To daddy With Love—Frank Sinatra

I got stood up by Frank Sinatra. We had a date for three-thirty one afternoon. I was helping Art Linkletter as fashion commentator at a tea party for the American Cancer Fund, but when I noticed that the hour of my date was at hand and the party still wasn’t over, I sneaked out and left Art holding the bag. After rushing home, I got a phone-call from Frank. “I’m terribly sorry,” he said, “but I can’t make it.”

Well, you could have heard me scream two blocks away!

Then he explained. He wasn’t finished with a recording session at NBC, and he had a date in a couple of hours that he just wouldn’t break. And with another girl, yet. What was more humiliating was that this “other woman” was only thirteen years old, and Frank was taking her to her confirmation at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills, and later with five of her friends to dinner at LaRue.

“I can’t stand her up, Hedda,” he pleaded.

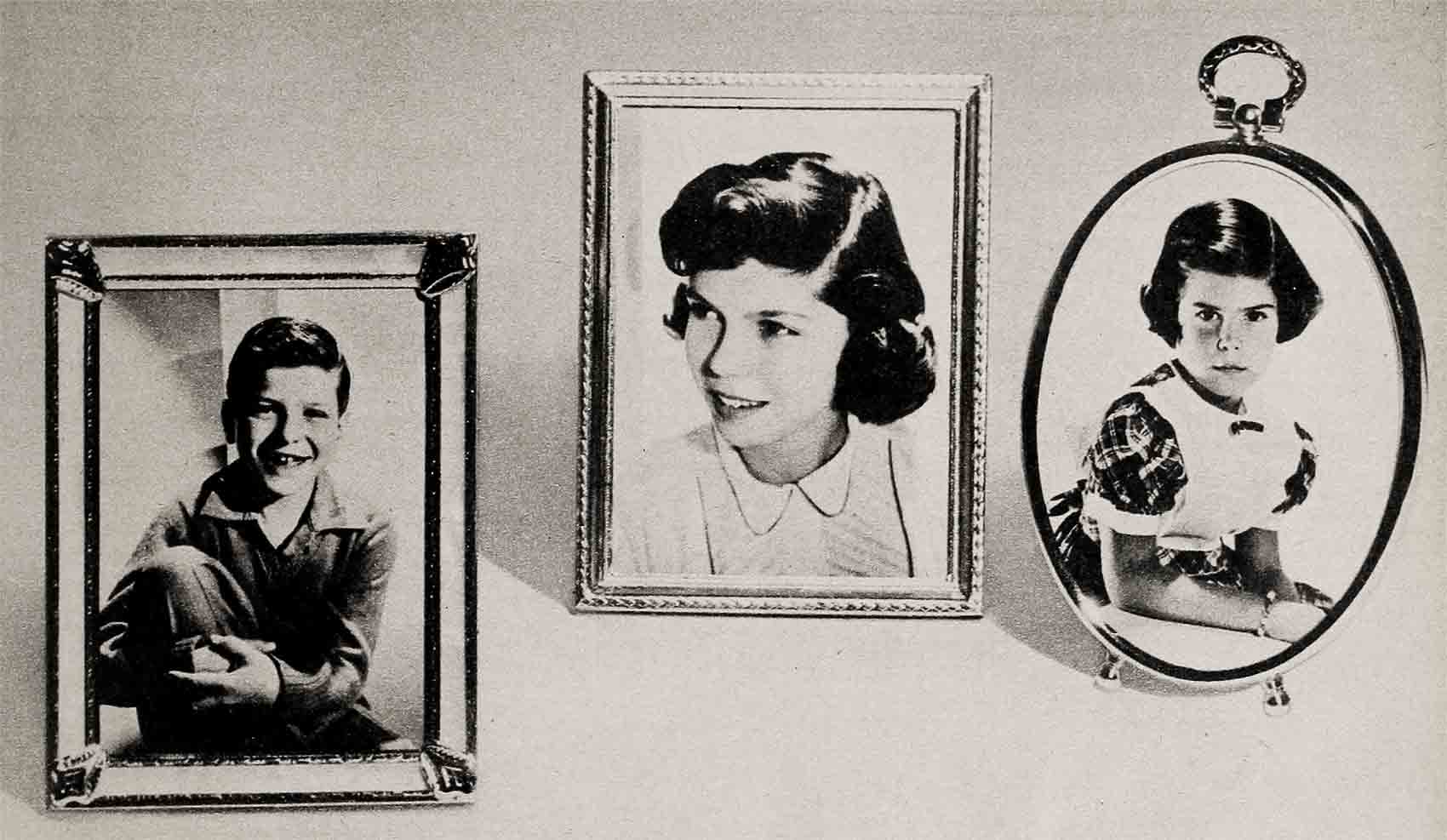

I couldn’t compete with the other woman in his life, because she was Nancy with the laughing face, his oldest daughter. It was through her “pull” that he now owns an Oscar. Here’s the inside story.

His three kids presented him with a St. Genesius Medal (patron saint of actors) with a tiny Oscar in bas relief on the back and this inscription: “Dad, we’ll love you from here to eternity.” In case he didn’t win the award, they wanted him to have their Oscar.

But Nancy had her own idea. She didn’t confide in her brother Frank or her sister Tina, but just before the awards were announced, she slipped her hand into her dad’s and said, “This is from me and Saint Anthony.” It was a Saint Anthony medal.

Well, that did it. With Saint Anthony and Nancy on his side, Frank’s Oscar was in the bag. He later told me: “Saint Anthony is her dearest friend. She seems to get a lot done with him. I sometimes suspect she has a direct wire to him.”

I simmered down about being stood up and made a date with Frank for the following day. He arrived on the dot, but before he came there was a telephone call waiting for him. I said, “You’d better get rid of it because this is going to be a long, tough grilling.”

He returned the call, came into my den, sat down, and said, “Okay, shoot! What’s on your mind?”

Then it was his turn to be amazed.

“I’m not going to ask you a lot of foolish questions about Ava Gardner,” I said. “I’m not even going to ask what your plans are when she returns from Europe; what kind of jewelry you’re buying; or whether you’re house hunting. This story I want is about your children.”

