The Devil Is A Gentleman—Marlon Brando

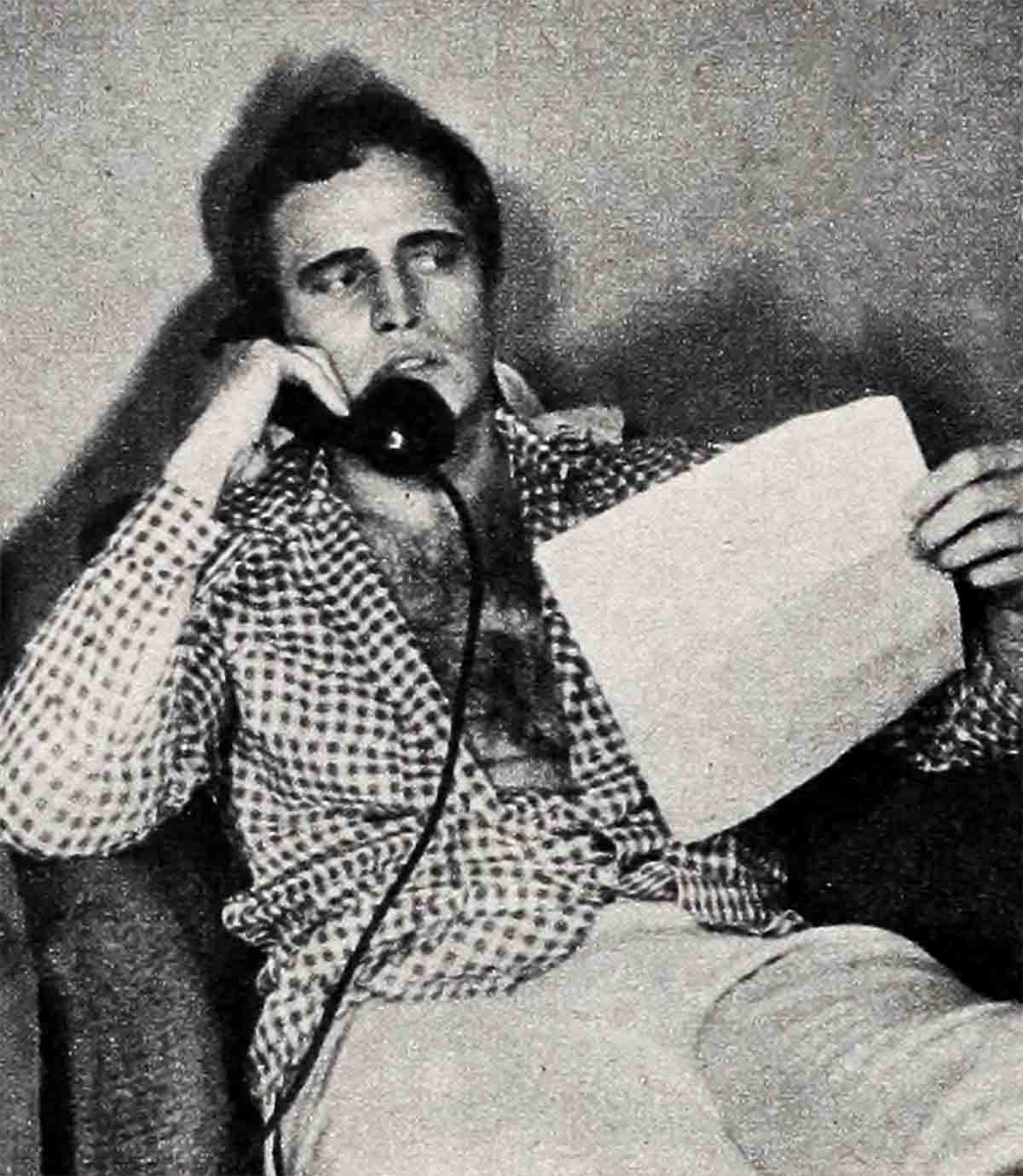

Marlon Brando spoke into the telephone with intensity, but hardly above a whisper.

