Wanted: A Man!—Kathryn Grayson

There is an idea in some quarters that Kathryn Grayson, however eminent and undeniable her status as a star, does not, away from the soundtrack, produce the sort of chitchat that sends the troops storming into battle without their Vitamin C.

While Miss Moore, for example, dwells on the virtues of donning ermine bathing suits and. Mrs. Di Maggio on those of staying clear of undergarments, Miss Grayson is wont to ponder how tough it is for a girl to shift from second into high in the middle of “The Bell Song.”

Miss Hayward and Mr. Chandler are maybe thisaway, Ava and Frankie that—Miss Grayson is positively at home with a good book and a very, very good five-year-old daughter named Patti Kate.

This is the stuff that soups up circulation and stands the beauty parlor on its collective ear? No. Not this year.

“It’s a shame,” said Miss Grayson not long ago, “but it’s sort of late to back down. My life and my career have been—what were the words you used? Dignified? Decorous? And just a little dull. Well, I can’t apologize for it. I’ve wanted it that way. But have you ever found me dishonest or evasive in an interview? I’ve always answered what was asked me, provided it’s in reasonable taste. I—I don’t feel stuffy. I don’t want to be stuffy.”

Miss Grayson is always forthright, amusing and even, at the right times, earthy. She has one long-standing restriction—an intelligent one. She will not hold still for an interview if the story promises to be poisonous or saccharine.