Frank relaxed, and the sigh that emanated from his small frame all but smothered both of us. This was a subject about which he could become eloquent. In fact, he glowed. He lit up like a Roman candle. “Imagine Hopper not wanting to know the intimate details of my life,” he grinned. “Thank you and I’ll never get over it.”

“How did your dinner party with little Nancy come out?” I asked.

“I’ve never heard so much girl talk in my life,” he said. “Nancy looked beautiful at her confirmation. I had ordered baby orchids for her and her friends. They were at each place at the table. I didn’t get to say a word all through dinner. They just yacked away about school and boys—‘he’s a drip,’ somebody else was “even more of a drip.”

“I’ll bet they were too excited to eat,” said I.

“Not on your life,” replied Frank. “They lapped up everything from soup to nuts to ice cream.”

I’d heard many stories about Frank and his kids from our mutual friend, Al Levy. “I know he’s prejudiced,” I told Sinatra, “but are the stories true?”

“That all depends on what he told you.”

“Well, for instance, that when you were singing in Miami and little Nancy was sick, you telephoned her every day.”

“That’s true, but I phone the kids almost every day when I’m away. And when I’m in town, I go by to see them five nights a week. We watch television together and have musical shows, and lately I’ve been helping them with their painting. There’s a new gimmick on the market—portraits of people like Liberace and Bob Hope, with sections of the face numbered to correspond with different colors of paint. I help the kids blend the ‘colors. You’d have had hysterics watching what we did to Hope the other night. He never would have recognized himself.”

This is the only painting Frank has had time for lately. His old friend, the late Perry Charles, got him started painting clowns, but he’s been too busy lately with his career for the hobby.

Al levy had told me that little Frankie is the spitting image of his old man. I questioned Frank.

“He’s so like me it’s frightening. Only a little rounder in the face. If I stand in front of the fireplace with my hands behind my back, he does the same thing. He composes his own music and sings, too.” Frank laughed. “He kills me. When I do a television show, he’ll quote everything I said the next time I see him. He’s very show-wise and talks stage lingo. ‘Now about that joke, Dad,’ he’ll say.