“But I know something is wrong with the line,” he said earnestly. The grin spreading over his face he did not let reflect in his voice. “Operator, please check again.”

On the other end of the line Charlotte Austin, pretty little 20th Century-Fox actress, picked up the telephone and heard the operator saying, “It seems all right to me.”

“What,” demanded Charlotte, “is going on here?”

“Just checking the line,” the operator said, and there was a click as she went off the line.

Then Charlotte heard Marlon’s voice, deep and resonant, saying, “Charlotte? Just called to see if you are ready. Can I come over to see you now?”

“I’m ready,” Charlotte assured him, glancing at her watch with more than a little irritation—Marlon was already ten minutes late. “Hang on a minute,” Marlon said. “It’s noisy in here. I want to shut the door.”

Charlotte waited impatiently, holding the telephone in her hand. Suddenly, she felt as if someone else were in the room, a sort of eerie, skin-creeping sensation came over her, and she could feel her mouth go a little dry. She hesitated to turn around, but with the phone in her hand, she gathered her courage. She swung around rapidly and screamed . . . a rousing scream which people only let out when they are scared out of their wits. There stood a man. But as suddenly as Charlotte started screaming, she stopped and went into gales of laughter. The man was Marlon Brando. A sheepish, grinning Marlon.

Marlon had entered Charlotte’s house through the open kitchen door, and spotting the extension telephone in the kitchen, had picked up the phone and asked the operator to ring it to check it. In the living room, Charlotte heard it ring and answered it as Marlon had anticipated. This just illustrates one of a hundred playful, human, interesting, sometimes touching, sometimes whacky things that can happen when Marlon Brando is your friend.

This same predilection for doing the un-expected showed up dramatically when Brando announced his engagement to Josiane Berenger. He had met the pretty young French model six months before in New York and is reported to have asked her to marry him within hours after their meeting. She subsequently visited California during the shooting of “Desiree” but was carefully shielded from reporters and photographers by Brando. She therefore remained a mystery figure in the actor’s life—noted by the alert columnists but without detail of their relationship.

It was not until late October that the news of Brando’s official engagement burst like a bombshell on the small Riviera town of Bandol, France, where the engaged pair filed official notice of their intention to wed. At the appearance of a battery of newspapermen and photographers, Brando showed every sign of panic—rushed his girl off on a sailboat ride to escape the mob. Later he yielded to demands for an interview, and said, “She is the only girl I ever wanted to marry.” With their hopes for peace and quiet shattered by the press furor, Brando left the Berenger home and headed for Rome. His fiancee fled in the opposite direction, heading for Paris, then New York by air, with the understanding that the two would meet in New York. Arranging her U. S. visa in Paris, Josiane exclaimed, “I don’t want to be a Hollywood housewife. I want to study dramatics in New York.”

As in the romance of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, no wedding date has been announced as we go to press. In both cases, the motive is privacy. But for such charming and colorful young people as these, such a course is difficult in the extreme—as those who know Brando well can easily testify.

His friends, some new, some dating back to his early days in dramatic school, weave word pictures, ever-varying, ever-colorful of the man who has become one of the motion pictures’ finest actors. For instance, there is the Saturday that Johnnie Ray was feeling low and lonely. It was one of those times when the California sunshine was an irritant, draining a man of energy instead of invigorating him. Johnnie headed for Ocean Park, the Los Angeles equivalent of Coney Island, where he could buy a ticket on the roller coaster and at least feel the wind in his face. Blind to everything but his own woes, Johnnie climbed into his seat. Then, behind him he heard a shout, “Hi, man, what gives?”

Johnnie looked around into the impish dark eyes of Brando. Johnnie had to answer the grin on Brando’s face. One ride on the roller coaster, then Johnnie joined Brando and Sam and the rest of the gang for a go at everything from pitching baseballs at cardboard milk bottles to feeding lighted cigarettes to the fire-eating man.