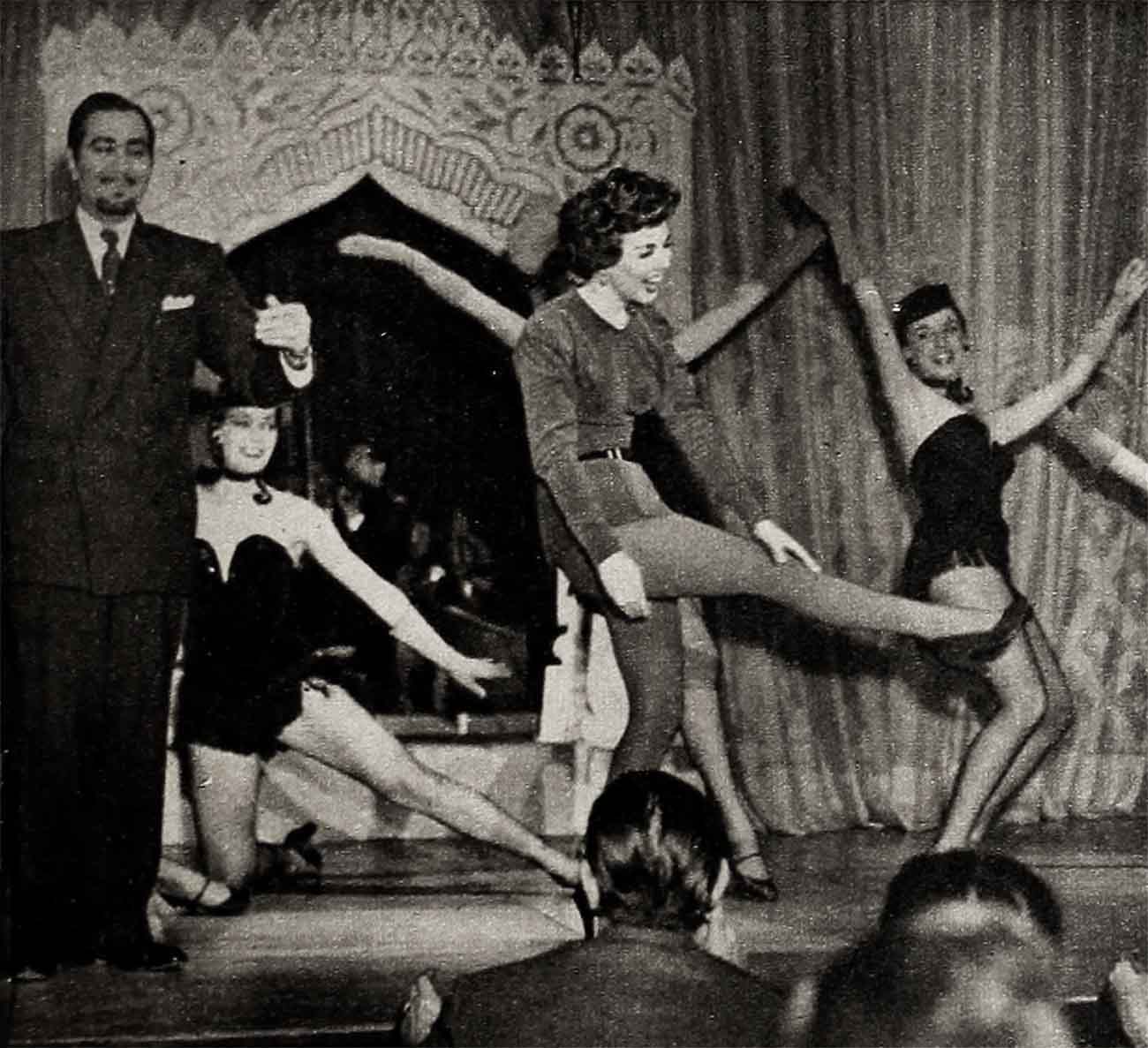

Now the scene was Las Vegas’ posh Sahara Hotel, where Miss Grayson was playing the first nightclub engagement of her life. Playing it very nicely, too. Putting out with mostly operatic arias and making the florid Vegas clientele like it. She was also breaking house records, although no columnist nor trade paper had said a word about it. She had followed Donald O’Connor in. Before him had been Marlene Dietrich, whose costume had given the sensational illusion of being transparent above the waist. Well, Miss Grayson had got some vicarious publicity out of that. She’d gone up to Vegas to case the joint, so to speak, before she opened, and had sat in on one of Miss Dietrich’s performances wearing what she, Miss G., now describes as a moderate evening gown, and Miss Dietrich was said to have cracked a bit wise about it. One of the columns reported it.

“And after I’d complimented her on her show!” said Miss Grayson. So a couple of nights after she opened, Miss Grayson, who is an accomplished mimic and dialectician and perhaps should have been given a try at straight comedy long ago, stepped out of her routine. In a fine Teuton accent, she made noises so exactly like those of the throaty Miss Dietrich that she brought the house down. The edge was hers. Miss Grayson can imitate Miss Dietrich fine. Miss Dietrich, for sure, can’t imitate Miss Grayson at all.

But with Miss D.’s departure, Miss G. was still getting competition from the throaty set. As she opened at the Sahara, the Sands, a mile or so up the road, unveiled Tallulah Bankhead. Miss Bankhead, as boomingly uninhibited as Miss Grayson is restrained, sprayed the air with dahlings, regaled the hypnotized press in basso profundo, and finally asked a harried reporter who had just left Grayson: “But tell me one thing, dahling! Why did you see a stahlet before you came here to see a stah?”

To have implied to Miss Bankhead that Miss Grayson’s billing and take-home pay were at least the equal of her own would have been to invite carnage, so no one did. Miss Bankhead got the headlines, as had Miss Dietrich before her, and what did Miss Grayson get? Just a little old $90,000 for three weeks’ work, it says here.

“I’m not the headline type,” said Miss G., “and I honestly don’t care. I’ve planned it that way, the way I plan everything. And I’m as happy as I can be. I’ve made my separate peace with everyone and everything, and those who say I’m not happy or that I’m lonely in my ‘big, dark, gloomy house,’ you tell them something for me. You say I’m happier than any of them. I’m the happiest.”

It was early evening and cold and rainy in Las Vegas, which is most unusual. Miss Grayson was a little ill, with subnormal temperature and under a physician’s care. She may have been more tired; for four years now, doctors have been trying to get her away from everything for a complete rest. ‘Everything’ includes Patti Kate, who is the strenuous type and Miss Grayson is not going anywhere without Patti Kate.

Miss G. wears no make-up except lipstick and something around the eyes, with the result that she tends to glitter a trifle, like a casually wiped winder. She didn’t look tired and she didn’t look ill. She looked great. But she had been sleeping a great deal and she sat somewhat slumped in a deep sofa and didn’t move about much. Patti Kate did the moving. After a while someone came and took Patti Kate away for one of her excursions about the hotel. “What time do you want her back?” he asked.

“About Tuesday,” said Miss G. A jest.

Patti Kate went, and Miss Grayson stirred faintly. She’s a small girl with close-cut auburn hair, and the widely known heart-shaped face and snub nose. She didn’t feel a lot like working but she was going to work.

“I want you to see my ‘big, dark, gloomy house’ sometime, so you’ll know what they’re talking about. It’s a wonderful house—to sing in, to work in or live in. It’s got bookshelves with books in them, and the books have been read. Isn’t that horrible? And the grounds in the back slope down toward the Riviera golf course and there’s a lot of space, so Patti Kate has room to play. It’s fenced in just the way you’ve heard. But they just say, ‘Oh, it’s all fenced in,’ without knowing why. It’s not only for my own privacy but for Patti Kate’s. There are a lot of drunks around the golf course—not the members, of course, but others who wander onto it. Therefore, the fence. It’s very simple to me. I don’t see why it should bother other people. I’m thinking of my child.”