“He loved Anything Goes, the television show I did with Ethel Merman, but he’s quite a critic. The day after the program, he said, ‘Dad, that bit you did dressed in women’s clothes was very funny.’ He thought the chase scene was the best part of the show.

“The kids” favorite TV shows are the comics—Skelton and. Berle. They also watch the cowboys. When it looks as though Bill Boyd is about to kiss the girl, Frankie says, ‘Oh, go on, kiss her. Get it over with and get on with the show.’

“He met Boyd once and has never gotten over it. He didn’t have a word to say to his hero except a polite ‘How do you do?’ That’s the way he is. When he gets really excited he’s perfectly quiet. But an hour or two later, after he has thought it over, he starts yacking. He’ll tell you everything that went on, describe the scene and re-enact the whole event.”

Frank was off to the races on his favorite subject—his son—so I didn’t interrupt. “What I love about Frankie,” he said, “is his great comedy sense and droll humor. He rarely laughs at anything he says, and seldom at anything anybody else says. But when he gets tickled, he falls apart. His eyes water, he breaks up. He laughs inwardly.

“I was having dinner with the children the night before they were to give their annual music recital. I asked Nancy what she was going to play. She replied, ‘The piano concerto.’ I was discussing it with her and didn’t think Frankie was paying any attention. He’s a dreamer, but when you think he’s miles away he’ll come up with something funny and let loose with a line that knocks you right out of your chair.

“Right in the middle of this serious discussion with Nancy, Frankie said, ‘I gotta play that stinking Hungarian Dance. I did it last year and I don’t want to repeat.’

“ ‘What do you want to do?’ I asked, after I’d pulled myself together.

“ ‘I’d like to get up and tell some jokes or something.’

“ ‘One-man jokes?’

“ ‘One-man or two-man jokes.’

“ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘maybe you and I could get some candy-striped suits, straw hats, and tell some two-man jokes.’ We have a routine that breaks Frankie up. I’ll say to him: ‘Have you seen any new one-hundred-dollar bills?’

“And he’ll come back with: ‘Haven’t even seen any old ones.’ He reads his lines like W. C. Fields might have. We have another that Frankie thinks is funny. I ask: ‘Why did you cut holes in the rug?’

“ ‘To see the floor show,’ he answers.

“I really think he wants to be a comic. He likes Red Skelton, and after a Skelton show he’ll talk about Red’s jokes by the hour. He can remember every joke on the show. Good or bad, I don’t know, but he might be a comic—and if he is, he’ll be a good one.”

“What would you like your kids to. be?” I asked.

“I’d like that to come directly from them,” said Sinatra. “I will guide them in whatever they want to do. Frankie seems talented in music. If later he wants to conduct or compose, I’ll guide him, tell him where to go and who to see. But then he may want to be a mathematician. He’s a whiz at figures.”

“And where does he get that talent?”

“Not from me,” said Frank. “He must get that from his mother. She’s very bright at figures.” (Still I didn’t mention Ava.) “I can put numbers together, but when it comes to adding nines, I’m in real trouble.

“Like most kids, Frankie knows all about jet planes and automobiles, too. The other day when I went to see him, he said, ‘Dad, those fins are much too high on your new Cadillac. I like the Nash better.’

“One day when I walked in Frankie was playing the piano. He didn’t know I was there, so I stood outside the door and listened. Finally I walked over to the piano.

“ ‘Oh, hello, Dad,’ he said.

“ ‘How are you, son? What’s that you’re playing?’

“It was something that sounded almost classical which he had composed. We discussed it a minute. Then he said, ‘You know, I’ve been thinking about that new car of yours. I’ve given it a lot of thought. It’s not too good. You know they haven’t had a body change in those cars since 1950.’ When he comes out with something like that, what are you going to do but laugh?”

“You’ve told me about Nancy and Frankie. How about Tina? What’s she like?

“They’re all three a different species,” said Frank. “Nancy’s the practical one, the little mother; Frankie’s a dreamer; and Tina is an explosive hellion. While Nancy and Frank both are rather complacent, Tina is the firecracker and a great flirt. She knows how to work a guy over—she’ll be a heart-breaker some day. She’s just about four feet high, so I was a little surprised when she asked me for one of my pink shirts. ‘What for?’ I asked. She explained that the kids in her class all do fingerpainting, and they use their dads’ shirts with the sleeves cut off as smocks. Well, that figured. Then I asked, ‘Why pink?’