But you don’t have to be a famous singer like Johnnie Ray to enjoy Brando’s company. You can be a stevedore like Joseph Conepo who worked in the “gang” in New Jersey where “On the Waterfront” was filmed.

“Have you ever seen how good Brando is with kids? Like all the other youngsters, my boy Joe, Jr., came down so we could take a picture of him with Brando. Then Joe got bashful. Marlon understood, but more than that he knew how to handle Joe. He let Joe stand around for a while till he got used to everything, and then walked over to him and asked if Joe wouldn’t have his picture taken with him. Little Joe had a whale of a fine time.”

While making “On the Waterfront,” the stevedores picture him as being a “regular guy” and in Hollywood, on the set of “Desiree,” there was the same feeling. Between takes, he played chess or kicked around a football with his stand-in, Darren Dublin, another pal from Dramatic Workshop days. And he was downright frisky with Dublin’s five-year-old daughter, Heidi. One day Heidi came on the set with her toy sword, and Marlon picked up a coat hanger and teased her through a mock duel which he climaxed by clutching his side and pretending to fall down dead. Dignity, cast and clothes be hanged!

His lack of concern with “what will the neighbors think?” is an attitude which stems from way back when. . . . Harry Belafonte and Brando knew one another during this period. Eight years and two success stories later, they’re still close friends. They met at the Workshop where Marlon was an advanced student, already appearing on Broadway in “Truckline Cafe.” Harry was a beginner.

“I was one of the very few Negro students in the school,” Harry says. “And Marlon was one of the first students to befriend me.”

“Most of us had little money in those days,” Harry continues. “Sometimes the theatres helped out by giving the girls usherette jobs, letting the guys work the concessions. One way we were able to take in everything playing on Broadway was to ay our money and buy one theatre ticket. Maybe I’d see the first half of the play and then Marlon would take over after intermission. Sometimes it was the other way around. Afterwards we’d go to the local cafe where they’d let us sit over a nickel cup of coffee (we could usually afford a cup apiece) and compare notes, each of us catching up with the action the other had missed.”

Marlon and Harry also dreamed up a bit of mischief together. In school there was an actor who was having great visions of success. He liked to give the impression, both in school and out, that his dreams had already come true . . . he belonged to the theatah and, this being the case, the theatah was extremely fortunate.

As in almost every drama school, the workshop classes rotated in assignments, one week Marlon and Harry might be supporting players, another week star performers, another week the fellows who cleaned up the stage. For this particular week, Marlon and Harry were appointed members of the backstage crew and the “theatah fellow” was the star of the show. Sir Thespian busied himself thinking up unexciting and rather unnecessary chores and assigning them to the pair.

The day arrived when the workshop group was staging “Twelfth Night,” and Sir Thespian was required to wear a padded stomach for the role. In the belief that all work and no play makes for very dull boys, Brando and Belafonte got hold of some itching powder and lined the padding with it.

So on this warm summer evening, underneath the hot stage lights, Sir Thespian made his entrance. Immediately he became a pretty miserable man. Unable to scratch through the thickness of the padding, he managed to squirm through his role and come off roaring.

Next day a conference was held to find the culprits. However, to the delight of the entire student body, they were never discovered—until now.

School days over with, Marlon went on the road with the Katherine Cornell show and Harry went into night clubs. They kept track of each other haphazardly, with Marlon dropping into the club where Belafonte might be singing or Harry going back stage if he happened to be in the same town when Marlon was on the road. Belafonte tried pop singing and found it unrewarding and turned to folk singing. With a writer and another actor, he opened a restaurant in Greenwich Village. Marlon was a frequent visitor—and Harry was always delighted to see his old friend and not just for friendship’s sake.

“He’d always head for the kitchen so we could have a talk,” Harry says. “To my delight, while we talked, he’d start doing the dishes and if I could keep him talking long enough, my kitchen would be clean by the time we finished.”

There were frequent reunions when Harry and Wally Cox were appearing at the Blue Angel. Wally and Marlon were going through their motorcycle stage—both thought motorcycles were the greatest, but not Harry! Harry didn’t like to think about them at all. After repeated urgings, Harry succumbed to a couple of rides. “I finally came to the conclusion that if we were ever to dissolve our friendship, this was the time.”