Patti Kate’s father, who is Miss Grayson’s divorced second husband, Johnny Johnston, had been up to see her a few days before.

“I outgrew him,” said Miss Grayson. “That’s my side of it. There are two sides to everything—and isn’t that a bright observation, considering my weakened condition? Johnny’s a child. I think he’ll always be a child. Johnny needed desperately to be loved but—I think not the kind of love that can be given indefinitely. You have to understand his background, though. Johnny and I are good friends. I’ll always feel that way about him. But toward the end of our marriage—you remember?”

Toward the end of the Johnstons’ marriage, there was some sort of mishmosh involving reported attentions of Johnston to Shirley Temple, Miss Grayson’s subsequent wrath, and the attempt of a close friend and neighbor, Joe Kirkwood, Jr., to intervene. Kirkwood, a professional golfer and film portrayer of Joe Palooka, evidently was in the middle. He was quoted in the first stage of the disruption as wishing broken bones to Miss Grayson—purely a figure of speech. Later, he and Johnston got into fisticuffs at the Riviera bar. Very complicated. Anyway—

“Toward the end of our marriage,” Miss Grayson resumed, “I could carom a cold cream jar off Johnny and catch Joe Kirkwood with the ricochet.”

Prior to Johnston, Miss Grayson had been wed to another actor, John Shelton. That one had turned sourish, too. What now?

Miss Grayson took a long breath. It is one of Miss Grayson’s modest prides that her chest expansion is three-quarters of an inch greater than that of Joe Louis, whose chest expansion is a dandy.

“I will think,” she said on the exhale, “a long, long time before I marry again. And when I do, it’ll be a man who can stand on his own feet, make his own living, be an adult from the ground up. I’m not sure I want any more actors and I’m not sure I want any more charmers and I’m absolutely sure I don’t want any more children. That is, I want children but I want to have them in the normal way, not marry them.

“I keep reading I’m going to marry a man in San Francisco. But I’m not. At least, no one I know of now. I have a good friend there; he’s my brother’s friend, too. He’s a wonderful guy. He’s asked me to marry him. I’m afraid he didn’t make out very well. He was down here last week. I had to suggest he go back home. I was working and—well, you know.

“But if I could find a man, the kind I’ve described, someone who’d stand up to the world and stand up to me—”

She wished to be dominated? Some sort of ruthless egotist might fit the bill.

She laughed. “No, I’m not sure there’s a man alive who could dominate me. But I want it on an equal footing. I want to look up to him and have him lock up to me. Stand up to me and let me stand up to him. That kind of scratches the ruthless egotist department, doesn’t it? I guess a girl could get really bruised with one of those, not to mention really unhappy. No, that I couldn’t take.”

There was a ruthless egotist of a sort pursuing Miss G. a while back. He was a hot-blooded deal, a chap from out of town. He would call Miss G. at two in the morning and wonder how she could stand it away from him. Unhappily, he had accumulated, since the days Miss Grayson had genuinely liked him, a set of atrocious manners. She never liked him beyond liking, you understand, so now it became intolerable. “I wasn’t exactly swept off my feet,” she has conceded.

Miss Grayson brooded gently for a moment and then took on “them” again. “I wonder what they expect of me,” she said, apparently referring to the hungry segment of the public that will settle for nothing less than sidewalk brawls and bottle-smashing at Ciro’s. “Just because I don’t have a new love affair every week and I’m not seen around nightclubs, which I don’t happen to like, I don’t think I’m a bore and certainly I’m not perfect. I’ve even been out when perhaps a little elderberry wine had been mixed into the lemonade and I got the giggles. But what’s wrong with dignity and why should it be confused with stuffiness? I’m not stuffy. You know I’m not.”

Possibly the simple truth is that Kathryn Grayson is a very nice girl living in a professional climate where standards are sometimes sleazy. The barometer for conduct is a strange one: the garish are “colorful” and the well-behaved “dull.”

Miss Grayson has actually been scored for her selfless devotion to her family, some people in the industry having called her, not wholly in reverence, “The Little Mother Of All The World.”

“That’s almost the payoff,” said Miss G. “I love my family. We’re exceptionally close. My mother and father are both ill. But there’s enough to go around. That’s what matters. Whether I earn it, or mother or father or brother—and whose business is it, anyway?”

Patently it is no one’s business. It may equally be no one’s business that throughout her career, Miss Grayson has steadfastly refused to pose for cheesecake. She has said that she is “not the type.” Neither her long-time home studio, Metro Goldwyn-Mayer, nor Warners, to whom she now has a picture-a-year commitment, has been overjoyed by her stand in the matter, and one time, while with Metro, Miss Grayson found she was not overjoyed herself. This was after thousands of requests had come in from soldiers in Korea.

