would approach him fists raised, ready to box. The first few times this happened, Jim just stared back at him. Then his father would say, “You’re not ready yet.” Later, when Jim began to catch on, they would have sparring bouts “My father would always look at your feet, and keep looking at them. It was very distracting,” he says, as if still a little confused. “Then before I could do much,” he adds rather sheepishly, “he’d step on my foot and I’d lose my balance.”

Many times, Jim remembers, when he had come into a room where his father happened to be, Charles MacArthur would look up at his son and say, out of the blue, “Whatever you do, don’t become an actor.” Nor was Helen Hayes anxious to push Jim in the direction of dramatics. She didn’t try to discourage him from becoming an actor, but she did insist upon his being educated in normal fashion “That’s why she didn’t send me to the Professional Children’s School,” says Jim “and I’m glad she didn’t.” Instead, he attended Solebury School in New Hope. Pennsylvania, where he starred in basketball, football and baseball.

If, after college, Jim decides that acting is still for him, he then plans to take dramatic courses. This his mother has strongly advised. Always in their close mother-son relationship, Helen Hayes has done a great deal toward giving Jim a sound Outlook and constructive advice. She was also inadvertently responsible for such dramatic training as he has received. “When my mother was getting ready for a play,” Jim recalls, “I would hold the script and read the other people’s parts to help her learn her lines. I suppose,” he adds, “some of her way of doing a role has sort of rubbed off on me.”

Some of the actual atmosphere of the theatre also rubbed off on Jim. Several summers ago, during a Helen Hayes festival at the Falmouth Playhouse on Cape Cod, Jim had a few walk-on parts. He also helped the theatre electrician and, in fact, grew so interested that he begged to be allowed to stay on after Miss Hayes’ plays had ended. As a result, he lighted the show for Barbara Bel Geddes in “The Hut” and for Gloria Vanderbilt in “The Swan.” Recalling this, Miss Hayes says with a fond motherly chuckle, “I’m sure the stars would have died had they known there was only a sixteen-year-old boy on the lights!”

Two summers ago, Jim again had the privilege of working with his mother when she headed the company that presented “The Skin of Our Teeth” in Paris. Miss Hayes has long been noted for getting stage-fright before every performance. Jim confirms this fact, saying, “She’s always a bundle of nerves before going on, and it’s always bedlam backstage.”

Although Jim was allowed to absorb a great deal of theatre atmosphere, both his parents refused to let him be exploited throughout his early years. They continually rejected suggestions for a play for Jim—until the script of “Strike a Blow” was submitted. This one pleased them, and they gave the go-ahead signal that was to launch Jim as an actor in his own right.

Jim has also had his share of the jitters, though “more on the stage and TV than in movies,” he explains. “But once I get into it, I’m not nervous.” Jim found his biggest problem in making his first movie last summer was the confusion and noise on the set. At first he thought the crewmen were a bored, uninterested lot, but before long he changed his mind. “They’re a swell bunch of guys,” he says now. He especially enjoyed playing cards with them, “although I lost about half my salary at it!”

Jim has also been initiated into another phase of Hollywood life—gossip. One morning he was greeted by a newspaper item stating that he was engaged to Joyce Bulifant, his high-school sweetheart. The statement happened to be untrue. He sought advice as to what to do about it, and was advised by his agent to “Just let it go.” But, even after he had returned East and was registering at Harvard, the gossipy tongues were still wagging. Waiting for Jim on registration day was a letter from his mother, who was in Hollywood, stating with concern that she had heard, not from one, but from four or five sources, that he was engaged to a young girl out there. It wasn’t that she is against his getting married, Jim explains, “But she doesn’t want to hear about it secondhand. So,” he adds, “I called her—collect, of course—and told her it was ridiculous.”

While on the subject of marriage, Jim says, “I’ve thought a lot about marriage—not to someone in particular, but just marriage in general—and I don’t want to marry yet. There’s still plenty of time.”

Jim has also thought a lot about acting—in general and in particular—and, as he does on any subject, States his feelings unhesitatingly. Also with a perceptive and practical attitude that is seldom found in one so young. “I just have to do what comes naturally,” he says. “I don’t believe I could ever follow that method they use at the Actors’ Studio, where they analyze every little thing about a character. That’s wonderful for some people, but it doesn’t work for me.”

Although he is keenly aware of his distinguished background and the advantages it has presented him, he has never been blinded by it, nor has he capitalized on it to any real extent. However, he admits, “I don’t feel I have to go through the starving-actor routine. It’s all right for those who want to or need to do it, but I’m lucky. I don’t have to.” And, no matter what career he chooses, Jim says, with the determined confidence of youth, “I want to be master of what I do. I don’t ever want to feel I’m a slave to anyone.” Which again clearly reflects the sense of independence his parents instilled in him.

Although Jim insists that he has not decided on an acting career, his thoughts and actions certainly show he is headed in that direction. But no one, including Jim, can predict what will happen after he fulfills his contract with RKO and after he graduates from Harvard. At this point, his life is like a road map—there are many routes leading to one destination or another, and they are all clearly indicated. It is up to the driver to choose which one he will take.

There is no doubt that Jim MacArthur is a competent driver who has his sights firmly set on the road ahead. Whether he will take a super-highway or a short cut is still up to him, but either way he is prepared for any detours or delays. His abilities have already been tested and not found wanting; from all indications, his destination should certainly be reached in the esteemed and enviable manner of his world-famous parents, Helen Hay es and Charles MacArthur.

THE END

Go see: James MacArthur in “The Young Stranger.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957

No Comments