“ ‘Well,’ said Tina, ‘I like to use all the colors that blend well with pink, and if I get paint on the smock it won’t look bad.’ I took her a shirt, and you should see her in it. She all but trips every time she takes a step.

“My clothes are very popular with the girls. Nancy wanted to know if I had a long-sleeved yellow cashmere sweater. I found one and gave it to her. It was pretty horrible on her—came down to her knees. But all the kids wear sloppy-Joes, so she just pushed up the sleeves and liked it.

“Frankie hasn’t asked for any of my clothes so far, but I have a suspicion it won’t be long now. He’s usually content to wear blue dungarees and scuffed shoes, but the other day he said, ‘Why do I always have to wear dark blue or grey suits? Why can’t I ever wear bright colors?’ He dotes on bow ties.”

All the Sinatra children, unlike the offspring of many movie stars, attend public school. That’s the way Frank wants it. He feels they should be able to get along with all types of children, and judging from the number of their friends they seem to do a good job of it.

Frank left his family for the nonce and got onto another subject, about which he yacked just like his kids. “You know, Hedda, I’ve got a wonderful program lined up, and I want to shout about it. After Pink Tights, I’m going to do a musical with Gene Kelly. I’ve talked with Leland Hayward about the part of Ensign Pulver in Mr. Roberts,and to Stanley Kramer about a role in Not As A Stranger. I’ve got so much picture work lined up, I’m giving up nightclubs for the time being. I’m beginning to settle down.”

“I’ve noticed that,” said I. “Success is a great settler, isn’t it? The thing Ive noticed most about you lately is that you don’t fly off the handle like you used to. How do you explain that, please?”

“I’ve got a new system. When anybody needles me, I ignore him and walk away. Things have improved. But—and this is important—I’ll never lose the feeling of hating to have my privacy invaded. We in show business (anybody in the public eye from President Eisenhower on down) are under a magnifying glass. Everything we do is reviewed. I’ve often wondered what kind of a world it would be if every working man’s efforts were reviewed as ours are. If the plumber, say, who came to fix the pipe and didn’t get it quite right got a big review about his error in his trade paper next day. We’d have the most neurotic world you can possibly imagine.

“If someone comes up to me and says, ‘Could I see you for a minute?’ or ‘Could I have a picture of you?’ I’m more than willing to comply. But let somebody snap his fingers and say, ‘Get over there quick!’ That does it! If I did it to them, they’d react the same way I do. There are at least five guys who love to needle me. They know my low boiling point. But since I know who they are and what they’re after, I avoid them or try to smile and keep my temper in check.”

“You’ve got to admit, though, that you’ve got a healthy temper.”

“Sure I’ve got one—who hasn’t? But after the thing is over, I feel twice as bad. You feel awful and think, ‘Geez, I’m sorry that had to happen.’ The thing to do is to see that it doesn’t happen again.”

It was then that I noticed a tiny bald spot on top of his head. “Hey,” I told him, “you’re getting thin on top. I’ve got the very thing for you. I know a man who’s invented something wonderful to grow hair.”

He screamed with laughter. “I know a guy, who shrinks heads so it looks like you’ve got hair.”

I insisted that my friend really had invented such a substance.

“Hedda, if you say so, I’ll use it. It’ll probably work so well I’ll look like a poor man’s John L. Lewis with big bushy eyebrows, too. On the other hand I might wind up wearing a wig if your friend isn’t a good chemist. But say, I think I know where you can contact a guy who’ll sell you the Golden Gate Bridge.”

“All right, you’ll be sorry when you have to wear one of those skull doilies like Bing Crosby.”

Frank got up to take his leave, and I walked him to his car. “You know what?” I said. “Frankie’s right. The fins on your Cadillac are too high. And why did you get a soft top? The way you drive, if you turn over there’s nothing to protect you.”

“Remember me?” he said. “I’m Sinatra, that reformed character. No back talk, no temper, no speeding. I’ve slowed down to a crawl.”

He took off as though the entire Los Angeles police force were after him.

THE END

—BY HEDDA HOPPER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1954

No Comments