Brando’s and Belafonte’s professional paths have crossed numerous times. When Harry came to Hollywood to appear in “Bright Road” for M-G-M, Marlon was at the studio making “Julius Caesar.” “He was the only person I knew in Hollywood,” says Belafonte. “And it was as it had been when I was a newcomer in school. He looked me up on my first day on the lot and it was like old home week.” Harry was booked into the Mocambo while Marlon was in Hollywood shooting “The Wild One,” and they met again when Harry returned to California to appear in “Carmen Jones.” Marlon was making “Desiree” at the time.

It was during this last period that Harry and Marlon stopped by a jazz club one Saturday night and spent the entire evening listening to the music. Since they wouldn’t be working the next day, when the club closed, they asked some of the musicians if they happened to know of a jam session where the local bandsmen might be gathering for an after-hours musical spree. The musicians gave Marlon the name of a place, and Brando and Belafonte arrived to discover that there would be no music that night. The musicians were heading home.

“No point in waiting around,” said Marlon. “Let’s go.”

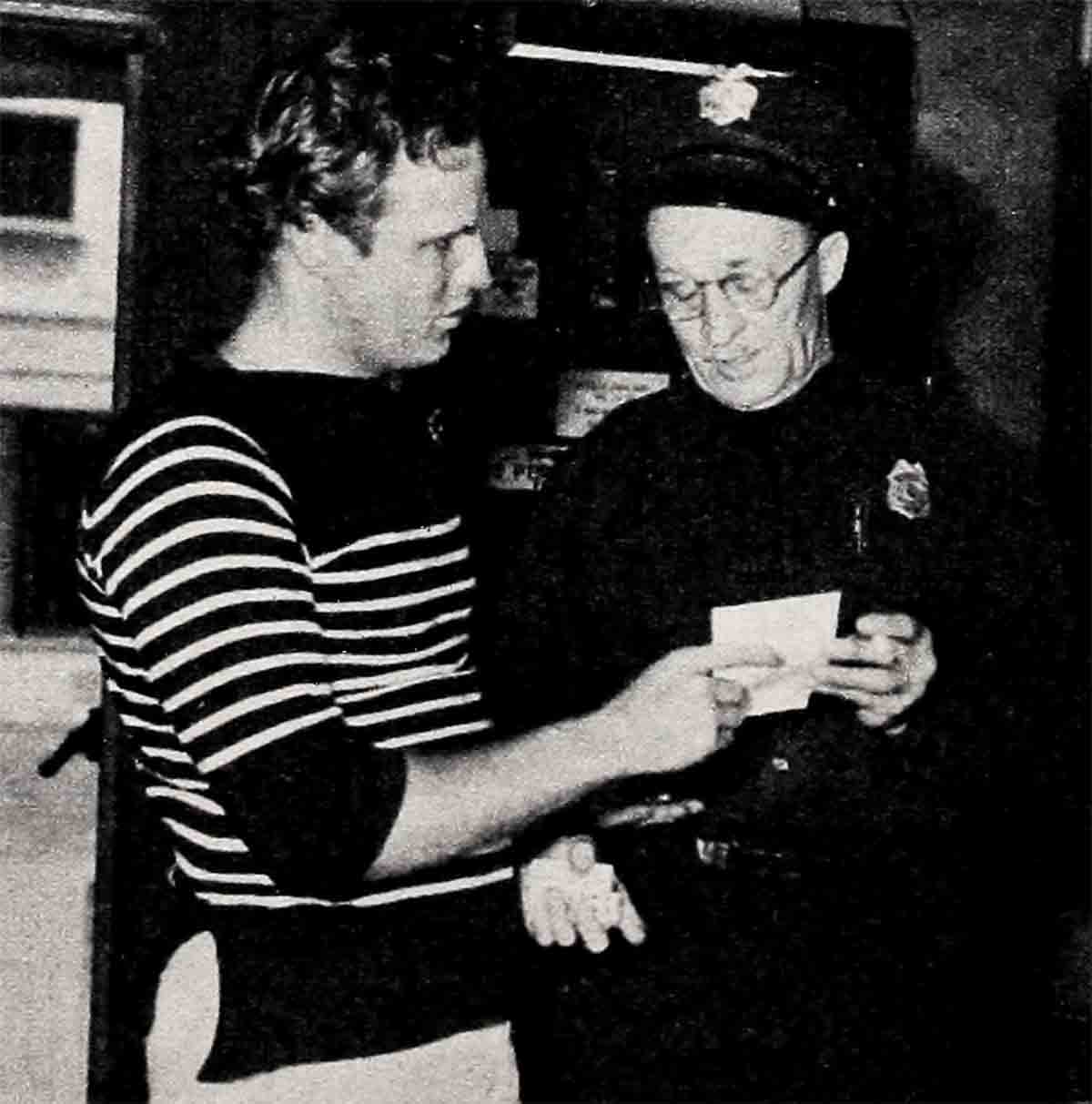

As they reached the door, however, a man in a blue business suit appeared and stretched his arm across the exit. “You don’t really want to leave now, do you?” he asked pleasantly enough.

The place was being raided.

However, when the police discovered no liquor was being sold, they departed quietly, leaving Brando and Belafonte breathing a sigh of relief. Brando especially didn’t need any more crazy publicity. Incidentally, in spite of Brando’s interest in jazz and bongo drums which he plays exceedingly well, Marlon neither smokes nor drinks. On his really “wild nights,” he might indulge in a ginger ale—but then not more than one glass.

Much has been made of Brando’s sensitivity to the publicity he received when he first came to Hollywood and his insistence that he be pictured only as the serious artist he is on stage or screen. The fact remains that in Hollywood or outside it, standing on one’s head in a commissary (as Brando once did), answering a newspaper person’s questions in French (as Brando once did) is real gone behavior. Belafonte claims that Brando is a tremendously sensitive guy and that his unconventional behavior is no deliberate disorder designed to make him a colorful motion picture star. Take