Miss G. called Metro and said to go ahead. The pictures were made, Miss Grayson looked them over—and killed every last one.

“I didn’t want to do it. But look: I have a thirty-nine-and-a-half-inch bust, then taper right down to a twenty-four-inch waist, then hips something like thirty-four. That’s—I don’t know—rather emphatic, wouldn’t you say? Frankly, I guess I’m embarrassed. After Kiss Me Kate, a woman wrote to me and said I should—uh—use restraint, and I think so, too. I’m a moderate, all right, and nothing can be done about it.”

Doubtless it is a good thing. The vast majority of Miss Grayson’s large following gets rattled when she kicks up her heels, and registers grief and disappointment. At Vegas, to break the semi-lofty plane of opera and ballad, she had a bit wherein she detached a voluminous skirt to reveal a tighter one, slit to the knee. It was a reprise on a dance number she’d done in a

picture called Two Sisters From Boston, a charming little change of pace, delighting the audience. But somebody reported that regal Katie was peeling right out in front of everybody. Peeling, yet! The first letter began: “You don’t have to do a striptease to sell yourself, you with all your God-given talent!” That, as television’s Mr. Peepers sighs from time to time, is the way she goes.

Kathryn Grayson was born in WinstonSalem, North Carolina and named Zelma Hedrick. When she was three, the family moved to St. Louis, and that she thinks of as home.

Miss Grayson was educated in St. Louis and got her professional start through the good offices of Frances Marshall, then a star of the Chicago Civic Opera. It was Miss Marshall who developed her voice, nurtured her assurance and gave her the flying start to what she is today.

Once in Hollywood, Kathryn was snapped up in a hurry—it was one of those no-test-is-necessary bits—by the astute Louis B. Mayer, and jumped into the top brackets in her third film. She’s been there since.

But whether or not she’s entirely happy there is problematical.

“I’m certainly not retiring,” she has said. “But there aren’t going to be any more of these cream-puff parts. No more meringue. I’ve had it. I’ve a wistful idea I might be able to act, and I’d like a chance to prove it. Some singing, yes, but incidental to the story. Did you see the picture in which I played Grace Moore? That was the best so far. I’d love another like it.”

And what did she plan next?

“Now, you mean? After I leave here? That long, long rest I’ve been hearing so much about. I’m going where nobody’ll know I’m going. There’s an element of risk about that, but the complete privacy is worth it. I’ll bet you a Vegas dollar right now that inside a week, they’ll have me secretly married or in a sanitarium getting over a breakdown or consulting an analyst in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Only one thing worse could happen—their not even bothering to guess.”

Not one of Miss Grayson’s biographies makes note of a calisthenic accomplishment she swears is hers. One-arm chinning—a feat essayed by Mr. Darryl Zanuck but not accomplished. Mr. Zanuck said at the time that only five men in the world could do it, and after he’d made his try, there were only four. Miss Grayson has news for Mr. Zanuck. She can do it.

“He was talking about men,” she said. “But I can do it. Honest. If there were a bar here, I’d show you. A chinning bar, you know.”

Her biographies do make such notes as: “she devotes considerable time to her garden” (just a so-so amount of time), “long and frequent walks” (more frequent than long), and “ten hours of sleep a night” (correct).

They say that she likes drawing and painting, horseback riding and golf (Babe Zaharias’ assorted titles are safe enough) and has a St. Bernard named Throckmorton.

Actually she had a St. Bernard named Throckmorton and a wonderful dog he was. But a few months ago, Throckmorton gamboled out onto San Vincente Boulevard near Kathryn’s Santa Monica home and was killed. It wasn’t the driver’s fault. And naturally it wasn’t Throckmorton’s, because dogs in the intrinsic nature of things are faultless. But the driver wept on Miss Grayson’s kitchen table, and who can blame him?

There’s nothing about how Miss G. has her hair done twice a week at the Brentwood Market in West Los Angeles and buys her gas from Union Oil and travels with an entourage of brothers and sisters and in-laws (and they are all very close) and an efficient secretary named Sally Norton, or about what a bright little girl Patti Kate is, with an I.Q. way, way up to here. When Patti Kate met Art Linkletter, the radio and TV man, in Vegas, she was most impressed and crawled up and down the aisles of the Sahara’s Congo Room to prove it. And “That,” said Linkletter, “is how I’d act if I were meeting her mother!”

Do you detect herein anything overly prim or straight-laced about Patti Kate’s mother? Do you find her innate niceness a necessarily dull quality? If so, MODERN SCREEN begs to differ.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1954