Russell, the raccoon. Reams of stories were told about Marlon having Russell as a pet. According to Belafonte, maybe movie stars don’t have raccoons for pets but a lot of other people do. They make darn good pets. More than this, at one time Marlon was extremely interested in zoology and used to spend days at the Central Park and Bronx zoos. During this period, Marlon bought Russell and became very fond of him as a pet. However there was so much comment that Marlon finally gave him up.

Brando has always believed in doing things the way he wants to do them—the way he can believe in doing them. For instance, at one time he was very friendly with an artist whose works were being displayed in one of the New York galleries. Despite this sign of success the artist was flat broke, so Marlon’s pals came to help out with a collection they were taking up for him. Brando was a success in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” and his friends were shocked when he refused. No one could understand why. They argued that he liked the painter, that the artist would repay the loan as soon as he could. Brando wouldn’t budge and his friends told him off in no uncertain terms.

One day soon after, the incident glossed over, Brando’s usual gang was up at his apartment and there, on the walls of the apartment, were his artist friend’s paintings—$1000 worth.

Brando felt that the worst thing he could have done would have been to lend money to his friend, when what he really needed for a boost in his morale was a few sales.

“That’s what kind of a guy he is,” Belafonte says, “that’s the way he thinks.”

Both Marlon and Harry belong to the same “school” of artistic thought. Both believe in calling upon life itself for authenticity. Brando has learned much from living and he enjoys doing things he’s always done—he won’t let Hollywood or anything else keep him from continuing to enjoy these things—even at the risk of being considered “not with it.”

There’s an old saying, “If you want to know me, come live with me.” Brando, signed for the role in “Viva Zapata,” went to Mexico to live for a month. Signed for “On the Waterfront,” he went to work with longshoremen. He wants to project the identity of the person he is portraying . . . hand his public a real slice of life. He forces his audiences to think and to listen . . . and to forget the big bag of popcorn.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955

No Comments